|

OLD MANSIONS |

| << VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES |

| THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS >> |

was

building the tower and fell

and was killed. Both tower and

effigy are of the

same

period--Early English--and it is quite

possible that the figure may

be that of

the

founder of the tower, but

its head-dress seems to show

that it represents a

lady.

Whipping-posts

and stocks are too light a

punishment for such

vandalism.

The

story of our vanished and

vanishing churches, and of

their vanished and

vanishing

contents, is indeed a sorry one.

Many efforts are made in

these days to

educate

the public taste, to instil

into the minds of their

custodians a due

appreciation

of their beauties and of the

principles of English art and

architecture,

and

to save and protect the treasures

that remain. That these

may be crowned with

success

is the earnest hope and endeavour of

every right-minded

Englishman.

Reversed

Rose carved on "Miserere" in

Norwich Cathedral

CHAPTER

VII

OLD

MANSIONS

One

of the most deplorable

features of vanishing England is

the gradual

disappearance

of its grand old

manor-houses and mansions. A vast

number still

remain,

we are thankful to say. We

have still left to us Haddon

and Wilton,

Broughton,

Penshurst, Hardwick, Welbeck,

Bramshill, Longleat, and a host

of

others;

but every year sees a

diminution in their number.

The great enemy they

have

to contend with is fire, and

modern conveniences and luxuries,

electric

lighting

and the heating apparatus, have

added considerably to their

danger. The old

floors

and beams are unaccustomed to

these insidious wires that

have a habit of

fusing,

hence we often read in the newspapers:

"DISASTROUS FIRE--HISTORIC

MANSION

ENTIRELY DESTROYED." Too often

not only is the house

destroyed,

but most of its valuable

contents is devoured by the

flames. Priceless

pictures

by Lely and Vandyke,

miniatures of Cosway, old

furniture of Chippendale

and

Sheraton, and the countless

treasures which generations of cultured

folk with

ample

wealth have accumulated,

deeds, documents and old

papers that throw

valuable

light on the manners and

customs of our forefathers and on

the history of

the

country, all disappear and can

never be replaced. A great writer has

likened an

old

house to a human heart with a

life of its own, full of sad

and sweet

reminiscences.

It is deplorably sad when

the old mansion disappears

in a night, and

to

find in the morning nothing

but blackened walls--a grim

ruin.

Our

forefathers were a hardy race, and

did not require hot-water

pipes and furnaces

to

keep them warm. Moreover,

they built their houses so

surely and so well

that

they

scarcely needed these modern

appliances. They constructed them

with a great

square

courtyard, so that the rooms

on the inside of the

quadrangle were

protected

from

the winds. They sang

truly in those days, as in

these:--

Sing

heigh ho for the wind and

the rain,

For

the rain it raineth every

day.

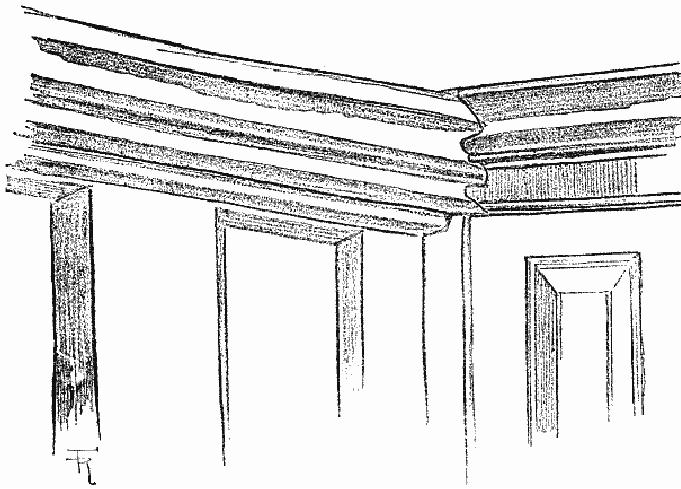

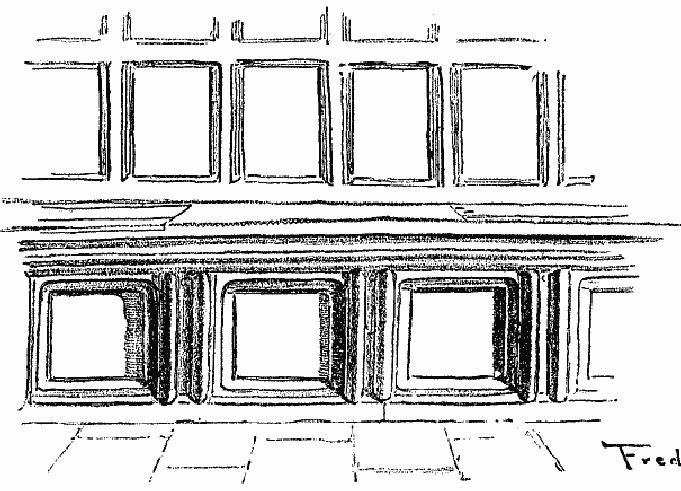

Oak

Panelling. Wainscot of Fifteenth

Century, with addition

circa

late

Seventeenth

Century,

fitted on to it in angle of room in

the Church House, Goudhurst,

Kent

So

they sheltered themselves

from the wind and rain by

having a courtyard or by

making

an E or H shaped plan for

their dwelling-place. Moreover,

they made their

walls

very thick in order that

the winds should not

blow or the rain beat

through

them.

Their rooms, too, were

panelled or hung with

tapestry--famous things

for

making

a room warm and cosy. We

have plaster walls covered

with an elegant wall

-paper

which has always a cold

surface, hence the air in

the room, heated by

the

fire,

is chilled when it comes

into contact with the

cold wall and creates

draughts.

But

oak panelling or woollen tapestry soon

becomes warm, and gives back

its heat

to

the room, making it

delightfully comfortable and

cosy.

One

foolish thing our

forefathers did, and that was to

allow the great beams

that

help

to support the upper floor

to go through the chimney.

How many houses

have

been

burnt down owing to that

fatal beam! But our

ancestors were content with

a

dog-grate

and wood fires; they could

not foresee the advent of

the modern range

and

the great coal fires, or

perhaps they would have

been more careful about

that

beam.

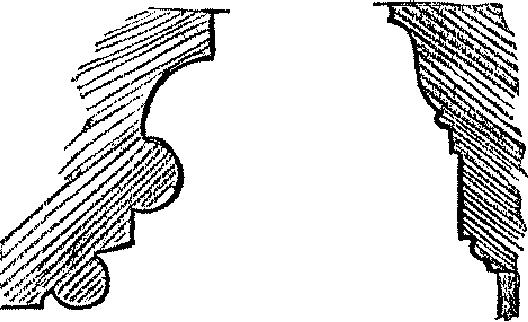

Section

of Mouldings of Cornice on Panelling,

the Church House,

Goudhurst

Fire

is, perhaps, the chief cause

of the vanishing of old houses,

but it is not the

only

cause.

The craze for new fashions

at the beginning of the last

century doomed to

death

many a noble mansion. There

seems to have been a

positive mania for

pulling

down

houses at that period. As I go

over in my mind the existing

great houses in

this

country, I find that by far

the greater number of the

old houses were

wantonly

destroyed

about the years 1800-20, and

new ones in the Italian or

some other

incongruous

style erected in their

place. Sometimes, as at Little Wittenham,

you

find

the lone lorn terraces of

the gardens of the house,

but all else has

disappeared.

As

Mr. Allan Fea says: "When an

old landmark disappears, who

does not feel a

pang

of regret at parting with

something which linked us

with the past? Seldom

an

old

house is threatened with demolition but

there is some protest, more

perhaps

from

the old associations than

from any particular

architectural merit the

building

may

have." We have many pangs of

regret when we see such

wanton destruction.

The

old house at Weston, where

the Throckmortons resided

when the poet Cowper

lived

at the lodge, and when

leaving wrote on a

window-shutter--

Farewell,

dear scenes, for ever closed

to me;

Oh!

for what sorrows must I

now exchange ye!

may

be instanced as an example of a demolished

mansion. Nothing is now left

of it

but

the entrance-gates and a part of the

stables. It was pulled down in 1827. It

is

described

as a fine mansion, possessing

secret chambers which were

occupied by

Roman

Catholic priests when it was

penal to say Mass. One of

these chambers was

found

to contain, when the house was

pulled down, a rough bed,

candlestick,

remains

of food, and a breviary. A Roman

Catholic school and presbytery

now

occupy

its site. It is a melancholy sight to

see the "Wilderness" behind

the house,

still

adorned with busts and urns, and

the graves of favourite dogs,

which still bear

the

epitaphs written by Cowper on Sir

John Throckmorton's pointer and

Lady

Throckmorton's

pet spaniel. "Capability Brown"

laid his rude, rough

hand upon the

grounds,

but you can still

see the "prosed alcove"

mentioned by Cowper, a

wooden

summer-house,

much injured

By

rural carvers, who with

knives deface

The

panels, leaving an obscure rude

name.

Sometimes,

alas! the old house has to

vanish entirely through old

age. It cannot

maintain

its struggle any longer.

The rain pours through

the roof and down

the

insides

of the walls. And the

family is as decayed as their

mansion, and has no

money

wherewith to defray the cost of

reparation.

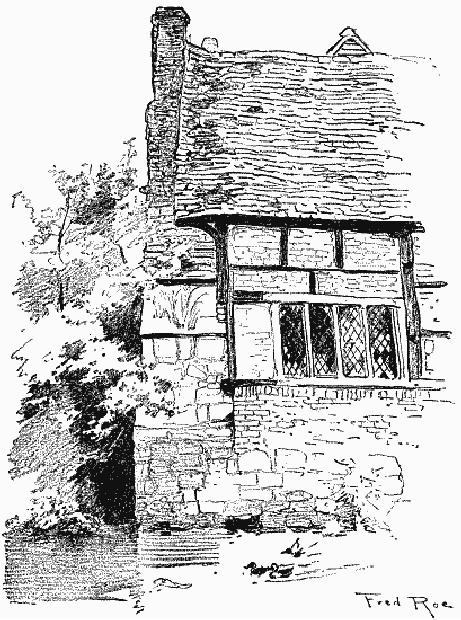

The

Wardrobe House. The Close.

Salisbury. Evening.

Our

artist, Mr. Fred Roe, in his

search for the picturesque,

had one sad and

deplorable

experience, which he shall

describe in his own

words:--

"One

of the most weird and, I

may add, chilling experiences

in

connection

with the decline of county

families which it was my lot

to

experience,

occurred a year or two ago

in a remote corner of

the

eastern

counties. I had received,

through a friend, an invitation to

visit

an

old mansion before the

inmates (descendants of the owners

in

Elizabethan

times) left and the contents

were dispersed. On a

comfortless

January morning, while rain

and sleet descended in

torrents

to the accompaniment of a biting

wind, I detrained at a

small

out-of-the-way

station in ----folk. A weather-beaten old

man in a

patched

great-coat, with the oldest

and shaggiest of ponies and the

smallest

of governess-traps, awaited my arrival.

I, having wedged

myself

with the Jehu into this

miniature vehicle, was

driven through

some

miles of muddy ruts, until

turning through a belt of

wooded land

the

broken outlines of an extensive

dilapidated building broke

into

view.

This was ---- Hall.

"I

never in my life saw anything so

weirdly picturesque and

suggestive

of

the phrase 'In Chancery' as

this semi-ruinous mansion. Of

many

dates

and styles of architecture, from

Henry VIII to George III, the

whole

seemed to breathe an atmosphere of neglect and

decay. The

waves

of affluence and successive rise of

various members of the

family

could be distinctly traced in the

enlargements and excrescences

which

contributed to the casual plan and

irregular contour of

the

building.

At one part an addition seemed to denote

that the owner had

acquired

wealth about the time of

the first James, and

promptly

directed

it to the enlargement of his residence.

In another a huge

hall

with

classic brick frontage, dating

from the commencement of

the

eighteenth

century, spoke of an increase of

affluence--probably due to

agricultural

prosperity--followed by the dignity of a

peerage. The

latest

alterations appear to have

been made during the

Strawberry Hill

epoch,

when most of the mullioned

windows had been transformed

to

suit

the prevailing taste. Some of

the building--a little of

it--seemed

habitable,

but in the greater part the

gables were tottering, the

stucco

frontage

peeling and falling, and

the windows broken and

shuttered. In

front

of this wreck of a building

stretched the overgrown

remains of

what

once had been a terrace, bounded by large

stone globes, now

moss-grown

and half hidden under long

grass. It was the very

picture

of

desolation and proud

poverty.

"We

drove up to what had once

been the entrance to the

servants' hall,

for

the principal doorway had

long been disused, and descending

from

the

trap I was conducted to a

small panelled apartment,

where some

freshly

cut logs did their

best to give out a certain

amount of heat. Of

the

hospitality meted out to me that

day I can only hint

with mournful

appreciation.

I was made welcome with

all the resources which

the

family

had available. But the place

was a veritable vault, and

cold and

damp

as such. I think that this

state of things had been

endured so long

and

with such haughty silence by

the inmates that it had

passed into a

sort

of normal condition with

them, and remained unnoticed

except by

new-comers.

A few old domestics stuck by

the family in its

fallen

fortunes,

and of these one who had entered

into their service

some

quarter

of a century previous waited

upon us at lunch with

dignified

ceremony.

After lunch a tour of the

house commenced. Into this I

shall

not

enter into in detail; many

of the rooms were so bare

that little could

be

said of them, but the

Great Hall, an apartment

modelled somewhat

on

the lines of the more

palatial Rainham, needs the

pen of the author

of

Lammermoor

to

describe. It was a very large and lofty

room in the

pseudo-classic

style, with a fine cornice,

and hung round with

family

portraits

so bleached with damp and neglect that

they presented but

dim

and ghostly presentments of their

originals. I do not think a

fire

could

have been lit in this

ghostly gallery for many

years, and some of

the

portraits literally sagged in

their frames with

accumulations of

rubbish

which had dropped behind the

canvases. Many of the

pictures

were

of no value except for their

associations, but I saw at least one

Lely,

a family group, the

principal figure in which was a

young lady

displaying

too little modesty and too

much bosom. Another may

have

been

a Vandyk, while one or two

were early works

representing

gallants

of Elizabeth's time in ruffs and

feathered caps. The rest

were

for

the most part but

wooden ancestors displaying

curled wigs, legs

which

lacked drawing, and high-heeled

shoes. A few old

cabinets

remained,

and a glorious suite of chairs of

Queen Anne's

time--these,

however,

were perishing, like the

rest--from want of proper

care and

firing.

"The

kitchens, a vast range of stone-flagged

apartments, spoke of

mighty

hospitality in bygone times,

containing fire-places fit to

roast

oxen

at whole, huge spits and

countless hooks, the last

exhibiting but

one

dependent--the skin of the

rabbit shot for lunch.

The atmosphere

was,

if possible, a trifle more penetrating

than that of the Great

Hall,

and

the walls were discoloured

with damp.

"Upstairs,

besides the bedrooms, was a little

chapel with some

remains

of

Gothic carving, and a few

interesting pictures of the

fifteenth

century;

a cunningly contrived priest-hole, and a

long gallery lined

with

dusty books, whither my lord

used to repair on rainy

days. Many

of

the windows were darkened by

creepers, and over one was a flap

of

half-detached

plaster work which hung

like a shroud. But, oh,

the

stained

glass! The eighteenth-century renovators

had at least respected

these,

and quarterings and coats of arms from

the fifteenth century

downwards

were to be seen by scores.

What an opportunity for

the

genealogist

with a history in view, but

that opportunity I fear

has

passed

for ever. The ---- Hall

estate was evidently

mortgaged up to

the

hilt, and nothing intervened to

prevent the dispersal of

these

treasures,

which occurred some few

months after my visit.

Large

though

the building was, I learned

that its size was once far

greater,

some

two-thirds of the old

building having been pulled

down when the

hall

was constituted in its present form.

Hard by on an adjoining

estate

a

millionaire manufacturer (who

owned several motor-cars) had

set up

an

establishment, but I gathered that

his tastes were the reverse

of

antiquarian,

and that no effort would be

made to restore the old hall

to

its

former glories and preserve such

treasures as yet remained

intact--a

golden

opportunity to many people of taste

with leanings towards

a

country

life. But time fled,

and the ragged retainer was

once more at

the

door, so I left ---- Hall in a

blinding storm of rain, and

took my

last

look at its gaunt fa�ade,

carrying with me the seeds

of a cold which

prevented

me from visiting the Eastern

Counties for some time

to

come."

Some

historic houses of rare beauty

have only just escaped

destruction. Such an

one

is the ancestral house of the Comptons,

Compton Wynyates, a vision of

colour

and

architectural beauty--

A

Tudor-chimneyed bulk

Of

mellow brickwork on an isle of

bowers.

Owing

to his extravagance and the

enormous expenses of a contested election

in

1768,

Spencer, the eighth Earl of

Northampton, was reduced to cutting

down the

timber

on the estate, selling his

furniture at Castle Ashby and Compton,

and

spending

the rest of his life in

Switzerland. He actually ordered Compton

Wynyates

to

be pulled down, as he could

not afford to repair it;

happily the faithful steward

of

the

estate, John Berrill, did

not obey the order. He

did his best to keep

out the

weather

and to preserve the house, asserting that

he was sure the family

would

return

there some day. Most of

the windows were bricked up

in order to save the

window-tax,

and the glorious old

building within whose walls

kings and queens

had

been entertained remained

bare and desolate for many

years, excepting a

small

portion

used as a farm-house. All honour to

the old man's memory, the

faithful

servant,

who thus saved his

master's noble house from

destruction, the pride of

the

Midlands.

Its latest historian, Miss

Alice Dryden,34

thus

describes its appearance:--

"On

approaching the building by

the high road, the

entrance front now

bursts

into view across a wide

stretch of lawn, where

formerly it was

shielded

by buildings forming an outer

court. It is indeed a most

glorious

pile of exquisite colouring,

built of small red bricks

widely

separated

by mortar, with occasional chequers of

blue bricks; the

mouldings

and facings of yellow local

stone, the woodwork of the

two

gables

carved and black with age,

the stone slates covered

with lichens

and

mellowed by the hand of

time; the whole building

has an

indescribable

charm. The architecture,

too, is all irregular;

towers here

and

there, gables of different

heights, any straight line

embattled, few

windows

placed exactly over others, and

the whole fitly surmounted

by

the

elaborate brick chimneys of different

designs, some fluted,

others

zigzagged,

others spiral, or combined

spiral and fluted."

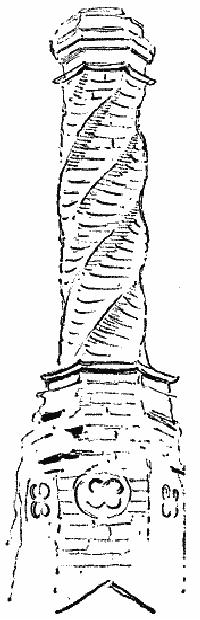

An

illustration is given of one of these

chimneys which form such an

attractive

feature

of the house.

Chimney

at Compton Wynates.

It

is unnecessary to record the

history of Compton Wynyates.

The present owner,

the

Marquis of Northampton, has

written an admirable monograph on

the annals of

the

house of his ancestors. Its builder

was Sir William

Compton,35

who by

his

valour

in arms and his courtly ways gained

the favour of Henry VIII, and

was

promoted

to high honour at the Court.

Dugdale states that in 1520 he

obtained

licence

to impark two thousand acres

at Overcompton and Nethercompton,

alias

Compton

Vyneyats, where he built a

"fair mannour house," and

where he was

visited

by the King, "for over

the gateway are the arms of

France and England,

under

a crown, supported by the

greyhound and griffin, and sided by

the rose and

the

crown, probably in memory of

Henry VIII's visit

here."36

The

Comptons ever

basked

in the smiles of royalty.

Henry Compton, created

baron, was the favourite

of

Queen

Elizabeth, and his son

William succeeded in marrying

the daughter of Sir

John

Spencer, richest of City merchants. All

the world knows of his

ingenious craft

in

carrying off the lady in a

baker's basket, of his wife's

disinheritance by the

irate

father,

and of the subsequent reconciliation

through the intervention of

Queen

Elizabeth

at the baptism of the son of

this marriage. The Comptons

fought bravely

for

the King in the Civil

War. Their house was

captured by the enemy,

and

besieged

by James Compton, Earl of

Northampton, and the story of

the fighting

about

the house abounds in interest, but

cannot be related here. The

building was

much

battered by the siege and by Cromwell's

soldiers, who plundered the

house,

killed

the deer in the park,

defaced the monuments in the

church, and wrought

much

mischief. Since the eighteenth-century

disaster to the family it

has been

restored,

and remains to this day one of

the most charming homes in

England.

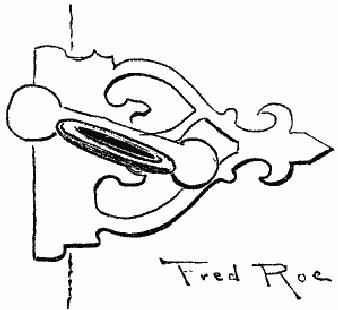

Window-catch,

Brockhall, Northants

"The

greatest advantages men have

by riches are to give, to

build, to plant, and

make

pleasant scenes." So wrote Sir

William Temple, diplomatist,

philosopher, and

true

garden-lover. And many of

the gentlemen of England

seem to have been of

the

same

mind, if we may judge from

the number of delightful old

country-houses set

amid

pleasant scenes that time and

war and fire have spared to

us. Macaulay draws

a

very unflattering picture of

the old country squire, as

of the parson. His

untruths

concerning

the latter I have endeavoured to

expose in another

place.37

The

manor-

houses

themselves declare the historian's

strictures to be unfounded. Is it

possible

that

men so ignorant and crude

could have built for

themselves residences

bearing

evidence

of such good taste, so full of grace and

charm, and surrounded by

such

rare

blendings of art and nature as

are displayed so often in

park and garden? And

it

is

not, as a rule, in the

greatest mansions, the vast

piles erected by the great

nobles

of

the Court, that we find

such artistic qualities, but

most often in the smaller

manor

-houses

of knights and squires. Certainly many

higher-cultured people of

Macaulay's

time and our own

could learn a great deal from

them of the art of

making

beautiful homes.

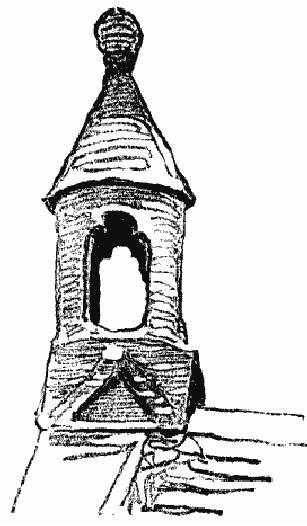

Gothic

Chimney, Norton St. Philip,

Somerset

Holinshed,

the Chronicler, writing

during the third quarter of

the sixteenth

century,

makes

some illuminating observations on

the increasing preference

shown in his

time

for stone and brick buildings in place of

timber and plaster. He

wrote:--

"The

ancient maners and houses of our

gentlemen are yet for

the most

part

of strong timber. How beit

such as be lately buylded

are

commonly

either of bricke or harde stone, their

rowmes large and

stately,

and houses of office farder

distant fro their lodgings.

Those of

the

nobilitie are likewise

wrought with bricke and harde

stone, as

provision

may best be made; but so

magnificent and stately, as

the

basest

house of a barren doth often

match with some honours

of

princes

in olde tyme: so that if

ever curious buylding did

flourishe in

Englande

it is in these our dayes, wherein

our worckemen excel

and

are

in maner comparable in skill

with old Vitruvius and

Serle."

He

also adds the curious

information that "there are

olde men yet dwelling in

the

village

where I remayn, which have

noted three things to be

marveylously altered

in

Englande within their sound

remembrance. One is, the

multitude of chimnies

lately

erected, whereas, in their young dayes

there were not above two or

three, if

so

many, in most uplandish

townes of the realme (the

religious houses and

mannour

places

of their lordes alwayes excepted, and

peradventure some great

personages

[parsonages]),

but each one made his

fire against a reredosse in the

halle, where he

dined

and dressed his meate," This

want of chimneys is noticeable in

many pictures

of,

and previous to, the time of

Henry VIII. A timber farm-house

yet remains (or

did

until recently) near Folkestone,

which shows no vestige of

either chimney or

hearth.

Most

of our great houses and manor-houses

sprang up in the great Elizabethan

building

epoch, when the untold

wealth of the monasteries which

fell into the hands

of

the courtiers and favourites of

the King, the plunder of

gold-laden Spanish

galleons,

and the unprecedented prosperity in trade

gave such an impulse to

the

erection

of fine houses that the

England of that period has

been described as

"one

great

stonemason's yard." The great noblemen

and gentlemen of the Court

were

filled

with the desire for

extravagant display, and

built such clumsy piles

as

Wollaton

and Burghley House, importing

French and German artisans to load

them

with

bastard Italian Renaissance

detail. Some of these vast

structures are not

very

admirable

with their distorted gables,

their chaotic proportions,

and their crazy

imitations

of classic orders. But the typical

Elizabethan mansion, whose

builder's

means

or good taste would not

permit of such a profusion of

these architectural

luxuries,

is unequalled in its combination of

stateliness with homeliness, in

its

expression

of the manner of life of the

class for which it was

built. And in the

humbler

manors and farm-houses the

latter idea is even more

perfectly expressed,

for

houses were affected by the

new fashions in architecture

generally in proportion

to

their size.

The

Moat, Crowhurst Place,

Surrey

Holinshed

tells of the increased use

of stone or brick in his age in

the district

wherein

he lived. In other parts of England,

where the forests supplied

good timber,

the

builders stuck to their

half-timbered houses and brought

the "black and

white"

style

to perfection. Plaster was extensively

used in this and subsequent ages,

and

often

the whole surface of the

house was covered with rough-cast,

such as the

quaint

old house called Broughton

Hall, near Market Drayton.

Avebury Manor,

Wiltshire,

is an attractive example of the plastered

house. The irregular

roof-line,

the

gables, and the white-barred windows, and

the contrast of the white

walls with

the

rich green of the vines and

surrounding trees combine to make a

picture of rare

beauty.

Part of the house is built of stone and

part half-timber, but a coat of

thin

plaster

covers the stonework and

makes it conform with the

rest. To plaster over

stone-work

is a somewhat daring act, and is

not architecturally correct,

but the

appearance

of the house is altogether

pleasing.

The

Elizabethan and Jacobean builder

increased the height of his

house, sometimes

causing

it to have three storeys,

besides rooms in attics beneath

the gabled roof. He

also

loved windows. "Light, more

light," was his continued

cry. Hence there is

often

an excess of windows, and

Lord Bacon complained that

there was no

comfortable

place to be found in these houses, "in

summer by reason of the

heat, or

in

winter by reason of the

cold." It was a sore burden

to many a house-owner

when

Charles

II imposed the iniquitous window-tax, and

so heavily did this fall

upon the

owners

of some Elizabethan houses

that the poorer ones

were driven to the

necessity

of walling up some of the

windows which their

ancestors had provided

with

such prodigality. You will often

see to this day bricked-up

windows in many

an

old farm-house. Not every

one was so cunning as the

parish clerk of

Bradford-

on-Avon,

Orpin, who took out

the window-frames from his

interesting little house

near

the church and inserted

numerous small single-paned

windows which escaped

the

tax.

Surrey

and Kent afford an unlimited

field for the study of

the better sort of

houses,

mansions,

and manor-houses. We have already

alluded to Hever Castle and

its

memories

of Anne Boleyn. Then there

is the historic Penshurst,

the home of the

Sidneys,

haunted by the shades of Sir

Philip, "Sacharissa," the ill-fated

Algernon,

and

his handsome brother. You see

their portraits on the

walls, the fine gallery,

and

the

hall, which reveals the

exact condition of an ancient

noble's hall in former

days.

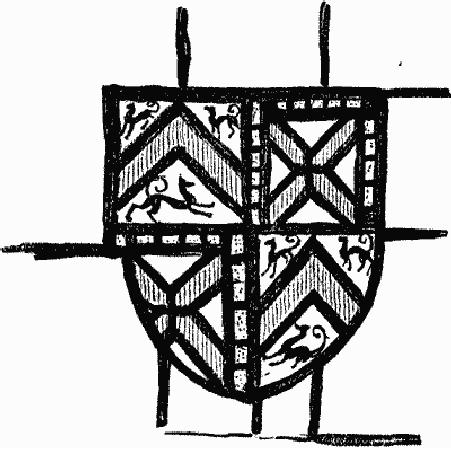

Arms

of the Gaynesfords in window,

Crowhurst Place, Surrey

Not

far away are the

manors of Crittenden, Puttenden, and

Crowhurst. This last

is

one

of the most picturesque in

Surrey, with its moat,

across which there is a

fine

view

of the house, its

half-timber work, the

straight uprights placed close

together

signifying

early work, and the striking

character of the interior. The

Gaynesford

family

became lords of the manor of

Crowhurst in 1337, and

continued to hold it

until

1700, a very long record. In

1903 the Place was purchased by

the Rev. ----

Gaynesford,

of Hitchin, a descendant of the

family of the former owners.

This is a

rare

instance of the repossession of a

medieval residence by an ancient

family after

the

lapse of two hundred years. It was

built in the fifteenth

century, and is a

complete

specimen of its age and style,

having been unspoilt by

later alterations

and

additions. The part nearer

the moat is, however, a

little later than the

gables

further

back. The dining-room is the

contracted remains of the great

hall of

Crowhurst

Place, the upper part of

which was converted into a

series of bedrooms

in

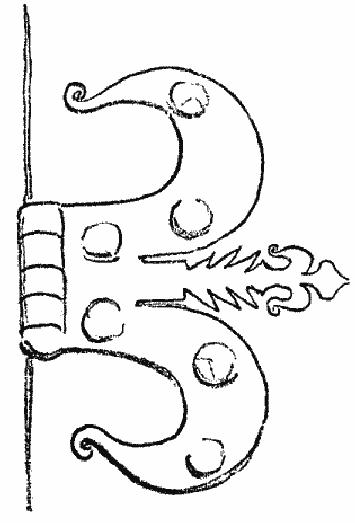

the eighteenth century. We

give an illustration of a very

fine hinge to a

cupboard

door

in one of the bedrooms, a good example of

the blacksmith's skill. It

is

noticeable

that the points of the

linen-fold in the panelling of

the door are

undercut

and

project sharply. We see the

open framed floor with

moulded beams. Later

on

the

fashion changed, and the builders

preferred to have square-shaped

beams. We

notice

the fine old panelling,

the elaborate mouldings, and the

fixed bench running

along

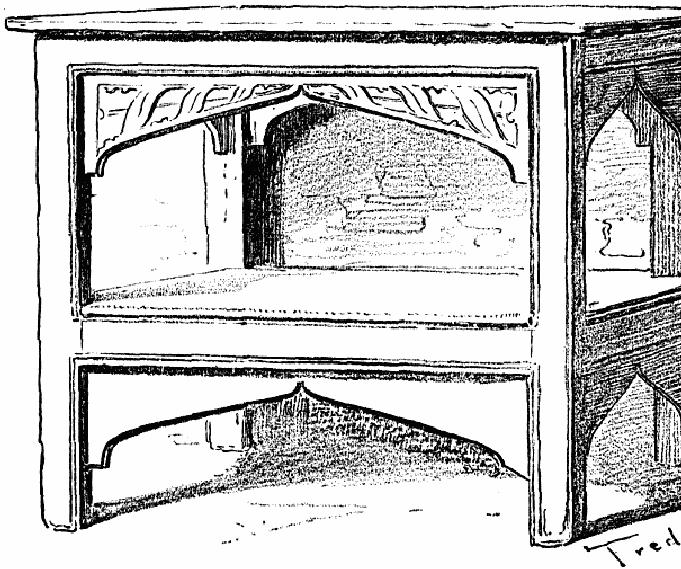

one end of the chamber, of which we

give an illustration. The design

and

workmanship

of this fixture show it to

belong to the period of

Henry VIII. All the

work

is of stout timber, save the

fire-place. The smith's art

is shown in the fine

candelabrum

and in the knocker or ring-plate,

perforated with Gothic design,

still

backed

with its original morocco

leather. It is worthy of a sanctuary,

and doubtless

many

generations of Crowhurst squires have

found a very dear sanctuary

in this

grand

old English home. This

ring-plate is in one of the original

bedrooms.

Immense

labour was often bestowed upon

the mouldings of beams in

these

fifteenth-century

houses. There was a very

fine moulded beam in a

farm-house in

my

own parish, but a recent

restoration has, alas! covered

it. We give some

illustrations

of the cornice mouldings of

the Church House, Goudhurst,

Kent, and

of

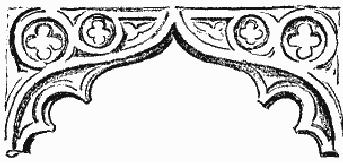

a fine Gothic

door-head.

Cupboard

Hinge, Crowhurst Place,

Surrey

It

is impossible for us to traverse

many shires in our search

for old houses. But a

word

must be said for the

priceless contents of many of our

historic mansions and

manors.

These often vanish and are

lost for ever. I have

alluded to the thirst

of

American

millionaires for these

valuables, which causes so

many of our treasures

to

cross the Atlantic and find

their home in the palaces of

Boston and Washington

and

elsewhere. Perhaps if our

valuables must leave their

old resting-places and go

out

of the country, we should

prefer them to go to America

than to any other

land.

Our

American cousins are our

kindred; they know how to

appreciate the

treasures

of

the land that, in spite of

many changes, is to them their

mother-country. No

nation

in the world prizes a high

lineage and a family tree more

than the

Americans,

and it is my privilege to receive many

inquiries from across the

Atlantic

for

missing links in the family

pedigree, and the joy that a

successful search

yields

compensates

for all one's trouble. So if

our treasures must go we

should rather send

them

to America than to Germany. It

is, however, distressing to

see pictures taken

from

the place where they have

hung for centuries and sent to

Christie's, to see

the

dispersal

of old libraries at Sotherby's,

and the contents of a house,

amassed by

generations

of cultured and wealthy folk,

scattered to the four winds

and bought up

by

the nouveaux

riches.

Fixed

Bench in the Hall, Crowhurst

Place, Surrey

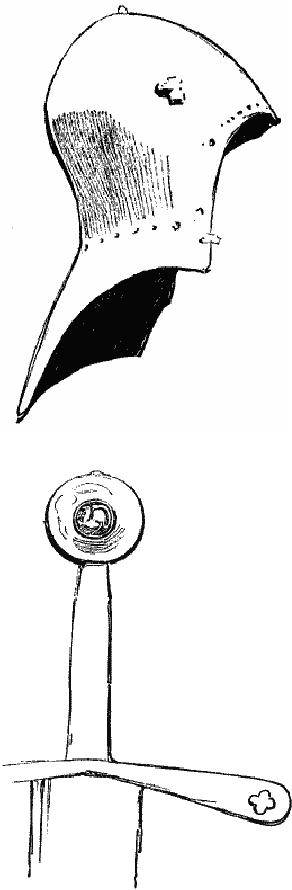

There

still remain in many old

houses collections of armour

that bears the dints

of

many

fights. Swords, helmets,

shields, lances, and other weapons of

warfare often

are

seen hanging on the walls of

an ancestral hall. The buff

coats of Cromwell's

soldiers,

tilting-helmets, guns and

pistols of many periods are

all there, together

with

man-traps--the cruel invention of a

barbarous age.

Gothic

Door-head, Goudhurst,

Kent

The

historic hall of Littlecote

bears on its walls many

suits worn during the

Civil

War

by the Parliamentary troopers, and in

countless other halls you

can see

specimens

of armour. In churches also much

armour has been stored. It was

the

custom

to suspend over the tomb

the principal arms of the

departed warrior,

which

had

previously been carried in

the funeral procession. Shakespeare

alludes to this

custom

when, in Hamlet,

he makes Laertes say:--

His

means of death, his obscure

burial--

No

trophy, sword, nor hatchment

o'er his bones,

No

noble rite, nor formal

ostentation.

You

can see the armour of the

Black Prince over his

tomb at Canterbury, and at

Westminster

the shield of Henry V that

probably did its duty at

Agincourt. Several

of

our churches still retain

the arms of the heroes who

lie buried beneath them,

but

occasionally

it is not the actual armour

but sham, counterfeit

helmets and

breastplates

made for the funeral

procession and hung over the

monument. Much of

this

armour has been removed

from churches and stored in

museums. Norwich

Museum

has some good specimens, of which we

give some illustrations.

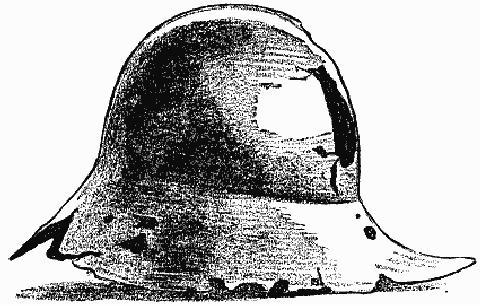

There is a

knight's

basinet which belongs to the

time of Henry V (circa

1415).

We can

compare

this with the salads,

which came into use

shortly after this period,

an

example

of which may be seen at the

Porte d'Hal, Brussels. We also show

a

thirteenth-century

sword, which was dredged up at

Thorpe, and believed to

have

been

lost in 1277, when King

Edward I made a military

progress through

Suffolk

and

Norfolk, and kept his Easter

at Norwich. The blade is scimitar-shaped,

is one-

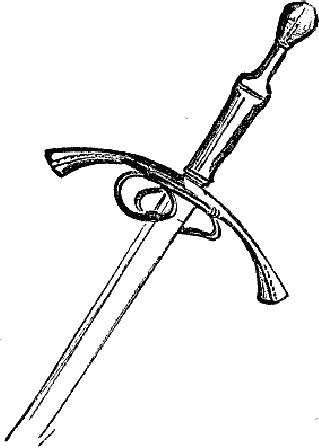

edged,

and has a groove at the

back. We may compare this

with the sword of

the

time

of Edward IV now in the

possession of Mr. Seymour Lucas.

The development

of

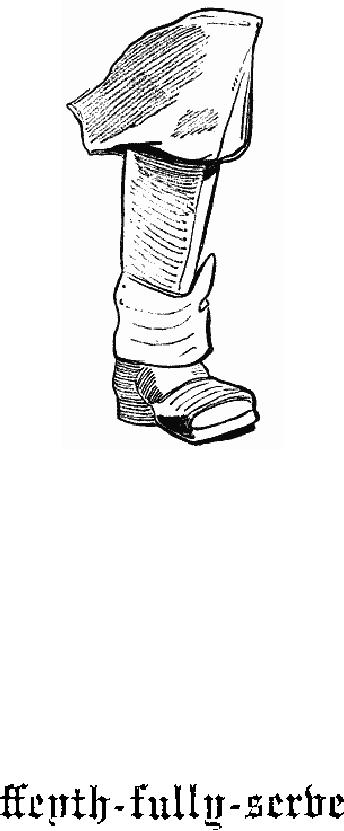

riding-boots is an interesting study. We

show a drawing of one in the

possession

of

Mr. Ernest Crofts, R.A.,

which was in use in the time

of William III.

Knightly

Basinet (temp.

Henry

V) in Norwich Castle

Hilt

of Thirteenth-century Sword in Norwich

Museum

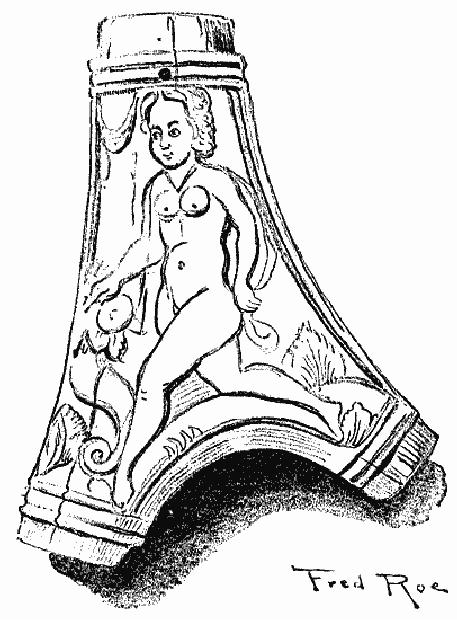

An

illustration is given of a chapel-de-fer

which reposes in the noble

hall of

Ockwells,

Berkshire, much dented by use. It

has evidently seen service.

In the same

hall

is collected by the friends of

the author, Sir Edward and

Lady Barry, a vast

store

of armour and most interesting

examples of ancient furniture

worthy of the

beautiful

building in which they are

placed. Ockwells Manor House

is goodly to

look

upon, a perfect example of

fifteenth-century residence with

its noble hall and

minstrels'

gallery, its solar,

kitchens, corridors, and gardens.

Moreover, it is now

owned

by those who love and respect

antiquity and its architectural beauties,

and is

in

every respect an old English

mansion well preserved and tenderly

cared for. Yet

at

one time it was almost doomed to

destruction. Not many years

ago it was the

property

of a man who knew nothing of

its importance. He threatened to pull

it

down

or to turn the old house

into a tannery. Our Berks

Arch�ological Society

endeavoured

to raise money for its

purchase in order to preserve it. This

action

helped

the owner to realise that

the house was of some

commercial value. Its

destruction

was stayed, and then, happily, it was purchased by

the present owners,

who

have done so much to restore its

original beauties.

"Hand-and-a-half"

Sword. Mr. Seymour Lucas,

R.A.

Seventeenth-century

Boot, in the possession of

Ernest Crofts, Esq.,

R.A.

Ockwells

was built by Sir John

Norreys about the year

1466. The chapel was

not

completed

at his death in 1467, and he left

money in his will "to the

full bilding and

making

uppe of the Chapell with the

Chambres ajoyng with'n my manoir of

Okholt

in

the p'rish of Bray aforsaid

not yet finisshed XL li."

This chapel was burnt

down

in

1778. One of the most

important features of the hall is

the heraldic glass,

commemorating

eighteen worthies, which is of

the same date as the house.

The

credit

of identifying these worthies is due to

Mr. Everard Green, Rouge

Dragon,

who

in 1899 communicated the result of

his researches to Viscount

Dillon,

President

of the Society of Antiquaries.

There are eighteen shields

of arms. Two are

royal

and ensigned with royal crowns. Two

are ensigned with mitres and

fourteen

with

mantled helms, and of these

fourteen, thirteen support a crest.

Each

achievement

is placed in a separate light on an

ornamental background

composed

of

quarries and alternate diagonal stripes

of white glass bordered with

gold, on

which

the motto

is

inscribed in black-letter. This

motto is assigned by some to

the family of Norreys

and

by others as that of the

Royal Wardrobe. The quarries

in each light have

the

same

badge, namely, three golden

distaffs, one in pale and two in saltire,

banded

with

a golden and tasselled ribbon, which

badge some again assign to

the family of

Norreys

and others to the Royal

Wardrobe. If, however, the

Norreys arms are

correctly

set forth in a compartment of a door-head

remaining in the north wall,

and

also

in one of the windows--namely, argent a

chevron between three

ravens' heads

erased

sable, with a beaver for a

dexter supporter--the second

conjecture is

doubtless

correct.

Chapel

de Fer at Ockwells, Berks

These

shields represent the arms of Sir

John Norreys, the builder of

Ockwells

Manor

House, and of his sovereign,

patrons, and kinsfolk. It is a liber

amicorum in

glass,

a not unpleasant way for

light to come to us, as Mr. Everard

Green pleasantly

remarks.

By means of heraldry Sir

John Norreys recorded his

friendships, thereby

adding

to the pleasures of memory as

well as to the splendour of

his great hall. His

eye

saw the shield, his

memory supplied the story,

and to him the lines of

George

Eliot,

O

memories,

O

Past that IS,

were

made possible by heraldry.

The

names of his friends and

patrons so recorded in glass by their

arms are: Sir

Henry

Beauchamp, sixth Earl of

Warwick; Sir Edmund

Beaufort, K.G.;

Margaret

of

Anjou, Queen of Henry VI,

"the dauntless queen of tears, who

headed councils,

led

armies, and ruled both king

and people"; Sir John de la

Pole, K.G.; Henry VI;

Sir

James Butler; the Abbey of

Abingdon; Richard Beauchamp,

Bishop of

Salisbury

from 1450 to 1481; Sir John

Norreys himself; Sir John

Wenlock, of

Wenlock,

Shropshire; Sir William

Lacon, of Stow, Kent, buried

at Bray; the arms

and

crest of a member of the Mortimer

family; Sir Richard Nanfan,

of Birtsmorton

Court,

Worcestershire; Sir John

Norreys with his arms

quartered with those of

Alice

Merbury, of Yattendon, his

first wife; Sir John

Langford, who married

Sir

John

Norreys's granddaughter; a member of

the De la Beche family (?);

John

Purye,

of Thatcham, Bray, and Cookham;

Richard Bulstrode, of

Upton,

Buckinghamshire,

Keeper of the Great Wardrobe to

Queen Margaret of Anjou,

and

afterwards

Comptroller of the Household to

Edward IV. These are the

worthies

whose

arms are recorded in the windows of

Ockwells. Nash gave a drawing of

the

house

in his Mansions

of England in the Olden

Time, showing

the interior of the

hall,

the porch and corridor, and

the east front; and from

the hospitable door

is

issuing

a crowd of gaily dressed people in

Elizabethan costume, such as

was

doubtless

often witnessed in days of yore. It is a

happy and fortunate event

that this

noble

house should in its old age

have found such a loving

master and mistress, in

whose

family we hope it may remain

for many long years.

Another

grand old house has just

been saved by the National

Trust and the

bounty

of

an anonymous benefactor. This is

Barrington Court, and is one of the

finest

houses

in Somerset. It is situated a few miles

east of Ilminster, in the

hundred of

South

Petherton. Its exact age is

uncertain, but it seems

probable that it was built

by

Henry,

Lord Daubeney, created Earl

of Bridgewater in 1539, whose

ancestors had

owned

the place since early Plantagenet times.

At any rate, it appears to

date from

about

the middle of the sixteenth

century, and it is a very perfect

example of the

domestic

architecture of that period.

From the Daubeneys it passed

successively to

the

Duke of Suffolk, the Crown,

the Cliftons, the Phelips's,

the Strodes; and one of

this

last family entertained the

Duke of Monmouth there

during his tour in the

west

in

1680. The house, which is

E-shaped,

with central porch and wings

at each end, is

built

of the beautiful Ham Hill stone

which abounds in the district;

the colour of

this

stone greatly enhances the

appearance of the house and adds to

its venerable

aspect.

It has little ornamental

detail, but what there is is

very good, while

the

loftiness

and general proportions of the

building--its extent and solidity

of

masonry,

and the taste and care with

which every part has

been designed and

carried

out, give it an air of

dignity and importance.

"The

angle buttresses to the

wings and the porch

rising to twisted

terminals

are a feature surviving from

medi�val times, which

disappeared

entirely in the buildings of

Stuart times. These

twisted

terminals

with cupola-like tops are also

upon the gables, and with

the

chimneys,

also twisted, give a most

pleasing and attractive character

to

the

structure. We may go far, indeed,

before we find another house

of

stone

so lightly and gracefully adorned, and

the detail of the

mullioned

windows

with their arched heads, in

every light, and their

water-tables

above,

is admirable. The porch also

has a fine Tudor arch,

which might

form

the entrance to some college

quadrangle, and there are

rooms

above

and gables on either hand.

The whole structure breathes

the

spirit

of the Tudor age, before

the classic spirit had exercised

any

marked

influence upon our national

architecture, while the

details of

the

carving are almost as rich

as is the moulded and sculptured

work in

the

brick houses of East Anglia.

The features in other parts of

the

exterior

are all equally good,

and we may certainly say of

Barrington

Court

that it occupies a most notable place in

the domestic

architecture

of

England. It is also worthy of remark

that such houses as this

are far

rarer

than those of Jacobean

times."38

But

Barrington Court has fallen

on evil days; one half of

the house only is now

habitable,

the rest having been

completely gutted about

eighty years ago. The great

hall

is used as a cider store, the

wainscoting has been

ruthlessly removed, and

there

have

even been recent suggestions of

moving the whole structure

across England

and

re-erecting it in a strange county. It

has several times changed hands in

recent

years,

and under these circumstances it is

not surprising that but

little has been done

to

ensure the preservation of what is indeed

an architectural gem. But

the walls are

in

excellent condition and the

roofs fairly sound. The

National Trust, like an

angel

of

mercy, has spread its

protecting wings over the

building; friends have

been

found

to succour the Court in its

old age; and there is every

reason to hope that

its

evil

days are past, and that it may

remain standing for many

generations.

Tudor

Dresser Table, in the

possession of Sir Alfred

Dryden, Canon's Ashby,

Northants

The

wealth of treasure to be found in many

country houses is indeed enormous.

In

Holinshed's

Chronicle

of Englande, Scotlande and Irelande,

published in 1577,

there

is a chapter on the "maner of

buylding and furniture of our

Houses," wherein

is

recorded the costliness of the

stores of plate and tapestry

that were found in

the

dwellings

of nobility and gentry and also in

farm-houses, and even in the homes

of

"inferior

artificers." Verily the

spoils of the monasteries and

churches must have

been

fairly evenly divided. These

are his words:--

"The

furniture of our houses also exceedeth,

and is growne in maner

even

to passing delicacie; and herein I do

not speake of the

nobilitie

and

gentrie onely, but even of

the lowest sorte that have

anything to

take

to. Certes in noble men's

houses it is not rare to see abundance

of

array,

riche hangings of tapestry,

silver vessell, and so much

other

plate

as may furnish sundrie cupbordes to

the summe ofte times of

a

thousand

or two thousand pounde at

the leaste; wherby the value

of

this

and the reast of their

stuffe doth grow to be

inestimable. Likewise

in

the houses of knightes,

gentlemen, marchauntmen, and

other

wealthie

citizens, it is not geson to

beholde generallye their

great

provision

of tapestrie Turkye worke, pewter,

brasse,

fine linen, and

thereto

costly cupbords of plate

woorth five or six hundred

pounde, to

be

demed by estimation. But as

herein all these sortes

doe farre

exceede

their elders and predecessours, so in

tyme past the

costly

furniture

stayed

there, whereas

now it is descended yet

lower, even

unto

the inferior artificiers and

most fermers39

who

have learned to

garnish

also their cupbordes with plate,

their beddes with tapestrie

and

silk

hanginges, and their table

with fine naperie whereby

the wealth of

our

countrie doth infinitely

appeare...."

Much

of this wealth has, of

course, been scattered. Time,

poverty, war, the rise

and

fall

of families, have caused the

dispersion of these treasures. Sometimes

you find

valuable

old prints or china in obscure and

unlikely places. A friend of the

writer,

overtaken

by a storm, sought shelter in a

lone Welsh cottage. She

admired and

bought

a rather curious jug. It

turned out to be a somewhat rare and

valuable ware,

and

a sketch of it has since been

reproduced in the Connoisseur.

I have myself

discovered

three Bartolozzi engravings in

cottages in this parish. We

give an

illustration

of a seventeenth-century powder-horn

which was found at

Glastonbury

by

Charles Griffin in 1833 in the

wall of an old house which

formerly stood where

the

Wilts and Dorset Bank is now

erected. Mr. Griffin's account of its

discovery is

as

follows:--

"When

I was a boy about fifteen years of

age I took a ladder up

into

the

attic to see if there was

anything hid in some holes

that were just

under

the roof.... Pushing my hand

in the wall ... I pulled

out this

carved

horn, which then had a

metal rim and cover--of

silver, I think.

A

man gave me a shilling for

it, and he sold it to Mr.

Porch."

It

is stated that a coronet was

engraved or stamped on the

silver rim which has

now

disappeared.

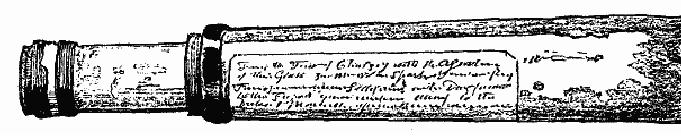

Seventeenth-century

Powder-horn, found in the

wall of an old house at

Glastonbury.

Now in Glastonbury

Museum

Monmouth's

harassed army occupied

Glastonbury on the night of June

22, 1685,

and

it is extremely probable that

the powder-horn was

deposited in its

hiding-place

by

some wavering follower who

had decided to abandon the Duke's

cause. There is

another

relic of Monmouth's rebellion,

now in the Taunton Museum, a

spy-glass,

with

the aid of which Mr. Sparke, from

the tower of Chedzoy,

discovered the

King's

troops marching down

Sedgemoor on the day

previous to the fight, and

gave

information

thereof to the Duke, who was

quartered at Bridgwater. It was

preserved

by

the family for more

than a century, and given by

Miss Mary Sparke, the

great-

granddaughter

of the above William Sparke, in 1822 to a Mr.

Stradling, who placed

it

in the museum. The

spy-glass, which is of very

primitive construction, is in

four

sections

or tubes of bone covered with parchment.

Relics of war and fighting

are

often

stored in country houses. Thus at

Swallowfield Park, the

residence of Lady

Russell,

was found, when an old tree

was grubbed up, some gold

and silver coins of

the

reign of Charles I. It is probable

that a Cavalier, when hard

pressed, threw his

purse

into a hollow tree,

intending, if he escaped, to return and

rescue it. This,

for

some

reason, he was unable to do, and his

money remained in the tree

until old age

necessitated

its removal. The late

Sir George Russell, Bart.,

caused a box to be

made

of the wood of the tree, and

in it he placed the coins, so that

they should not

be

separated after their

connexion of two centuries

and a half.

Seventeenth-century

Spy-glass in Taunton Museum

We

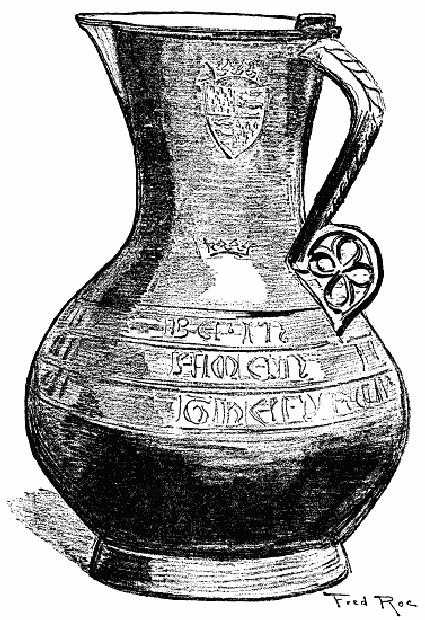

give an illustration of a remarkable

flagon of bell-metal for

holding spiced

wine,

found in an old manor-house in

Norfolk. It is of English make, and

was

manufactured

about the year 1350. It is

embossed with the old

Royal Arms of

England

crowned and repeated several

times, and has an inscription in

Gothic

letters:--

God

is grace Be in this

place.

Amen.

Stand

uttir40

from

the fier

And

let onjust41

come

nere.

Fourteenth-century

Flagon. From an old Manor

House in Norfolk

This

interesting flagon was bought

from the Robinson Collection

in 1879 by the

nation,

and is now in the Victoria and

Albert Museum.

Many

old houses, happily, contain

their stores of ancient

furniture. Elizabethan

bedsteads

wherein, of course, the Virgin

Queen reposed (she made so

many royal

progresses

that it is no wonder she

slept in so many places), expanding

tables,

Jacobean

chairs and sideboards, and later on

the beautiful productions

of

Chippendale,

Sheraton, and Hipplethwaite. Some of

the family chests are

elaborate

works

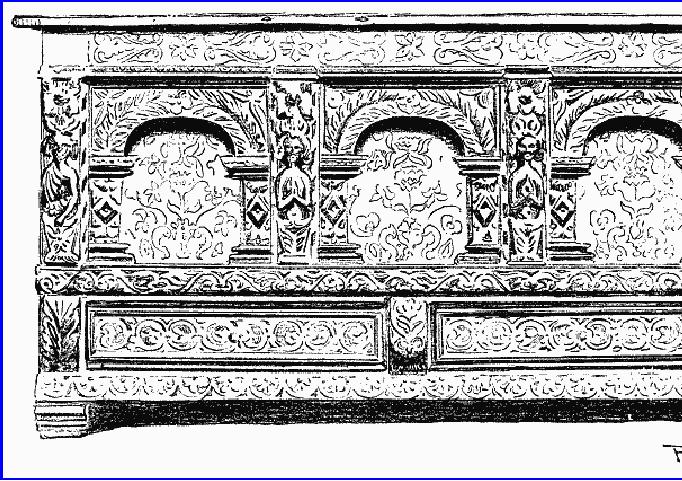

of art. We give as an illustration a

fine example of an Elizabethan

chest. It is

made

of oak, inlaid with holly,

dating from the last

quarter of the sixteenth

century.

Its

length is 5 ft. 2 in., its

height 2 ft. 11 in. It is in

the possession of Sir

Coleridge

Grove,

K.C.B., of the manor-house,

Warborough, in Oxfordshire. The

staircases are

often

elaborately carved, which

form a striking feature of

many old houses. The

old

Aldermaston

Court was burnt down,

but fortunately the huge

figures on the

staircase

were saved and appear again in

the new Court, the

residence of a

distinguished

antiquary, Mr. Charles Keyser,

F.S.A. Hartwell House,

in

Buckinghamshire,

once the residence of the

exiled French Court of Louis

XVIII

during

the Revolution and the

period of the ascendancy of Napoleon I,

has some

curiously

carved oaken figures adorning

the staircase, representing

Hercules, the

Furies,

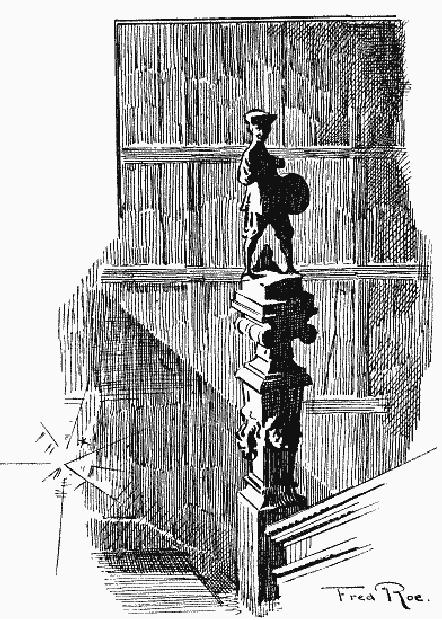

and various knights in armour. We

give an illustration of the

staircase newel

in

Cromwell House, Highgate,

with its quaint little

figure of a man standing on

a

lofty

pedestal.

Elizabethan

Chest, in the possession of

Sir Coleridge Grove, K.C.B.

Height, 2 ft. 11

in.;

length, 5 ft. 2 in.

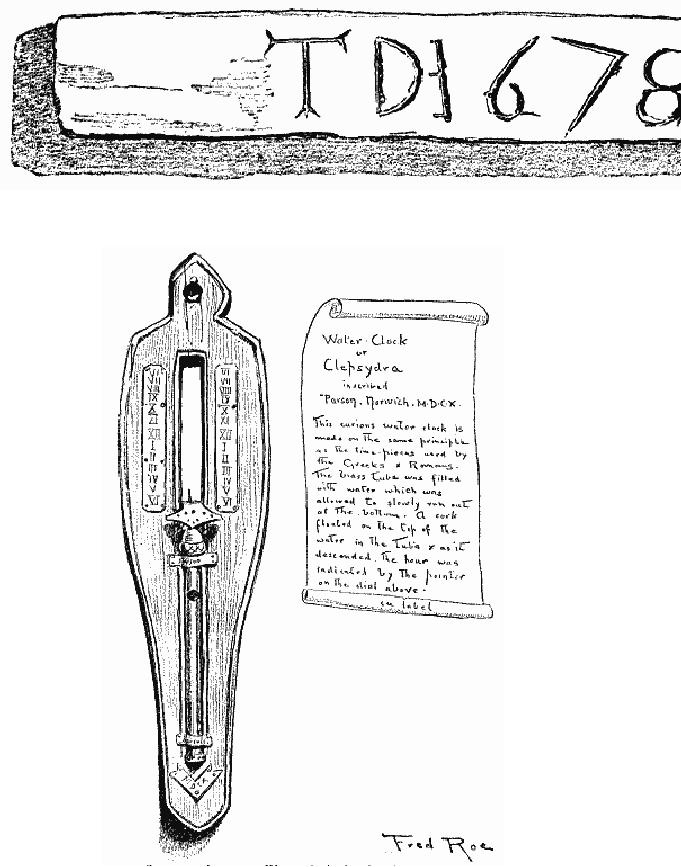

Sometimes

one comes across strange curiosities in

old houses, the odds and

ends

which

Time has accumulated. On p. 201 is a

representation of a water-clock or

clepsydra

which was made at Norwich by an

ingenious person named Parson in

1610.

It is constructed on the same

principle as the timepieces used by

the Greeks

and

Romans. The brass tube

was filled with water,

which was allowed to run

out

slowly

at the bottom. A cork

floated at the top of the

water in the tube, and as

it

descended

the hour was indicated by

the pointer on the dial

above. This ingenious

clock

has now found its

way into the museum in

Norwich Castle. The

interesting

contents

of old houses would require

a volume for their complete

enumeration.

In

looking at these ancient

buildings, which time has

spared us, we seem to catch

a

glimpse

of the Lamp of Memory which

shines forth in the illuminated

pages of

Ruskin.

The men, our forefathers,

who built these houses,

built them to last, and

not

for

their own generation. It

would have grieved them to

think that their

earthly

abode,

which had seen and seemed

almost to sympathize in all

their honour, their

gladness

or their suffering--that this,

with all the record it

bare of them, and of

all

material

things that they had loved

and ruled over, and set the

stamp of themselves

upon--was

to be swept away as soon as there was

room made for them in

the

grave.

They valued and prized

the house that they had reared, or

added to, or

improved.

Hence they loved to carve

their names or their

initials on the lintels

of

their

doors or on the walls of their

houses with the date. On

the stone houses of

the

Cotswolds,

in Derbyshire, Lancashire, Cumberland,

wherever good building stone

abounds,

you can see these

inscriptions, initials usually those of

husband and wife,

which

preserved the memorial of their

names as long as the house

remained in the

family.

Alas! too often the

memorial conveys no meaning, and no one

knows the

names

they represent. But it was a worthy

feeling that prompted this

building for

futurity.

There is a mystery about the

inscription recorded in the illustration

"T.D.

1678."

It was discovered, together

with a sword (temp.

Charles

II), between the

ceiling

and the floor when an old

farm-house called Gundry's, at

Stoke-under-Ham,

was

pulled down. The year was

one of great political disturbance, being

that in

which

the so-called "Popish Plot"

was exploited by Titus Oates. Possibly

"T.D."

was

fearful of being implicated, concealed

this inscription, and effected

his escape.

Staircase

Newel Cromwell House,

Highgate

Our

forefathers must have been

animated by the spirit which

caused Mr. Ruskin to

write:

"When we build, let us think

that we build for ever.

Let it not be for

present

delight,

nor for present use alone;

let it be such work as our

descendants will thank

us

for, and let us think, as we

lay stone on stone, that a time is to

come when those

stones

will be held sacred because

our hands have touched them,

and that men will

say

as they look upon the

labour and wrought substance of them,

'See! this our

fathers

did for us.'"

Piece

of Wood Carved with

Inscription Found with a

sword (temp.

Charles

II) in an

old

house at Stoke-under-Ham, Somerset

Seventeenth-century

Water-clock, in Norwich

Museum

Contrast

these old houses with

the modern suburban

abominations, "those

thin

tottering

foundationless shells of splintered

wood and imitated stone,"

"those

gloomy

rows of formalised minuteness,

alike without difference and

without

fellowship,

as solitary as similar," as Ruskin

calls them. These modern

erections

have

no more relation to their

surroundings than would a

Pullman-car or a newly

painted

piece of machinery. Age

cannot improve the

appearance of such things.

But

age

only mellows and improves

our ancient houses. Solidly

built of good materials,

the

golden stain of time only

adds to their beauties. The

vines have clothed

their

walls

and the green lawns about

them have grown smoother

and thicker, and

the

passing

of the centuries has served

but to tone them down and

bring them into

closer

harmony with nature. With

their garden walls and

hedges they almost

seem

to

have grown in their places

as did the great trees that

stand near by. They

have

nothing

of the uneasy look of the

parvenu about them. They

have an air of

dignified

repose;

the spirit of ancient peace

seems to rest upon them and

their beautiful

surroundings.

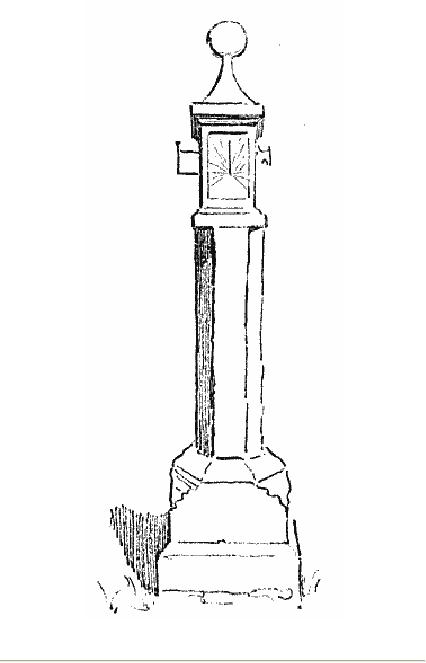

Sun-dial.

The Manor House, Sutton

Courtenay

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION