|

ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING |

| << PRACTICAL PROBLEMS |

| DECORATIVE DRAWING >> |

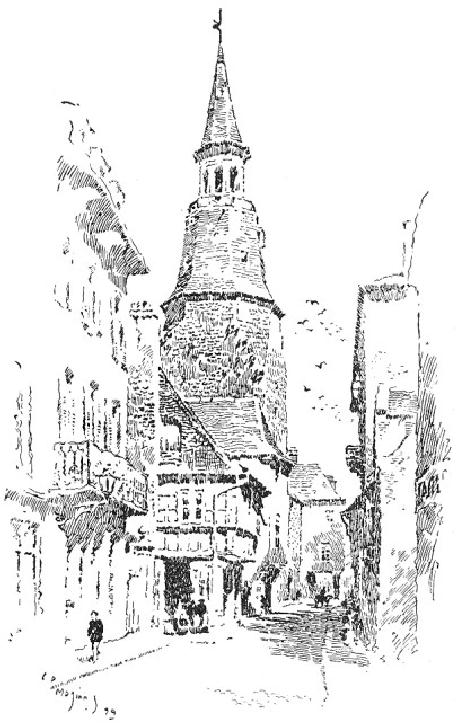

FIG.

40

C.

D. M.

To

add interest to the picture,

and more especially to give

life to the

shadows,

several figures are

introduced. It will be noticed that

the cart is

inserted

at the focal point of the

drawing to better assist the

perspective.

CHAPTER

VI

ARCHITECTURAL

DRAWING

It

is but a few years since architects'

perspectives were "built up"

(it

would

be a mistake to say "drawn") by means of

a T-square and the

ruling

pen; and if architectural drawing

has not quite kept

pace with that

for

general illustration since, a

backward glance over the

professional

magazines

encourages a feeling of comparative

complacency. That so

high

a standard or so artistic a character is

not observable in

architectural

as

in general illustration is, I

think, not difficult to

explain. Very few of

the

clever architectural draughtsmen

are illustrators by profession.

Few,

even

of those who are generally

known as illustrators, are

anything

more--I

should perhaps say anything

less--than

versatile architects; and

yet

Mr. Pennell, who would

appear to assume, in his

book on drawing,

that

the point of view of the

architect is normally pictorial,

seems at a

loss

to explain why Mr. Robert Blum,

for instance, can illustrate

an

architectural

subject more artistically

than any of the draughtsmen

in the

profession.

Without accepting his premises, it is

remarkably creditable to

architecture

that it counts among its

members in this country such

men as

Mr.

B. G. Goodhue and Mr. Wilson Eyre,

Jr., and in England

such

thorough

artists as Mr. Prentice and Mr.

Ernest George--men

known

even

to distinction for their

skill along lines of purely

architectural

practice,

yet any one of whom would, I

venture to say, cause

considerable

displacement did he invade

the ranks of magazine

illustrators.

Moreover (and the suggestion is

not unkindly offered),

were

the

architects and the illustrators to change

places architecture

would

suffer

most by the process.

That

the average architect should

be incapable of artistically illustrating

The

his

own design, ought, I think,

to be less an occasion for surprise

than Architects'

that

few painters, whose point of

view is essentially pictorial, can make

Case

even

a tolerable interpretation in line of

their own paintings. Be

it

remembered

that the pictures made by

the architect are seldom

the

records

of actualities. The

buildings themselves

are merely

contemplated,

and the illustrations are

worked up from

geometrical

elevations

in the office, very, very

far from Nature. Moreover,

the

subjects

are not infrequently such as

lend themselves with an ill

grace to

picturesque

illustration. The structure to be

depicted may, for

instance,

be

a heavy cubical mass with a

bald uninteresting sky-line; or it

may be a

tall

office building, impossible to

reconcile with natural

accessories

either

in pictorial scale or in composition.

These natural accessories,

too,

the

draughtsman must, with an

occasional recourse to his

photograph

album,

evolve out of his inner

consciousness. When it is further

considered

that such structures,

even when actualities,

are

uncompromisingly

stiff and immaculate in their

newness, presenting

absolutely

none of those interesting accidents so

dear to the artist,

and

perhaps

with nothing whatever about

them of picturesque suggestion,

we

have

a problem presented which is

somewhat analogous to that

presented

by

the sculpturesque possibilities of

"fashionable trousering." That,

with

such

uninspiring conditions, architectural

illustration does not

develop so

interesting

a character nor attain to so

high a standard as distinguishes

general

illustration is not to be wondered

at. It is rather an occasion

for

surprise

that it exhibits so little of

the artificiality of the

fashion-plate

after

all, and that the better

part of it, at least, is not

more unworthy than

figure

illustration would be were it denied

the invaluable aid of the

living

model.

So much by way of

apology.

The

architectural perspective, however, is

not to be regarded purely

The

from

the pictorial point of view.

It is an illustration first, a picture

Architects'

afterwards,

and almost invariably deals

with an individual building,

Point of

View

which

is the essential subject. This

building cannot, therefore, be

made a

mere

foil for interesting

"picturesqueries," nor subordinated to

any scenic

effect

of landscape or chiaroscuro. Natural

accessories or interesting

bits

of

street life may be added to

give it an appropriate setting; but

the result

must

clearly read "Building, with

landscape," not "Landscape,

with

building."

Much

suggestion for the

sympathetic handling of particular

subjects

may

be found in the character of

the architecture itself. The

illustrator

ought

to enter into the spirit of

the designer, ought to feel

just what

natural

accessories lend themselves

most harmoniously to this or

that

particular

type. If the architecture be

quaint and picturesque it must

not

have

prosaic surroundings. If, on the other

hand, it be formal or

monumental,

the character and scale of

the accessories should

be

accordingly

serious and dignified. The rendering

ought also to vary

with

the

subject,--a free picturesque

manner for the one, a

more studied and

responsible

handling for the other.

Technique is the language of

art, and

a

stiff pompous phraseology will accord ill

with a story of quaint

humor

or

pathos, while the homely

diction that might answer

very well would

be

sure to struggle at a disadvantage with

the stately meanings

and

diplomatic

subtleties of a state

document.

It

would be well for the

student, before venturing

upon whole subjects,

Rendering

of

to

learn to render details,

such as windows, cornices,

etc. Windows are a Detail

most

important feature of the

architectural drawing, and the

beginner

must

study them carefully,

experimenting for the method

which will best

represent

their glassy surfaces. No material

gives such play of light

and

shade

as glass does. One window is

never absolutely like

another; so that

while

a certain uniformity in their

value may be required for

breadth of

effect

in the drawing of a building,

there is plenty of opportunity

for

incidental

variety in their

treatment.

A

few practical hints on the

rendering of windows may

prove

serviceable.

Always emphasize the sash.

Where there is no recess, as

in

wooden

buildings, strengthen the

inner line of sash, as in

Fig. 41. In

masonry

buildings the frame and

sash can be given their

proper values,

the

area of wood being treated

broadly, without regard to the

individual

members.

The wood may, however, be

left white if required, as

would be

the

case in Colonial designs. In either

case the dark shadow

which the

sash

casts on the glass should be

suggested, if the scale of

the drawing be

such

as to permit of it. Do not

try to show too much.

One is apt to make a

fussy

effect, if, for instance,

one insists on always shading

the soffit of

the

masonry opening, especially if

the scale of the drawing be

small.

Besides,

a white soffit is not a

false but merely a forced

value, as in

strong

sunlight the reflected light

is considerable. If the frame be

left

white,

however, the soffit ought to

be shaded, otherwise it will be

difficult

to keep the values distinct.

In respect of wooden buildings

there

is

no need to always complete

the mouldings of the

architrave. Notice in

Fig.

41 that, in the window

without the muntins, the

mouldings have

been

carried round the top to

give color, but that in

the other they

are

merely

suggested at the corners so as to

avoid confusion. Care should

be

taken

to avoid mechanical rendering of

the muntins. For the

glass itself, a

uniformly

flat tone is to be avoided.

The tones should soften

vaguely. It

will

be found, too, that it is

not advisable to have a

strong dark effect at

the

top of the window and

another at the bottom; one

should

predominate.

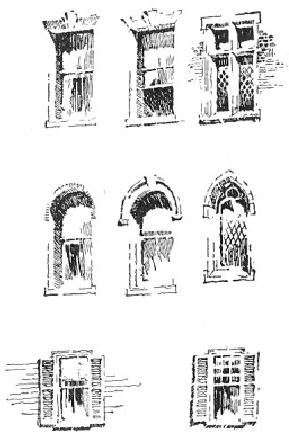

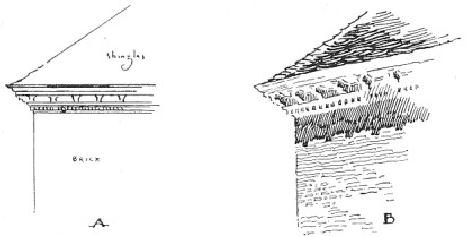

FIG.

41

C.

D. M.

The

student after careful study

of Fig. 41 should make from it

enlarged

drawings,

and afterwards, laying the

book aside, proceed to

render them

in

his own way. When he

has done so, let him compare

his work with

the

originals.

This process ought to be

repeated several times, the

aim being

always

for similarity,

not for literalness

of

effect. If he can get

equally

good

results with another method

he need not be disconcerted at the

lack

of

any further resemblance.

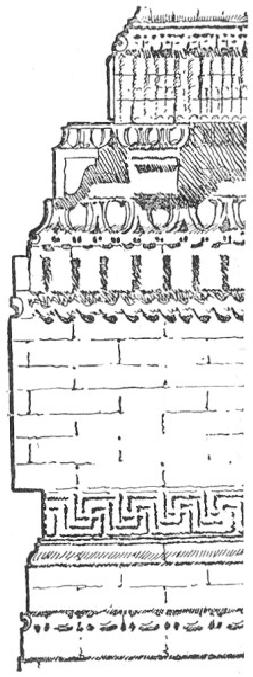

The

cornice with its shadow is

another salient feature. In

short

shadows,

such as those cast by cornices, it is

well, if a sunny effect

be

desired,

to accent the bottom edge of

the shadow. The shadow

lines

ought

to be generally parallel, but

with enough variation to

obviate a

mechanical

effect. They need not be

vertical lines,--in fact it is

better

that

they should take the same

slant as the light. If they

are not absolutely

perpendicular,

however, it is well to make them

distinctly oblique,

otherwise

the effect will be unpleasant. A

clever sketch of a cornice

by

Mr.

George F. Newton is shown in Fig.

42. Notice how well

the texture

of

the brick is expressed by

the looseness of the pen

work. Some of the

detail,

too, is dexterously handled,

notably the bead and

button

moulding.

The

strength of the cornice

shadow should be determined by

the tone

of

the roof above it. To obtain

for this shadow the

very distinct value

which

it ought to have, however,

does not require that

the roof be kept

always

much lighter than it. In

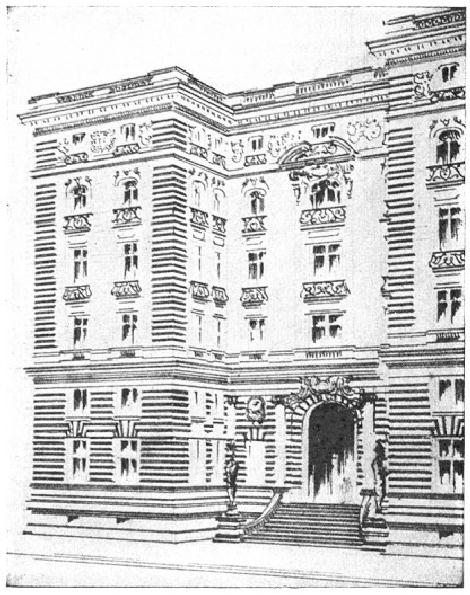

the gable roof in Fig. 57,

the tone of the

roof

is shaded lighter as it approaches

the eaves, so that the

shadow may

count

more emphatically. This

order may be reversed, as in the

case of a

building

with dark roof and light

walls, in which case the

shadow may be

grayer

than the lower portion of

the roof, as in "B" in Fig.

44.

FIG.

42

GEORGE

F. NEWTON

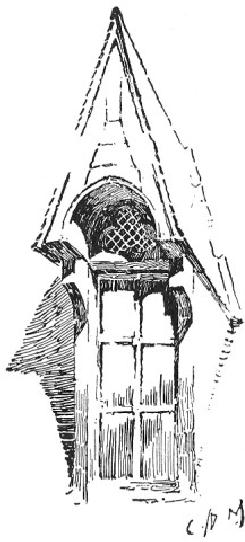

But

the beginner should not

yet hurry on to whole

subjects. A church

porch,

as in Fig. 35, or a dormer

with its shadow cast on a

roof, as in Fig.

43,

will be just as beneficial a study

for him as an entire

building, and

will

afford quite as good an opportunity

for testing his knowledge of

the

principles

of pen drawing, with the

added advantage that either of

the

subjects

mentioned can be mapped out

in a few minutes, and that

a

failure

or two, therefore, will not

prove so discouraging as if a

more

intricate

subject had to be re-drawn. I have

known promising

beginners

to

give up pen and ink drawing

in despair because they

found themselves

unequal

to subjects which would have

presented not a few

difficulties to

the

experienced illustrator. When the

beginner grows faint-hearted,

let

him

seek consolation and encouragement in

the thought that were

pen

drawing

something to be mastered in a week or a

month there would be

small

merit in the

accomplishment.

FIG.

43

C.

D. M.

It

is a common fault of students to

dive into the picture

unthinkingly, A

General

beginning

anywhere, without the

vaguest plan of a general

effect, System

whereas

it is of the utmost importance

that every stroke of the pen

be

made

with intelligent regard to the

ultimate result. The

following general

method

will be found valuable.

Pencil

the outline of the entire

subject before beginning the

pen work.

It

will not do to start on the

rendering as soon as the building

alone is

pencilled

out, leaving the accessories

to be put in as one goes along.

The

adjacent

buildings, the foliage, and

even the figures must be

drawn--

carefully

drawn--before the pen is taken

up. The whole subject

from the

very

beginning should be under

control, and to that end it

becomes

necessary

to have all the elements of

it pre-arranged.

Next

scheme out the values.

This is the time to do the

thinking. Do not Arrangement

start

out rashly as soon as everything is

outlined in pencil, confident in

of the

Values

the

belief that all windows,

for instance, are dark, and

that you may as

well

make them so at once and be done with

them. This will be only

to

court

disaster. Besides, all windows

are not dark; they

may be very light

indeed.

The color value of nothing

is absolute. A shadow may

seem

almost

black till a figure passes

into it, when it may

become quite gray

by

comparison. So a window with

the sun shining full upon

it, or even

one

in shade, on which a reflected

light is cast, may be

brilliantly light

until

the next instant a cloud

shadow is reflected in it,

making it densely

black.

Arrange the values,

therefore, with reference to one

general effect,

deciding

first of all on the

direction of the light.

Should this be such as

to

throw

large areas of shadow, these

masses of gray will be

important

elements

in the color-scheme. An excellent

way to study values is

to

make

a tracing-paper copy of the

line drawing and to experiment on

this

for

the color with charcoal,

making several sketches if necessary.

After

having

determined on a satisfactory scheme, put

fixatif on the rough

sketch

and keep it in sight.

Otherwise, one is liable, especially if

the

subject

is an intricate one, to be led

astray by little opportunities

for

interesting

effects here and there, only to

discover, when too late,

that

these

effects do not hang together

and that the drawing

has lost its

breadth.

The rough sketch is to the

draughts man what manuscript

notes

are

to the lecturer.

Do

not be over-conscious of detail. It is a

common weakness of the

Treatment

of

architectural

draughts man to be too sophisticated in

his pictorial Detail

illustration.

He knows so much about the

building that no matter

how

many

thousand yards away from it

he may stand he will see things

that

would

not reveal themselves to

another with the assistance

of a field-

glass.

He is conscious of the fact

that there are just so

many brick

courses

to the foot, that the

clapboards are laid just so

many inches to the

weather,

that there are just so

many mouldings in the belt

course,--that

everything

in general is very, very

mathematical. This is not

because his

point

of view is too big, but

because it is too small. He

who sees so much

never

by any chance sees the

whole

building. Let

him try to think

broadly

of things. Even should he

succeed in forgetting some of

these

factitious

details, the result will

still be stiff enough, so

hard is it to re-

adjust

one's attitude after

manipulating the T-square. I

strongly

recommend,

as an invaluable aid toward such a

re-adjustment, the

habit

of

sketching from Nature,--from

the figure during the

winter evenings,

and

out of doors in summer.

FIG.

44

C.

D. M.

The

beginner is apt to find his

effects at first rather hard

and

mechanical

at the best, because he has

not yet attained that

freedom of

handling

which ignores unimportant

details, suggests rather

than states,

gives

interesting variations of line

and tone, and differentiates

textures. A

good

part of the unpleasantness of effect will

undoubtedly be found to be

due

to a mistaken regard for accuracy of

statement, individual

mouldings

being

lined in as deliberately as in the

geometrical office drawings,

and

not

an egg nor a dart slighted.

Take, for example, the

case of an old

Colonial

building with its white

cornice, or any building

with white

trimmings.

See the effect of such a one

in an "elevation" where all

the

detail

is drawn, as in "A," Fig. 44.

Observe that the amount of

ink

necessary

to express this detail has

made the cornice darker

than the rest

of

the drawing, and yet

this is quite the reverse of

the value which it

would

have in the actual building,

see "B." To obtain the

true value the

different

mouldings which make up the

cornice should be

merely

suggested.

Where it is not a question of

local color, however, this

matter

of

elimination is largely subject to

the exigencies of reproduction;

the

more

precisely and intimately one attempts to

render detail, the

smaller

the

scale of the technique

requires to be, and the greater

the difficulty.

Consequently,

the more the reduction

which the drawing is likely

to

undergo

in printing, the more one will be

obliged to disregard the

finer

details.

These finer details need

not, however, be absolutely

ignored.

Notice,

for instance, the clever

suggestion of the sculpture in

the

admirable

drawing by Mr. F. E. Wallis, Fig.

45. The conventional

drawing

of the fa�ade, Fig. 46, is a

fine illustration of the

decorative

effect

of color obtainable by emphasizing

the organic lines of the

design.

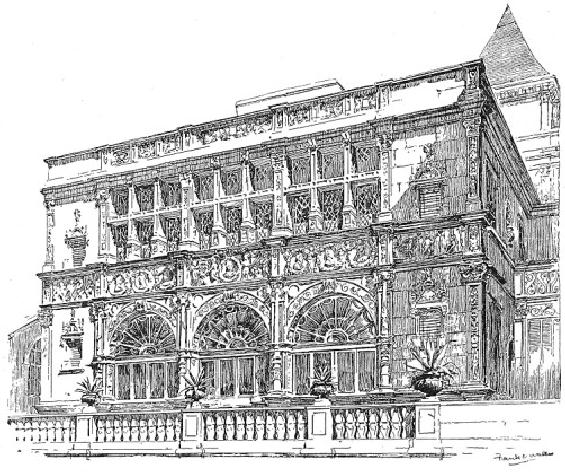

FIG.

45

FRANK

E. WALLIS

The

elements in a perspective drawing which

present most difficulties Foliage

and

to

the architectural draughtsman

are foliage and figures. These are,

Figures

however,

most important accessories, and

must be cleverly handled. It

is

difficult

to say which is the harder to

draw, a tree or a human figure;

and

if

the student has not sketched

much from Nature either will

prove a

stumbling-block.

Presuming, therefore, that he

has already filled a

few

sketch-books,

he had better resort to these, or to his

photograph album,

when

he needs figures for his

perspective. Designing figures and

trees

out

of one's inner consciousness is slow

work and not very

profitable;

and

if the figure draughtsman

may employ models, the

architect may be

permitted

to use photographs.

FIG.

46

HARRY

ALLAN JACOBS

Unhappily

for the beginner, no two

illustrators consent to

render

foliage,

or anything else for that

matter, in quite the same

way, and so I

cannot

present any authoritative formula

for doing so. This

subject has

been

treated, however, in a previous chapter,

and nothing need be

added

here

except to call attention to an

employment of foliage peculiar

to

architectural

drawings. This is the broad

suggestive rendering of

dark

leafage

at the sides of a building, to

give it relief. The example

shown in

Fig.

47 is from one of Mr. Gregg's

drawings.

FIG.

47

D.

A. GREGG

The

rendering of the human

figure need not be dealt

with under this

head,

as figures in an architectural subject

are of necessity

relatively

small,

and therefore have to be rendered very

broadly. Careful drawing

is

none

the less essential, however, if

their presence is to be justified;

and

badly

drawn figures furnish a

tempting target for the

critic of

architectural

pictures. Certainly, it is only

too evident that the

people

usually

seen in such pictures are

utterly incapable of taking

the slightest

interest

whatever in architecture, or in anything

else; and not infrequently

they

seem to be even more

immovable objects than the

buildings

themselves,

so fixed and inflexible are

they. Such figures as these

only

detract

from the interest of the

drawing, instead of adding to it, and

the

draughtsman

who has no special aptitude is

wise in either omitting

them

altogether,

or in using very few, and is

perhaps still wiser if he

entrusts

the

drawing of these to one of his

associates more accomplished in

this

special

direction.

The

first thing to decide in the

matter of figures is their

arrangement

and

grouping, and when this has

been determined they should

be

sketched

in lightly in pencil. In this

connection a few words by

way of

suggestion

may be found useful. Be

careful to avoid anything

like an

equal

spacing of the figures. Group

the people interestingly. I have

seen

as

many as thirty individuals in a

drawing, no two of whom

seemed to be

acquainted,--a

very unhappy condition of

affairs even from a

purely

pictorial

point of view. Do not

over-emphasize the base of a

building by

stringing

all the figures along

the sidewalks. The lines of

the curbs would

thus

confine and frame them in

unpleasantly. Break the

continuity of the

street

lines with figures or

carriages in the roadway, as in

Fig. 55. After

the

figures have been

satisfactorily arranged, they ought to be

carefully

drawn

as to outline. In doing so, take pains to

vary the postures,

giving

them

action, and avoiding the

stiff wooden, fashion-plate

type of person

so

common to architectural drawings.

When the time comes to

render

these

accessories with the pen

(and this ought, by the

way, to be the last

thing

done) do not lose the

freedom and breadth of the

drawing by

dwelling

too long on them. Rise

superior to such details as

the patterns of

neckties.

We

will now consider the

application to architectural subjects of

the

remarks

on technique and color contained in

the previous chapters.

To

learn to render the

different textures of the

materials used in Architectural

architecture,

the student would do well to

examine and study the

Textures

methods

of prominent illustrators, and then

proceed to forget

them,

developing

meanwhile a method of his

own. It will be instructive

for

him,

however, as showing the

opportunity for play of

individuality, to

notice

how very different, for

instance, is Mr. Gregg's manner of

rendering

brick work to that of Mr.

Railton. Compare Figs. 48 and

49.

One

is splendidly broad,--almost

decorative,--the other intimate

and

picturesque.

The work of both these

men is eminently worthy of

study.

For

the sophisticated simplicity and directness of

his method and the

almost

severe conscientiousness of his drawing,

no less than for

his

masterly

knowledge of black and white, no safer

guide could be

commended

to the young architectural

pen-man for the study

of

principles

than Mr. Gregg. Architectural

illustration in America owes

much

to his influence and,

indeed, he may be said to

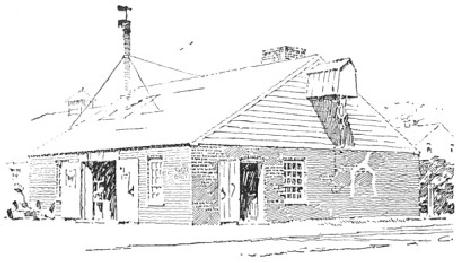

have furnished it

with

a grammar. Take his drawing

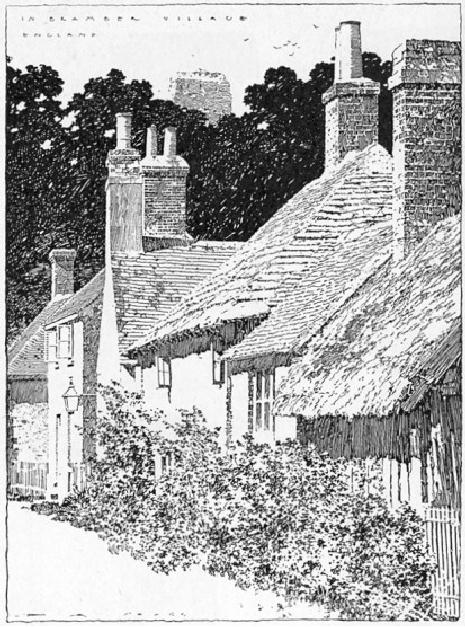

of the English cottages, Fig.

50. It is a

masterly

piece of pen work. There is

not a feeble or tentative

stroke in

the

whole of it. The color is

brilliant and the textures

are expressed with

wonderful

skill. The student ought to

carefully observe the rendering

of

the

various roofs. Notice how

the character of the thatch

on the second

cottage

differs from that on the

first, and how radically the

method of

rendering

of either varies from that

used on the shingle roof at

the end of

the

picture. Compare also the two gable

chimneys with each other

as

well

as with the old ruin

seen over the tree-tops.

Here is a drawing by an

architectural

draughtsman of an architectural actuality

and

not of an

artificial

abstraction. This is a fairer

ground on which to meet

the

illustrators

of the picturesque.

FIG.

48

D.

A. GREGG

FIG.

49

HERBERT

RAILTON

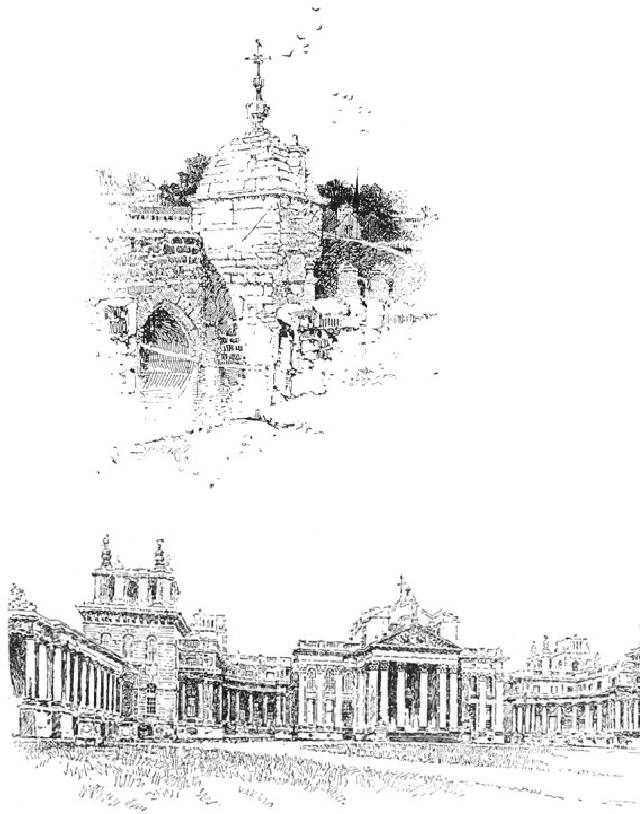

FIG.

50

D.

A. GREGG

FIG.

51

WALTER

M. CAMPBELL

FIG.

52

HERBERT

RAILTON

FIG.

53

FIG.

54

C.

F. BRAGDON

FIG.

55

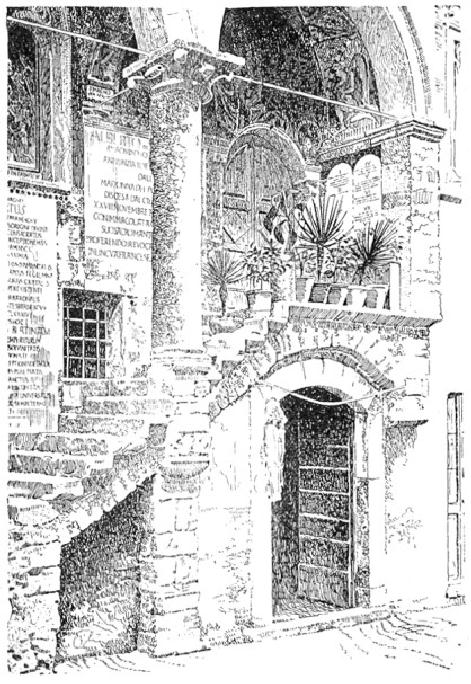

Mr.

Campbell's drawing, Fig. 51,

is a very good example of the

Examples

rendering

of stone textures. The old

masonry is capitally expressed

by

the

short irregular line. The

student is advised to select some portion

of

this,

as well as of the preceding

example to copy, using, no

matter how

small

the drawings he may make, a pen

not smaller than number

303. I

know

of no architectural illustrator who

hits stonework off quite

so

cleverly

as Mr. Goodhue. Notice, in his

drawing of the masonry, in

Fig.

8,

how the stones are

picked out and rendered

individually in places and

how

this intimate treatment is

confined to the top of the

tower where it

tells

against the textures of the

various roofs and how it is

then merged in

a

broad gray tone which is

carried to the street. Mr. Railton's

sketches are

full

of clever suggestion for the

architectural illustrator in the

way of

texture.

Figs. 7 and 52 show his free

rendering of masonry. The

latter is

an

especially very good subject

for study. Observe how

well the texture

tells

in the high portion of the

abutment by reason of the

thick, broken

lines.

For a distant effect of stone

texture, the drawing by Mr.

Jaccaci,

Fig.

53, is a fine example. In

this the rendering is

confined merely to

the

organic

lines of the architecture, and

yet the texture is capitally

expressed

by

the quality of the stroke,

which is loose and much

broken. The

general

result is extremely crisp

and pleasing. For broad

rendering of

brick

textures, perhaps there is no one

who shows such a

masterly

method

as Mr. Gregg. As may be seen in

his sketch of the

blacksmith

shop,

Fig. 48, he employs an

irregular dragging line with

a great deal of

feeling.

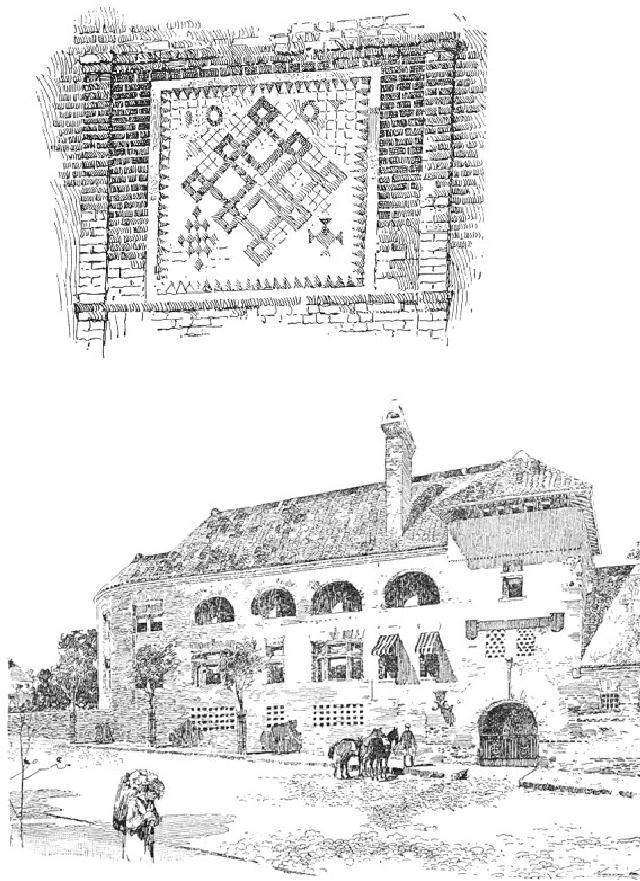

The brick panel by Mr.

Bragdon, Fig. 54, is a neat

piece of work.

There

is excellent texture, too, in

the picturesque drawing by Mr.

Harvey

Ellis,

Fig. 55:--observe the

rendering of the rough brick

surface at the

left

side of the building. A more

intimate treatment is that

illustrated in

the

detail by Mr. C. E. Mallows, the

English draughts man, Fig.

56. In

this

drawing, however, the edges

of the building are

unpleasantly hard,

and

are somewhat out of

character with the quaint

rendering of the

surfaces.

Mr. Goodhue uses a similar

treatment, and, I think,

rather more

successfully.

On the whole, the broader

method, where the texture

is

carried

out more uniformly, is more

to be commended, at least for

the

study

of the beginner. Some

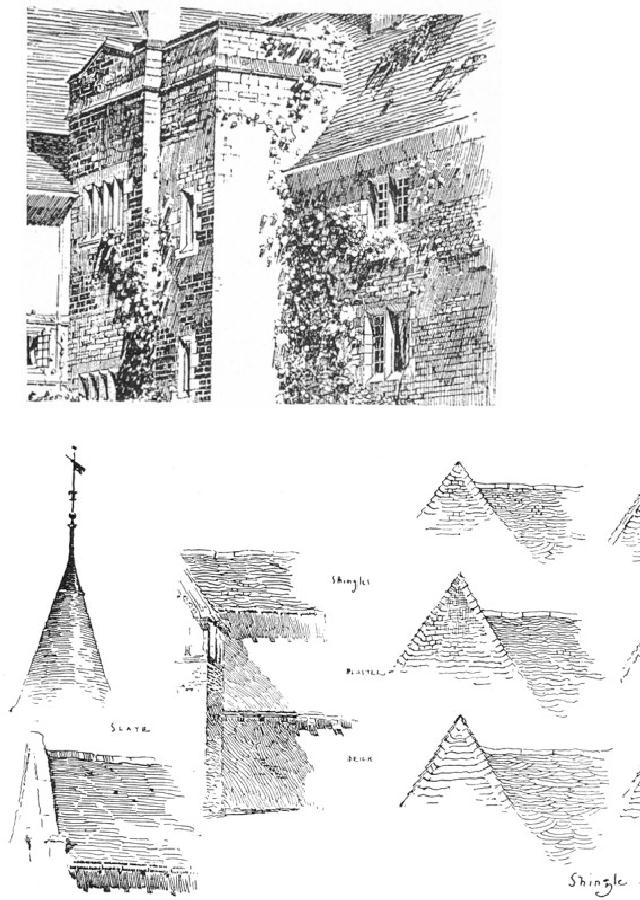

examples of shingle and slate

textures are

illustrated

by Fig. 57. It is advisable to

employ a larger pen for

the

shingle,

so as to ensure the requisite coarseness

of effect.

FIG.

56

C.

E. MALLOWS

FIG.

57

FIG.

58

C.

D. M.

To

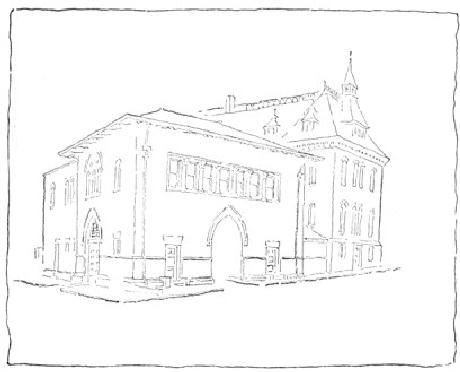

favorably illustrate an architectural

subject it will be found An

generally

expedient to give prominence to one

particular elevation in the

Architectural

perspective,

the other being permitted to

vanish sharply. Fig. 58 may

be Problem

said

to be a fairly typical problem

for the architectural

penman. The old

building

on the right, it must be

understood, is not a mere accessory,

but

is

an essential part of the picture.

The matter of surroundings is

the first

we

have to decide upon, and

these ought always to be

disposed with

reference

to the particular form of

composition which the

subject may

suggest.

Were we dealing with the

foreground building alone

there

would

be no difficulty in adjusting the

oval or the diamond form

of

composition

to it.* As it is, the

difficulty lies in the long

crested roof-line

which

takes the same oblique

angle as the line of the

street, and the

influence

of this line must be, as

far as possible, counteracted. Now

the

heavy

over-hang of the principal

roof will naturally cast a

shadow which

will

be an important line in the

composition, so we arrange our

accessories

at the right of the picture

in reference to this. Observe

that

the

line of the eaves, if

continued, would intersect

the top of the gable

chimney.

The dwelling and the tree

then form a focus for

the converging

lines

of sidewalk and roof, thus

qualifying the vertical

effect of the

building

on the right. As the

obliquity of the composition is

still

objectionable,

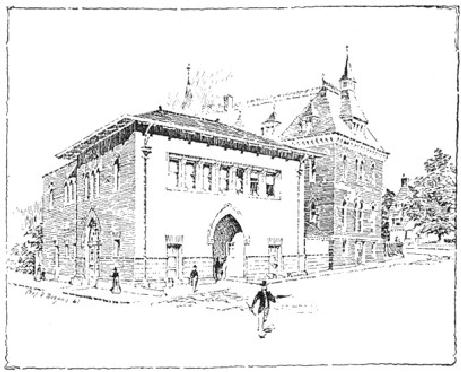

we decide to introduce a foreground

figure which will

break

up the line of the long

sidewalk, and place it so that it will

increase

the

influence of some contrary

line, see Fig. 59. We

find that by putting

it

a little to the right of the

entrance and on a line with

that of the left

sidewalk,

the picture is pleasingly

balanced.

[Footnote

*: See footnote on page

62.]

FIG.

59

C.

D. M.

We

are now ready to consider

the disposition of the

values. As I have

said

before, these are determined

by the scheme of light and

shade. For

this

reason any given subject

may be variously treated. We do

not

necessarily

seek the scheme which will

make the most pictorial

effect,

however,

but the one which will serve to

set off the building to

the best

advantage.

It is apparent that the most

intelligible idea of the

form of the

structure

will be given by shading one side; and,

as the front is the

more

important

and the more interesting

elevation, on which we need

sunlight

to

give expression to the

composition, it is natural to shade

the other,

thus

affording a foil for the

bright effects on the front.

This bright effect

will

be further enhanced if we assume that

the local color of the

roof is

darker

than that of the walls, so

that we can give it a gray

tone, which

will

also make the main building stand

away from the other. If,

however,

we

were to likewise assume that

the roof of the other

building were

darker

than its walls, we should be

obliged to emphasize the

objectionable

roof line, and as, in any

case, we want a dark effect

lower

down

on the walls to give relief

to our main building, we will

assume

that

the local color of the

older walls is darker than

that of the new.

The

shadow

of the main cornice we will make

quite strong, emphasis

being

placed

on the nearer corner, which is

made almost black. This

color is

repeated

in the windows, which,

coming as they do in a group,

are some

of

them more filled in than

others, to avoid an effect of

monotony. The

strong

note of the drawing is then

given by the foreground

figure.