|

CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS |

| << THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS |

| OLD INNS >> |

CHAPTER

IX

CATHEDRAL

CITIES AND ABBEY

TOWNS

There is

always an air of quietude and

restfulness about an ordinary

cathedral city.

Some of

our cathedrals are set in

busy places, in great centres of

population,

wherein

the high towering minster

looks down with a kind of

pitying compassion

upon

the toiling folk and invites

them to seek shelter and

peace and the

consolations

of religion in her quiet

courts. For ages she

has watched over the

city

and

seen generation after

generation pass away. Kings

and queens have come to

lay

their

offerings on her altars, and

have been borne there

amid all the pomp of

stately

mourning

to lie in the gorgeous tombs

that grace her choir.

She has seen it all--

times

of pillage and alarm, of robbery and

spoliation, of change and

disturbance,

but

she lives on, ever

calling men with her

quiet voice to look up in

love and faith

and

prayer.

But

many of our cathedral cities

are quite small places

which owe their very

life

and

existence to the stately

church which pious hands

have raised centuries

ago.

There

age after age the

prayer of faith, the anthems

of praise, and the

divine

services

have been offered.

In

the glow of a summer's

evening its heavenly

architecture stands out, a

mass of

wondrous

beauty, telling of the skill

of the masons and craftsmen of

olden days

who

put their hearts into their

work and wrought so surely

and so well. The

greensward

of the close, wherein the

rooks caw and guard their

nests, speaks of

peace

and joy that is not of

earth. We walk through the

fretted cloisters that

once

echoed

with the tread of sandalled

monks and saw them

illuminating and

copying

wonderful

missals, antiphonaries, and other

manuscripts which we prize so

highly

now.

The deanery is close at hand, a

venerable house of peace and learning;

and the

canons'

houses tell of centuries of

devoted service to God's Church,

wherein many

a

distinguished scholar, able preacher, and

learned writer has lived and

sent forth

his

burning message to the

world, and now lies at peace

in the quiet minster.

The

fabric of the cathedrals is often in

danger of becoming part and parcel

of

vanishing

England. Every one has

watched with anxiety the

gallant efforts that

have

been made to save

Winchester. The insecure

foundations, based on

timbers

that

had rotted, threatened to bring down

that wondrous pile of

masonry. And now

Canterbury

is in danger.

The

Dean and Chapter of Canterbury having

recently completed the

reparation of

the

central tower of the

cathedral, now find

themselves confronted

with

responsibilities

which require still heavier

expenditure. It has recently

been found

that

the upper parts of the two

western towers are in a dangerous

condition. All the

pinnacles

of these towers have had to be

partially removed in order to

avoid the risk

of

dangerous injury from falling stones, and

a great part of the external

work of the

two

towers is in a state of grievous

decay.

The

Chapter were warned by the

architect that they would

incur an anxious

responsibility

if they did not at once adopt

measures to obviate this

danger.

Further,

the architect states that

there are some fissures and

shakes in the

supporting

piers

of the central tower within

the cathedral, and that some

of the stonework

shows

signs of crushing. He further reports

that there is urgent need of

repair to the

nave

windows, the south transept

roof, the Warriors' Chapel,

and several other parts

of

the building. The nave

pinnacles are reported by

him to be in the last stage

of

decay,

large portions falling

frequently, or having to be

removed.

In

these modern days we run

"tubes" and under-ground railways in

close proximity

to

the foundations of historic

buildings, and thereby endanger their

safety. The

grand

cathedral of St. Paul,

London, was threatened by a "tube," and

only saved by

vigorous

protest from having its

foundations jarred and shaken by rumbling

trains

in

the bowels of the earth.

Moreover, by sewers and drains

the earth is made

devoid

of

moisture, and therefore is liable to

crack and crumble, and to disturb

the

foundations

of ponderous buildings. St. Paul's still

causes anxiety on this

account,

and

requires all the care and

vigilance of the skilful

architect who guards

it.

The

old Norman builders loved a

central tower, which they

built low and

squat.

Happily

they built surely and well,

firmly and solidly, as their

successors loved to

pile

course upon course upon their

Norman towers, to raise a

massive

superstructure,

and often crown them

with a lofty, graceful, but

heavy spire. No

wonder

the early masonry has, at

times, protested against this additional

weight,

and

many mighty central towers

and spires have fallen and

brought ruin on the

surrounding

stonework. So it happened at Chichester

and in several other

noble

churches.

St. Alban's tower very

nearly fell. There the

ingenuity of destroyers and

vandals

at the Dissolution had dug a

hole and removed the earth

from under one of

the

piers, hoping that it would

collapse. The old tower

held on for three

hundred

years,

and then the mighty mass

began to give way, and Sir

Gilbert Scott tells

the

story

of its reparation in 1870, of

the triumphs of the skill of

modern builders, and

their

bravery and resolution in saving

the fall of that great

tower. The greatest

credit

is

due to all concerned in that

hazardous and most difficult task. It had

very nearly

gone.

The story of Peterborough, and of

several others, shows that

many of these

vast

fanes which have borne the

storms and frosts of

centuries are by no means

too

secure,

and that the skill of wise

architects and the wealth of

the Englishmen of to-

day

are sorely needed to prevent

them from vanishing. If they

fell, new and modern

work

would scarcely compensate us

for their loss.

We

will take Wells as a model of a cathedral

city which entirely owes its

origin to

the

noble church and palace

built there in early times.

The city is one of the

most

picturesque

in England, situated in the

most delightful country, and

possessing the

most

perfect ecclesiastical buildings which

can be conceived. Jocelyn de

Wells,

who

lived at the beginning of

the thirteenth century

(1206-39), has for many

years

had

the credit of building the

main part of this beautiful

house of God. It is hard to

have

one's beliefs and early

traditions upset, but modern

authorities, with

much

reason,

tell us that we are all

wrong, and that another

Jocelyn--one Reginald

Fitz-

Jocelyn

(1171-91)--was the main

builder of Wells Cathedral.

Old documents

recently

discovered decide the question,

and, moreover, the style of

architecture is

certainly

earlier than the fully

developed Early English of

Jocelyn de Wells. The

latter,

and also Bishop Savaricus (1192-1205),

carried out the work,

but the whole

design

and a considerable part of the building

are due to Bishop Reginald

Fitz-

Jocelyn.

His successors, until the

middle of the fifteenth

century, went on

perfecting

the wondrous shrine, and in

the time of Bishop

Beckington Wells was in

its

full glory. The church, the

outbuildings, the episcopal palace, the

deanery, all

combined

to form a wonderful architectural

triumph, a group of buildings

which

represented

the highest achievement of

English Gothic art.

Since

then many things have

happened. The cathedral, like

all other ecclesiastical

buildings,

has passed through three

great periods of iconoclastic violence. It

was

shorn

of some of its glory at the

Reformation, when it was plundered of

the

treasures

which the piety of many

generations had heaped together. Then

the

beautiful

Lady Chapel in the cloisters

was pulled down, and the

infamous Duke of

Somerset

robbed it of its wealth and meditated

further sacrilege. Amongst

these

desecrators

and despoilers there was a mighty hunger

for lead. "I would that

they

had

found it scalding," exclaimed an

old chaplain of Wells; and to get

hold of the

lead

that covered the roofs--a

valuable commodity--Somerset and

his kind did

much

mischief to many of our cathedrals and

churches. An infamous bishop

of

York,

at this period, stripped his

fine palace that stood on

the north of York

Minster,

"for the sake of the lead

that covered it," and shipped it

off to London,

where

it was sold for �1000;

but of this sum he was

cheated by a noble duke,

and

therefore

gained nothing by his infamy.

During the Civil War it

escaped fairly well,

but

some damage was done,

the palace was despoiled; and at

the Restoration of

the

Monarchy

much repair was needed.

Monmouth's rebels wrought havoc.

They came

to

Wells in no amiable mood,

defaced the statues on the

west front, did

much

wanton

mischief, and would have

caroused about the altar had

not Lord Grey stood

before

it with his sword drawn, and

thus preserved it from the

insults of the

ruffians.

Then came the evils of

"restoration." A terrible renewing was

begun in

1848,

when the old stalls

were destroyed and much

damage done. Twenty

years

later

better things were

accomplished, save that the

grandeur of the west front

was

belittled

by a pipey restoration, when

Irish limestone, with its

harsh hue, was used

to

embellish it.

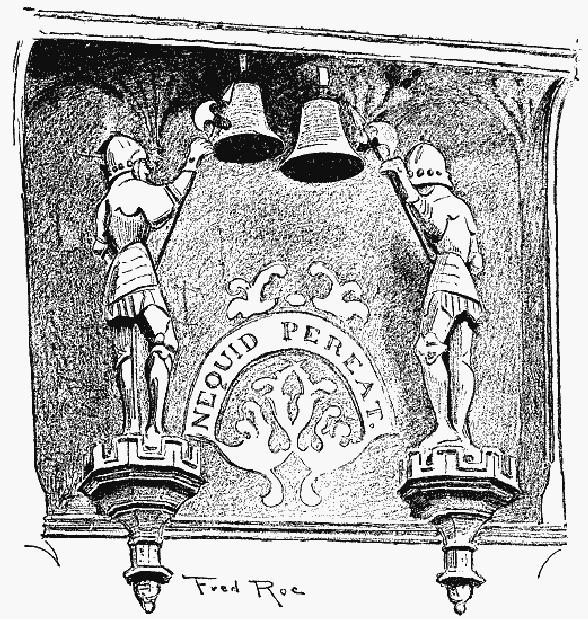

A

curiosity at Wells are the

quarter jacks over the

clock on the exterior north

wall

of

the cathedral. Local

tradition has it that the

clock with its accompanying

figures

was

part of the spoil removed

from Glastonbury Abbey. The

ecclesiastical

authorities

at Wells assert in contradiction to

this that the clock was

the work of one

Peter

Lightfoot, and was placed in the

cathedral in the latter part

of the fourteenth

century.

A minute is said to exist in

the archives of repairs to the

clock and figures

in

1418. It is Mr. Roe's opinion

that the defensive armour on

the quarter jacks

dates

from

the first half of the

fifteenth century, the plain

oviform breastplates and

basinets,

as well as the continuation of

the tassets round the

hips, being very

characteristic

features of this period. The

halberds in the hands of the

figures are

evidently

restorations of a later time. It

may be mentioned that in

1907, when the

quarter

jacks were painted, it was

discovered that though the

figures themselves

were

carved out of solid blocks

of oak hard as iron, the arms

were of elm bolted

and

braced thereon. Though such

instances of combined materials are

common

enough

among antiquities of medieval

times, it may yet be

surmised that the

jar

caused

by incessant striking may in time

have necessitated repairs to the

upper

limbs.

The arms are immovable, as

the figures turn on pivots

to strike.

Quarter

Jacks over the Clock on

exterior of North Wall of

Wells Cathedral.

An

illustration is given of the

palace at Wells, which is one of

the finest examples

of

thirteenth-century houses existing in

England. It was begun by

Jocelyn. The

great

hall, now in ruins, was

built by Bishop Burnell at

the end of the

thirteenth

century,

and was destroyed by Bishop Barlow in

1552. The chapel is

Decorated.

The

gatehouse, with its drawbridge,

moat, and fortifications, was constructed

by

Bishop

Ralph, of Shrewsbury, who

ruled from 1329 to 1363.

The deanery was built

by

Dean Gunthorpe in 1475, who was

chaplain to Edward IV. On the

north is the

beautiful

vicar's close, which has

forty-two houses, constructed mainly by

Bishop

Beckington

(1443-64), with a common

hall erected by Bishop Ralph

in 1340 and a

chapel

by Budwith (1407-64), but

altered a century later. You

can see the

old

fireplace,

the pulpit from which one of

the brethren read aloud

during meals, and an

ancient

painting representing Bishop

Ralph making his grant to

the kneeling

figures,

and some additional figures

painted in the time of Queen

Elizabeth.

The

Gate House, Bishop's Palace,

Wells

When

we study the cathedrals of

England and try to trace the

causes which led to

the

destruction of so much that

was beautiful, so much of

English art that

has

vanished,

we find that there were

three great eras of iconoclasm.

First there were

the

changes wrought at the time

of the Reformation, when a rapacious

king and his

greedy

ministers set themselves to

wring from the treasures of

the Church as much

gain

and spoil as they were able.

These men were guilty of the

most daring acts of

shameless

sacrilege, the grossest robbery.

With them nothing was

sacred. Buildings

consecrated

to God, holy vessels used in

His service, all the

works of sacred art,

the

offerings

of countless pious benefactors were

deemed as mere profane things to

be

seized

and polluted by their sacrilegious

hands. The land was full of

the most

beautiful

gems of architectural art,

the monastic churches. We can

tell something of

their

glories from those which

were happily spared and

converted into cathderals or

parish

churches. Ely, Peterborough

the pride of the Fenlands,

Chester, Gloucester,

Bristol,

Westminster, St. Albans,

Beverley, and some others

proclaim the grandeur

of

hundreds of other magnificent

structures which have been

shorn of their leaden

roofs,

used as quarries for

building-stone, entirely removed and

obliterated, or left

as

pitiable ruins which still

look beautiful in their

decay. Reading,

Tintern,

Glastonbury,

Fountains, and a host of others

all tell the same

story of pitiless

iconoclasm.

And what became of the

contents of these churches?

The contents

usually

went with the fabric to

the spoliators. The halls of

country-houses were

hung

with altar-cloths; tables and beds

were quilted with copes;

knights and squires

drank

their claret out of chalices

and watered their horses in

marble coffins. From

the

accounts of the royal jewels

it is evident that a great deal of Church

plate was

delivered

to the king for his

own use, besides which

the sum of �30,360

derived

from

plate obtained by the

spoilers was given to the

proper hand of the

king.

The

iconoclasts vented their

rage in the destruction of stained

glass and beautiful

illuminated

manuscripts, priceless tomes and costly

treasures of exceeding rarity.

Parish

churches were plundered

everywhere. Robbery was in the

air, and clergy and

churchwardens

sold sacred vessels and appropriated

the money for

parochial

purposes

rather than they should be

seized by the king.

Commissioners were sent to

visit

all the cathedral and parish

churches and seize the

superfluous ornaments

for

the

king's use. Tithes, lands,

farms, buildings belonging to

the church all went

the

same

way, until the hand of

the iconoclast was stayed, as there was

little left to steal

or

to be destroyed. The next

era of iconoclastic zeal was

that of the Civil War

and

the

Cromwellian period. At Rochester

the soldiers profaned the

cathedral by using

it

as a stable and a tippling place, while

saw-pits were made in the

sacred building

and

carpenters plied their trade. At

Chichester the pikes of the

Puritans and their

wild

savagery reduced the interior to a

ruinous desolation. The

usual scenes of mad

iconoclasm

were enacted--stained glass

windows broken, altars

thrown down, lead

stripped

from the roof, brasses and

effigies defaced and broken. A

creature named

"Blue

Dick" was the wild leader of

this savage crew of

spoliators who left little

but

the

bare walls and a mass of

broken fragments strewing

the pavement. We need

not

record

similar scenes which took

place almost everywhere.

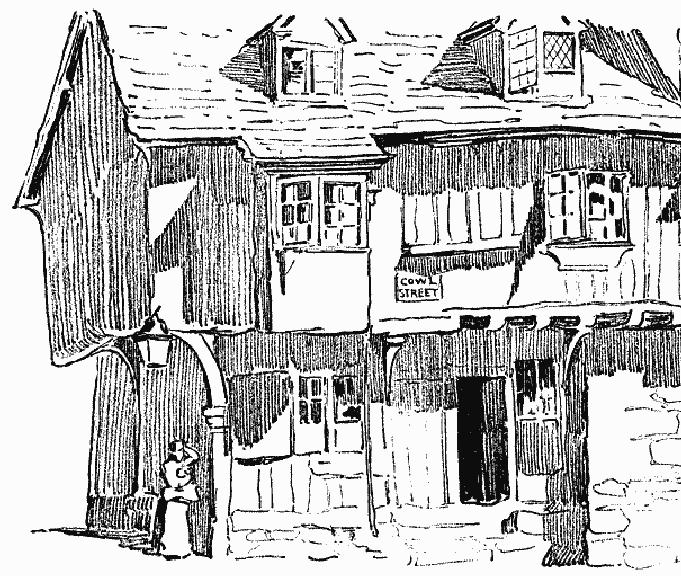

House

in which Bishop Hooper was

imprisoned, Westgate Street,

Gloucester

The

last and grievous rule of

iconoclasm set in with the

restorers, who worked

their

will

upon the fabric of our

cathedrals and churches and did so much

to obliterate all

the

fragments of good architectural work

which the Cromwellian

soldiers and the

spoliators

at the time of the

Reformation had left. The

memory of Wyatt and

his

imitators

is not revered when we see

the results of their work on

our ecclesiastical

fabrics,

and we need not wonder that

so much of English art has

vanished.

The

cathedral of Bristol suffered

from other causes. The

darkest spot in the history

of

the city is the story of

the Reform riots of 1831,

sometimes called "the

Bristol

Revolution,"

when the dregs of the

population pillaged and plundered,

burnt the

bishop's

palace, and were guilty of the

most atrocious

vandalism.

The

"Stone House," Rye,

Sussex

The

city of Bath, once the rival

of Wells--the contention between

the monks of St.

Peter

and the canons of St. Andrews at

Wells being hot and

fierce--has many

attractions.

Its minster, rebuilt by

Bishop Oliver King of Wells

(1495-1503), and

restored

in the seventeenth century, and also in

modern times, is not a

very

interesting

building, though it lacks

not some striking features,

and certainly

contains

some fine tombs and

monuments of the fashionable

folk who flocked to

Bath

in the days of its splendour.

The city itself abounds in

interest. It is a gem of

Georgian

art, with a complete homogeneous

architectural character of its

own

which

makes it singular and unique. It is full

of memories of the great folks

who

thronged

its streets, attended the Bath and

Pump Room, and listened to sermons

in

the

Octagon. It tells of the

autocracy of Beau Nash, of Goldsmith,

Sheridan, David

Garrick,

of the "First Gentleman of

Europe," and many others

who made Bath

famous.

And now it is likely that

this unique little city

with its memories and

its

charming

architectural features is to be mutilated

for purely commercial

reasons.

Every

one knows Bath Street with

its colonnaded loggias on

each side terminated

with

a crescent at each end, and leading to

the Cross Bath in the

centre of the

eastern

crescent. That the original

founders of Bath Street regarded it as

an

important

architectural feature of the

city is evident from the

inscription in

abbreviated

Latin which was engraved on

the first stone of the street

when laid:--

PRO

VRBIS

DIG: ET AMP:

H�C

PON: CVRAV:

SC:

DELEGATI

A:

D: MDCCXCI.

I:

HORTON, PRAET:

T:

BALDWIN, ARCHITECTO.

which

may be read to the effect

that "for the dignity and

enlargement (of the

city)

the

delegates I. Horton, Mayor, and T.

Baldwin, architect, laid

this (stone) A.D.

1791."

It

is actually proposed by the

new proprietors of the Grand

Pump Hotel to

entirely

destroy

the beauty of this street by

removing the colonnaded

loggia on one side of

this

street and constructing a new

side to the hotel two or

three storeys higher,

and

thus

to change the whole character of

the street and practically

destroy it. It is a

sad

pity,

and we should have hoped that

the city Council would

have resisted very

strongly

the proposal that the

proprietors of the hotel

have made to their body.

But

we

hear that the Council is

lukewarm in its opposition to

the scheme, and has

indeed

officially approved it. It is

astonishing what city and

borough councils will

do,

and this Bath Council has

"the discredit of having,

for purely commercial

reasons,

made the first move

towards the destruction

architecturally of the

peculiar

charm

of their unique and beautiful

city."42

Evesham

is entirely a monastic town. It sprang up

under the sheltering walls

of the

famous

abbey--

A

pretty burgh and such as

Fancy loves

For

bygone grandeurs.

This

abbey shared the fate of

many others which we have

mentioned. The Dean of

Gloucester

thus muses over the

"Vanished Abbey":--

"The

stranger who knows nothing

of its story would surely

smile if he

were

told that beneath the grass

and daisies round him were

hidden the

vast

foundation storeys of one of the

mightiest of our proud

medi�val

abbeys;

that on the spot where he

was standing were once

grouped a

forest

of tall columns bearing up

lofty fretted roofs; that

all around

once

were altars all agleam with

colour and with gold; that

besides the

many

altars were once grouped in

that sacred spot chauntries

and

tombs,

many of them marvels of

grace and beauty, placed there in

the

memory

of men great in the service of

Church and State--of

men

whose

names were household words

in the England of our

fathers; that

close

to him were once stately

cloisters, great monastic

buildings,

including

refectories, dormitories, chapter-house,

chapels, infirmary,

granaries,

kitchens--all the varied

piles of buildings which

used to

make

up the hive of a great

monastery."

It

was commenced by Bishop Egwin, of

Worcester, in 702 A.D., but

the era of its

great

prosperity set in after the

battle of Evesham when Simon

de Montford was

slain,

and his body buried in the

monastic church. There was

his shrine to which

was

great pilgrimage, crowds flocking to

lay their offerings there;

and riches

poured

into the treasury of the

monks, who made great

additions to their house, and

reared

noble buildings. Little is

left of its former grandeur.

You can discover part of

the

piers of the great central tower,

the cloister arch of Decorated

work of great

beauty

erected in 1317, and the

abbey fishponds. The bell

tower is one of the

glories

of Evesham. It was built by the

last abbot, Abbot Lichfield, and

was not

quite

completed before the

destruction of the great abbey church

adjacent to it. It is

a

grand specimen of Perpendicular

architecture.

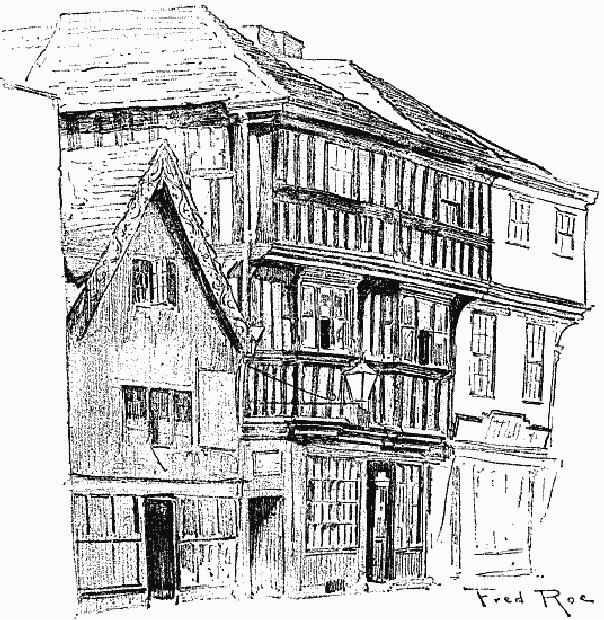

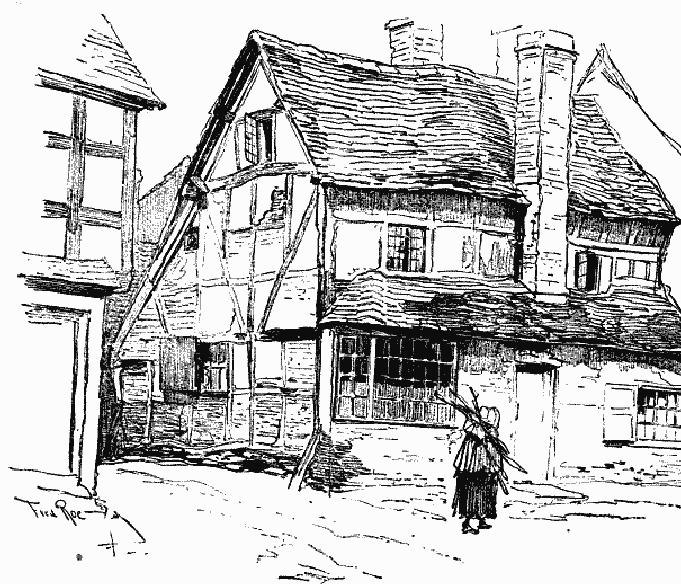

Fifteenth-century

House, Market Place,

Evesham

At

the corner of the Market

Place there is a picturesque

old house with gable and

carved

barge-boards and timber-framed arch, and

we see the old Norman

gateway

named

Abbot Reginald's Gateway,

after the name of its

builder, who also

erected

part

of the wall enclosing the

monastic buildings. A timber-framed

structure now

stretches

across the arcade, but a

recent restoration has

exposed the Norman

columns

which support the arch.

The Church House, always an

interesting building

in

old towns and villages,

wherein church ales and

semi-ecclesiastical functions

took

place, has been restored. Passing

under the arch we see

the two churches in

one

churchyard--All Saints and St.

Laurence. The former has

some Norman work

at

the inner door of the

porch, but its main

construction is Decorated and

Perpendicular.

Its most interesting feature

is the Lichfield Chapel,

erected by the

last

abbot, whose initials and the arms of

the abbey appear on escutcheons on

the

roof.

The fan-tracery roof is

especially noticeable, and the good

modern glass. The

church

of St. Laurence is entirely

Perpendicular, and the chantry of

Abbot

Lichneld,

with its fan-tracery

vaulting, is a gem of English

architecture.

Fifteenth-century

House, Market Place,

Evesham

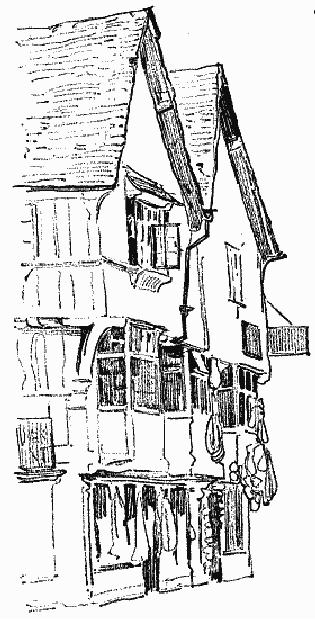

Fifteenth-century

House in Cowl Street,

Evesham

Amongst

the remains of the abbey

buildings may be seen the

Almonry, the

residence

of the almoner, formerly

used as a gaol. An interesting stone

lantern of

fifteenth-century

work is preserved here. Another abbey

gateway is near at hand,

but

little evidence remains of

its former Gothic work. Part

of the old wall built

by

Abbot

William de Chyryton early in

the fourteenth century

remains. In the town

there

is a much-modernized town hall, and near

it the old-fashioned Booth

Hall, a

half-timbered

building, now used as shops

and cottages, where formerly

courts

were

held, including the court of

pie-powder, the usual

accompaniment of every

fair.

Bridge Street is one of the most

attractive streets in the

borough, with its

quaint

old house, and the famous

inn, "The Crown." The

old house in Cowl Street

was

formerly the White Hart

Inn, which tells a curious

Elizabethan story about

"the

Fool

and the Ice," an incident

supposed to be referred to by Shakespeare

in Troilus

and

Cressida (Act

iii. sc. 3): "The

fool slides o'er the ice that

you should break."

The

Queen Anne house in the High

Street, with its

wrought-iron railings and

brackets,

called Dresden House and Almswood, one of

the oldest

dwelling-houses

in

the town, are worthy of

notice by the students of

domestic architecture.

Half-timber

House, Alcester,

Warwick

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION