|

OLD CASTLES |

| << IN STREETS AND LANES |

| VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES >> |

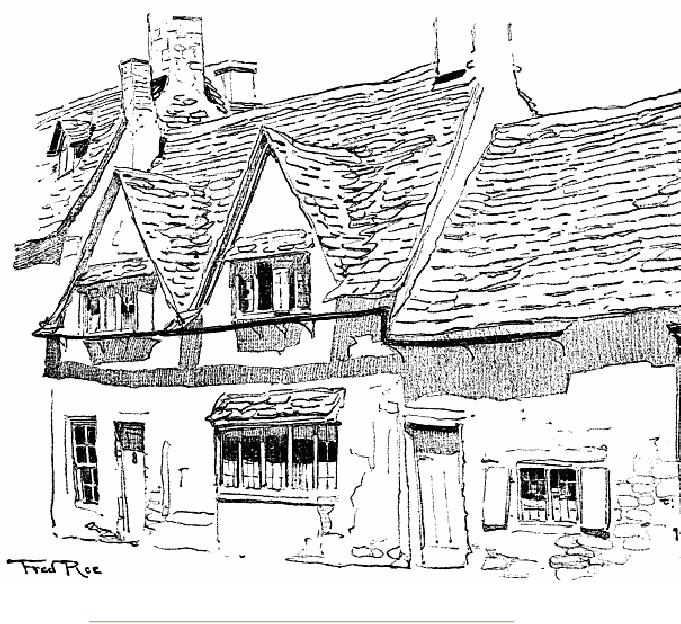

Wilney

Street Burford

CHAPTER

V

OLD

CASTLES

Castles

have played a prominent part

in the making of England.

Many towns owe

their

existence to the protecting

guard of an old fortress.

They grew up beneath

its

sheltering

walls like children holding

the gown of their good

mother, though the

castle

often proved but a harsh and

cruel stepmother, and exacted heavy

tribute in

return

for partial security from

pillage and rapine. Thus

Newcastle-upon-Tyne

arose

about the early fortress

erected in 1080 by Robert Curthose to

guard the

passage

of the river at the Pons

Aelii. The poor little

Saxon village of

Monkchester

was

then its neighbour. But

the castle occupying a fine

strategic position soon

attracted

townsfolk, who built their

houses 'neath its shadow.

The town of

Richmond

owes its existence to the

lordly castle which Alain

Rufus, a cousin of

the

Duke

of Brittany, erected on land

granted to him by the

Conqueror. An old

rhyme

tells

how he

Came

out of Brittany

With

his wife Tiffany,

And

his maid Manfras,

And

his dog Hardigras.

He

built his walls of stone. We

must not imagine, however,

that an early Norman

castle

was always a vast keep of stone.

That came later. The

Normans called their

earliest

strongholds mottes,

which consisted of a mound with

stockades and a deep

ditch

and a bailey-court also defended by a ditch and

stockades. Instead of the

great

stone

keep of later days,

"foursquare to every wind

that blew," there was a

wooden

tower

for the shelter of the

garrison. You can see in the

Bayeux tapestry the

followers

of William the Conqueror in

the act of erecting some

such tower of

defence.

Such structures were

somewhat easily erected, and did

not require a long

period

for their construction.

Hence they were very

useful for the holding of

a

conquered

country. Sometimes advantage was taken of

the works that the

Romans

had

left. The Normans made

use of the old stone walls

built by the earliest

conquerors

of Britain. Thus we find at Pevensey a

Norman fortress born within

the

ancient

fortress reared by the

Romans to protect that

portion of the southern

coast

from

the attacks of the northern pirates.

Porchester Keep rose in the time of

the first

Henry

at the north-west angle of

the Roman fort. William I

erected his castle at

Colchester

on the site of the Roman

castrum.

The old Roman wall of

London was

used

by the Conqueror for the

eastern defence of his Tower

that he erected to

keep

in

awe the citizens of the

metropolis, and at Lincoln and Colchester

the works of

the

first conquerors of Britain

were eagerly utilized by

him.

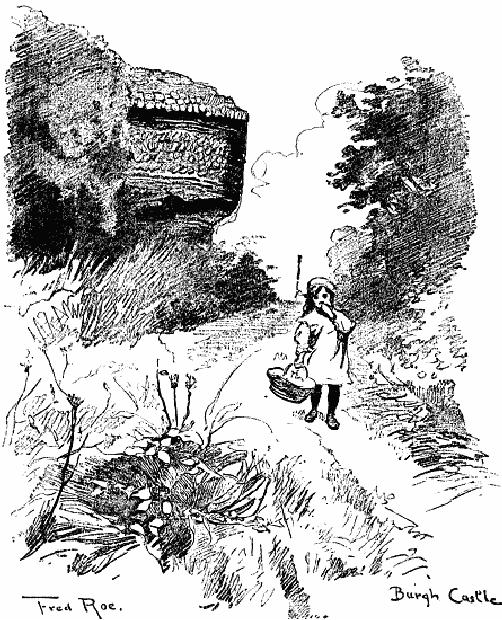

One

of the most important Roman

castles in the country is

Burgh Castle, in North

Suffolk,

with its grand and noble

walls. The late Mr. G.E.

Fox thus described

the

ruins:--

"According

to the plan on the Ordnance

Survey map, the walls

enclose

a

quadrangular area roughly 640

feet long by 413 wide, the

walls being

9

feet thick with a foundation

12 feet in width. The angles of

the

station

are rounded. The eastern

wall is strengthened by four

solid

bastions,

one standing against each of the

rounded angles, the

other

two

intermediate, and the north and

south sides have one each,

neither

of

them being in the centre of

the side, but rather

west of it. The

quaggy

ground between the camp and

the stream would be an

excellent

defence

against sudden attack."

Burgh

Castle

Burgh

Castle, according to the late

Canon Raven, was the

Roman station

Gariannonum

of

the Notitia

Imperii. Its

walls are built of

flint-rubble concrete, and

there

are lacing courses of tiles.

There is no wall on the

west, and Canon Raven

used

to contend that one existed

there but has been

destroyed. But this

conjecture

seems

improbable. That side was

probably defended by the sea,

which has

considerably

receded. Two gates remain,

the principal one being the

east gate,

commanded

by towers a hundred feet

high; while the north is a

postern-gate about

five

feet wide. The Romans

have not left many

traces behind them. Some

coins

have

been found, including a

silver one of Gratian and

some of Constantine.

Here

St.

Furseus, an Irish missionary, is said to

have settled with a colony

of monks,

having

been favourably received by Sigebert,

the ruler of the East

Angles, in 633

A.D.

Burgh Castle is one of the finest

specimens of a Roman fort

which our earliest

conquerors

have left us, and ranks

with Reculver, Richborough, and

Pevensey,

those

strong fortresses which were

erected nearly two thousand

years ago to guard

the

coasts against foreign

foes.

In

early days, ere Norman and

Saxon became a united

people, the castle was

the

sign

of the supremacy of the

conquerors and the subjugation of

the English. It kept

watch

and ward over tumultuous

townsfolk and prevented any

acts of rebellion and

hostility

to their new masters. Thus

London's Tower arose to keep

the turbulent

citizens

in awe as well as to protect

them from foreign foes.

Thus at Norwich the

castle

dominated the town, and

required for its erection

the destruction of over

a

hundred

houses. At Lincoln the Conqueror

destroyed 166 houses in order

to

construct

a strong motte

at

the south-west corner of the

old castrum

in

order to

overawe

the city. Sometimes castles

were erected to protect the

land from foreign

foes.

The fort at Colchester was

intended to resist the Danes if

ever their threatened

invasion

came, and Norwich Castle was

erected quite as much to

drive back the

Scandinavian

hosts as to keep in order the

citizens. Newcastle and Carlisle

were of

strategic

importance for driving back

the Scots, and Lancaster Keep,

traditionally

said

to have been reared by Roger

de Poitou, but probably of

later date, bore the

brunt

of many a marauding invasion. To

check the incursions of the

Welsh, who

made

frequent and powerful

irruptions into Herefordshire,

many castles were

erected

in Shropshire and Herefordshire,

forming a chain of fortresses which

are

more

numerous than in any other

part of England. They are of

every shape and size,

from

stately piles like Wigmore

and Goodrich, to the smallest

fortified farm, like

Urishay

Castle, a house half mansion, half

fortress. Even the church

towers of

Herefordshire,

with their walls seven or

eight feet thick, such as

that at Ewias

Harold,

look as if they were

designed as strongholds in case of need.

On the

western

and northern borders of England we find

the largest number of

fortresses,

erected

to restrain and keep back troublesome

neighbours.

The

story of the English castles

abounds in interest and romance. Most of

them are

ruins

now, but fancy pictures

them in the days of their

splendour, the abodes

of

chivalry

and knightly deeds, of "fair

ladies and brave men," and each one

can tell

its

story of siege and

battle-cries, of strenuous attack

and gallant defence, of

prominent

parts played in the drama of English

history. To some of these we

shall

presently

refer, but it would need a

very large volume to record

the whole story of

our

English fortresses.

We

have said that the

earliest Norman castle was a motte fortified

by a stockade, an

earthwork

protected with timber

palings. That is the latest

theory amongst

antiquaries,

but there are not a

few who maintain that

the Normans, who

proved

themselves

such admirable builders of

the stoutest of stone churches,

would not

long

content themselves with such

poor fortresses. There were stone

castles before

the

Normans, besides the old

Roman walls at Pevensey,

Colchester, London, and

Lincoln.

And there came from

Normandy a monk named Gundulf in 1070

who was

a

mighty builder. He was consecrated

Bishop of Rochester and began to

build his

cathedral

with wondrous architectural

skill. He is credited with

devising a new style

of

military architecture, and found

much favour with the

Conqueror, who at the

time

especially needed strong

walls to guard himself and

his hungry followers.

He

was

ordered by the King to build

the first beginnings of the

Tower of London. He

probably

designed the keep at

Colchester and the castle of

his cathedral town,

and

set

the fashion of building

these great ramparts of stone which

were so serviceable

in

the subjugation and overawing of

the English. The fashion

grew, much to the

displeasure

of the conquered, who deemed

them "homes of wrong and

badges of

bondage,"

hateful places filled with

devils and evil men who

robbed and spoiled

them.

And when they were ordered

to set to work on castle-building

their impotent

wrath

knew no bounds. It is difficult to

ascertain how many were

constructed

during

the Conqueror's reign.

Domesday tells of forty-nine.

Another authority, Mr.

Pearson,

mentions ninety-nine, and Mrs.

Armitage after a careful

examination of

documents

contends for eighty-six. But

there may have been

many others. In

Stephen's

reign castles spread like an

evil sore over the

land. His traitorous

subjects

broke

their allegiance to their

king and preyed upon the

country. The Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle

records

that "every rich man

built his castles and defended

them against

him,

and they filled the land

full of castles. They greatly oppressed

the wretched

people

by making them work at these

castles, and when the castles

were finished

they

filled them with devils and

evil men. Then they

took those whom they

suspected

to have any goods, by night

and by day, seizing both men

and women,

and

they put them in prison

for their gold and silver,

and tortured them with

pains

unspeakable,

for never were any

martyrs tormented as these

were. They hung

some

up

by their feet and smoked them

with foul smoke; some by

their thumbs or by

the

head,

and they hung burning things

on their feet. They put a

knotted string about

their

heads, and twisted it till it

went into the brain.

They put them into

dungeons

wherein

were adders and snakes and toads, and

thus wore them out.

Some they put

into

a crucet-house, that is,

into a chest that was short and

narrow and not deep,

and

they

put sharp stones in it, and

crushed the man therein so

that they broke all

his

limbs.

There were hateful and grim

things called Sachenteges in

many of the

castles,

and which two or three men

had enough to do to carry. The

Sachentege was

made

thus: it was fastened to a beam, having a

sharp iron to go round a man's

throat

and

neck, so that he might

noways sit, nor lie,

nor sleep, but that he must

bear all

the

iron. Many thousands they

exhausted with hunger. I

cannot, and I may not,

tell

of

all the wounds and all

the tortures that they

inflicted upon the wretched

men of

this

land; and this state of

things lasted the nineteen years

that Stephen was king,

and

ever grew worse and worse.

They were continually

levying an exaction

from

the

towns, which they called

Tenserie,18

and

when the miserable

inhabitants had no

more

to give, then plundered they

and burnt all the towns, so

that well mightest

thou

walk a whole day's journey

nor ever shouldest thou

find a man seated in

a

town

or its lands tilled."

More

than a thousand of these

abodes of infamy are said to

have been built.

Possibly

many of them were timber

structures only. Countless

small towns and

villages

boast of once possessing a fortress.

The name Castle Street remains,

though

the actual site of the

stronghold has long

vanished. Sometimes we find a

mound

which seems to proclaim its

position, but memory is

silent, and the

people

of

England, if the story of the

chronicler be true, have to be

grateful to Henry II,

who

set himself to work to root

up and destroy very many of

these adulterine

castles

which were the abodes of

tyranny and oppression. However,

for the

protection

of his kingdom, he raised

other strongholds, in the

south the grand

fortress

of Dover, which still guards

the straits; in the west,

Berkeley Castle, for

his

friend

Robert FitzHarding, ancestor of Lord

Berkeley, which has remained

in the

same

family until the present

day; in the north, Richmond,

Scarborough, and

Newcastle-upon-Tyne;

and in the east, Orford

Keep. The same stern

Norman keep

remains,

but you can see some

changes in the architecture.

The projection of the

buttresses

is increased, and there is some attempt

at ornamentation. Orford Castle,

which

some guide-books and

directories will insist on confusing

with Oxford

Castle

and stating that it was built by

Robert D'Oiley in 1072, was

erected by

Henry

II to defend the country against

the incursions of the

Flemings and to

safeguard

Orford Haven. Caen stone was

brought for the stone

dressings to

windows

and doors, parapets and groins, but

masses of septaria found on

the shore

and

in the neighbouring marshes

were utilized with such good

effect that the

walls

have

stood the attacks of besiegers and

weathered the storms of the

east coast for

more

than seven centuries. It was built in a

new fashion that was made in

France,

and

to which our English eyes

were unaccustomed, and is somewhat

similar in plan

to

Conisborough Castle, in the valley of

the Don. The plan is

circular with three

projecting

towers, and the keep was

protected by two circular

ditches, one fifteen

feet

and the other thirty feet

distant from its walls.

Between the two ditches

was a

circular

wall with parapet and

battlements. The interior of

the castle was divided

into

three floors; the towers,

exclusive of the turrets, had

five, two of which

were

entresols,

and were ninety-six feet

high, the central keep

being seventy feet.19

The

oven

was at the top of the keep.

The chapel is one of the

most interesting chambers,

with

its original altar still in

position, though much

damaged, and also

piscina,

aumbrey,

and ciborium. This castle

nearly vanished with other

features of

vanishing

England in the middle of the

eighteenth century, Lord

Hereford

proposing

to pull it down for the

sake of the material; but

"it being a necessary

sea-

mark,

especially for ships coming

from Holland, who by

steering so as to make the

castle

cover or hide the church

thereby avoid a dangerous sandbank called

the

Whiting,

Government interfered and prevented

the destruction of the

building."20

In

these keeps the thickness of

the walls enabled them to

contain chambers, stairs,

and

passages. At Guildford there is an

oratory with rude carvings

of sacred

subjects,

including a crucifixion. The

first and second floors were

usually vaulted,

and

the upper ones were of

timber. Fireplaces were built in

most of the rooms,

and

some

sort of domestic comfort was

not altogether forgotten. In

the earlier fortresses

the

walls of the keep enclosed an

inner court, which had rooms

built up to the great

stone

walls, the court afterwards

being vaulted and floors erected. In

order to

protect

the entrance there were

heavy doors with a portcullis, and by

degrees the

outward

defences were strengthened.

There was an outer bailey or

court surrounded

by

a strong wall, with a

barbican guarding the

entrance, consisting of a strong

gate

protected

by two towers. In this lower

or outer court are the

stables, and the mound

where

the lord of the castle

dispenses justice, and where

criminals and traitors

are

executed.

Another strong gateway

flanked by towers protects the

inner bailey, on

the

edge of which stands the

keep, which frowns down upon

us as we enter. An

immense

household was supported in these castles.

Not only were there

men-at-

arms,

but also cooks, bakers, brewers,

tailors, carpenters, smiths, masons, and

all

kinds

of craftsmen; and all this

crowd of workers had to be provided

with

accommodation

by the lord of the castle.

Hence a building in the form

of a large

hall

was erected, sometimes of stone, usually of wood, in

the lower or upper

bailey,

for

these soldiers and artisans, where

they slept and had their

meals.

Amongst

other castles which arose

during this late Norman

and early English

period

of architecture we may mention

Barnard Castle, a mighty stronghold,

held

by

the royal house of Balliol,

the Prince Bishops of

Durham, the Earls of

Warwick,

the

Nevilles, and other powerful

families. Sir Walter Scott

immortalized the Castle

in

Rokeby.

Here is his description of

the fortress:--

High

crowned he sits, in dawning pale,

The

sovereign of the lovely

vale.

What

prospects from the

watch-tower high

Gleam

gradual on the warder's

eye?

Far

sweeping to the east he

sees

Down

his deep woods the course of

Tees,

And

tracks his wanderings by the

steam

Of

summer vapours from the

stream;

And

ere he pace his destined

hour

By

Brackenbury's dungeon

tower,

These

silver mists shall melt

away

And

dew the woods with

glittering spray.

Then

in broad lustre shall be

shown

That

mighty trench of living

stone.

And

each huge trunk that

from the side,

Reclines

him o'er the darksome

tide,

Where

Tees, full many a fathom

low,

Wears

with his rage no common

foe;

Nor

pebbly bank, nor sand-bed

here,

Nor

clay-mound checks his fierce

career,

Condemned

to mine a channelled

way

O'er

solid sheets of marble

grey.

This

lordly pile has seen

the Balliols fighting with

the Scots, of whom John

Balliol

became

king, the fierce contests

between the warlike prelates of

Durham and

Barnard's

lord, the triumph of the

former, who were deprived of

their conquest by

Edward

I, and then its surrender in

later times to the rebels of

Queen Elizabeth.

Another

northern border castle is Norham,

the possession of the Bishop

of Durham,

built

during this period. It was a

mighty fortress, and witnessed

the gorgeous scene

of

the arbitration between the

rival claimants to the

Scottish throne, the

arbiter

being

King Edward I of England,

who forgot not to assert

his own fancied rights

to

the

overlordship of the northern

kingdom. It was, however,

besieged by the Scots,

and

valiant deeds were wrought

before its walls by Sir

William Marmion and

Sir

Thomas

Grey, but the Scots

captured it in 1327 and again in 1513. It is

now but a

battered

ruin. Prudhoe, with its

memories of border wars, and

Castle Rising,

redolent

with the memories of the

last years of the wicked

widow of Edward II,

belong

to this age of castle-architecture, and

also the older portions of

Kenilworth.

Pontefract

Castle, the last fortress

that held out for

King Charles in the Civil

War,

and

in consequence slighted and ruined, can

tell of many dark deeds and

strange

events

in English history. The De

Lacys built it in the early

part of the

thirteenth

century.

Its area was seven acres.

The wall of the castle court

was high and flanked

by

seven towers; a deep moat was

cut on the western side,

where was the

barbican

and

drawbridge. It had terrible dungeons, one

a room twenty-five feet

square,

without

any entrance save a

trap-door in the floor of a

turret. The castle passed,

in

1310,

by marriage to Thomas Earl of

Lancaster, who took part in

the strife between

Edward

II and his nobles, was

captured, and in his own

hall condemned to

death.

The

castle is always associated with

the murder of Richard II,

but contemporary

historians,

Thomas of Walsingham and Gower

the poet, assert that he

starved

himself

to death; others contend

that his starvation was

not voluntary; while

there

are

not wanting those who say

that he escaped to Scotland,

lived there many

years,

and

died in peace in the castle of Stirling,

an honoured guest of Robert III of

Scotland,

in 1419. I have not seen

the entries, but I am told

in the accounts of

the

Chamberlain

of Scotland there are items

for the maintenance of the

King for eleven

years.

But popular tales die hard, and

doubtless you will hear the groans

and see the

ghost

of the wronged Richard some

moonlight night in the

ruined keep of

Pontefract.

He has many companion

ghosts--the Earl of Salisbury,

Richard Duke

of

York, Anthony Wydeville,

Earl Rivers and Grey his

brother, and Sir

Thomas

Vaughan,

whose feet trod the

way to the block, that was

worn hard by many

victims.

The dying days of the old

castle made it illustrious. It was

besieged three

times,

taken and retaken, and saw

amazing scenes of gallantry and

bravery. It held

out

until after the death of the

martyr king; it heard the

proclamation of Charles II,

but

at length was compelled to surrender,

and "the strongest inland

garrison in the

kingdom,"

as Oliver Cromwell termed

it, was slighted and made a

ruin. Its sister

fortress

Knaresborough shared its

fate. Lord Lytton, in

Eugene

Aram, wrote of

it:--

"You

will be at a loss to recognise now the

truth of old Leland's

description

of that once stout and gallant

bulwark of the north,

when

'he

numbrid 11 or 12 Toures in the

walles of the Castel, and one

very

fayre

beside in the second area.'

In that castle the four

knightly

murderers

of the haughty Becket (the

Wolsey of his age) remained

for

a

whole year, defying the

weak justice of the times.

There, too, the

unfortunate

Richard II passed some

portion of his bitter

imprisonment.

And

there, after the battle of

Marston Moor, waved the

banner of the

loyalists

against the soldiers of

Lilburn."

An

interesting story is told of

the siege. A youth, whose

father was in the

garrison,

each

night went into the

deep, dry moat, climbed up

the glacis, and put

provisions

through

a hole where his father

stood ready to receive them. He was

seen at length,

fired

on by the Parliamentary soldiers, and

sentenced to be hanged in sight of

the

besieged

as a warning to others. But a good

lady obtained his respite, and

after the

conquest

of the place was released.

The castle then, once the

residence of Piers

Gaveston,

of Henry III, and of John of

Gaunt, was dismantled and

destroyed.

During

the reign of Henry III great

progress was made in the

improvement and

development

of castle-building. The comfort and

convenience of the dwellers

in

these

fortresses were considered, and if not

very luxurious places they

were made

more

beautiful by art and more desirable as

residences. During the

reigns of the

Edwards

this progress continued, and

a new type of castle was introduced.

The

stern,

massive, and high-towering keep was

abandoned, and the

fortifications

arranged

in a concentric fashion. A fine

hall with kitchens occupied

the centre of

the

fortress; a large number of chambers

were added. The stronghold

itself

consisted

of a large square or oblong

like that at Donnington,

Berkshire, and the

approach

was carefully guarded by strong gateways,

advanced works, walled

galleries,

and barbicans. Deep moats filled with

water increased their

strength and

improved

their beauty.

We

will give some examples of

these Edwardian castles, of which

Leeds Castle,

Kent,

is a fine specimen. It stands on three

islands in a sheet of water

about fifteen

acres

in extent, these islands

being connected in former times by

double

drawbridges.

It consists of two huge piles of

buildings which with a

strong gate-

house

and barbican form four

distinct forts, capable of

separate defence should

any

one

or other fall into the hands

of an enemy. Three causeways, each

with its

drawbridge,

gate, and portcullis, lead to the

smallest island or inner

barbican, a

fortified

mill contributing to the defences. A

stone bridge connects this

island with

the

main island. There stands

the Constable's Tower, and a stone wall

surrounds the

island

and within is the modern

mansion. The Maiden's Tower

and the Water

Tower

defend the island on the

south. A two-storeyed building on

arches now

connects

the main island with

the Tower of the Gloriette,

which has a curious

old

bell

with the Virgin and Child,

St. George and the Dragon, and

the Crucifixion

depicted

on it, and an ancient clock.

The castle withstood a siege in

the time of

Edward

II because Queen Isabella was

refused admission. The King

hung the

Governor,

Thomas de Colepepper, by the

chain of the drawbridge.

Henry IV retired

here

on account of the Plague in London, and

his second wife, Joan of

Navarre, was

imprisoned

here. It was a favourite residence of

the Court in the fourteenth

and

fifteenth

centuries. Here the wife of

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was

tried for

witchcraft.

Dutch prisoners were

confined here in 1666 and contrived to

set fire to

some

of the buildings. It is the

home of the Wykeham Martin

family, and is one of

the

most picturesque castles in

the country.

In

the same neighbourhood is

Allington Castle, an ivy-mantled ruin,

another

example

of vanished glory, only two

tenements occupying the

princely residence of

the

Wyatts, famous in the

history of State and

Letters. Sir Henry, the

father of the

poet,

felt the power of the

Hunchback Richard, and was racked and

imprisoned in

Scotland,

and would have died in the

Tower of London but for a

cat. He rose to

great

honour under Henry VII, and here

entertained the King in great

style. At

Allington

the poet Sir Thomas Wyatt

was born, and spent his days in

writing prose

and

verse, hunting and hawking, and

occasionally dallying after

Mistress Anne

Boleyn

at the neighbouring castle of Hever. He

died here in 1542, and his

son Sir

Thomas

led the insurrection against

Queen Mary and sealed the

fate of himself and

his

race.

Hever

Castle, to which allusion has

been made, is an example of

the transition

between

the old fortress and

the more comfortable mansion

of a country squire or

magnate.

Times were less dangerous,

the country more peaceful

when Sir Geoffrey

Boleyn

transformed and rebuilt the castle

built in the reign of Edward

III by

William

de Hever, but the strong

entrance-gate flanked by towers,

embattled and

machicolated,

and defended by stout doors and three

portcullises and the

surrounding

moat, shows that the

need of defence had not quite

passed away. The

gates

lead into a courtyard around

which the hall, chapel, and

domestic chambers

are

grouped. The long gallery

Anne Boleyn so often

traversed with impatience

still

seems

to re-echo her steps, and

her bedchamber, which used

to contain some of

the

original

furniture, has always a

pathetic interest. The story

of the courtship of

Henry

VIII with "the brown girl

with a perthroat and an

extra finger," as

Margaret

More

described her, is well

known. Her old home,

which was much in decay,

has

passed

into the possession of a

wealthy American gentleman, and

has been recently

greatly

restored and transformed.

Sussex

can boast of many a lordly castle, and in

its day Bodiam must

have been

very

magnificent. Even in its decay

and ruin it is one of the

most beautiful in

England.

It combined the palace of

the feudal lord and

the fortress of a knight.

The

founder,

Sir John Dalyngrudge, was a

gallant soldier in the wars

of Edward III, and

spent

most of his best years in France,

where he had doubtless learned

the art of

making

his house comfortable as well as secure.

He acquired licence to fortify

his

castle

in 1385 "for resistance against our

enemies." There was need of strong

walls,

as

the French often at that

period ravaged the coast of Sussex,

burning towns and

manor-houses.

Clark, the great authority on castles,

says that "Bodiam is

a

complete

and typical castle of the end of the

fourteenth century, laid out

entirely on

a

new site, and constructed after one

design and at one period. It but

seldom

happens

that a great fortress is wholly

original, of one, and that a

known, date, and

so

completely free from

alterations or additions." It is nearly

square, with circular

tower

sixty-five feet high at the

four corners, connected by embattled

curtain-walls,

in

the centre of each of which

square towers rise to an equal

height with the

circular.

The gateway is a large

structure composed of two

flanking towers

defended

by numerous oiletts for

arrows, embattled parapets,

and deep

machicolations.

Over the gateway are

three shields bearing the

arms of Bodiam,

Dalyngrudge,

and Wardieu. A huge portcullis

still frowns down upon

us, and two

others

opposed the way, while above

are openings in the vault

through which

melted

lead, heated sand, pitch, and

other disagreeable things

could be poured on

the

heads of the foe. In the

courtyard on the south

stands the great hall with

its

oriel,

buttery, and kitchen, and amidst

the ruins you can

discern the chapel,

sacristy,

ladies'

bower, presence chamber. The

castle stayed not long in the

family of the

builder,

his son John probably

perishing in the wars, and

passed to Sir Thomas

Lewknor,

who opposed Richard III, and was

therefore attainted of high treason

and

his

castle besieged and taken. It was restored to

him again by Henry VII, but

the

Lewknors

never resided there again.

Waller destroyed it after

the capture of

Arundel,

and since that time it has

been left a prey to the

rains and frosts and

storms,

but manages to preserve much of

its beauty, and to tell

how noble knights

lived

in the days of chivalry.

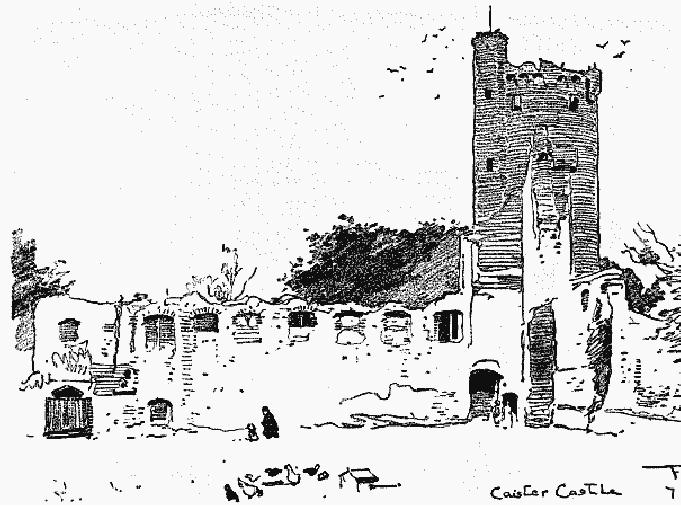

Caister

Castle

Caister

Castle is one of the four principal

castles in Norfolk. It is built of

brick, and

is

one of the earliest edifices in

England constructed of that

material after its

rediscovery

as suitable for building purposes. It

stands with its strong

defences not

far

from the sea on the

barren coast. It was built by Sir

John Fastolfe, who

fought

with

great distinction in the French

wars of Henry V and Henry

VI, and was the

hero

of the Battle of the

Herrings in 1428, when he

defeated the French

and

succeeded

in convoying a load of herrings in

triumph to the English camp

before

Orleans.

It is supposed that he was the

prototype of Shakespeare's Falstaff,

but

beyond

the resemblance in the names

there is little similarity in

the exploits of the

two

"heroes." Sir John Fastolfe,

much to the chagrin of other

friends and relatives,

made

John Paston his heir,

who became a great and prosperous man,

represented

his

county in Parliament, and

was a favourite of Edward IV.

Paston loved Caister,

his

"fair jewell"; but

misfortunes befell him. He had great

losses, and was thrice

confined

in the Fleet Prison and then

outlawed. Those were dangerous

days, and

friends

often quarrelled. Hence

during his troubles the

Duke of Norfolk and

Lord

Scales

tried to get possession of Caister, and

after his death laid siege

to it. The

Pastons

lacked not courage and determination, and

defended it for a year, but

were

then

forced to surrender. However, it was

restored to them, but again forcibly

taken

from

them. However, not by the

sword but by negotiations and

legal efforts, Sir

John

again gained his own, and an embattled

tower at the north-west

corner, one

hundred

feet high, and the north and

west walls remain to tell

the story of this

brave

old

Norfolk family, who by their

Letters

have

done so much to guide us through

the

dark

period to which they

relate.

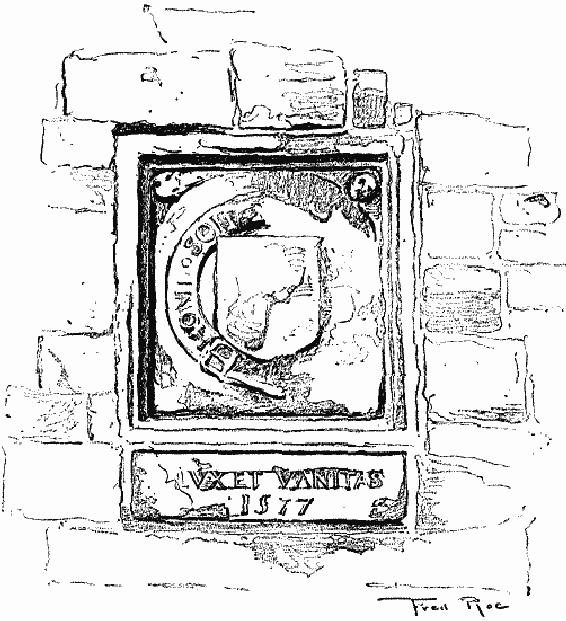

Defaced

Arms. Taunton Castle

We

will journey to the West

Country, a region of castles. The Saxons

were obliged

to

erect their rude earthen

strongholds to keep back the

turbulent Welsh, and

these

were

succeeded by Norman keeps.

Monmouthshire is famous for

its castles. Out of

the

thousand erected in Norman

times twenty-five were built

in that county. There

is

Chepstow Castle with its

Early Norman gateway spanned

by a circular arch

flanked

by round towers. In the

inner court there are

gardens and ruins of a

grand

hall,

and in the outer the remains

of a chapel with evidences of beautifully

groined

vaulting,

and also a winding staircase leading to

the battlements. In the

dungeon of

the

old keep at the south-east

corner of the inner court

Roger de Britolio, Earl

of

Hereford,

was imprisoned for rebellion

against the Conqueror, and in later

times

Henry

Martin, the regicide,

lingered as a prisoner for

thirty years, employing

his

enforced

leisure in writing a book in

order to prove that it is

not right for a man

to

be

governed by one wife. Then

there is Glosmont Castle, the

fortified residence of

the

Earl of Lancaster; Skenfrith Castle,

White Castle, the Album

Castrum of

the

Latin

records, the Landreilo of the

Welsh, with its six

towers, portcullis and

drawbridge

flanked by massive towers, barbican, and

other outworks; and

Raglan

Castle

with its splendid gateway,

its Elizabethan banqueting-hall

ornamented with

rich

stone tracery, its bowling-green, garden

terraces, and spacious courts--an

ideal

place

for knightly tournaments.

Raglan is associated with

the gallant defence of

the

castle

by the Marquis of Worcester in

the Civil War.

Another

famous siege is connected

with the old castle of

Taunton. Taunton was a

noted

place in Saxon days, and the

castle is the earliest English

fortress by some

two

hundred years of which we have

any written historical

record.21

The

Anglo-

Saxon

chronicler states, under the

date 722 A.D.: "This year

Queen Ethelburge

overthrew

Taunton, which Ina had

before built." The buildings

tell their story. We

see

a Norman keep built to the

westward of Ina's earthwork,

probably by Henry de

Blois,

Bishop of Winchester, the

warlike brother of King Stephen.

The gatehouse

with

the curtain ending in drum

towers, of which one only

remains, was first

built

at

the close of the thirteenth

century under Edward I; but

it was restored with

Perpendicular

additions by Bishop Thomas

Langton, whose arms with the

date

1495

may be seen on the

escutcheon above the arch.

Probably Bishop Langton

also

built

the great hall; whilst

Bishop Home, who is sometimes

credited with this

work,

most

likely only repaired the

hall, but tacked on to it the

southward structure on

pilasters,

which shows his arms with

the date 1577. The hall of

the castle was for a

long

period used as Assize

Courts. The castle was purchased by the

Taunton and

Somerset

Arch�ological Society, and is

now most appropriately a

museum.

Taunton

has seen many strange

sights. The town was owned

by the Bishop of

Winchester,

and the castle had its

constable, an office held by

many great men.

When

Lord Daubeney of Barrington

Court was constable in 1497 Taunton

saw

thousands

of gaunt Cornishmen marching on to

London to protest against the

king's

subsidy,

and they aroused the

sympathy of the kind-hearted

Somerset folk, who

fed

them,

and were afterwards fined

for "aiding and comforting"

them. Again, crowds

of

Cornishmen here flocked to the standard

of Perkin Warbeck. The

gallant defence

of

Taunton by Robert Blake,

aided by the townsfolk, against

the whole force of

the

Royalists,

is a matter of history, and also the

rebellion of Monmouth, who

made

Taunton

his head-quarters. This castle,

like every other one in

England, has much

to

tell us of the chief events

in our national

annals.

In

the principality of Wales we

find many noted strong

holds--Conway, Harlech,

and

many others. Carnarvon Castle,

the repair of which is being

undertaken by Sir

John

Puleston, has no rival among

our medieval fortresses for

the grandeur and

extent

of the ruins. It was commenced

about 1283 by Edward I, but

took forty years

to

complete. In 1295 a playful North

Walian, named Madoc, who was

an

illegitimate

son of Prince David, took

the rising stronghold by

surprise upon a fair

day,

massacred the entire

garrison, and hanged the

constable from his own

half-

finished

walls. Sir John Puleston,

the present constable, though he

derives his

patronymic

from the "base, bloody,

and brutal Saxon," is really

a warmly patriotic

Welshman,

and is doing a good work in preserving

the ruins of the fortress

of

which

he is the titular

governor.

We

should like to record the

romantic stories that have

woven themselves

around

each

crumbling keep and bailey-court, to

see them in the days of

their glory when

warders

kept the gate and watching

archers guarded the wall, and the

lord and lady

and

their knights and esquires

dined in the great hall, and

knights practised feats of

arms

in the tilting-ground, and the

banner of the lord waved

over the battlements,

and

everything was ready for

war or sport, hunting or

hawking. But all the

glories

of

most of the castles of

England have vanished, and

naught is to be seen but

ruined

walls

and deserted halls. Some few

have survived and become

royal palaces or

noblemen's

mansions. Such are Windsor,

Warwick, Raby, Alnwick, and

Arundel,

but

the fate of most of them is

very similar. The old

fortress aimed at being

impregnable

in the days of bows and arrows;

but the progress of guns and

artillery

somewhat

changed the ideas with regard to

their security. In the

struggle between

Yorkists

and Lancastrians many a noble

owner lost his castle and

his head. Edward

IV

thinned down castle-ownership, and

many a fine fortress was

left to die. When

the

Spaniards threatened our shores those

who possessed castles tried

to adapt them

for

the use of artillery, and

when the Civil War

began many of them

were

strengthened

and fortified and often made

gallant defences against their

enemies,

such

as Donnington, Colchester, Scarborough,

and Pontefract. When the

Civil War

ended

the last bugle sounded the

signal for their

destruction. Orders were

issued for

their

destruction, lest they

should ever again be thorns in

the sides of the

Parliamentary

army. Sometimes they were

destroyed for revenge, or

because of

their

materials, which were sold

for the benefit of the

Government or for the

satisfaction

of private greed. Lead was torn

from the roofs of chapels

and

banqueting-halls.

The massive walls were so

strong that they resisted to

the last and

had

to be demolished with the

aid of gunpowder. They

became convenient

quarries

for

stone and furnished many a

farm, cottage and manor-house

with materials for

their

construction. Henceforth the

old castle became a ruin. In

its silent marshy

moat

reeds and rushes grow, and ivy covers

its walls, and trees have

sprung up in

the

quiet and deserted courts.

Picnic parties encamp on the green sward,

and

excursionists

amuse themselves in strolling

along the walls and

wonder why they

were

built so thick, and imagine

that the castle was always a

ruin erected for

the

amusement

of the cheap-tripper for

jest and playground. Happily

care is usually

bestowed

upon the relics that

remain, and diligent

antiquaries excavate and try

to

rear

in imagination the stately

buildings. Some have been

fortunate enough to

become

museums, and some modernized

and restored are private residences.

The

English

castle recalls some of the

most eventful scenes in

English history, and

its

bones

and skeleton should be treated with

respect and veneration as an

important

feature

of vanishing

England.

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION