|

Quality Concept, Producing quality software, Quality Control |

| << Risk Management Process |

| Managing Tasks in Microsoft Project 2000 >> |

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

LECTURE

# 42

10.Quality

10.1

Quality

Concept

What

is it? It's

not enough to talk the

talk by saying that soft

ware

quality is

important,

you have to (1) explicitly

define what is meant when

you say 'software

quality,

(2) create

a

set of

activities

that will help ensure that

every software

engineering

Work product exhibits high

quality, (3) perform quality

assurance

activities

on every software project,

(4) use metrics to develop

strategies to

improving

your software process and as a

consequence the quality of.

the

end

product.

Who

does it? Everyone

involved in the software

engineering process is

responsible

for quality.

Why

is it important? You can do it

right, or

you can

do it over again. If a

software

team stresses quality in all

software engineering activities, it

reduces the

amount of

rework that it must do that

results in lower costs, and more

importantly,

improved

time-to-market.

What

are the steps? Before

software quality assurance

activities can be initiated,

it is

important to define 'software

quality' at a number of different

levels of

abstraction,

Once you understand what

quality is, a software team

must identify a

set of

SQA activities that will

filter errors out of work

products before they

are

passed

on.

What

is the work product? A

Software Quality Assurance

Plan is created to

define a

software team's SQA

strategy. During analysis, design, and

code

generation,

the primary SQA work

product is the formal

technical review

summary

report. During testing, test

plans and procedures are produced.

Other

work

products associated with

process improvement may also be

generated.

How

do I ensure that I've done

it right? Find

errors before they

become

defects!

That is, work to improve

your defect removal

efficiency, thereby

reducing

the amount of rework that

your software team has to

perform.

SQA

encompasses:

(1) A

quality management approach

(2)

Effective software engineering

technology (methods and

tools)

(3)

Formal technical reviews

that are applied throughout

the software process

(4) A

multi-tiered testing

strategy

356

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

(5)

Control of software documentation and

the changes made to

it

(6) A

procedure to ensure compliance with

software development

standards

(when

applicable)

(7)

Measurement and reporting

mechanisms.

Software

quality is defined as conformance to

explicitly stated functional

and

performance

requirements, documents, and standards.

The factors that

affect

software

quality are a complex

combination of conditions that can be

measured

based on

data, such as audit-ability,

completeness, consistency, error

tolerance,

and

expandability.1n addition, this

data includes hardware

independence,

software

system independence, modularity,

security, and simplicity.

Software

quality assurance is a planned and

systematic approach necessary to

ensure

the quality of a software

product. Software reviews

filter the product of

all

errors.

Software reviews can be conducted at

all stages in the DLC of a

software

product,

such as analysis, design, and

coding.

Testing

is an important element of SQA

activity. There are various

testing tools to

automate

testing process. The SQA

plan is used as the template

for all SQA

activities

planned for a software

project and includes details of

the SQA activities

to be

performed during project

execution.

SCM is

used to establish and maintain

integrity of software items and ensure

that

they can

be traced easily. SCM helps

define a library structure

for storage and

retrieval

of software items. SCM helps

assess the impact of a

recommended

change and make

decisions depending on the costs and

benefits. SCM needs to

be

performed

at all phases in the DLC of

a software project.

The

various SCM activities are

identifying changes, controlling

changes,

controlling

versions, implementing changes, and

communicating changes. These

activities

are independent of the

supervision of the project or

the product

manager.

This is to ensure objectivity in SCM.

The scope of SCM is not

limited

by code

and includes requirements, design,

database structures, test plans,

and

documentation.

SCM procedures vary with the

project.

10.2

Producing

quality software

As we

have seen, one of the main

problems in producing quality

software is the

difficulty

in determining the degree of

quality within the software.

As there is no

single

widely accepted definition

for quality, and because

different people

perceive

quality in different ways,

both the developer and the

customer must

reach agreement on

metrics for quality' (this

is discussed in more detail

later). The

method of

measuring quality may differ

for different

projects.

357

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

This

problem is discussed in a paper by

Wesselius and Ververs (1990), in

which

they

conclude that complete

objectivity in quality assessment

cannot be achieved.

They

identify three distinct

components of quality:

An

objectively assessable

component

A

subjectively assessable

component

A

non-assessable component

The

quality of a product is objectively

assessable when the

characteristics of the

product,

as stated in the requirements

specification, can be identified.

The

quality of a product is subjectively

assessable when the

characteristics of the

product

comply with the customer's

expectations.

The

quality of a product is non-assessable

when it behaves according to

our

expectations

in situations that have not

been foreseen.

Wesselius

and Ververs suggest that,

for the quality of a

software product to be

assessable,

as many characteristics as possible

should be moved from

the

subjective

and non-assessable components to the

assessable component.

Essentially,

this means that the

requirements specification must

describe as many

measurable

characteristics of the product as

possible.

Experience

supports Wesselius and Ververs'

conclusions. Badly

defined

requirements

are always a source of dispute

between developer and

customer.

Well-defined,

detailed and measurable requirements

minimize disputes and

disagreements

when the development of the

product is complete.

However,

many development methods

have a prolonged interval

between the

specification

of requirements and the delivery of

the product (refer to

Chapter 4

for a

discussion of the software

development cycle). The

determination of quality

should

not be postponed until development is

complete. Effective software

quality

control

requires frequent assessments

throughout the development

cycle. Thus,

effective

quality control coupled with

a good requirements specification

will

clearly

increase the quality of the

final product.

10.3

Quality

Control

Variation

control may be equated to

quality control. But how do

we achieve

quality

control? Quality control

involves the series of

inspections, reviews, and

tests

used throughout the software

process to ensure each work

product meets the

requirements

placed upon it.

Quality

control includes a feedback loop to

the process that created

the work

product.

The combination of measurement and feedback

allows us to tune the

358

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

process

when the work products

created fail to meet their

specifications. This

approach

views quality control as

part of the manufacturing

process.

Quality

control activities may be fully

automated, entirely manual, or

a

combination

of automated tools and human

interaction. A key concept of

quality

control

is that all work products

have defined; measurable specifications

to which

we may

compare the output of each

process. The feedback loop is essential

to

minimize

the defects produced.

10.4

Quality

Control Myths

The

establishment of effective quality

control frequently encounters

various

misconceptions

and myths, the most common

of which is related to the

cost

effectiveness

of quality control. Cobb and Mills

(1990) list several of these

myths,

and

suggest methods of combating

them. Two of the more

prevalent myths

identified

by Cobb and Mills are described

below.

Myth:

Quality costs money. This is

one of the most common myths

(not only in

software

development). In fact, quality in

software usually saves

money. Poor

quality

breeds failure. There is a

positive correlation between

failures and cost in

that it

is more expensive to remove

execution failures designed

into software than

to design

software to exclude execution

failures.

Myth:

Software failures are unavoidable.

This is

one of the worst

myths

because

the statement is partly

true, and is therefore often

used as an excuse to

justify

poor quality software. The

claim that `there is always

another bug' should

never be

a parameter in the design or implementation of

software.

As these

myths lose ground in modern

approaches to software development,

the

demand

for suitable quality control

standards and procedures increases. The

IEEE

issued

their first standard for

software quality assurance

plans in 1984 (IEEE

.1984),

followed by a detailed guide to

support the standard, issued in

1986. The

US

Department of Defense issued a separate

standard 2168 for defense systems

software

quality programs (DOD

1988b), which forms a

companion to the

famous

US DOD

standard 2167A (DOD 1988a) for

defense systems software

development.

The European ISO standard

9000-3, of 1990 (ISO 1990)

gives a

broader

meaning to the term quality

assurance and covers configuration

control

too.

10.5

Resources

for quality

control

When

the SQA mandate includes

configuration control activities,

the required

resources

will also include those required for

configuration control. Merging

SQA

and

configuration control is not

uncommon, and can eliminate some

duplication

of assignments and

activities. Two alternative

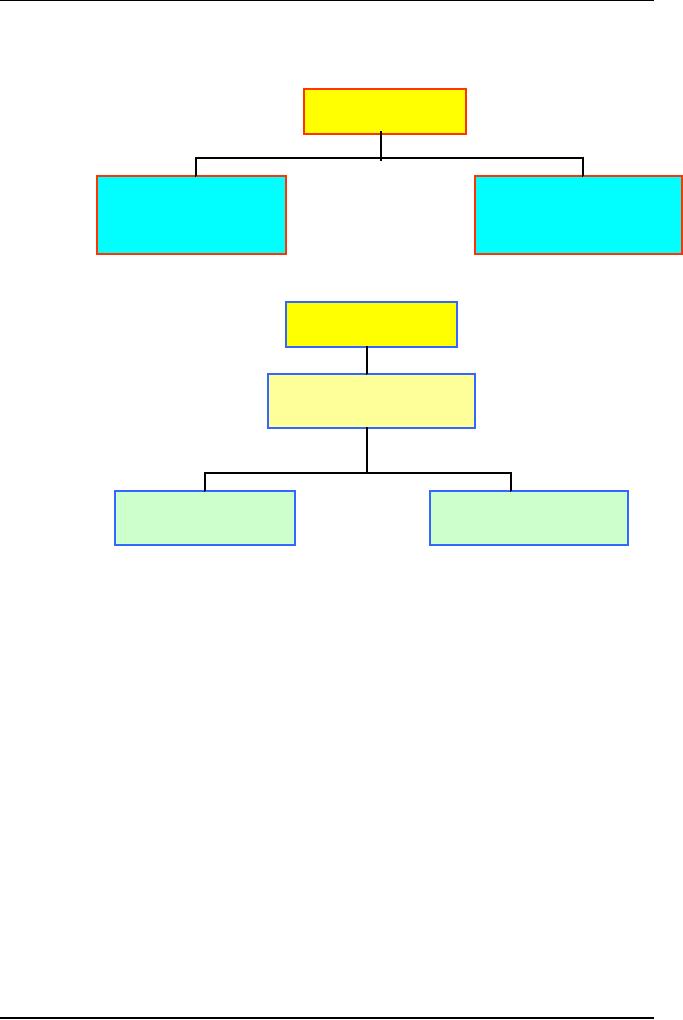

organizational charts are

shown in

359

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Fig.

8.5. Note that for

small projects, merging the

two groups may mean

simply

assigning

both responsibilities to the

same person.

Though

many tools are common to

quality control and configuration

control, few

tools

are specifically designed

for quality control. The

following are some of

the

general

support tools that can be

useful in supporting SQA

activities:

�

Documentation

utilities

�

Software

design tools

�

Debugging

aids

�

Structured

preprocessors

�

File

comparators

�

Structure

analyzers

�

Standards

auditors

�

Simulators

�

Execution

analyzers

�

Performance

monitors

�

Statistical

analysis packages

�

Integrated

CASE tools

�

Test

drivers

�

Test

case generators

These

tools support quality

control in all phases of

software development.

Documentation

aids can provide partially

automatic document writers,

spelling

checkers and

thesauruses etc. Structured

preprocessors (such as the UNIX

utility

lint)

are

useful both to standardize code

listings. And to provide

additional

compile-time

warnings that compilers

often overlook. Early

warnings regarding

possible

execution time problems can be

provided by simulators, execution

time

analyzers

and performance monitors. Substantial

software system testing

can

often be

performed automatically by test suite

generators and automatic test

executors.

All SQA

tools to be used during

software development should be

identified and

described

in the SQA plan. This

plan includes a description of

all required quality

assurance

resources and details of how

they will be applied. Thus, at

the start of

the

project SQA resources can be budgeted and

procured as part of the

required

project

development resources.

360

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

(a)

Project

manager

Configuration

Software

quality

control

control

CC

manage

OC

manager

(b)

Project

manager

Software

quality

assurance

SQA

Configuration

Software

quality

control

control

10.6

Quality

Assurance

Quality

assurance consists of

the auditing and reporting

functions of

management.

The goal of quality

assurance is to provide management with

the

data

necessary to I be informed about

product quality, thereby

gaining insight and

confidence

that product quality is

meeting its goals. Of course, if

the data

provided

through quality assurance

identify problems, it is

management's

responsibility

to address the problems, and

apply the necessary

resources to

resolve

quality issues.

Software

Quality Assurance

Even

the most jaded software

developers will agree that

high-quality software is

an

important goal. But how do

we define quality? A wag once

said, 'Every

program

does something right, it

just may not be the

thing that we want it to

do.'

361

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Many

definitions of software quality

have been proposed in the

literature. For our

purposes,

software

quality is

defined as:

Conformance

to explicitly stated functional and

performance requirements,

explicitly

documented development standards, and

implicit characteristics

that

are

expected of all professionally

developed software.

There is

little question that this

definition could be modified or

extended. In fact,

a

definitive definition of software

quality could be debated

endlessly. For the

purposes

of this book, the definition

serves to emphasize three important

points:

1.

Software requirements are

the foundation from which

quality is measured.

Lack of

conformance to requirements is lack of

quality.

2.

Specified standards define a

set of development criteria

that guide the

manner

in which

software is engineered. If the criteria

are not followed, lack

of

quality

will almost surely

result.

3. A set

of implicit requirements often

goes unmentioned (e.g., the

desire for

ease of

use and good maintainability). If

software conforms to its

explicit

requirements

but fails to meet implicit

requirements, software quality

is

suspect.

Background

Issues

Quality

assurance is an essential activity for

any business that produces

products

to be

used by others. Prior to the

twentieth century, quality

assurance was the sole

responsibility

of the craftsperson who

built a product. The first

formal quality

assurance and

control function was introduced at

Bell Labs in 1916 and spread

rapidly

throughout the manufacturing

world. During the 1940s,

more formal

approaches

to quality control were

suggested. These relied on measurement

and

continuous

process improvement as key

elements of quality

management.

Today,

every company has mechanisms to ensure

quality in its products. In

fact,

explicit

statements of a company's concern for

quality have become a

marketing

ploy

during the past few

decades.

The

history of quality assurance in

software development parallels

the history of

quality

in hardware manufacturing. During

the early days of computing

(1950s

and 1960s),

quality was the sole responsibility of

the programmer. Standards

for

quality

assurance for software were

introduced in military contract

software

development

during the 1970s and have

spread rapidly into software

development

in the

commercial world

[IEE94].

362

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Extending

the definition presented

earlier, software quality

assurance is a planned

and

systematic pattern of actions

[SCH98] that are required to

ensure high quality

in

software.

The

scope of quality assurance

responsibility might best be

characterized by

paraphrasing a

once-popular automobile

commercial:

Quality

is Job # 1'. The

implication for software is

that many different

constituencies

have software quality

assurance responsibility-software

engineers,

project

managers, customers, salespeople, and the

individuals who serve within

an

SQA

group.

The

SQA group serves as the

customer's in-house representative.

That is, the

people

who perform SQA must

look at the software from

the customer's point

of

view. Has

software development been

conducted according to

pre-established

standards?

Have the technical

disciplines properly performed

their roles as part

of

the

SQA activity? The SQA

group attempts to answer

these and

other questions to

ensure

that software quality is

maintained.

SQA

Activities

Software

quality assurance is composed of a

variety of tasks associated

with two

different

constituencies-the software engineers who

do technical work and an

SQA

group that has

responsibility for quality

assurance planning,

oversight,

record

keeping, analysis, and reporting. 'If

Software engineers address quality

and

perform

quality assurance and quality

control activities by applying

solid

technical

methods and measures, conducting

formal technical reviews,

and

performing

well-planned software

testing.

The

charter of the SQA group is

to assist the software team in

achieving a high-

quality

end product. The Software

Engineering Institute [PAU93]

recommends a

set of

SQA activities that address

quality assurance planning,

oversight, record

keeping,

analysis, and reporting.

These

activities are performed (or

facilitated) by an independent SQA

group that:

1. Prepares

SQA plan for a

project

The

plan is developed during

project planning and is reviewed by

all

interested

parties. Quality assurance activities

performed by the

software

engineering

team and the SQA group are

governed by the plan. The

plan

identifies

�

evaluations

to be performed

�

audits

and reviews to be performed

�

standards

that are applicable to the

project

363

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

�

procedures

for error reporting and

tracking

�

documents

to be produced by the SQA

group

�

amount of

feedback provided to the software

project team

2.

Participates in the development of the project's

software process

description

The

software team selects a process

for the work to be

performed. The SQA

group

reviews the process

description for compliance

with organizational

policy,

internal software standards, externally

imposed standards (e.g.,

ISO-

900 I), and

other parts of the software

project plan.

3.

Reviews software engineering activities to

verify compliance with

the

defined software

process. The

SQA group identifies,

documents, and tracks

deviations

from the process and

verifies that corrections

have been made.

4.

Audits designated software work

products to verify compliance

with

those

defined as part of the software process.

The

SQA group reviews

selected

work products; identifies,

documents, and tracks deviations;

verifies

that

corrections have been made; and

periodically reports the

results of its

work to

the project manager.

5.

Ensures that deviations in software

work and work products

are

documented

and handled according to a documented

procedure.

Deviations

may be encountered in the

project plan, process

description, -

applicable

standards, or technical work

products.

6.

Records any noncompliance and reports to

senior management.

Noncompliance

items are tracked until

they are resolved.

In

addition to these activities,

the SQA group coordinates

the control and

management of change

and helps to collect and analyze

software metrics.

10.7

SQA

Plan

The

SQA plan serves as the

template for SQA activities

planned for each

software

project.

The SQA group and the

project team develop the SQA

plan. The initial

two

sections of the plan describe

the purpose and references of the SQA

plan. The

next

section records details of the

roles and responsibilities for

maintaining

software

product quality.

The

Documentation section of the

SQA plan describes each of

the work products

produced

during the software process.

This section defines the

minimum set of

work

products that are acceptable

to achieve high quality. The

Documentation

section

consists of:

364

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Project

document such as project

plan, requirements document, test

cases, test

reports,

user manual, and administrative

manuals

Models

such as ERDs, class

hierarchies

Technical

document such as specifications, test

plans

User

document such as help

files

All

applicable standards to be used in

the project are listed in

the Standards and

Guidelines

section of the SQA plan.

The standards and practices applied

are the

document

standards, coding standards, and review

guidelines.

Example

of the contents of a software quality

assurance plan

1.

Software quality assurance organization

and resources

Organization

structure.

Personnel

skill level and

qualifications

Resources

2.

SQA standards, procedures, policies and

guidelines

3.

SQA documentation requirements

List of

all documentation subject to

quality control

Description

of method of evaluation and

approval

4.

SQA software requirements

Evaluation

and approval of software

Description

of method of evaluation

Evaluation

of the software development

process

Evaluation

of reused software

Evaluation

of non-deliverable software

5.

Evaluation of storage, handling and

delivery

Project

documents

Software

Data

files

6.

Reviews and audits

7.

Software configuration management (when

not addressed in

a

separate document)

8.

Problem reporting and corrective

action

9.

Evaluation of test

procedures

10.

Tools techniques and

methodologies

11.

Quality control of subcontractors,

vendors and suppliers

12.

Additional control

Miscellaneous

control procedures

Project

specific control

13.

SQA reporting, records and

documentation.

Status

reporting procedures

Maintenance

365

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

Storage

and security

Retention

period

10.8

Software

quality metrics

Much

attention has been devoted

to questions associated with

the measurement of

quality.

How do we determine the

extent to which a software

product contains this

vague

attribute called quality?

When is the quality of a

software product high

and

when is

it low?

One of

the more recent developments

in quality assurance (not

only for software)

is the

realization that quality is

not a binary attribute that

either exists or does

not

exist.

Kaposi and Myers (1990), in a

paper on measurement-based quality

assurance,

have stated their belief

that 'the quality assurance

of products and

processes

of software engineering must

be based on measurement 7. The

earlier

the

measurement of quality begins, the

earlier problems will be located.

Cohen et

al.

(1986),

in addressing the cost of removing

errors during the early

phases of

software

development, proclaim the

existence of the famous exponential

law8.

366

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

The

quality of two products can be compared,

and it is perfectly acceptable to

claim

that the quality of one

product is greater than the

quality of another. It is

also

acceptable to measure quality and

deduce the extent of expected

faults based

on the

measured result.

The

set of measurable values associated

with the quality of a

product is referred to

as the

product's quality metrics.

Software quality metrics can be

used to determine

the

extent to which a software

product meets its

requirements. The use of

quality

metrics

increases the objectivity of

the evaluation of product

quality. Human

evaluation

of quality is subjective, and is

therefore a possible source of

disagreement,

particularly between customer and

developer.

A number

of methods for establishing

software quality metrics are

currently being

developed,

though no generally accepted standard

has yet emerged. For

example,

an

initial draft of IEEE

Std-1061 (1990) includes a

detailed discussion of

software

quality

metrics in general, including a

suggested methodology for

applying

metrics,

and many examples and guidelines.

Quality metrics, once defined,

do

indeed

increase objectivity, but

the definition itself is not

necessarily objective

and

greatly depends upon the

needs of the organization

that produces the

definition.

The

basic approach for applying

software quality metrics

requires:

�

The

identification of all required

software quality attributes.

This is usually

derived

from the software

requirements specification.

�

Determinations

of measurable values to be associated

with each quality

attribute.

A description of the method by

which each measurable value will

be

measured.

�

A

procedure for documenting

the results of measuring the

quality of the

software

product.

A set of

many values can be used to

determine the overall

quality of a software

product.

However, a single measure can be

created to represent the overall

quality

of the

software product. This

requires:

�

A

weighted method for

combining the measured

quality attributes into

a

single

measure of quality for the

product.

Some

examples of software metrics

are:

Reliability:

The

percentage of time that the

system is successfully

operational

(e.g. 23

out of 24 hours produces: 100 x

(23/24) percent)

Recoverability:

The

amount of time it takes for

the system to recover after

failure

(e.g.

1hour to reload from backups and 30

minutes to reinitialize the

system)

367

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

User-friendliness:

The

amount of training time

needed for a new user

The

measurement of software quality should

not be performed only at the

end of a

project.

The degree of quality should

be measured at regular intervals

during

development.

Thus, any major reduction in

the overall measure of

quality should

act as a

warning for the project

manager that collective action is

required. High

quality

at the end of the project is

achieved by assuring high

quality throughout

the

development of the

project.

10.9

Some

general guidelines

The

basic software quality

assurance activities cover

the review and approval

of

the

development methodology, the

software and documentation, and

the

supervision

and approval of testing. Other

SQA activities, such as the

supervision

of

reviews, the selection and

approval of development tools, or

the administration

of

configuration control, depend on

the way SQA is adapted to a

specific project.

The size

of the project is usually

the determining factor. The

following guidelines

discuss

some of the parameters to be considered

for different types of

project

when

planning SQA.

�

In small

projects, many SQA

activities can be performed by the

project

manager.

This includes the

organization and supervision of reviews

and

audits,

the evaluation and selection of

development tools, and the

selection

and

application of standards.

�

Test

procedures and testing are always

best when conducted by a

separate

independent

team (discussed later). The

decision on whether supervision

of

testing

activities can be assigned to SQA

depends on many factors,

including

the

independence of the SQA team,

the size of the project and

the 'complexity

of the

project.

�

When

testing is performed by an independent

test team, SQAS involvement

will be

minimal. In most other cases

it will be the responsibility of the

SQA

team to

plan and supervise the

testing of the

system.

�

As a

general guideline, it is usually

undesirable for SQA to be

performed by a

member of

the development team. However,

small projects often

cannot

justify

the cost of a dedicated SQA

engineer. This problem can be

solved by

having a

single SQA engineer

responsible for two or three

small projects (with

each

project funding its share of

the SQA services).

One

additional guideline is based on

the conclusions of Wesselius and

Ververs

(1990)

for the application of effective

quality

control:

368

Software

Project Management

(CS615)

�

The

ability to control software

quality is directly linked to

the quality of the

software

requirements specification. Quality

control requires the

unambiguous

specification

of as many of the required

characteristics of the software

product

as

possible.

369

Table of Contents:

- Introduction & Fundamentals

- Goals of Project management

- Project Dimensions, Software Development Lifecycle

- Cost Management, Project vs. Program Management, Project Success

- Project Management’s nine Knowledge Areas

- Team leader, Project Organization, Organizational structure

- Project Execution Fundamentals Tracking

- Organizational Issues and Project Management

- Managing Processes: Project Plan, Managing Quality, Project Execution, Project Initiation

- Project Execution: Product Implementation, Project Closedown

- Problems in Software Projects, Process- related Problems

- Product-related Problems, Technology-related problems

- Requirements Management, Requirements analysis

- Requirements Elicitation for Software

- The Software Requirements Specification

- Attributes of Software Design, Key Features of Design

- Software Configuration Management Vs Software Maintenance

- Quality Assurance Management, Quality Factors

- Software Quality Assurance Activities

- Software Process, PM Process Groups, Links, PM Phase interactions

- Initiating Process: Inputs, Outputs, Tools and Techniques

- Planning Process Tasks, Executing Process Tasks, Controlling Process Tasks

- Project Planning Objectives, Primary Planning Steps

- Tools and Techniques for SDP, Outputs from SDP, SDP Execution

- PLANNING: Elements of SDP

- Life cycle Models: Spiral Model, Statement of Requirement, Data Item Descriptions

- Organizational Systems

- ORGANIZATIONAL PLANNING, Organizational Management Tools

- Estimation - Concepts

- Decomposition Techniques, Estimation – Tools

- Estimation – Tools

- Work Breakdown Structure

- WBS- A Mandatory Management Tool

- Characteristics of a High-Quality WBS

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- WBS- Major Steps, WBS Implementation, high level WBS tasks

- Schedule: Scheduling Fundamentals

- Scheduling Tools: GANTT CHARTS, PERT, CPM

- Risk and Change Management: Risk Management Concepts

- Risk & Change Management Concepts

- Risk Management Process

- Quality Concept, Producing quality software, Quality Control

- Managing Tasks in Microsoft Project 2000

- Commissioning & Migration