|

VALUES |

| << TECHNIQUE |

| PRACTICAL PROBLEMS >> |

rough

sheet of paper, to remove any

superfluous ink. If the

spattering is

well

done, it gives a very

delicate tone of interesting

texture, but if not

cleverly

employed, and especially if there be a

large area of it, it is

very

likely to

look out of character with

the line portions of the

drawing.

A

method sometimes employed to give a

soft black effect is to

moisten

the

lobe of the thumb lightly

with ink and press it

upon the paper. The

series

of lines of the skin make an

impression that can be reproduced

by

the

ordinary line processes. As in

the case of spatter work,

superfluous

ink

must be looked after before

making the impression so as to

avoid

leaving

hard edges. Thumb markings

lend themselves to the

rendering of

dark

smoke, and the like, where

the edges require to be soft

and vague,

and

the free direction of the

lines impart a feeling of

movement.

Interesting

effects of texture are sometimes

introduced into pen

drawings

by obtaining the impression of a canvas

grain. To produce

this,

it

is necessary that the

drawing be made on fairly

thin paper. The modus

operandi

is

as follows: Place the

drawing over a piece of

mounted

canvas

of the desired coarseness of

grain, and, holding it

firmly, rub a

lithographic

crayon vigorously over the

surface of the paper. The

grain

of

the canvas will be found to be clearly

reproduced, and, as the

crayon

is

absolutely black, the effect

is capable of reproduction by the

ordinary

photographic

processes.

CHAPTER

IV

VALUES

After

the subject has been

mapped out in pencil, and

before beginning The

Color

the

pen work, we have to consider

and determine the proper

disposition Scheme

of

the Color. By "color" is

meant, in this connection,

the gamut of values

from

black to white, as indicated in

Fig. 23. The success or

failure of the

drawing

will largely depend upon the

disposition of these elements,

the

quality

of the technique being a

matter of secondary concern. Beauty

of

line

and texture will not redeem

a drawing in which the

values are badly

disposed,

for upon them we depend

for the effect of unity, or

the

pictorial

quality. If the values are

scattered or patchy the

drawing will not

focus

to any central point of

interest, and there will be no unity in

the

result.

There

are certain general laws by

which color may be

pleasingly

disposed,

but it must be borne in mind

that it ought to be

disposed

naturally

as well. By a "natural" scheme of

color, I mean one which is

consistent

with a natural effect of

light and shade. Now the

gradation

from

black to white, for example,

is a pleasing scheme, as may be

observed

in Fig. 24, yet the

effect is unnatural, since the

sky is black. In

a

purely decorative illustration

like this, however, such

logic need not be

considered.

Since,

as I said before,

Principality

color

is the factor which

in

the Color-

makes

for the unity of

the

Scheme

result,

the first principle

to

be

regarded

in

its

arrangement

is that of

Principality,--there

must be

some

dominant note in the

rendering.

There should not,

for

instance, be two

principal

dark

spots of equal value

in

the

same drawing, nor

two

equally

prominent areas of

white.

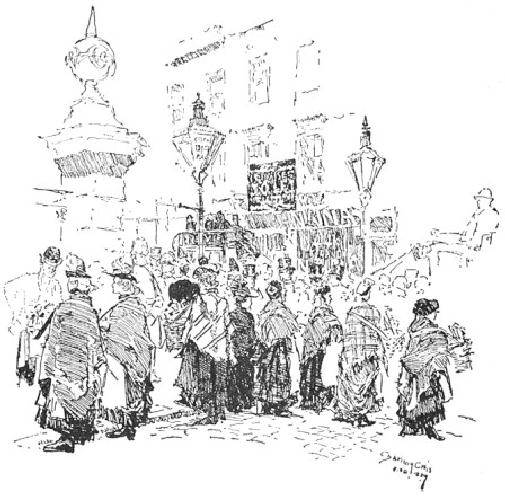

The Vierge drawing, FIG. 24

D.

A. GREGG

FIG.

23 C. D. M.

Fig.

25, and that by Mr. Pennell,

Fig. 5, are no

exceptions

to

this rule; the black

figure of the old man

counting as one note in

the

former,

as do the dark arches of the

bridge in the latter. The

work of both

these

artists is eminently worthy of

study for the knowing

manner in

which

they dispose their

values.

FIG.

25

DANIEL

VIERGE

The

next thing to be sought is

Variety. Too obvious or

positive a Variety

scheme,

while possibly not

unsuitable for a conventional

decorative

drawing,

may not be well adapted to a

perspective subject. The

large

color

areas should be echoed by

smaller ones throughout the

picture.

Take,

for example, the Vierge

drawing shown in Fig. 26.

Observe how

the

mass of shadow is relieved by

the two light holes

seen through the

inn

door. Without this

repetition of the white the

drawing would lose

much

of its character. In Rico's

drawing, Fig. 11, a tiny

white spot in the

shadow

cast over the street would,

I venture to think, be

helpful,

beautifully

clear as it is; and the

black area at the end of the

wall seems a

defect

as it competes in value with

the dark figure.

FIG.

26

DANIEL

VIERGE

Lastly,

Breadth of Effect has to be considered.

It is requisite that, Breadth

of

however

numerous the tones are (and

they should not be too

numerous), Effect

the

general effect should be

simple and homogeneous. The

color must

count

together broadly, and not be

cut up into patches.

FIG.

27

HARRY

FENN

It

is important to remember that

the gamut from black to

white is a

short

one for the pen. One

need only try to faithfully

render the high

lights

of an ordinary table glass

set against a gray background, to

be

assured

of its limitations in this

respect. To represent even

approximately

the

subtle values would require

so much ink that nothing

short of a

positively

black background would

suffice to give a semblance of

the

delicate

transparent effect of the

glass as a whole. The gray

background

would,

therefore, be lost, and if a really

black object were also part

of the

picture

it could not be represented at

all. Observe, in Fig. 27,

how just

such

a problem has been worked

out by Mr. Harry

Fenn.

It

will be manifest that the

student must learn to think

of things in their

broad

relation. To be specific,--in the

example just considered, in

order

to

introduce a black object the

scheme of color would have

needed

broadening

so that the gray background

could be given its proper

value,

thus

demanding that the elaborate

values of the glass be

ignored, and just

enough

suggested to give the

general effect. This

reasoning would

equally

apply were the light

object, instead of a glass, something

of

intricate

design, presenting positive shadows.

Just so much of such

a

design

should be rendered as not to darken

the object below its

proper

relative

value as a whole. In this

faculty of suggesting things

without

literally

rendering them consists the

subtlety of pen drawing.

It

may be said, therefore, that

large light areas resulting

from the

necessary

elimination of values are

characteristic of pen drawing.

The

degree

of such elimination depends, of course,

upon the character of

the

subject,

this being entirely a matter

of relation. The more black

there is in

a

drawing the greater the

number of values that can be

represented.

Generally

speaking, three or four are

all that can be managed, and

the

beginner

had better get along

with three,--black, half-tone, and

white.

FIG.

28

REGINALD

BIRCH

While

it is true that every

subject is likely to contain

some motive or Various

suggestion

for its appropriate color-scheme, it

still holds that, many

Color-

times,

and especially in those cases where

the introduction of foreground

Schemes

features

at considerable scale is necessary

for the interest of the

picture,

an

artificial arrangement has to be devised.

It is well, therefore, to be

acquainted

with the possibilities of

certain color combinations.

The most

brilliant

effect in black and white

drawing is that obtained by

placing the

prominent

black against a white area

surrounded by gray. The

white

shows

whiter because of the gray

around it, so that the

contrast of the

black

against it is extremely vigorous and

telling. This may be said to

be

the

illustrator's tour

de force. We have

it illustrated by Mr. Reginald

Birch's

drawing, Fig. 28. Observe

how the contrast of black

and white is

framed

in by the gray made up of

the sky, the left

side of the building,

the

horse, and the knight. In

the drawing by Mr. Pennell,

Fig. 29, we

have

the same scheme of color.

Notice how the trees

are darkest just

where

they are required to tell

most strongly against the

white in the

centre

of the picture. An admirable

illustration of the effectiveness of

this

color-scheme

is shown in the "Becket" poster by

the "Beggarstaff

Brothers,"

Fig. 69. Another scheme is

to have the principal black

in the

gray

area, as in the Vierge

drawing, Fig. 26 and in

Rico's sketch, Fig.

11.

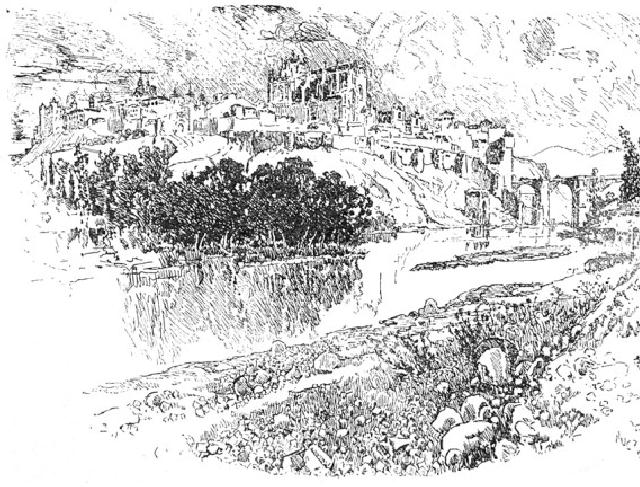

FIG.

29

JOSEPH

FIG.

30

B.

G. GOODHUE

FIG.

31

JOSEPH

PENNELL

Still

another and a more restful

scheme is the actual

gradation of color.

This

gradation, from black to

white, wherein the white

occupies the

centre

of the picture, is to be noted in

Fig. 20. Observe how

the dark side

of

the foreground tree tells against

the light side of the one

beyond,

which,

in its turn, is yet so

strongly shaded as to count

brilliantly against

the

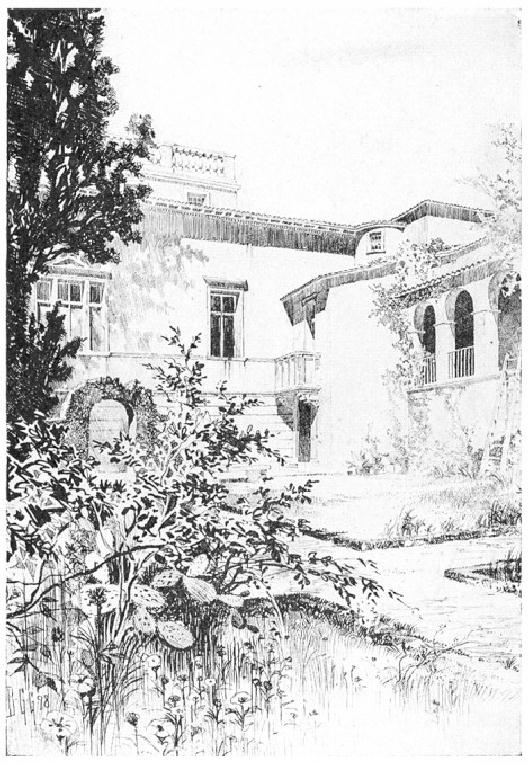

white building. Still again,

in Mr. Goodhue's drawing, Fig.

30, note

how

the transition from the

black tree on the left to

the white building is

pleasingly

softened by the gray shadow.

Notice, too, how the

brilliancy

of

the drawing is heightened by

the gradual emphasis on the

shadows

and

the openings as they approach

the centre of the picture.

Yet another

example

of this color-scheme is the

drawing by Mr. Gregg, Fig.

50. The

gradation

here is from the top of the

picture downwards. The

sketch of

the

coster women by Mr. Pennell, Fig.

31, shows this gradation

reversed.

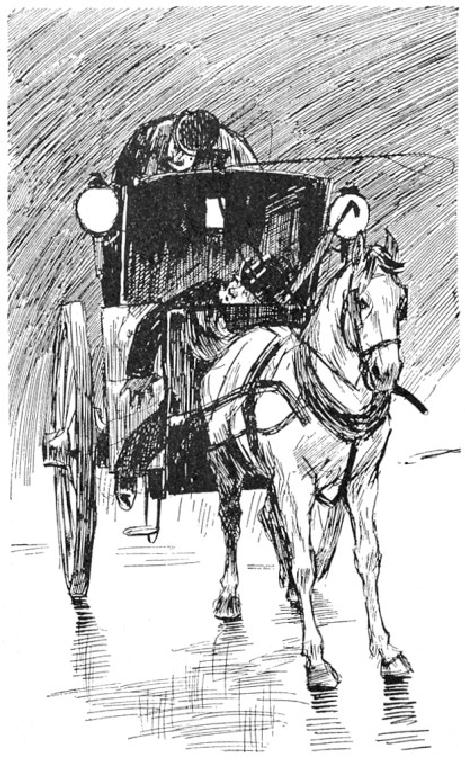

The

drawing of the hansom cab,

Fig. 32, by Mr. Raven Hill,

illustrates

a

very strong color-scheme,--gray and

white separated by black,

the

gray

moderating the black on the

upper side, leaving it to

tell strongly

against

the white below. Notice

how luminous is this same

relation of

color

where it occurs in the

Venetian subject by Rico,

Fig. 14. The

shadow

on the water qualifies the

blackness of the gondola

below,

permitting

a brilliant contrast with

the white walls of the

building above.

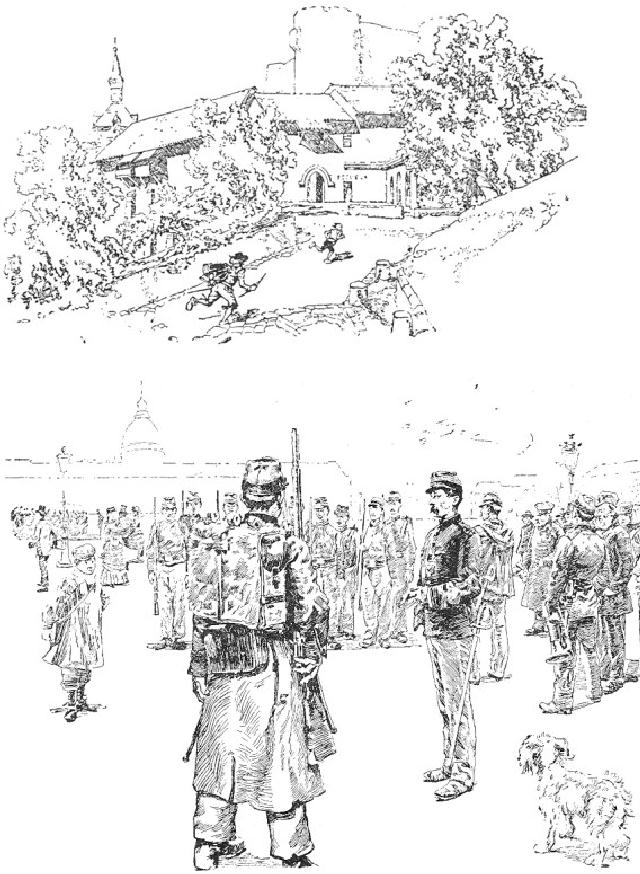

It

is interesting to observe how Vierge and

Pennell, but chiefly

the

former,

very often depend for

their grays merely upon

the delicate tone

resulting

from the rendering of form

and of direct shadow,

without any

local

color. This may be seen in

the Vierge drawing, Fig.

33. Observe in

this,

as a consequence, how brilliantly the

tiny black counts in the

little

figure

in the centre. Notice, too,

in the drawing of the

soldiers by

Jeanniot,

Fig. 34, that there is

very little black; and yet

see how brilliant

is

the effect, owing largely to

the figures being permitted

to stand out

against

a white ground in which

nothing is indicated but the

sky-line of

the

large building in the

distance.

FIG.

32

L.

RAVEN HILL

FIG.

33

DANIEL

VIERGE

FIG.

34