|

VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES |

| << OLD CASTLES |

| OLD MANSIONS >> |

Knightly

Bascinet (temp.

Henry

V) in Norwich Castle

CHAPTER

VI

VANISHING OR VANISHED

CHURCHES

No

buildings have suffered more

than our parish churches in

the course of ages.

Many

have vanished entirely. A

few stones or ruins mark

the site of others, and

iconoclasm

has left such enduring

marks on the fabric of many

that remain that it

is

difficult

to read their story and

history. A volume, several

volumes, would be

needed

to record all the vandalism

that has been done to our

ecclesiastical

structures

in the ages that have

passed. We can only be thankful

that some churches

have

survived to proclaim the

glories of English architecture and

the skill of our

masons

and artificers who wrought

so well and worthily in

olden days.

In

the chapter that relates to

the erosion of our coasts we

have mentioned many

of

the

towns and villages which

have been devoured by the

sea with their

churches.

These

now lie beneath the waves,

and the bells in their

towers are still said to

ring

when

storms rage. We need not

record again the submerged Ravenspur,

Dunwich,

Kilnsea,

and other unfortunate towns

with their churches where

now only mermaids

can

form the

congregation.

And

as the fisherman

strays

When

the clear cold eve's

declining,

He

sees the round tower of

other days

In

the wave beneath him

shining.

In

the depths of the country,

far from the sea, we can

find many deserted

shrines,

many

churches that once echoed

with the songs of praise of

faithful worshippers,

wherein

were celebrated the divine

mysteries, and organs pealed

forth celestial

music,

but now forsaken,

desecrated, ruined,

forgotten.

The

altar has vanished, the

rood screen flown,

Foundation

and buttress are

ivy-grown;

The

arches are shattered, the

roof has gone,

The

mullions are mouldering one by

one;

Foxglove

and cow-grass and waving

weed

Grow

over the scrolls where

you once could read

Benedicite.

Many

of them have been used as

quarries, and only a few

stones remain to mark

the

spot

where once stood a holy house of God.

Before the Reformation the

land must

have

teemed with churches. I know

not the exact number of

monastic houses once

existing

in England. There must have

been at least a thousand, and each had

its

church.

Each parish had a church.

Besides these were the

cathedrals, chantry

chapels,

chapels attached to the mansions, castles,

and manor-houses of the

lords

and

squires, to almshouses and hospitals, pilgrim

churches by the roadside,

where

bands

of pilgrims would halt and

pay their devotions ere

they passed along to

the

shrine

of St. Thomas at Canterbury or to

Our Lady at Walsingham. When

chantries

and

guilds as well as monasteries were

suppressed, their chapels were no

longer

used

for divine service; some of

the monastic churches became

cathedrals or parish

churches,

but most of them were

pillaged, desecrated, and destroyed.

When

pilgrimages

were declared to be "fond things

vainly invented," and the

pilgrim

bands

ceased to travel along the

pilgrim way, the wayside

chapel fell into decay,

or

was

turned into a barn or

stable.

It

is all very sad and

deplorable. But the roll of

abandoned shrines is not

complete.

At

the present day many old

churches are vanishing. Some

have been abandoned

or

pulled

down because they were

deemed too near to the squire's house,

and a new

church

erected at a more respectful distance.

"Restoration" has doomed many

to

destruction.

Not long ago the

new scheme for supplying

Liverpool with water

necessitated

the converting of a Welsh

valley into a huge reservoir

and the

consequent

destruction of churches and villages. A

new scheme for

supplying

London

with water has been

mooted, and would entail

the damming up of a river

at

the

end of a valley and the

overwhelming of several prosperous old

villages and

churches

which have stood there for

centuries. The destruction of

churches in

London

on account of the value of

their site and the migration of

the population,

westward

and eastward, has been frequently

deplored. With the exception

of All

Hallows,

Barking; St. Andrew's

Undershaft; St. Catherine Cree;

St. Dunstan's,

Stepney;

St. Giles', Cripplegate; All

Hallows, Staining; St.

James's, Aldgate; St.

Sepulchre's;

St. Mary Woolnoth; all

the old City churches

were destroyed by the

Great

Fire, and some of the above

were damaged and repaired. "Destroyed by

the

Great

Fire, rebuilt by Wren," is

the story of most of the

City churches of

London.

To

him fell the task of

rebuilding the fallen

edifices. Well did he

accomplish his

task.

He had no one to guide him; no school of

artists or craftsmen to help

him in

the

detail of his buildings; no great

principles of architecture to direct

him. But he

triumphed

over all obstacles and

devised a style of his own

that was well

suitable

for

the requirements of the time

and climate and for the

form of worship of

the

English

National Church. And how

have we treated the buildings

which his genius

devised

for us? Eighteen of his

beautiful buildings have

already been

destroyed,

and

fourteen of these since the

passing of the Union of City

Benefices Act in 1860

have

succumbed. With the utmost

difficulty vehement attacks on others

have been

warded

off, and no one can tell how

long they will remain. Here

is a very sad and

deplorable

instance of the vanishing of

English architectural treasures. While

we

deplore

the destructive tendencies of our

ancestors we have need to be

ashamed of

our

own.

We

will glance at some of these

deserted shrines on the

sites where formerly

they

stood.

The Rev. Gilbert Twenlow

Royds, Rector of Haughton and

Rural Dean of

Stafford,

records three of these in his

neighbourhood, and shall describe

them in his

own

words:--

"On

the main road to Stafford, in a

field at the top of

Billington Hill, a

little

to the left of the road,

there once stood a chapel. The

field is still

known

as Chapel Hill; but not a

vestige of the building

survives; no

doubt

the foundations were grubbed

up for ploughing purposes. In a

State

paper, describing 'The State of

the Church in Staffs, in

1586,' we

find

the following entry:

'Billington Chappell; reader, a

husbandman;

pension

16 groats; no preacher.' This is

under the heading of

Bradeley,

in

which parish it stood. I have

made a wide search for

information as

to

the dates of the building

and destruction of this chapel.

Only one

solitary

note has come to my

knowledge. In Mazzinghi's History

of

Castle

Church he writes:

'Mention is made of Thomas

Salt the son of

Richard

Salt and C(lem)ance his wife

as Christened at Billington

Chapel

in 1600.' Local tradition

says that within the

memory of the last

generation

stones were carted from this

site to build the

churchyard

wall

of Bradley Church. I have

noticed several re-used stones;

but

perhaps

if that wall were to be more

closely examined or pulled

down,

some

further history might disclose

itself. Knowing that some of

the

stones

were said to be in a garden on the

opposite side of the road,

I

asked

permission to investigate. This

was most kindly granted, and

I

was

told that there was a stone

'with some writing on it' in

a wall. No

doubt

we had the fragment of a gravestone!

and such it proved to

be.

With

some difficulty we got the

stone out of the wall; and,

being an

expert

in pal�ography, I was able to decipher

the inscription. It ran

as

follows:

'FURy. Died Feb. 28,

1864.' A skilled antiquary

would

probably

pronounce it to be the headstone of a

favourite dog's

grave;

and

I am inclined to think that we

have here a not unformidable

rival of

the

celebrated

�

BIL

ST

UM

PS

HI

S.M.

ARK

of

the Pickwick

Papers.

"Yet

another vanished chapel, of

which I have even less to

tell you. On

the

right-hand side of the

railway line running towards

Stafford, a little

beyond

Stallbrook Crossing, there is a

field known as Chapel

Field.

But

there is nothing but the

name left. From ancient

documents I have

learnt

that a chapel once stood there,

known as Derrington Chapel

(I

think

in the thirteenth century), in

Seighford parish, but served

from

Ranton

Priory. In 1847 my father built a

beautiful little church

at

Derrington,

in the Geometrical Decorated style,

but not on the

Chapel

Field.

I cannot tell you what an

immense source of satisfaction it

would

be to me if I could gather some

further reliable information as

to

the

history, style, and

annihilation of these two

vanished chapels. It is

unspeakably

sad to be forced to realize

that in so many of our

country

parishes

no records exist of things and events of

surpassing interest in

their

histories.

"I

take you now to where there

is something a little more

tangible.

There

stand in the park of Creswell

Hall, near Stafford, the

ruins of a

little

thirteenth-century chapel. I will

describe what is left. I may

say

that

some twenty years ago I made

certain excavations, which

showed

the

ground plan to be still

complete. So far as I remember, we

found a

chamfered

plinth all round the

nave, with a west doorway.

The chancel

and

nave are of the same

width, the chancel measuring

about 21 ft.

long

and the nave c.

33

ft. The ground now again

covers much of what

we

found. The remains above

ground are those of the

chancel only.

Large

portions of the east and

north walls remain, and a

small part of

the

south wall. The north

wall is still c.

12

ft. high, and contains

two

narrow

lancets, quite perfect. The

east wall reaches c. 15

ft., and has a

good

base-mould. It contains the

opening, without the head,

of a three-

light

window, with simply moulded

jambs, and the

glass-line

remaining.

A string-course under the

window runs round the

angle

buttresses,

or rather did so run, for I

think the north buttress

has been

rebuilt,

and without the string. The

south buttress is complete up to

two

weatherings,

and has two strings round

it. It is a picturesque and

valuable

ruin, and well worth a

visit. It is amusing to notice

that

Creswell

now calls itself a rectory,

and an open-air service is

held

annually

within its walls. It was a

pre-bend of S. Mary's, Stafford,

and

previously

a Free Chapel, the advowson

belonging to the Lord of

the

Manor;

and it was sometimes supplied with

preachers from Ranton

Priory.

Of the story of its

destruction I can discover nothing. It is

now

carefully

preserved and, I have heard it suggested

that it might some

day

be rebuilt to meet the spiritual

needs of its

neighbourhood.

"We

pass now to the most

stately and beautiful object

in this

neighbourhood.

I mean the tower of Ranton

Priory Church. It is

always

known

here as Ranton Abbey. But it

has no right to the title.

It was an

off-shoot

of Haughmond Abbey, near Shrewsbury, and

was a Priory of

Black

Canons, founded temp.

Henry

II. The church has

disappeared

entirely,

with the exception of a bit

of the south-west walling of

the

nave

and a Norman doorway in it.

This may have connected

the church

with

the domestic buildings. In

Cough's Collection in the

Bodleian,

dated

1731, there is a sketch of

the church. What is shown

there is a

simple

parallelogram, with the

usual high walls, in

Transition-Norman

style,

with flat pilaster buttresses,

two strings running round

the walls,

the

upper one forming the

dripstones of lancet windows, a

corbel-table

supporting

the eaves-course, and a north-east priest's

door. But

whatever

the church may have

been (and the sketch

represents it as

being

of severe simplicity), some one

built on to it a west tower

of

great

magnificence. It is of early

Perpendicular date,

practically

uninjured,

the pinnacles only being

absent, though, happily, the

stumps

of

these remain. Its proportion

appears to me to be absolutely

perfect,

and

its detail so good that I

think you would have to

travel far to find

its

rival. There is a very

interesting point to notice in

the beautiful west

doorway.

It will be seen that the

masonry of the lower parts of

its

jambs

is quite different from that

of the upper parts, and there

can, I

think,

be no doubt that these lower

stones have been re-used

from a

thirteenth-century

doorway of some other part

of the buildings.

There

is

a tradition that the bells

of Gnosall Church were taken

from this

tower.

I can find no confirmation of this, and I

cannot believe it.

For

the

church at Gnosall is of earlier

date and greater magnificence

than

that

of Ranton Priory, and was, I

imagine, quite capable of

having bells

of

its own."

It

would be an advantage to arch�ology if

every one were such a

careful and

accurate

observer of local antiquarian

remains as the Rural Dean of

Stafford.

Wherever

we go we find similar deserted and

abandoned shrines. In

Derbyshire

alone

there are over a hundred

destroyed or disused churches, of

which Dr. Cox,

the

leading authority on the

subject, has published a

list. Nottinghamshire abounds

in

instances of the same kind. As

late as 1892 the church at

Colston Bassett was

deliberately

turned into a ruin. There

are only mounds and a few

stones to show the

site

of the parish church of

Thorpe-in-the-fields, which in the

seventeenth century

was

actually used as a beer-shop. In the

fields between Elston and

East Stoke is a

disused

church with a south Norman

doorway. The old parochial

chapel of

Aslacton

was long desecrated, and used in

comparatively recent days as a

beer-

shop.

The remains of it have,

happily, been reclaimed, and

now serve as a mission-

room.

East Anglia, famous for

its grand churches, has to

mourn over many

which

have

been lost, many that

are left roofless and

ivy-clad, and some ruined

indeed,

though

some fragment has been

made secure enough for

the holding of divine

service.

Whitling has a roofless

church with a round Norman

tower. The early

Norman

church of St. Mary at Kirby

Bedon has been allowed to

fall into decay, and

for

nearly two hundred years has

been ruinous. St. Saviour's

Church, Surlingham,

was

pulled down at the beginning

of the eighteenth century on

the ground that one

church

in the village was sufficient

for its spiritual wants, and

its materials served

to

mend roads.

A

strange reason has been

given for the destruction of

several of these East

Anglian

churches.

In Norfolk there were many

recusants, members of old Roman

Catholic

families,

who refused in the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries to obey

the law

requiring

them to attend their parish

church. But if their church

were in ruins no

service

could be held, and therefore

they could not be compelled

to attend. Hence

in

many cases the churches

were deliberately reduced to a ruinous

state. Bowthorpe

was

one of these unfortunate churches

which met its fate in

the days of Queen

Elizabeth.

It stands in a farm-yard, and

the nave made an excellent

barn and the

steeple

a dovecote. The lord of the

manor was ordered to restore it at the

beginning

of

the seventeenth century.

This he did, and for a

time it was used for

divine

service.

Now it is deserted and

roofless, and sleeps placidly

girt by a surrounding

wall,

a lonely shrine. The church

of St. Peter, Hungate, at

Norwich, is of great

historical

interest and contains good architectural

features, including a very

fine

roof.

It was rebuilt in the fifteenth

century by John Paston and

Margaret, his wife,

whose

letters form part of that

extraordinary series of medieval

correspondence

which

throws so much light upon

the social life of the

period. The church has

a

rudely

carved record of their work

outside the north door.

This unhappy church

has

fallen

into disuse, and it has been

proposed to follow the

example of the London

citizens

to unite the benefice with

another and to destroy the

building. Thanks to

the

energy and zeal of His

Highness Prince Frederick

Duleep Singh, delay

in

carrying

out the work of destruction

has been secured, and we

trust that his

efforts

to

save the building will be

crowned with the success

they deserve.

Not

far from Norwich are

the churches of Keswick and

Intwood. Before 1600

A.D.

the

latter was deserted and desecrated,

being used for a sheep-fold,

and the people

attended

service at Keswick. Then

Intwood was restored to its

sacred uses, and

poor

Keswick church was compelled to

furnish materials for its

repair. Keswick

remained

ruinous until a few years ago,

when part of it was restored and used as

a

cemetery

chapel. Ringstead has two

ruined churches, St.

Andrew's and St.

Peter's.

Only

the tower of the latter

remains. Roudham church two

hundred years ago was a

grand

building, as its remains

plainly testify. It had a

thatched roof, which was

fired

by

a careless thatcher, and has

remained roofless to this

day. Few are

acquainted

with

the ancient hamlet of

Liscombe, situated in a beautiful

Dorset valley. It now

consists

of only one or two houses, a little

Norman church, and an old

monastic

barn.

The little church is built

of flint, stone, and large

blocks of hard chalk,

and

consists

of a chancel and nave divided by a

Transition-Norman arch with

massive

rounded

columns. There are Norman

windows in the chancel, with

some later work

inserted.

A fine niche, eight feet

high, with a crocketed

canopy, stood at the

north-

east

corner of the chancel, but

has disappeared. The windows

of the nave and the

west

doorway have perished. It has

been for a long time

desecrated. The nave

is

used

as a bakehouse. There is a large open

grate, oven, and chimney in

the centre,

and

the chancel is a storehouse for

logs. The upper part of

the building has

been

converted

into an upper storey and

divided into bedrooms, which

have broken-

down

ceilings. The roof is of

thatch. Modern windows and a

door have been

inserted.

It is a deplorable instance of terrible

desecration.

The

growth of ivy unchecked has

caused many a ruin. The

roof of the nave and

south

aisle of the venerable church of

Chingford, Essex, fell a few

years ago

entirely

owing to the destructive ivy

which was allowed to work

its relentless will

on

the beams, tiles, and

rafters of this ancient

structure.

Besides

those we have mentioned there

are about sixty other

ruined churches in

Norfolk,

and in Suffolk many others,

including the magnificent

ruins of Covehithe,

Flixton,

Hopton, which was destroyed

only forty-four years ago

through the

burning

of its thatched roof, and

the Old Minster, South

Elmham.

Attempts

have been made by the

National Trust and the

Society for the

Protection

of

Ancient Buildings to save

Kirkstead Chapel, near Woodhall

Spa, Lincolnshire. It

is

one of the very few

surviving examples of the

capella

extra portas, which was

a

feature

of every Cistercian abbey,

where women and other

persons who were

not

allowed

within the gates could hear

Mass. The abbey was founded in

1139, and the

chapel,

which is private property, is one of

the finest examples of Early

English

architecture

remaining in the country. It is in a

very decaying condition. The

owner

has

been approached, and the officials of

the above societies have

tried to persuade

him

to repair it himself or to allow

them to do so. But these

negotiations have

hitherto

failed. It is very deplorable

when the owners of historic

buildings should

act

in this "dog-in-the-manger" fashion, and

surely the time has come

when the

Government

should have power to

compulsorily acquire such

historic monuments

when

their natural protectors

prove themselves to be incapable or

unwilling to

preserve

and save them from

destruction.

We

turn from this sorry

page of wilful neglect to one

that records the

grand

achievement

of modern antiquaries, the

rescue and restoration of the

beautiful

specimen

of Saxon architecture, the

little chapel of St.

Lawrence at Bradford-on-

Avon.

Until 1856 its existence was

entirely unknown, and the

credit of its

discovery

was due to the Rev. Canon

Jones, Vicar of Bradford. At

the Reformation

with

the dissolution of the abbey at

Shaftesbury it had passed into

lay hands. The

chancel

was used as a cottage. Round

its walls other cottages

arose. Perhaps part

of

the

building was at one time used as a

charnel-house, as in an old deed it is

called

the

Skull House. In 1715 the

nave and porch were

given to the vicar to be

used as a

school.

But no one suspected the

presence of this exquisite

gem of Anglo-Saxon

architecture,

until Canon Jones when

surveying the town from

the height of a

neighbouring

hill recognized the

peculiarity of the roof and

thought that it might

indicate

the existence of a church.

Thirty-seven years ago the

Wiltshire antiquaries

succeeded

in purchasing the building.

They cleared away the

buildings, chimney-

stacks,

and outhouses that had grown

up around it, and revealed

the whole beauties

of

this lovely shrine.

Arch�ologists have fought

many battles over it as to

its date.

Some

contend that it is the

identical church which

William of Malmesbury tells

us

St.

Aldhelm built at Bradford-on-Avon

about 700 A.D., others

assert that it cannot

be

earlier than the tenth

century. It was a monastic

cell attached to the Abbey

of

Malmesbury,

but Ethelred II gave it to the

Abbess of Shaftesbury in 1001 as a

secure

retreat for her nuns if

Shaftesbury should be threatened by the

ravaging

Danes.

We need not describe the

building, as it is well known.

Our artist has

furnished

us with an admirable illustration of

it. Its great height, its

characteristic

narrow

Saxon doorways, heavy plain

imposts, the string-courses

surrounding the

building,

the arcades of pilasters,

the carved figures of angels

are some of its

most

important

features. It is cheering to find

that amid so much that

has vanished we

have

here at Bradford a complete Saxon

church that differs very

little from what it

was

when it was first

erected.

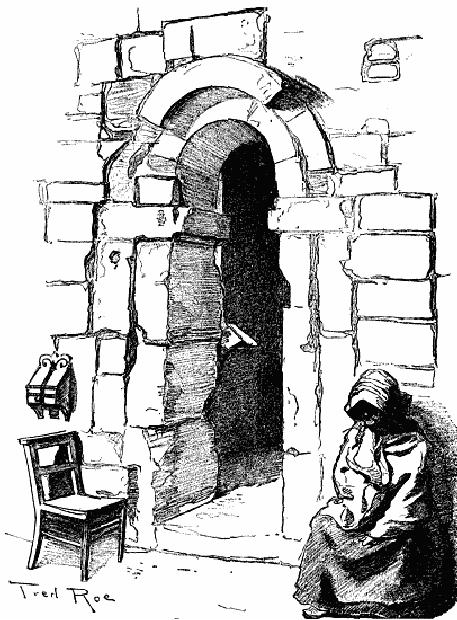

Saxon

Doorway in St. Lawrence's

Church, Bradford-on-Avon,

Wilts.

Other

Saxon remains are not

wanting. Wilfrid's Crypt at

Hexham, that at

Ripon,

Brixworth

Church, the church within

the precincts of Dover Castle,

the towers of

Barnack,

Barton-upon-Humber, Stow, Earl's

Barton, Sompting, Stanton

Lacy show

considerable

evidences of Saxon work. Saxon

windows with their peculiar

baluster

shafts

can be seen at Bolam and Billingham,

Durham; St. Andrew's,

Bywell,

Monkwearmouth,

Ovington, Sompting, St. Mary

Junior, York, Hornby,

Wickham

(Berks),

Waithe, Holton-le-Clay, Glentworth and

Clee (Lincoln), Northleigh,

Oxon,

and

St. Alban's Abbey. Saxon

arches exist at Worth,

Corhampton, Escomb,

Deerhurst,

St. Benet's, Cambridge,

Brigstock, and Barnack. Triangular

arches

remain

at Brigstock, Barnack, Deerhurst,

Aston Tirrold, Berks. We

have still some

Saxon

fonts at Potterne, Wilts;

Little Billing, Northants;

Edgmond and Bucknell,

Shropshire;

Penmon, Anglesey; and South

Hayling, Hants. Even Saxon

sundials

exist

at Winchester, Corhampton, Bishopstone,

Escomb, Aldborough, Edston, and

Kirkdale.

There is also one at Daglingworth,

Gloucestershire. Some hours of

the

Saxon's

day in that village must

have fled more swiftly

than others, as all the

radii

are

placed at the same angle.

Even some mural paintings by

Saxon artists exist

at

St.

Mary's, Guildford; St.

Martin's, Canterbury; and faint

traces at Britford,

Headbourne,

Worthing, and St. Nicholas,

Ipswich, and some painted

consecration

crosses

are believed to belong to

this period.

Recent

investigations have revealed

much Saxon work in our

churches, the

existence

of which had before been unsuspected.

Many circumstances

have

combined

to obliterate it. The Danish

wars had a disastrous effect on

many

churches

reared in Saxon times. The

Norman Conquest caused many

of them to be

replaced

by more highly finished

structures. But frequently, as we

study the history

written

in the stonework of our

churches, we find beneath coatings of

stucco the

actual

walls built by Saxon

builders, and an arch here, a

column there, which

link

our

own times with the

distant past, when England

was divided into eight

kingdoms

and

when Danegelt was levied to

buy off the marauding

strangers.

It

is refreshing to find these

specimens of early work in

our churches. Since

then

what

destruction has been

wrought, what havoc done

upon their fabric and

furniture!

At the Reformation iconoclasm

raged with unpitying

ferocity. Everybody

from

the King to the

churchwardens, who sold

church plate lest it should

fall into

the

hands of the royal commissioners,

seems to have been engaged

in pillaging

churches

and monasteries. The plunder of chantries

and guilds followed.

Fuller

quaintly

describes this as "the last

dish of the course, and

after cheese nothing is

to

be

expected." But the

coping-stone was placed on the vast

fabric of spoliation by

sending

commissioners to visit all

the cathedrals and parish churches, and

seize the

superfluous

plate and ornaments for the

King's use. Even quite

small churches

possessed

many treasures which the

piety of many generations had bestowed

upon

them.

There

is a little village in Berkshire

called Boxford, quite a

small place. Here is

the

list

of church goods which the

commissioners found there, and

which had escaped

previous

ravages:--

"One

challice, a cross of copper & gilt,

another cross of timber

covered

with

brass, one cope of blue

velvet embroidered with images of

angles,

one

vestment of the same suit

with an albe of Lockeram,22

two

vestments

of Dornexe,23

and three

other very old, two

old & coarse

albes

of Lockeram, two old copes

of Dornexe, iiij altar

cloths of linen

cloth,

two corporals with two

cases whereof one is embroidered,

two

surplices,

& one rochet, one bible & the

paraphrases of Erasmus in

English,

seven banners of lockeram & one streamer all

painted, three

front

cloths for altars whereof

one of them is with panes of

white

damask

& black satin, & the

other two of old vestments,

two towels of

linen,

iiij candlesticks of

latten24

& two

standertes25

before

the high

altar

of latten, a lent vail26

before

the high altar with

panes blue and

white,

two candlesticks of latten and

five branches, a peace,27

three

great

bells with one saunce bell

xx, one canopy of cloth, a covering

of

Dornixe

for the Sepulchre, two

cruets of pewter, a holy-water

pot of

latten,

a linen cloth to draw before

the rood. And all

the said parcels

safely

to be kept & preserved, & all the

same & every parcel

thereof to

be

forthcoming at all times

when it shall be of them

[the

churchwardens]

required."

This

inventory of the goods of one

small church enables us to

judge of the wealth

of

our country churches before

they were despoiled. Of private

spoliators their

name

was legion. The

arch-spoliator was Protector Somerset,

the King's uncle,

Edward

Seymour, formerly Earl of

Hertford and then created

Duke of Somerset. He

ruled

England for three years

after King Henry's death. He

was a glaring and

unblushing

church-robber, setting an example

which others were only

too ready to

follow.

Canon Overton28

tells

how Somerset House remains

as a standing memorial

of

his rapacity. In order to

provide materials for

building it he pulled down

the

church

of St. Mary-le-Strand and

three bishops' houses, and was proceeding

also to

pull

down the historical church

of St. Margaret, Westminster;

but public opinion

was

too strong against him, the

parishioners rose and beat

off his workmen, and

he

was

forced to desist, and

content himself with

violating and plundering

the

precincts

of St. Paul's. Moreover, the

steeple and most of the

church of St. John of

Jerusalem,

Smithfield, were mined and

blown up with gunpowder that

the materials

might

be utilized for the ducal

mansion in the Strand. He

turned Glastonbury,

with

all

its associations dating from

the earliest introduction of

Christianity into our

island,

into a worsted manufactory,

managed by French Protestants. Under

his

auspices

the splendid college of St.

Martin-le-Grand in London was converted

into

a

tavern, and St. Stephen's Chapel,

Westminster, served the scarcely

less

incongruous

purpose of a Parliament House. All this

he did, and when his

well-

earned

fall came the Church

fared no better under his

successor, John Dudley,

Earl

of

Warwick, and afterwards Duke

of Northumberland.

Another

wretch was Robert, Earl of Sussex, to

whom the King gave the

choir of

Atleburgh,

in Norfolk, because it belonged to a

college. "Being of a

covetous

disposition,

he not only pulled down and

spoiled the chancel, but

also pulled up

many

fair marble gravestones of his

ancestors with monuments of

brass upon them,

and

other fair good pavements, and

carried them and laid them

for his hall,

kitchen,

and

larder-house." The church of

St. Nicholas, Yarmouth, has

many monumental

stones,

the brasses of which were in

1551 sent to London to be cast into

weights

and

measures for the use of

the town. The shops of

the artists in brass in

London

were

full of broken brass memorials

torn from tombs. Hence

arose the making of

palimpsest

brasses, the carvers using

an old brass and on the reverse

side cutting a

memorial

of a more recently deceased

person.

After

all this iconoclasm,

spoliation, and robbery it is

surprising that anything

of

value

should have been left in

our churches. But happily

some treasures escaped,

and

the gifts of two or three

generations added others. Thus I

find from the will of

a

good

gentleman, Mr. Edward Ball,

that after the spoliation of

Barkham Church he

left

the sum of five shillings

for the providing of a processional

cross to be borne

before

the choir in that church,

and I expect that he gave us our

beautiful

Elizabethan

chalice of the date 1561.

The Church had scarcely

recovered from its

spoliation

before another era of

devastation and robbery

ensued. During the

Cromwellian

period much destruction was

wrought by mad zealots of the

Puritan

faction.

One of these men and his

doings are mentioned by Dr.

Berwick in his

Querela

Cantabrigiensis:--

"One

who calls himself John

[it should be William]

Dowsing and by

Virtue

of a pretended Commission, goes about

ye country like a

Bedlam,

breaking glasse windows,

having battered and beaten

downe

all

our painted glasses, not

only in our Chappels, but

(contrary to

order)

in our Publique Schools,

Colledge Halls, Libraries,

and

Chambers,

mistaking, perhaps, ye liberall

Artes for Saints (which

they

intend

in time to pull down too)

and having (against an order)

defaced

and

digged up ye floors of our Chappels,

many of which had lien so

for

two

or three hundred years together,

not regarding ye dust of our

founders

and predecessors who likely

were buried there; compelled

us

by

armed Souldiers to pay forty

shillings a Colledge for not

mending

what

he had spoyled and defaced, or forth

with to goe to

prison."

We

meet with the sad doings of

this wretch Dowsing in

various places in

East

Anglia.

He left his hideous mark on

many a fair church. Thus

the churchwardens of

Walberswick,

in Suffolk, record in their

accounts:--

"1644,

April 8th, paid to Martin

Dowson, that came with

the troopers

0

6 0."

to

our church, about the

taking down of Images and

Brasses off Stones

"1644

paid that day to others for

taking up the brasses of

grave stones

0

1 0."

before

the officer Dowson

came

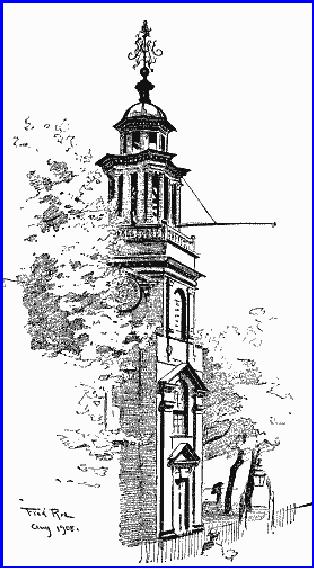

St.

George's Church, Great

Yarmouth

The

record of the ecclesiastical exploits of

William Dowsing has been

preserved by

the

wretch himself in a diary

which he kept. It was published in

1786, and the

volume

provides much curious

reading. With reference to

the church of Toffe

he

says:--

"Will:

Disborugh Church Warden

Richard Basly and John

Newman

Cunstable,

27 Superstitious pictures in glass and

ten other in stone,

three

brass inscriptions, Pray for

ye Soules, and

a Cross to be taken of

the

Steeple (6s. 8d.) and there

was divers Orate pro

Animabus in ye

windows,

and on a Bell, Ora pro Anima

Sanct� Catharin�."

"Trinity

Parish, Cambridge, M. Frog,

Churchwarden, December 25,

we

brake down 80 Popish pictures, and one of

Christ and God ye

Father

above."

"At

Clare

we

brake down 1000 pictures

superstitious."

"Cochie,

there were divers pictures

in the Windows which we

could

not

reach, neither would they

help us to raise the

ladders."

"1643,

Jany 1, Edwards parish, we digged up

the steps, and brake

down

40

pictures, and took off ten

superstitious inscriptions."

It

is terrible to read these records,

and to imagine all the

beautiful works of art

that

this

ignorant wretch ruthlessly

destroyed. To all the

inscriptions on tombs

containing

the pious petition Orate

pro anima--his

ignorance is palpably

displayed

by

his Orate

pro animabus--he paid special

attention. Well did Mr. Cole

observe

concerning

the last entry in Dowsing's

diary:--

"From

this last Entry we may

clearly see to whom we are

obliged for

the

dismantling of almost all

the gravestones that had brasses on

them,

both

in town and country: a

sacrilegious sanctified rascal that

was

afraid,

or too proud, to call it St.

Edward's Church, but not

ashamed to

rob

the dead of their honours

and the Church of its

ornaments. W.C."

He

tells also of the dreadful

deeds that were being done

at Lowestoft in 1644:--

"In

the same year, also, on

the 12th of June, there came

one Jessop,

with

a commission from the Earl

of Manchester, to take away

from

gravestones

all inscriptions on which he

found Orate

pro anima--a

wretched

Commissioner not able to read or

find out that which

his

commission

enjoyned him to remove--he

took up in our Church

so

much

brasse, as he sold to Mr. Josiah

Wild for five shillings,

which

was

afterwards (contrary to my knowledge)

runn into the little

bell that

hangs

in the Town-house. There

were taken up in the Middle

Ayl

twelve

pieces belonging to twelve generations of

the Jettours."

The

same scenes were being

enacted in many parts of England.

Everywhere

ignorant

commissioners were rampaging

about the country imitating

the ignorant

ferocity

of this Dowsing and Jessop.

No wonder our churches were

bare, pillaged,

and

ruinated. Moreover, the

conception of art and the

taste for architecture

were

dead

or dying, and there was no one who

could replace the beautiful

objects which

these

wretches destroyed or repair

the desolation they had

caused.

Another

era of spoliation set in in

more recent times, when

the restorers came

with

vitiated

taste and the worst ideals to

reconstruct and renovate our

churches which

time,

spoliation, and carelessness had left

somewhat the worse for

wear. The

Oxford

Movement taught men to

bestow more care upon

the houses of God in

the

land,

to promote His honour by

more reverent worship, and

to restore the beauty of

His

sanctuary. A rector found

his church in a dilapidated

state and talked over

the

matter

with the squire. Although

the building was in a sorry

condition, with a

cracked

ceiling, hideous galleries, and

high pews like cattle-pens, it had a

Norman

doorway,

some Early English carved

work in the chancel, a good

Perpendicular

tower,

and fine Decorated windows. These two

well-meaning but ignorant

men

decided

that a brand-new church

would be a great improvement on this

old tumble-

down

building. An architect was called

in, or a local builder; the

plan of a new

church

was speedily drawn, and ere

long the hammers and

axes were let loose

on

the

old church and every vestige

of antiquity destroyed. The

old Norman font

was

turned

out of the church, and

either used as a cattle-trough or to

hold a flower-pot

in

the rectory garden. Some of

the beautifully carved

stones made an

excellent

rockery

in the squire's garden, and old

woodwork, perchance a

fourteenth-century

rood-screen,

encaustic tiles bearing the

arms of the abbey with which in

former

days

the church was connected,

monuments and stained glass, are all

carted away

and

destroyed, and the triumph of

vandalism is complete.

That

is an oft-told tale which

finds its counterpart in

many towns and villages,

the

entire

and absolute destruction of the

old church by ignorant

vandals who work

endless

mischief and know not

what they do. There is

the village of Little

Wittenham,

in our county of Berks, not

far from Sinodun Hill, an

ancient earthwork

covered

with trees, that forms so

conspicuous an object to the

travellers by the

Great

Western Railway from Didcot

to Oxford. About forty years

ago terrible

things

were done in the church of

that village. The vicar was

a Goth. There was a

very

beautiful chantry chapel on

the south side of the

choir, full of magnificent

marble

monuments to the memory of

various members of the Dunce

family. This

family,

once great and powerful, whose great house stood

hard by on the north

of

the

church--only the terraces of

which remain--is now, it is

believed, extinct.

The

vicar

thought that he might be

held responsible for the

dilapidations of this

old

chantry;

so he pulled it down, and broke

all the marble tombs

with axes and

hammers.

You can see the shattered

remains that still show

signs of beauty in one

of

the adjoining barns. Some

few were set up in the

tower, the old font

became a

pig-trough,

the body of the church was

entirely renewed, and vandalism

reigned

supreme.

In our county of Berks there

were at the beginning of the

last century 170

ancient

parish churches. Of these, thirty

have been pulled down

and entirely rebuilt,

six

of them on entirely new sites; one

has been burnt down, one

disused; before

1890

one hundred were restored, some of

them most drastically, and

several others

have

been restored since, but

with greater respect to old

work.

A

favourite method of "restoration" was

adopted in many instances. A church had

a

Norman

doorway and pillars in the

nave; sundry additions and

alterations had been

made

in subsequent periods, and examples of Early

English, Decorated, and

Perpendicular

styles of architecture were

observable, with, perhaps, a

Renaissance

porch

or other later feature. What

did the early restorers do?

They said, "This is a

Norman

church; all its details

should be Norman too." So

they proceeded to take

away

these later additions and

imitate Norman work as much

as they could by

breaking

down the Perpendicular or Decorated

tracery in the windows and

putting

in

large round-headed windows--their

conception of Norman work,

but far

different

from what any Norman

builder would have

contrived. Thus these

good

people

entirely destroyed the

history of the building, and

caused to vanish much

that

was interesting and important.

Such is the deplorable story

of the "restoration"

of

many a parish church.

An

amusing book, entitled

Hints to

Some Churchwardens, with a

few Illustrations

Relative

to the Repair and Improvement of Parish

Churches, was

published in

1825.

The author, with much

satire, depicts the "very many

splendid, curious, and

convenient

ideas which have emanated

from those churchwardens who

have

attained

perfection as planners and architects."

He apologises for not giving

the

names

of these superior men and

the dates of the

improvements they have

achieved,

but

is sure that such works as

theirs must immortalize

them, not only in

their

parishes,

but in their counties, and,

he trusts, in the kingdom at

large. The following

are

some of the

"hints":--

"How to

affix a porch to an old

church.

"If

the church is of stone, let

the porch be of brick, the

roof slated, and

the

entrance to it of the improved

Gothic called modern, being

an arch

formed

by an acute angle. The porch

should be placed so as to stop up

what

might be called a useless

window; and as it sometimes

happens

that

there is an ancient

Saxon29

entrance,

let it be carefully bricked

up,

and

perhaps plastered, so as to conceal as

much as possible of the

zigzag

ornament used in buildings of

this kind. Such

improvements

cannot

fail to ensure celebrity to churchwardens

of future ages.

"How to add

a vestry to an old

church.

"The

building here proposed is to be of bright

brick, with a slated

roof

and

sash windows, with a small

door on one side; and it is,

moreover,

to

be adorned with a most tasty

and ornamental brick

chimney, which

terminates

at the chancel end. The

position of the building

should be

against

two old Gothic windows;

which, having the advantage

of

hiding

them nearly altogether, when

contrasted with the dull

and

uniform

surface of an old stone church,

has a lively and most

imposing

effect.

"How to

ornament the top or battlements of a

tower belonging to an

ancient

church.

"Place

on each battlement, vases,

candlesticks, and pineapples

alternately,

and the effect will be striking.

Vases have many

votaries

amongst

those worthy members of society, the

churchwardens.

Candlesticks

are of ancient origin, and

represent, from the

highest

authority,

the light of the churches:

but as in most

churches

weathercocks

are used, I would here recommend

the admirers of

novelty

and improvement to adopt a pair of

snuffers, which might

also

be

considered as a useful emblem for

reinvigorating the lights

from the

candlesticks.

The pineapple ornament

having in so many

churches

been

judiciously substituted for

Gothic, cannot fail to

please. Some

such

ornament should also be placed at the

top of the church, and at

the

chancel

end. But as this publication

does not restrict any

churchwarden

of

real taste, and as the ornaments here

recommended are in a common

way

made of stone, if any would

wish to distinguish his year

of office,

perhaps

he would do it brilliantly by painting

them all bright

red...."

Other

valuable suggestions are made in

this curious and amusing

work, such as

"how

to repair Quartre-feuille windows" by

cutting out all the

partitions and

making

them quite round; "how to

adapt a new church to an old

tower with most

taste

and effect," the most

attractive features being

light iron partitions instead

of

stone

mullions for the windows,

with shutters painted

yellow, bright brick

walls

and

slate roof, and a door painted

sky-blue. You can best

ornament a chancel by

placing

colossal figures of Moses and Aaron

supporting the altar, huge

tables of the

commandments,

and clusters of grapes and pomegranates

in festoons and clusters

of

monuments. Vases upon

pillars, the commandments in

sky-blue, clouds

carved

out

of wood supporting angels, are

some of the ideas

recommended. Instead of a

Norman

font you can substitute one

resembling a punch-bowl,30

with

the pedestal

and

legs of a round claw table; and it

would be well to rear a massive pulpit in

the

centre

of the chancel arch, hung

with crimson and gold lace,

with gilt

chandeliers,

large

sounding-board with a vase at

the top. A stove is always

necessary. It can be

placed

in the centre of the

chancel, and the stove-pipe can be

carried through the

upper

part of the east window,

and then by an elbow

conveyed to the crest of

the

roof

over the window, the

cross being taken down to

make room for the

chimney.

Such

are some of the

recommendations of this ingenious

writer, which are

ably

illustrated

by effective drawings. They

are not all imaginative.

Many old churches

tell

the tragic story of their

mutilation at the hands of a rector

who has discovered

Parker's

Glossary,

knows nothing about art,

but "does know what he

likes," advised

by

his wife who has

visited some of the

cathedrals, and by an architect who

has

been

elaborately educated in the

principles of Roman Renaissance,

but who knows

no

more of Lombard, Byzantine, or

Gothic art than he does of

the dynasties of

ancient

Egypt. When a church has

fallen into the hands of

such renovators and

been

heavily

"restored," if the ghost of one of

its medieval builders came

to view his

work

he would scarcely recognize

it. Well says Mr. Thomas

Hardy: "To restore the

great

carcases of medi�valism in the

remote nooks of western

England seems a not

less

incongruous act than to set

about renovating the

adjoining crags

themselves,"

and

well might he sigh over

the destruction of the grand

old tower of

Endelstow

Church

and the erection of what the

vicar called "a splendid

tower, designed by a

first-rate

London man--in the newest

style of Gothic art and full of

Christian

feeling."

The

novelist's remarks on "restoration"

are most valuable:--

"Entire

destruction under the saving

name has been effected on

so

gigantic

a scale that the protection

of structures, their being

kept wind

and

weather-proof, counts as nothing in

the balance. Its

enormous

magnitude

is realized by few who have

not gone personally

from

parish

to parish through a considerable

district, and compared existing

churches

there with records, traditions, and

memories of what they

formerly

were. The shifting of old

windows and other

details

irregularly

spaced, and spacing them at exact

distances, has been one

process.

The deportation of the

original chancel arch to an

obscure

nook

and the insertion of a wider

new one, to throw open the

view of

the

choir, is a practice by no means

extinct. Next in turn to the

re-

designing

of old buildings and parts of them

comes the devastation

caused

by letting restorations by contract,

with a clause in the

specification

requesting the builder to

give a price for 'old

materials,'

such

as the lead of the roofs, to be replaced

by tiles or slates, and the

oak

of the pews, pulpit,

altar-rails, etc., to be replaced by deal.

Apart

from

these irregularities it has

been a principle that

anything later than

Henry

VIII is anathema and to be cast out. At

Wimborne Minster fine

Jacobean

canopies have been removed

from Tudor stalls for

the

offence

only of being Jacobean. At a

hotel in Cornwall a tea-garden

was,

and probably is still, ornamented

with seats constructed of

the

carved

oak from a neighbouring church--no

doubt the restorer's

perquisite.

"Poor

places which cannot afford

to pay a clerk of the works

suffer

much

in these ecclesiastical convulsions. In one

case I visited, as a

youth,

the careful repair of an

interesting Early English

window had

been

specified, but it was gone.

The contractor, who had met

me on the

spot,

replied genially to my gaze of

concern: 'Well, now, I said

to

myself

when I looked at the old

thing, I won't stand upon a

pound or

two.

I'll give 'em a new winder

now I am about it, and make a good

job

of

it, howsomever.' A caricature in

new stone of the old window

had

taken

its place. In the same

church was an old oak rood-screen in

the

Perpendicular

style with some gilding and

colouring still

remaining.

Some

repairs had been specified, but I

beheld in its place a new

screen

of

varnished deal. 'Well,'

replied the builder, more

genial than ever,

'please

God, now I am about it, I'll

do the thing well, cost what

it will.'

The

old screen had been used up

to boil the work-men's

kettles, though

'a

were not much at

that.'"

Such

is the terrible report of

this amazing

iconoclasm.

Some

wiseacres, the vicar and

churchwardens, once determined to pull

down their

old

church and build a new

one. So they met in solemn

conclave and passed

the

following

sagacious resolutions:--

1.

That a new church should be

built.

2.

That the materials of the

old church should be used in

the

construction

of the new.

3.

That the old church

should not be pulled down

until the new one be

built.

How

they contrived to combine

the second and third

resolutions history

recordeth

not.

Even

when the church was spared

the "restorers" were guilty

of strange enormities

in

the embellishment and

decoration of the sacred

building. Whitewash

was

vigorously

applied to the walls and

pews, carvings, pulpit, and

font. If curious

mural

paintings adorned the walls,

the hideous whitewash soon

obliterated every

trace

and produced "those modest hues which

the native appearance of the

stone so

pleasingly

bestows." But whitewash has

one redeeming virtue, it preserves

and

saves

for future generations treasures

which otherwise might have

been destroyed.

Happily

all decoration of churches

has not been carried

out in the reckless

fashion

thus

described by a friend of the

writer. An old Cambridgeshire

incumbent, who

had

done nothing to his church

for many years, was bidden

by the archdeacon to

"brighten

matters up a little." The

whole of the woodwork wanted

repainting and

varnishing,

a serious matter for a poor

man. His wife, a very

capable lady, took

the

matter

in hand. She went to the

local carpenter and wheelwright and

bought up the

whole

of his stock of that

particular paint with which

farm carts and wagons

are

painted,

coarse but serviceable, and of

the brightest possible red, blue, green,

and

yellow

hues. With her own hands she

painted the whole of the

interior--pulpit,

pews,

doors, etc., and probably the

wooden altar, using the

colours as her fancy

dictated,

or as the various colours

held out. The effect was

remarkable. A

succeeding

rector began at once the

work of restoration, scraping

off the paint and

substituting

oak varnish; but when my

friend took a morning

service for him

the

work

had not been completed, and

he preached from a bright green

pulpit.

Carving

on Rood-screen, Alcester Church,

Warwick

The

contents of our parish

churches, furniture and plate,

are rapidly

vanishing.

England

has ever been remarkable

for the number and beauty of

its rood-screens.

At

the Reformation the roods

were destroyed and many

screens with them,

but

many

of the latter were retained,

and although through neglect or

wanton

destruction

they have ever since been

disappearing, yet hundreds still

exist.31

Their

number

is, however, sadly

decreased. In Cheshire "restoration"

has removed nearly

all

examples, except Ashbury,

Mobberley, Malpas, and a few

others. The churches

of

Bunbury and Danbury have

lost some good screen-work since

1860. In

Derbyshire

screens suffered severely in

the nineteenth century, and

the records of

each

county show the

disappearance of many notable

examples, though

happily

Devonshire,

Somerset, and several other shires still

possess some

beautiful

specimens

of medieval woodwork. A large

number of Jacobean pulpits

with their

curious

carvings have vanished. A

pious donor wishes to give a

new pulpit to a

church

in memory of a relative, and the

old pulpit is carted away to make

room for

its

modern and often inferior

substitute. Old stalls and

misericordes, seats and

benches

with poppy-head terminations

have often been made to

vanish, and the

pillaging

of our churches at the

Reformation and during the

Commonwealth period

and

at the hands of the "restorers"

has done much to deprive our

churches of their

ancient

furniture.

Most

churches had two or three

chests or coffers for the

storing of valuable

ornaments

and vestments. Each chantry had

its chest or ark, as it was

sometimes

called,

e.g. the collegiate church of

St. Mary, Warwick, had in

1464, "ij old

irebound

coofres," "j gret olde arke to

put in vestments," "j olde arke at

the autere

ende,

j old coofre irebonde having

a long lok of the olde

facion, and j lasse

new

coofre

having iij loks called

the tresory cofre and

certain almaries." "In the

inner

house

j new hie almarie with ij

dores to kepe in the

evidence of the Churche and

j

great

old arke and certain olde

Almaries, and in the house afore

the Chapter house j

old

irebounde cofre having hie

feet and rings of iron in

the endes thereof to heve

it

bye."

"It

is almost exceptional to find

any parish of five hundred

inhabitants

which

does not possess a parish

chest. The parish chest of

the parish in

which

I am writing is now in the

vestry of the church here.

It has been

used

for generations as a coal box. It is

exceptional to find anything

so

useful

as wholesome fuel inside

these parish chests; their

contents have

in

the great majority of instances utterly

perished, and the miserable

destruction

of those interesting parish records

testifies to the

almost

universal

neglect which they have

suffered at the hands, not

of the

parsons,

who as a rule have kept

with remarkable care the

register

books

for which they have

always been responsible, but

of the

churchwardens

and overseers, who have let

them perish without a

thought

of their value.

"As

a rule the old parish

chests have fallen to

pieces, or worse, and

their

contents have been used to

light the church stove,

except in those

very

few cases where the

chests were furnished with

two or more keys,

each

key being of different wards

from the other, and

each being

handed

over to a different functionary

when the time of the

parish

meeting

came round."32

When

the ornaments and vestments

were carted away from the

church in the time

of

Edward VI, many of the

church chests lost their

use, and were sold or

destroyed,

the

poorest only being kept for

registers and documents. Very magnificent

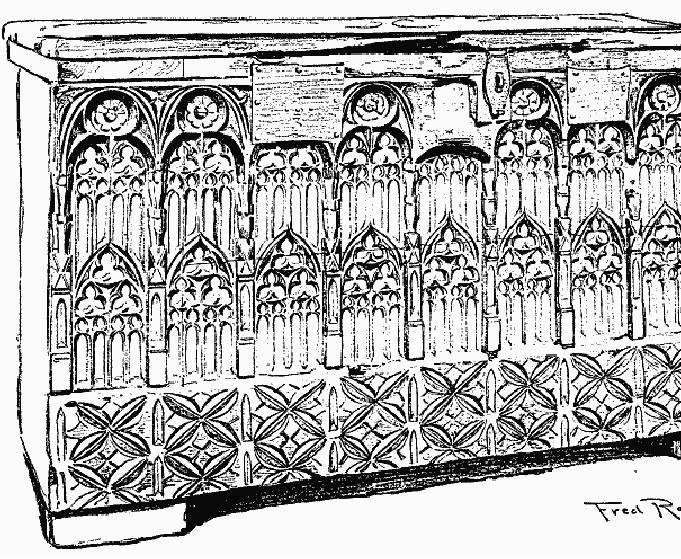

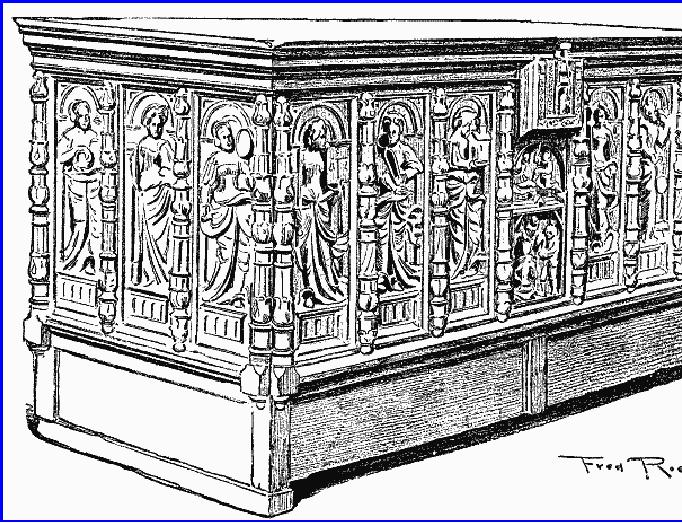

were

some

of these chests which have

survived, such as that at

Icklington, Suffolk,

Church

Brampton, Northants, Rugby,

Westminster Abbey, and Chichester.

The old

chest

at Heckfield may have been

one of those ordered in the reign of King

John for

the

collection of the alms of

the faithful for the

fifth crusade. The artist, Mr.

Fred

Roe,

has written a valuable work

on chests, to which those who desire to

know

about

these interesting objects

can refer.

Another

much diminishing store of treasure

belonging to our churches is

the church

plate.

Many churches possess some

old plate--perhaps a pre-Reformation

chalice.

It

is worn by age, and the

clergyman, ignorant of its

value, takes it to a jeweller

to

be

repaired. He is told that it is old

and thin and cannot easily

be repaired, and is

offered

very kindly by the jeweller

in return for this old

chalice a brand-new one

with

a paten added. He is delighted, and

the old chalice finds

its way to

Christie's,

realizes

a large sum, and goes into

the collection of some

millionaire. Not long

ago

the

Council of the Society of

Antiquaries issued a memorandum to

the bishops and

archdeacons

of the Anglican Church

calling attention to the

increasing frequency of

the

sale of old or obsolete church

plate. This is of two kinds:

(1) pieces of plate

or

other

articles of a domestic character not

especially made, nor perhaps

well fitted

for

the service of the Church;

(2) chalices, patens, flagons, or

plate generally, made

especially

for ecclesiastical use, but

now, for reasons of change of

fashion or from

the

articles themselves being

worn out, no longer desired

to be used. A church

possibly

is in need of funds for

restoration, and an effort is naturally

made to turn

such

articles into money. The

officials decide to sell any

objects the church

may

have

of the first kind. Thus

the property of the Church

of England finds its

way

abroad,

and is thus lost to the

nation. With regard to the

sacred vessels of the

second

class, it is undignified, if not a

desecration, that vessels of such a

sacred

character

should be subjected to a sale by

auction and afterwards used as

table

ornaments

by collectors to whom their

religious significance makes no

appeal. We

are

reminded of the profanity of

Belshazzar's feast.33

It would be

far better to place

such

objects for safe custody

and preservation in some

local museum. Not long

ago

a

church in Knightsbridge was removed

and rebuilt on another site. It had

a

communion

cup presented by Archbishop

Laud. Some addition was

required for the

new

church, and it was proposed to

sell the chalice to help in

defraying the cost of

this

addition. A London dealer offered

five hundred guineas for it,

and doubtless by

this

time it has passed into

private hands and left the

country. This is only

one

instance

out of many of the depletion

of the Church of its treasures. It

must not be

forgotten

that although the vicar

and churchwardens are for

the time being

trustees

of

the church plate and

furniture, yet the property

really is vested in the

parishioners.

It ought not to be sold

without a faculty, and the

chancellors of

dioceses

ought to be extremely careful

ere they allow such

sales to take place.

The

learned

Chancellor of Exeter very

wisely recently refused to

allow the rector of

Churchstanton

to sell a chalice of the

date 1660 A.D., stating that

it was painfully

repugnant

to the feelings of many

Churchmen that it should be possible

that a

vessel

dedicated to the most sacred

service of the Church should

figure upon the

dinner-table

of a collector. He quoted a case of a

chalice which had

disappeared

from

a church and been found

afterwards with an inscription

showing that it had

been

awarded as a prize at athletic sports.

Such desecration is too deplorable

for

words

suitable to describe it. If

other chancellors took the

same firm stand as Mr.

Chadwyck-Healey,

of Exeter, we should hear less of

such alienation of

ecclesiastical

treasure.

Fourteenth-century

Coffer in Faversham Church,

Kent From Old

Oak Furniture, by

Fred

Roe

Flanders

Chest in East Dereham Church,

Norfolk, temp.

Henry

VIII From Old

Oak

Furniture

Another

cause of mutilation and the

vanishing of objects of interest

and beauty is

the

iconoclasm of visitors, especially of

American visitors, who love

our English

shrines

so much that they like to

chip off bits of statuary or

wood-carving to

preserve

as mementoes of their visit. The

fine monuments in our

churches and

cathedrals

are especially convenient to

them for prey. Not

long ago the

best

portions

of some fine carving were

ruthlessly cut and hacked away by a

party of

American

visitors. The verger

explained that six of the

party held him in

conversation

at one end of the building while

the rest did their deadly

and nefarious

work

at the other. One of the

most beautiful monuments in

the country, that of

the

tomb

of Lady Maud FitzAlan at

Chichester, has recently

been cut and chipped

by

these

unscrupulous visitors. It may be

difficult to prevent them

from damaging such

works

of art, but it is hoped that

feelings of greater reverence may

grow which

would

render such vandalism

impossible. All civilized persons

would be ashamed

to

mutilate the statues of

Greece and Rome in our

museums. Let them realize

that

these

monuments in our cathedrals and churches

are just as valuable, as

they are the

best

of English art, and then no

sacrilegious hand would dare

to injure them or

deface

them by scratching names

upon them or by carrying

away broken chips as

souvenirs.

Playful boys in churchyards sometimes do

much mischief. In

Shrivenham

churchyard there is an ancient

full-sized effigy, and two

village urchins

were

recently seen amusing

themselves by sliding the

whole length of the

figure.

This

must be a common practice of

the boys of the village, as

the effigy is worn

almost

to an inclined plane. A tradition

exists that the figure

represents a man

who

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION