|

A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES |

| << CONTENTS:ILLUSTRATIONS |

| THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN >> |

"When

was that 'simple time of

our fathers' when people

were

too

sensible to care for fashions? It

certainly was before

the

Pharaohs, and

perhaps before the Glacial

Epoch."

W. G.

SUMNER,

in Folkways.

CHAPTER

I

A

FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER

COSTUMES

HERE

are a

few rules with regard to the

costuming of woman which if

understood

put one a long way on the

road toward that desirable

goal--

decorativeness,

and have economic value as

well. They are simple

rules

deduced

by those who have made a

study of woman's lines

and

colouring,

and how to emphasise or modify

them by dress.

Temperaments

are seriously considered by experts in

this art, for the carriage

of a

woman

and her manner of wearing

her clothes depends in part

upon her

temperament.

Some women instinctively

feel line

and are graceful in consequence,

as

we have said, but where one is

not born with this

instinct, it is possible to

become

so thoroughly schooled in the

technique of controlling the

physique--poise

of

the body, carriage of the head,

movement of the limbs, use

of feet and hands,

that

a sense of line is acquired.

Study portraits by great masters, the

movements of

those

on the stage, the carriage and

positions natural to graceful

women. A graceful

woman

is invariably a woman highly sensitised,

but remember that "alive to

the

finger

tips"--or toe tips, may be

true of the woman with

few gestures, a quiet

voice

and

measured words, as well as

the intensely active

type.

The

highly sensitised woman is

the one who will wear her

clothes with

individuality,

whether she be rounded or

slender. To dress well is an

art, and

requires

concentration as any other

art does. You know the

old story of the

boy,

who

when asked why his necktie

was always more neatly tied

than those of his

companions,

answered: "I put my whole

mind on it." There you

have it! The

woman

who puts her whole

mind on the costuming of

herself is naturally going

to

look

better than the woman

who does not, and having

carefully studied her

type,

she

will know her strong points

and her weak ones, and by accentuating

the former,

draw

attention from the latter.

There is a great difference, however,

between

concentrating

on dress until an effect is

achieved, and then turning

the mind to

other

subjects, and that tiresome

dawdling, indefinite, fruitless

way, to arrive at no

convictions.

This variety of woman never

gets dress off her

chest.

The

catechism of good dressing might be given

in some such form as this:

Are you

fat?

If so, never try to look

thin by compressing your

figure or confining

your

clothes

in such a way as to clearly

outline the figure. Take a

chance from your

size.

Aim

at long lines, and what

dressmakers call an "easy

fit," and the use of

solid

colours.

Stripes, checks, plaids, spots and

figures of any kind draw

attention to

dimensions;

a very fat woman looks

larger if her surface is

marked off into

many

spaces.

Likewise a very thin woman

looks thinner if her body on

the imagination of

the

public subtracting

is

marked off into spaces

absurdly few in number.

A

beautifully

proportioned and rounded figure is

the one to indulge in

striped,

checked,

spotted or flowered materials or any

parti-coloured costumes.

Never

try to make a thin woman

look anything but thin.

Often by accentuating

her

thinness,

a woman can make an effect as

type,

which gives her distinction.

If she

were

foolish enough to try to

look fatter, her lines

would be lost without

attaining

the

contour of the rounded type.

There are of course fashions in

types; pale ash

blonds,

red-haired types (auburn or

golden red with shell pink

complexions), dark

haired

types with pale white skin,

etc., and fashions in figures

are as many and as

fleeting.

Artists

are sometimes responsible for

these vogues. One hears of

the Rubens type,

or

the Sir Joshua Reynolds,

Hauptner, Burne-Jones, Greuse,

Henner, Zuloaga, and

others.

The artist selects the

type and paints it,

the attention of the public

is

attracted

to it and thereafter singles it out. We

may prefer soft, round

blonds with

dimpled

smiles, but that does

not mean that such

indisputable loveliness can

challenge

the attractions of a slender

serpentine tragedy-queen, if the

latter has

established

the vogue of her type

through the medium of the

stage or painter's

brush.

A

woman well known in the

world of fashion both sides

of the Atlantic, slender

and

very

tall, has at times

deliberately increased that

height with a small

high-crowned

hat,

surmounted by a still higher

feather. She attained

distinction without

becoming

a

caricature, by reason of her

obvious breeding and reserve.

Here is an important

point.

A woman of quiet and what we

call conservative type, can

afford to wear

conspicuous

clothes if she wishes, whereas a

conspicuous type must

be

reserved in

her

dress. By following this

rule the overblown rose

often makes herself

beautiful.

Study

all types of woman. Beauty

is a wonderful and precious thing, and

not so

fleeting

either as one is told. The

point is, to take note, not

of beauty's departure,

but

its gradually changing

aspect, and adapt costume,

line and colour, to

the

demands

of each year's alterations in the

individual. Make the most of

grey hair; as

you

lose your colour, soften

your tones.

Always

star your points. If you happen to

have an unusual amount of

hair, make it

count,

even though the fashion be

to wear but little. We

recall the beautiful

and

unique

Madame X. of Paris, blessed by the

gods with hair like

bronze, heavy, long,

silken

and straight. She wore it

wrapped about her head and

finally coiled into a

French

twist on the top, the

effect closely resembling an

old Roman helmet.

This

was

design, not chance, and her well-modeled

features were the sort to

stand the

severe

coiffure, Madame's husband, always at

her side that season on

Lake

Lucerne,

was curator of the Louvre. We

often wondered whether the

idea was his

or

hers. She invariably wore

white, not a note of colour,

save her hair; even

her

well-bred

fox terrier was snowy

white.

Worth

has given distinction to

more than one woman by

recognising her

possibilities,

if kept to white, black,

greys and mauves. A

beautiful Englishwoman

dressed

by this establishment, always a

marked figure at whatever

embassy her

husband

happens to be posted, has never

been seen wearing anything

in the evening

but

black, or white, with very

simple lines, cut low and

having a narrow

train.

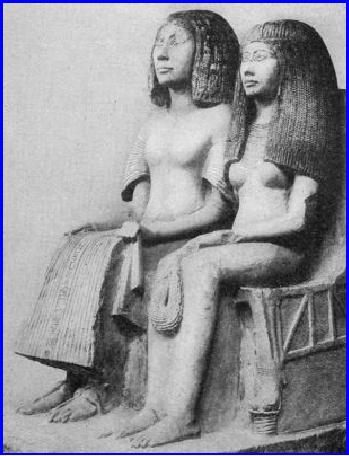

PLATE

II

Woman

in ancient Egyptian

sculpture-relief

about

1000 B.C.

We

have here a

husband

and

wife.

(Metropolitan

Museum.)

Metropolitan

Museum of Art

Woman

in Ancient Egyptian

Sculpture-Relief

It

may take courage on the part of

dressmaker, as well as the woman in

question,

but

granted you have a distinct

style of your own, and

understand it, it is the

part of

wisdom

to establish the habit of those

lines and colours which are

yours, and then

to

avoid experiments with

outr�

lines

and shades. They are almost

sure to prove

failures.

Taking on a colour and its

variants is an economic, as well as an

artistic

measure.

Some women have so systematised

their costuming in order to

be

decorative,

at the least possible expenditure of

vitality and time (these are

the

women

who dress to live, not

live to dress), that they

know at a glance, if

dress

materials,

hats, gloves, jewels, colour

of stones and style of setting,

are for them. It

is

really a joy to shop with

this kind of woman. She

has definitely fixed in her

mind

the

colours and lines of her

rooms, all her habitual

settings, and the clothes

and

accessories

best for

her. And

with the eye of an artist,

she passes swiftly by

the

most

alluring bargains, calculated to

undermine firm resolution. In

fact one should

not

say that this woman shops;

she buys. What is more,

she never wastes

money,

though

she may spend it

lavishly.

Some

of the best dressed women

(by which we always mean

women dressed

fittingly

for the occasion, and with reference to

their own particular types)

are those

with

decidedly limited

incomes.

There

are women who suggest

chiffon and others brocade; women

who call for

satin,

and others for silk; women

for sheer muslins, and

others for heavy

linen

weaves;

women for straight brims,

and others for those that

droop; women for

leghorns,

and those they do not suit;

women for white furs, and

others for tawny

shades.

A woman with red in her hair

is the one to wear red

fox.

If

you cannot see for

yourself what line and

colour do to you, surely you

have some

friend

who can tell you. In

any case, there is always

the possibility of paying

an

expert

for advice. Allow yourself

to be guided in the reaching of

some decision

about

yourself and your limitations, as

well as possibilities. You will by this

means

increase

your decorativeness, and what is of more

serious importance, your

economic

value.

A

marked example of woman

decorative was seen on the

recent occasion when

Miss

Isadora Duncan danced at the

Metropolitan Opera House, for

the benefit of

French

artists and their families,

victims of the present war.

Miss Duncan was

herself

so marvelous that afternoon, as

she poured her art,

aglow and vibrant

with

genius,

into the mould of one classic

pose after another, that

most of her audience

had

little interest in any other

personality, or effect. Some of

us, however, when

scanning

the house between the acts,

had our attention caught and

held by a

charmingly

decorative woman occupying one of

the boxes, a quaint outline

in

silver-grey

taffeta, exactly matching

the shade of the woman's

hair, which was cut

in

Florentine fashion forming an

aureole about her small

head,--a becoming

frame

for

her fine, highly sensitive

face. The deep red curtains and

upholstery in the box

threw

her into relief, a lovely

miniature, as seen from a distance.

There were no

doubt

other charming costumes in the boxes

and stalls that afternoon,

but none so

successful

in registering a distinct decorative

effect. The one we refer to

was

suitable,

becoming, individual, and

reflected personality in a way to

indicate an

extraordinary

sensitiveness to values, that subtle

instinct which makes the

artist.

With

very young women it is easy

to be decorative under most

conditions. Almost

all

of them are decorative, as

seen in our present fashions,

but to produce an

effect

in

an opera box is to understand

the carrying

power of colour

and line. The woman

in

the opera box has

the same problem to solve as

the woman on the stage:

her

costume

must be effective at a distance. Such a

costume may be white, black

and

any

colour; gold, silver, steel or

jet; lace, chiffon--what you

will--provided the

fact

be kept in mind that your

outline be striking and the

colour an agreeable

contrast

against the lining of the

box. Here, outline is of

chief importance, the

silhouette

must be definite; hair,

ornaments, fan, cut of gown,

calculated to register

against

the background. In the

stalls, colour and outline of

any single costume

become

a part of the mass of colour

and black and white of the audience. It

is

difficult

to be a decorative factor under

these conditions, yet we can

all recall

women

of every age, who so costume

themselves as to make an artistic,

memorable

impression,

not only when entering

opera, theatre or concert

hall, but when

seated.

These

are the women who

understand the value of

elimination, restraint,

colour

harmony

and that chic which results

in part from faultless

grooming. To-day it is

not

enough to possess hair which

curls ideally: it must, willy

nilly, curl

conventionally!

If

it is necessary, prudent or wise that

your purchases for each

season include not

more

than six new gowns,

take the advice of an

actress of international

reputation,

who

is famous for her good dressing in

private life, and make a point of

adding one

new

gown to each of the six

departments of your wardrobe.

Then have the

cleverness

to appear in these costumes whenever on

view, making what you

have

fill

in between times.

To

be clear, we would say, try

always to begin a season

with one distinguished

evening

gown, one smart tailor suit,

one charming house gown, one tea

gown, one

neglig�e

and one sport suit. If you

are needing many dancing

frocks, which have

hard

wear, get a simple, becoming

model, which your little

dressmaker, seamstress

or

maid can copy in inexpensive

but becoming colours. You can do

this in Summer

and

Winter alike, and with

dancing frocks, tea gowns,

neglig�es and even sport

suits.

That is, if you have

smart, up-to-date models to

copy.

One

woman we know bought the

finest quality jersey cloth

by the yard, and had a

little

dressmaker copy exactly a

very expensive skirt and

sweater. It seems

incredible,

but she saved on a ready

made suit exactly like it

forty dollars, and on

one

made to measure by an exclusive

house, one hundred dollars!

Remember,

however,

that there was an artist back of it

all and someone had to pay

for that

perfect

model, to start with. In the

case we cite, the woman had

herself bought the

original

sport suit from an importer

who is always in advance with

Paris models.

If

you cannot buy the

designs and workmanship of artists, take

advantage of all

opportunities

to see them; hats and gowns

shown at openings, or when

your richer

friends

are ordering. In this way

you will get ideas to make

use of and you will

avoid

looking home-made, than

which, no more damning

phrase can be applied to

any

costume. As a matter of fact it

implies a hat or gown

lacking an artist's

touch

and

describes many a one turned

out by long-established and

largely patronised

firms.

PLATE

III

A

Greek vase. Dionysiac scenes

about 460

B.C.

Interesting costumes.

(Metropolitan

Museum.)

Table of Contents:

- A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES

- THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN

- HOW TO DRESS YOUR TYPE

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CLOTHES

- ESTABLISH HABITS OF CARRIAGE WHICH CREATE GOOD LINE

- COLOUR IN WOMAN'S COSTUME

- FOOTWEAR

- JEWELRY AS DECORATION

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER BOUDOIR

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER SUN-ROOM

- I. WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER GARDEN:WOMAN DECORATIVE ON THE LAWN

- WOMAN AS DECORATION WHEN SKATING

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER MOTOR CAR

- HOW TO GO ABOUT PLANNING A PERIOD COSTUME

- I. THE STORY OF PERIOD COSTUMES:II. EGYPT AND ASSYRIA

- DEVELOPMENT OF GOTHIC COSTUME

- THE RENAISSANCE

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- WOMAN IN THE VICTORIAN PERIOD

- SEX IN COSTUMING

- LINE AND COLOUR OF COSTUMES IN HUNGARY

- STUDYING LINE AND COLOUR IN RUSSIA

- MARK TWAIN'S LOVE OF COLOUR IN ALL COSTUMING

- THE ARTIST AND HIS COSTUME

- IDIOSYNCRASIES IN COSTUME

- NATIONALITY IN COSTUME

- MODELS

- WOMAN COSTUMED FOR HER WAR JOB

- IN CONCLUSION