|

THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN |

| << A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES |

| HOW TO DRESS YOUR TYPE >> |

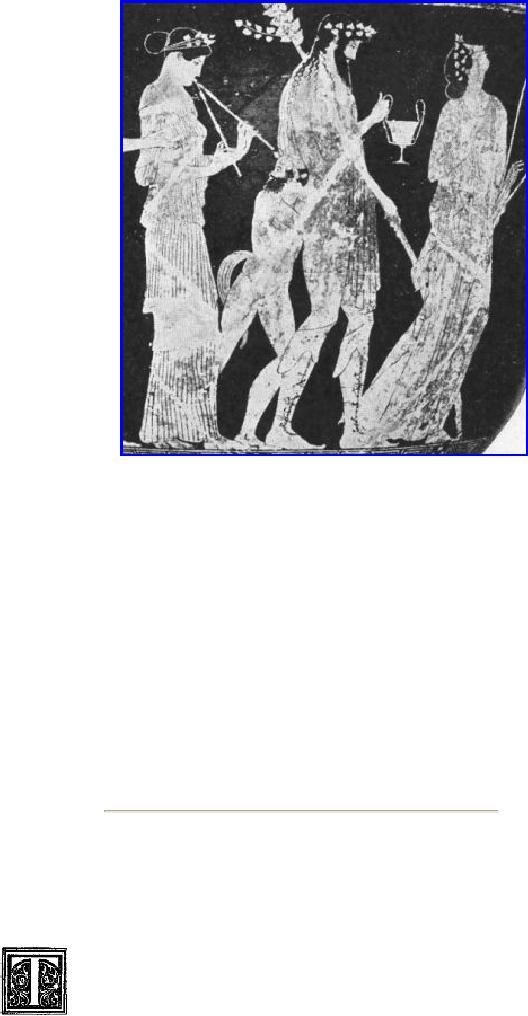

Metropolitan

Museum of Art Woman on Greek

Vase

The

only satisfactory copy of a

Fortuny tea gown we have

ever seen

accomplished

away

from the supervision of

Fortuny himself, was the

exquisite hand-work of a

young

American woman who lives in

New York, and makes

her own gowns and

hats,

because her interest and

talent happen to be in that direction.

She told a group

of

friends the other day, to

whom she was showing a

dainty chiffon gown, posed

on

a

form, that to her, the

planning and making of a lovely

costume had the same

thrilling

excitement that the painting

of a picture had for the

artist in the field

of

paint

and canvas. This same young

woman has worked constantly

since the

European

war began, both in London

and New York, on the

shapeless surgical

shirts

used by the wounded

soldiers. In this, does she

outrank her less

accomplished

sisters?

Yes, for the technique

she has achieved by making

her own costumes

makes

her swift and economical,

both in the cutting of her

material and in the

actual

sewing and she is invaluable as a

buyer of materials.

CHAPTER

II

THE

LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN

HAT

every

costume is either right or

wrong is not a matter of

general

knowledge.

"It will do," or "It is near enough" are

verdicts responsible

for

beauty hidden and interest

destroyed. Who has not

witnessed the mad

mental

confusion of women and men

put to it to decide upon costumes

for some

fancy-dress

ball, and the appalling

ignorance displayed when, at

the costumer's,

they

vaguely grope among battered-looking

garments, accepting those

proffered,

not

really knowing how the

costume they ask for

should look?

Absurd

mistakes in period costumes are to be

taken more or less

seriously

according

to temperament. But where is

the fair woman who will

say that a failure

to

emerge from a dressmaker's hands in a

successful costume is not a

tragedy? Yet

we

know that the average

woman, more often than

not, stands stupefied before

the

infinite

variety of materials and colours of

our twentieth century, and

unless guided

by

an expert, rarely presents

the figure, chez-elle,

or when on view in public

places,

which

she would or could, if in

possession of the few rules

underlying all

successful

dressing, whatever the century or

circumstances.

Six

salient points are to be

borne in mind when planning

a costume, whether for

a

fancy-dress

ball or to be worn as one goes

about one's daily

life:

First,

appropriateness to occasion, station and

age;

Second,

character of background you

are to appear against (your

setting);

Third,

what outline you wish to

present to observers (the period of

costume);

Fourth,

what materials of those in use

during period selected you

will choose;

Fifth,

what colours of those characteristic of

period you will use;

Sixth,

the distinction between those

details which are obvious

contributions to the

costume,

and those which are superfluous,

because meaningless or

line-destroying.

Let

us remind our reader that

the woman who dresses in

perfect taste often

spends

far

less money than she

who has contracted the

habit of indefiniteness as to

what

she

wants, what she should

want, and how to wear what

she gets.

Where

one woman has used her

mind and learned beyond all

wavering what she

can

and what she cannot wear,

thousands fill the streets by

day and places of

amusement

by night, who blithely carry

upon their persons costumes

which hide

their

good points and accentuate their bad

ones.

The

rara avis

among

women is she who always

presents a fashionable outline,

but

so

subtly adapted to her own

type that the impression

made is one of distinct

individuality.

One

knows very well how

little the average costume

counts in a theatre,

opera

house

or ball-room. It is a question of

background again. Also you will observe

that

the

costume which counts most

individually, is the one in a key

higher or lower

than

the average, as with a voice in a

crowded room.

The

chief contribution of our

day to the art of making

woman decorative is

the

quality

of appropriateness. I refer of course to the

woman who lives her

life in the

meshes

of civilisation. We have defined

the smart woman as she

who wears the

costume

best suited to each occasion

when that occasion presents

itself. Accepting

this

definition, we must all

agree that beyond question

the smartest women, as a

nation,

are English women, who

are so fundamentally convinced as to

the

invincible

law of appropriateness that from

the cradle to the grave,

with them

evening

means an evening gown;

country clothes are suited

to country uses and a

tea-gown

is not a bedroom neglig�e.

Not even in Rome can they be

prevailed upon

"to

do as the Romans do."

Apropos

of this we recall an experience in

Scotland. A house party had gathered

for

the

shooting,--English men and women.

Among the guests were

two Americans;

done

to a turn by Redfern. It really

turned out to be a tragedy, as

they saw it,

for

though

their cloth skirts were

short, they were silk-lined;

outing shirts were of

cr�pe--not

flannel; tan boots, but

thinly soled; hats most

chic, but the sort

that

drooped

in a mist. Well, those two

American girls had to choose

between long days

alone,

while the rest tramped the

moors, or to being togged out in

borrowed tweeds,

flannel

shirts and thick-soled

boots.

PLATE

IV

Greek

Kylix. Signed by Hieron, about

400

B.C.

Athenian. The woman wears

one of the

gowns

Fortuny (Paris) has

reproduced as a

modern

tea gown. It is in two

pieces. The

characteristic

short tunic reaches just

below

waist

line in front and hangs in long,

fine

pleats

(sometimes cascaded folds)

under the

arms,

the ends of which reach

below knees.

The

material is not cut to form

sleeves;

instead

two oblong pieces of

material are held

together

by small fastenings at short

intervals,

showing

upper arm through

intervening

spaces.

The result in appearance is

similar to

a

kimono sleeve. (Metropolitan

Museum.)

Metropolitan

Museum of Art Woman in

Greek

Art

about 400 B.C.

That

was some years back. We are a

match for England to-day, in

the open, but

have

a long way to go before we

wear with equal conviction,

and therefore easy

grace,

tea-gown and evening dress.

Both how

and

when

still

annoy us as a nation.

On

the street we are supreme when

tailleur.

In carriage attire the French

woman is

supreme,

by reason of that innate

Latin coquetry which makes

her feel

line

and its

significance.

The ideal pose for

any hat is a French

secret.

The

average woman is partially aware

that if she would be a

decorative being, she

must

grasp conclusively two

points: first, the

limitations of her natural

outline;

secondly,

a knowledge of how nearly

she can approach the outline

demanded by

fashion

without appearing a caricature, which is

another way of saying that

each

woman

should learn to recognise her

own type. The discussion of

silhouette has

become

a popular theme. In fact it

would be difficult to find a

maker of women's

costumes

so remote and unread as not to

have seized and imbedded deep in

her

vocabulary

that mystic word.

To

make our points clear,

constant reference to the stage is

necessary; for from

stage

effects we are one and all

free to enjoy and learn.

Nowhere else can the

woman

see so clearly presented the

value of having what she

wears harmonise with

the

room she wears it in, and

the occasion for which it is

worn.

Not

all plays depicting

contemporary life are plays

of social life, staged

and

costumed

in a chic manner. What is

taught by the modern stage,

as shown by Bakst,

Reinhardt,

Barker, Urban, Jones, the

Portmanteau Theatre and Washington

Square

Players,

is values,

as the artist uses the

term--not fashions; the

relative importance

Table of Contents:

- A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES

- THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN

- HOW TO DRESS YOUR TYPE

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CLOTHES

- ESTABLISH HABITS OF CARRIAGE WHICH CREATE GOOD LINE

- COLOUR IN WOMAN'S COSTUME

- FOOTWEAR

- JEWELRY AS DECORATION

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER BOUDOIR

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER SUN-ROOM

- I. WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER GARDEN:WOMAN DECORATIVE ON THE LAWN

- WOMAN AS DECORATION WHEN SKATING

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER MOTOR CAR

- HOW TO GO ABOUT PLANNING A PERIOD COSTUME

- I. THE STORY OF PERIOD COSTUMES:II. EGYPT AND ASSYRIA

- DEVELOPMENT OF GOTHIC COSTUME

- THE RENAISSANCE

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- WOMAN IN THE VICTORIAN PERIOD

- SEX IN COSTUMING

- LINE AND COLOUR OF COSTUMES IN HUNGARY

- STUDYING LINE AND COLOUR IN RUSSIA

- MARK TWAIN'S LOVE OF COLOUR IN ALL COSTUMING

- THE ARTIST AND HIS COSTUME

- IDIOSYNCRASIES IN COSTUME

- NATIONALITY IN COSTUME

- MODELS

- WOMAN COSTUMED FOR HER WAR JOB

- IN CONCLUSION