|

Project Execution Fundamentals Tracking |

| << Team leader, Project Organization, Organizational structure |

| Organizational Issues and Project Management >> |

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

LECTURE

# 7

2.

Software Development

Fundamentals

Management

Fundamentals

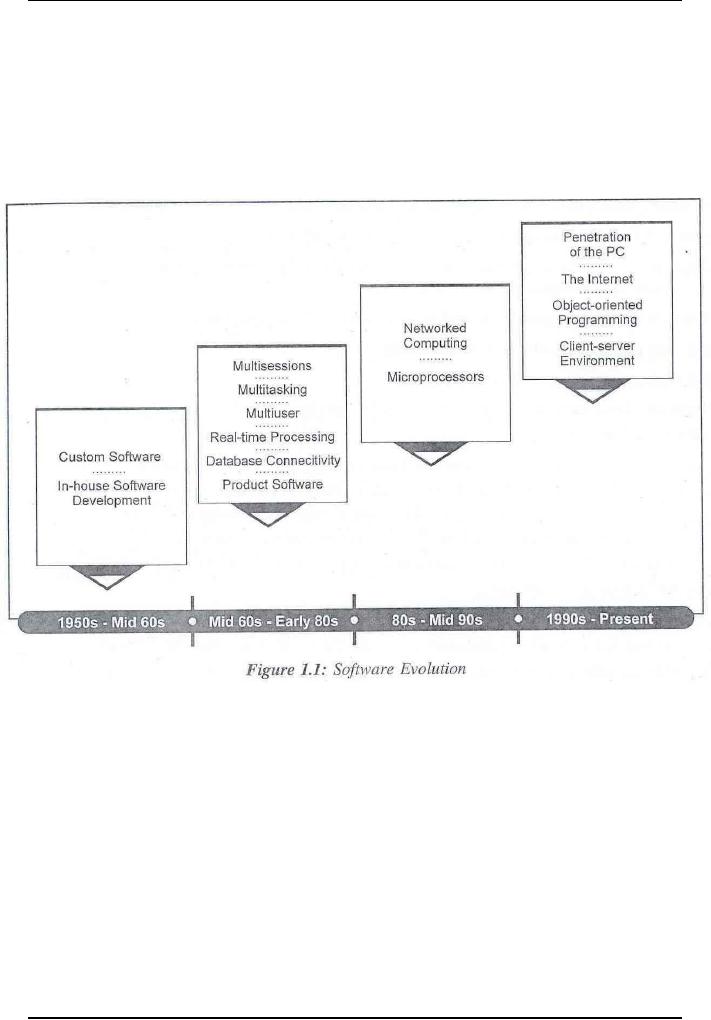

2.1

Evolution

of Software

The

understanding about software and

software development has come a

long

way

from the days of punch cards

and Ada. In the first stage

of computing,

hardware

mattered the most. Computers

themselves were the domains

of the

government,

and most software was developed in

defense-funded labs,

dedicated

to the

advancement of science and technology in

the national

interest.

By the

1950s, large corporations realized

the benefits of using

computers. They

increasingly

started using computers to process and

analyze financial and

production

data. These computers were

huge in size. There was

inadequate

software

available for them. Even

the software that existed

was designed

essentially

to function on a specific hardware

product. The software

was

developed

and maintained by the company

that manufactured the

hardware.

Software

design and documentation existed only in

the developer's head. If

the

developer

left the company, you

would find maintenance to be a

nightmare.

In the

second phase of software

evolution, the corporate and

academic sectors

increasingly

started using computers, and the

perspective about both

software and

software

development began to change. By the

late 1960s and early

1970s,

concepts

such as multi-sessions, multi-user

systems, multiprogramming gained a

foothold.

Soon computers were developed to

collect, process, transform,

and

analyze

data in seconds. The focus

of software development shifted

from custom

software

to product software. Now,

multiple users on multiple

computers could

use

the same software. This

phase of software evolution also saw

the emergence

of

software maintenance activities. These

activities comprised fixing

bugs, and

modifying

the software based on

changes in user requirements.

The

third phase in software

evolution was driven by the widespread

use of

silicon-based

microprocessors, which further led to

the development of

high-

speed

computers, networked computers, and

digital communication. Although,

all

the

advancement in software and hardware was

still largely restricted to

enterprise

applications

manufacturers had begun to see

the application of the

microprocessor

in

something as mundane as ovens to

the robots used in car

plants.

The

fourth, and current, phase of

software evolution began in

the early 1990s.

This

phase saw the growth of

client-server environment, parallel

computing,

distributed

computing, network computing, and

object-oriented programming.

59

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

This

phase also witnessed the

growing popularity of personal

computer (PC).

60

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

was

prevalent in the early

stages of software evolution hampered

the application

of

systematic processes. This

conflict referred to as the

software crisis. Some

of

the

reasons to which you can

attribute the software

crisis include:

Software

developers used-multiple programming

languages.

Software

developers used multiple

variations of standard programming

languages.

Most of

the requirements were

complex with regard to the

existing

capabilities,

Users,

who had little or no experience of

developing or even

using

software,

formulated requirements.

Software

developers poorly mapped

requirements to the actual

product.

Software

developed had low

interoperability.

Software

maintenance was costly.

Hardware

developed at a faster rate than

software (better

hardware

requires

better software to operate

it).

During

the period of software

crisis, you will find that

software that was

produced

was

generally over budgeted, under

scheduled, and of poor quality.

The

immediate

knee-jerk response to these

problems was software

maintenance,

which

began to consume huge resources.

During this period,

maintaining software

was

adopted as a short-term solution due to

the costs involved in fixing

software

regularly.

This often resulted in the

original software design approach getting

lost

due to

the lack of

documentation.

In

contrast, the situation in

the present times has changed to a

large extent.

Software

costs have risen, although

hardware is purchased easily off

the shelf.

Now,

the primary concerns

regarding software projects

are project delays,

high

costs, and a

large number of errors in

the finished product.

2.2

Project

Execution Fundamentals

Tracking

For

the project manager, it is essential to be

constantly informed of the

true status

of the

project. This is achieved by

assuring the regular flow of

accurate

information

from the development teams.

Many of the methods of

acquiring

information

are not objective and rely

on the accuracy of the

reports provided by

the

project developers themselves.

They include:

Periodic

written status reports

Verbal

reports

Status

meetings

Product

demonstrations (demos)

Product

demonstrations are particularly

subjective, because they demonstrate

only

what

the developer wishes to be

seen. The project manager

needs objective

61

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

information.

Such information can often be

acquired from reports

produced by

support

groups, such as:

Quality

assurance reports

Independent

test reports

Although

reports and meetings are indeed

useful sources of information,

nothing

can replace

direct contact between the

project manager and the development

staff.

Frequent

informal talks with the

developers are excellent

sources of information,

especially

when held in an informal atmosphere

(and not in the project

manager's

office).

The

project manager must keep on

constant guard against an error

commonly

referred

to as the '90/50 syndrome',

which states that, 'it

takes 50 percent of

the

time to

complete 90 percent of the

work, and an additional 50 percent of

the time

to

complete the remaining 10

percent of the work'. This

means that project

developers

will begin to boast quite

early that they have

'almost finished'

their

tasks.

Unfortunately, there is a great

difference between 'almost

finished' and

`finished'.

Finishing

a task -writing documentation, and

polishing off the last

few problems,

often

takes longer than developers

anticipate. This is because

these activities

produce

very few visible results,

and developers tend (wrongly) to

associate work

with

results. Therefore, managers can

obtain more information from

developers

by asking

them how long they estimate

it will take to finish, and not how

much of

their

work has been

completed.

�

Status

reports

Status

reports should be required

from every member of the

development team,

without

exception. The reports

should be submitted periodically,

usually weekly

or

bi-weekly, and should contain at least

the following three sections

(see Fig.

5.8):

1.

Activities

during the report

period

Each

subsection within this

section describes a major

activity during the

report

period.

The description of each

activity should span two to

three lines.

Activities

should be

linked to the project task

list or work breakdown

structure (WBS) (see

Chapter

10 for a description of the

WBS).

2.

Planned

activities for the next report

period

Each

subsection within this

section describes a major

activity planned for the

next

report

period. The description of

each activity should span

one to two lines.

3.

Problems

62

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Each

subsection within this

section describes a major

problem that either

occurred

during

the report period, or that

was reported previously and has

not yet been

resolved.

This means that problems

will be repeatedly reported until

they are

resolved.

In particular, this section

must explain why this

report's Section 1

does

not

correspond to the previous

report's Section 2.

All

reports should also

contain:

1. Date of

report

2. Report

period (e.g. 3 July to 10

July 1992)

3. Name

of report (e.g. Communications team

status report)

4. Name

of person submitting the

report

The

preparation of a periodic status report

should take about 20 minutes,

but not

longer

than 30 minutes. Developers

should submit their status

reports to their

team leader.

The team leader then combines

the reports of the team into

a single

status

report, while maintaining

the same report structure.

This activity should

take the

team leader about 30 minutes, but

not longer than 45 minutes

(this is

easily

done when the reports are

prepared and submitted by electronic

mail).

Each team leader

submits the team status report to

the project manager.

The

individual

status reports need not be

submitted; these should be

filed and

submitted

to the project manager only on

request.

63

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

From:

John Doe, Team leader

To:

Frank Smith, Project

Manager

Date: 15

June 1993

User

interface team: Weekly status

report

for

the period 5-12 June

1993

1.

Activities during the report

period:

1.1

The design of the user help

screens (activity 3.12.6) was

completed on schedule.

The

design specs were submitted to

configuration control.

1.2

Coding of the command pass

through modules (activity

group 5.12) continues, and

is

currently

behind schedule by about 1

week.

2.

Activities planned for next

week:

2.1

Coding of the command pass

through modules (activity

group 5.12) will be

completed,

and unit tests will be started.

2.2

Two members of the team (Ed and Joan)

will attend a two day course on

the

Programmer's

interface to the new user

interface package. This is an

unscheduled

activity

that was approved at the

last project meeting. This

will not delay the

schedule,

due to the early completion of

the command pass through

modules (see

Section

1.2 above).

3.

Problems:

3.1

The user interface package we

originally planned to use was

found to be inadequate

for

the project. Two team members will

study the new proposed

package (sec Section

2.2

above).

If the new package is also

found to be unsuitable, then

this will severely

impact

our

development schedule.

3.2

One of our team members (Jack Brown)

has been using an old

VTI00 terminal

instead of a

workstation for the past

two weeks, due to the acute shortage

of

workstations.

This is the reason why

Jack's task 5.12 was not

completed this week,

as

scheduled.

Figure

5.8: Example

of a weekly status report

The

project manager also receives status reports

from other project

support

personnel

such as the project systems

engineer or the deputy

project manager. The

project

manager then prepares the

project status report by combining

the

individual

reports received into a

single three-part report.

The project status

report

is then

submitted to top

management.

64

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Project

status reports are not

necessarily submitted at the

same frequency as

internal

project status reports. Project

reports may be submitted

bi-weekly or

monthly.

�

Project

status meetings

Project

status meetings should be held

periodically, usually once a week. A

good

time

for status meetings is either at

the end of the last day of

the week, or at the

beginning

of the first day of the

week. Status meetings also contribute to

the

atmosphere of

order and control within the

project, and should be held

regularly,

at a

fixed time. Participants who

cannot participate in the

project status meeting

may,

with the project manager's

approval, delegate participation to

another

member of

their team.

The

project manager prepares for

the status meeting by reviewing

the status

reports

submitted by the key project

members (particularly scrutinizing

the

problem

section). Therefore the status

reports should be submitted at least

two to

three

hours before the status

meeting. Project status meetings

are attended by the

key

project members. The meeting begins

with a report of project

activities and

general

issues by the project manager.

Then each participant should

be given

about

five to ten minutes to

report on the activity of

his or her team or area

of

responsibility.

The discussion of problems

should not be restricted to

the person

reporting

the problem and the project

manager. All problems may be addressed

by

all

participants, with possible assistance

offered between team leaders,

thus

making

their experience available

throughout the project. It is

not the project

manager's

role to provide solutions to

the problems, but rather to

guide the team

members

toward solutions.

Solutions

should be worked out

whenever possible during the status

meeting. Any

problem

not resolved within five

minutes should be postponed for

discussion by

the

relevant parties after the status

meeting. The proceedings of all

project status

meetings

must be recorded. Verbatim minutes

are not required, though

the

following

items should appear in the

record:

1. Date of

meeting

2. Name

of meeting

3.

Present (list of

participants)

4. Absent

(list of absent invited

participants)

5. Action

items (name, action, and

date for completion)

6. Major

decisions and items discussed

The

record of the project status

meeting should be typed and

distributed as soon

as possible,

but no later than by the end

of the day. This is

particularly important

when

there are action items to be

completed on the same day.

When the project is

sufficiently

large to justify a secretary,

then the record will be

taken and typed by

65

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

the

secretary. In smaller projects,

the project manager can rotate

this task each

week

between the

participants.

2.3

Software

Project Management

Framework

You all

know that a project is much

more than a collection of

methodologies,

tasks, resources, and

reviews. A project is a synchronized

event where there is

perfect

harmony and understanding between

the participants. The

participants are

equipped

with the essential skills of

planning, cooperating, helping,

and

communicating.

However, the most important

activity here is to orchestrate

the

movement

of the participants. The

onus lies with the

project manager to

synchronize

the activities of the

project to result in a perfect

presentation.

Although

each project manager has a

unique style of functioning,

there are some

fundamental

approaches that guide a

project manager. These approaches

are

traditional

project management concepts and software

engineering concepts. To

understand

software projects and their

dynamics, you must be aware of

the

environment

in which a software project is

executed. This further

requires an

understanding

of the larger framework of

software project

management.

In this

chapter, you will learn to,

build a connection between

traditional project

management concepts

and software engineering concepts. Both

traditional and

software

projects share the same

methodologies, techniques, and

processes.

However,

managing software projects

requires a distinct approach. In

this,

chapter,

you will learn to apply

traditional project management principles

to

software

projects. Further, you will

learn about the

responsibilities of a software

project

manager. You will also learn about the

phases in a software project

and

the

activities within each

phase. Finally, the chapter

will provide you an

overview

of the

problems that affect a

software project and the

myths prevalent about

software

project management.

2.4

Software

Development Life Cycle (SDLC)

The

development of a software project

consists of many activities spread

across

multiple

phases. Dividing a software

project into phases helps

you in managing

the

complexities and uncertainties involved

in the software

project.

2.5

Phases

of a Software project

Each

phase represents the

development of either a part of

the software product

or

something

associated with the software

project, such as user manual or

testing.

Each

phase is composed of various

activities. You can consider a phase

complete

when

all activities are

complete.

66

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

A phase

is named according to the primary

deliverable set that is

achieved at the

end of

that phase. For example, if

the requirements document is

required as the

output,

the phase is called the

requirements phase. Similarly,

most software

projects

have phases for analysis,

design, construction, implementation,

and

testing.

A typical

software project includes

the following phases:

Software

requirement analysis

phase

Software

Design Phase

Software

Planning Phase

Software

construction phase

Software

testing phase

Software

acceptance and maintenance

phase

2.6

SDLC

Models

Different

organizations have different

ways of assessing and arranging

the phases

in a

project. These are called process

models. Process

models define how a

software

life cycle actually works.

They provide you with a

framework to plan

and

execute the various phases

in the project. Typically,

project life cycles

display

the

following characteristics:

�

The

level of cost and effort required in a

software project life cycle

is small to

begin

with but grows larger

towards the end of the

project. This happens

because

the phases such as software

construction and implementation,

which

come at

later stages in a software

project, require more

resources than the

initial

phases of the

project.

�

At the

start of the SDLC, external

entities, such as the

customer and the

organization,

play an important role with

regard to their effect on

the

requirements.

However, towards the end of

the software project as the

cost

and

effort required to implement

changes rise, the requests

for change in

requirements

decreases.

�

The

uncertainty faced by the software

project is highest at the

beginning of the

SDLC.

Their level decreases as the

project progresses.

There

are a few standard software

process models that you can

use, with some

customization.

Some standard process models

are given below:

�

The

Waterfall

model:

This is the traditional life

cycle model. It assumes

that

all

phases in a software project

are carried out sequentially

and that each

phase is

completed before the next is

taken up.

�

The

Prototyping

Model: A

model that works on an

iterative cycle of

gathering

customer

requirements, producing a prototype

based on the

requirement

specifications,

and getting the prototype

validated by the customer.

Each

67

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

iteration

of the life cycle builds on

the prototype produced in

the previous

iteration.

�

The

Incremental

Model:

The Incremental model is an

example of an

evolutionary

life cycle model. It

combines the linear nature

of the Waterfall

model and

the iterative nature of the

Prototyping model. The

Incremental

model

divided the development life

cycle into multiple linear

sequences, each

of which

produces an increment of the final

software product. In this

model,

the

software product is developed in

builds. A build is defined as a

self-

contained

unit of the development

activity. The entire

development cycle is

planned

for a specific number of

logical builds, each having

a specific set of

features.

�

The

Spiral

model:

Another evolutionary life

cycle model that combines

the

linear

nature of the Waterfall

model and the iterative

nature of the

Prototyping

model.

The project life cycle is

divided into phases, and

each phase is

executed

in all of the iteration of

the Spiral Model.

68

Table of Contents:

- Introduction & Fundamentals

- Goals of Project management

- Project Dimensions, Software Development Lifecycle

- Cost Management, Project vs. Program Management, Project Success

- Project Management’s nine Knowledge Areas

- Team leader, Project Organization, Organizational structure

- Project Execution Fundamentals Tracking

- Organizational Issues and Project Management

- Managing Processes: Project Plan, Managing Quality, Project Execution, Project Initiation

- Project Execution: Product Implementation, Project Closedown

- Problems in Software Projects, Process- related Problems

- Product-related Problems, Technology-related problems

- Requirements Management, Requirements analysis

- Requirements Elicitation for Software

- The Software Requirements Specification

- Attributes of Software Design, Key Features of Design

- Software Configuration Management Vs Software Maintenance

- Quality Assurance Management, Quality Factors

- Software Quality Assurance Activities

- Software Process, PM Process Groups, Links, PM Phase interactions

- Initiating Process: Inputs, Outputs, Tools and Techniques

- Planning Process Tasks, Executing Process Tasks, Controlling Process Tasks

- Project Planning Objectives, Primary Planning Steps

- Tools and Techniques for SDP, Outputs from SDP, SDP Execution

- PLANNING: Elements of SDP

- Life cycle Models: Spiral Model, Statement of Requirement, Data Item Descriptions

- Organizational Systems

- ORGANIZATIONAL PLANNING, Organizational Management Tools

- Estimation - Concepts

- Decomposition Techniques, Estimation – Tools

- Estimation – Tools

- Work Breakdown Structure

- WBS- A Mandatory Management Tool

- Characteristics of a High-Quality WBS

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- WBS- Major Steps, WBS Implementation, high level WBS tasks

- Schedule: Scheduling Fundamentals

- Scheduling Tools: GANTT CHARTS, PERT, CPM

- Risk and Change Management: Risk Management Concepts

- Risk & Change Management Concepts

- Risk Management Process

- Quality Concept, Producing quality software, Quality Control

- Managing Tasks in Microsoft Project 2000

- Commissioning & Migration