|

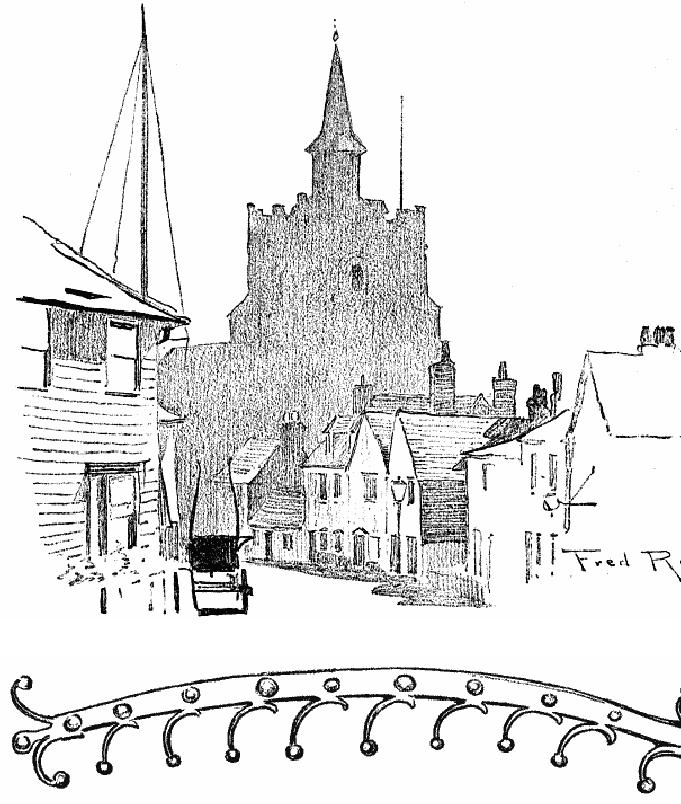

IN STREETS AND LANES |

| << OLD WALLED TOWNS |

| OLD CASTLES >> |

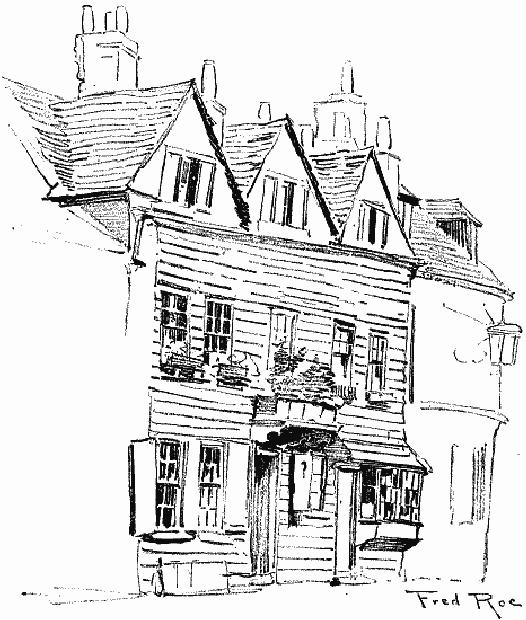

Inscription

in the Mermaid Inn,

Rye

CHAPTER

IV

IN

STREETS AND LANES

I

have said in another place

that no country in the world

can boast of possessing

rural homes

and villages which have half

the charm and picturesqueness of

our

English

cottages and hamlets.10

They

have to be known in order

that they may be

loved.

The hasty visitor may

pass them by and miss half

their attractiveness.

They

have

to be wooed in varying moods in order

that they may display

their charms--

when

the blossoms are bright in

the village orchards, when

the sun shines on the

streams

and pools and gleams on the glories of

old thatch, when autumn

has tinged

the

trees with golden tints, or

when the hoar frost

makes their bare

branches

beautiful

again with new and glistening

foliage. Not even in their

summer garb do

they

look more beautiful. There

is a sense of stability and a wondrous

variety

caused

by the different nature of

the materials used, the

peculiar stone indigenous

in

various districts and the

individuality stamped upon

them by traditional modes

of

building.

We

have still a large number of

examples of the humbler kind

of ancient domestic

architecture,

but every year sees

the destruction of several of

these old buildings,

which

a little care and judicious

restoration might have saved.

Ruskin's words

should

be writ in bold, big letters

at the head of the by-laws

of every district

council.

"Watch

an old building with anxious

care; guard it as best you

may,

and

at any cost, from any

influence of dilapidation. Count

its stones as

you

would the jewels of a crown.

Set watchers about it, as if

at the gate

of

a besieged city; bind it

together with iron when it

loosens; stay it

with

timber when it declines. Do

not care about the

unsightliness of the

aid--better

a crutch than a lost limb;

and do this tenderly

and

reverently

and continually, and many a generation

will still be born and

pass

away beneath its

shadow."

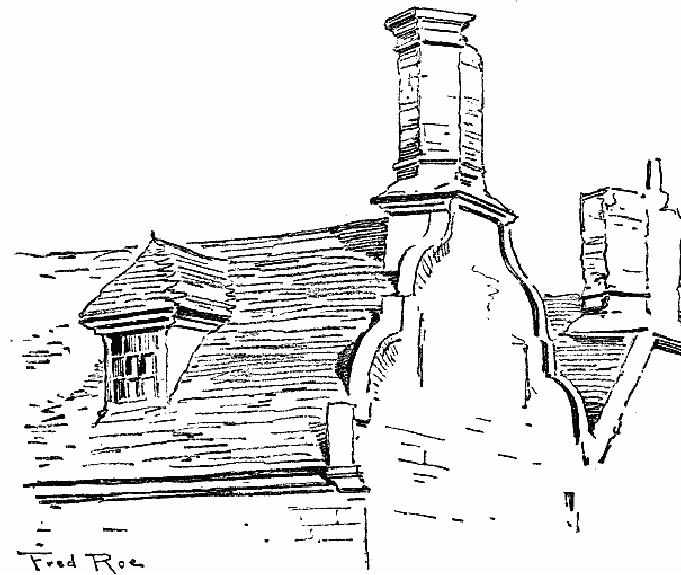

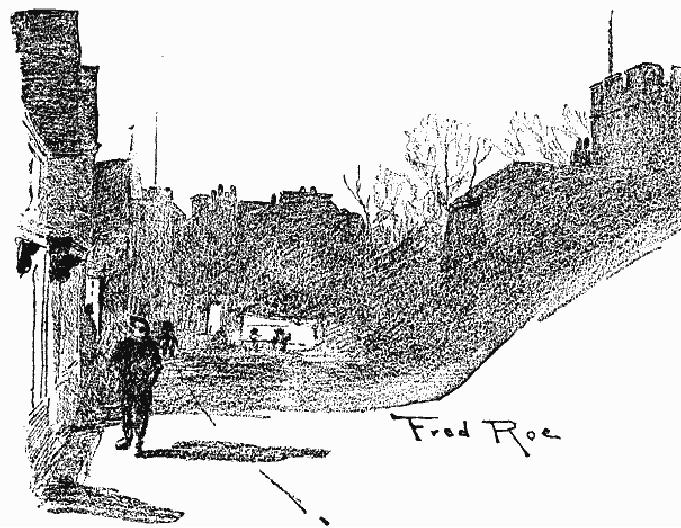

Relic

of Lynn Siege in Hampton Court,

King's Lynn

Hampton

Court, King's Lynn,

Norfolk

If

this sound advice had been

universally taken many a

beautiful old cottage

would

have

been spared to us, and our

eyes would not be offended

by the wondrous

creations

of the estate agents and

local builders, who have no

other ambition but to

build

cheaply. The contrast

between the new and the

old is indeed deplorable.

The

old

cottage is a thing of beauty. Its

odd, irregular form and

various harmonious

colouring,

the effects of weather,

time, and accident, environed

with smiling

verdure

and sweet old-fashioned garden flowers,

its thatched roof, high

gabled

front,

inviting porch overgrown

with creepers, and casement

windows, all combine

to

form a fair and beautiful

home. And then look at

the modern cottage with

its

glaring

brick walls, slate roof,

ungainly stunted chimney, and

note the difference.

Usually

these modern cottages are

built in a row, each one

exactly like its

fellow,

with

door and window frames

exactly alike, brought over

ready-made from

Norway

or

Sweden. The walls are thin,

and the winds of winter blow

through them

piteously,

and if a man and his wife

should unfortunately "have

words" (the

pleasing

country euphemism for a

violent quarrel) all their

neighbours can hear

them.

The scenery is utterly

spoilt by these ugly

eyesores. Villas at Hindhead

seem

to

have broken out upon

the once majestic hill like

a red skin eruption. The

jerry-

built

villa is invading our heaths and

pine-woods; every street in our

towns is

undergoing

improvement; we are covering

whole counties with houses.

In

Lancashire

no sooner does one village end its mean

streets than another

begins.

London

is ever enlarging itself,

extending its great maw over

all the country

round.

The

Rev. Canon Erskine Clarke,

Vicar of Battersea, when he first

came to reside

near

Clapham Junction, remembers the green

fields and quiet lanes with

trees on

each

side that are now

built over. The street

leading from the station

lined with

shops

forty years ago had hedges and

trees on each side. There

were great houses

situated

in beautiful gardens and parks

wherein resided some of the

great City

merchants,

county families, the leaders

in old days of the influential

"Clapham

sect."

These gardens and parks have been

covered with streets and

rows of cottages

and

villas; some of the great

houses have been pulled

down and others turned

into

schools

or hospitals, valued only at

the rent of the land on

which they stand. All

this

is

inevitable. You cannot stop all

this any more than

Mrs. Partington could stem

the

Atlantic

tide with a housemaid's mop.

But ere the flood

has quite swallowed up

all

that

remains of England's natural and

architectural beauties, it may be useful

to

glance

at some of the buildings

that remain in town and

country ere they have

quite

vanished.

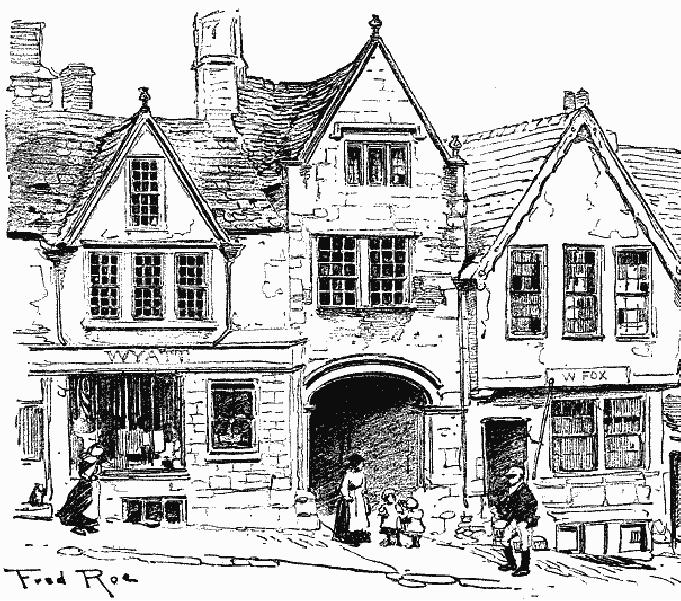

Mill

Street, Warwick

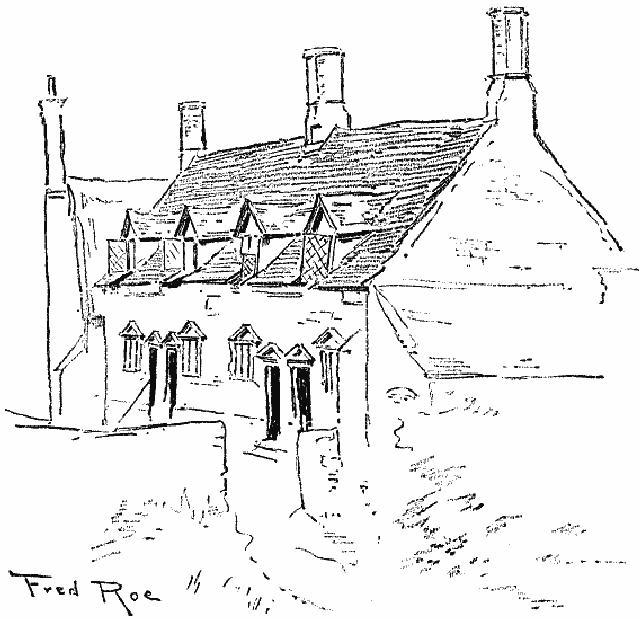

Beneath

the shade of the lordly

castle of Warwick, which has

played such an

important

part in the history of

England, the town of Warwick

sprang into

existence,

seeking protection in lawless times

from its strong walls and

powerful

garrison.

Through its streets often

rode in state the proud

rulers of the castle

with

their

men-at-arms--the Beauchamps, the

Nevilles, including the great

"King-

maker,"

Richard Neville, the

Dudleys, and the Grevilles.

They contributed to

the

building

of their noble castle, protected

the town, and were borne to

their last

resting-place

in the fine church, where

their tombs remain. The

town has many

relics

of its lords, and possesses

many half-timbered graceful houses. Mill

Street is

one

of the most picturesque

groups of old-time dwellings, a

picture that lingers

in

our

minds long after we have

left the town and fortress

of the grim old Earls

of

Warwick.

Oxford

is a unique city. There is no place

like it in the world.

Scholars of

Cambridge,

of course, will tell me that I am wrong,

and that the town on the Cam

is

a

far superior place, and then

point triumphantly to "the

backs." Yes, they are

very

beautiful,

but as a loyal son of Oxford

I may be allowed to prefer

that stately city

with

its towers and spires, its

wealth of college buildings,

its exquisite

architecture

unrivalled

in the world. Nor is the

new unworthy of the old.

The buildings at

Magdalen,

at Brazenose, and even the New

Schools harmonize not

unseemly with

the

ancient structures. Happily

Keble is far removed from

the heart of the city,

so

that

that somewhat unsatisfactory,

unsuccessful pile of brickwork

interferes not

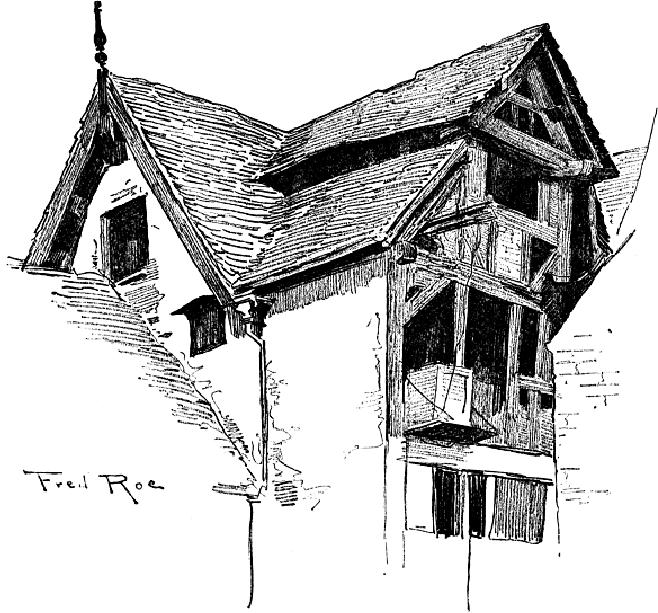

with

its joy. In the streets and

lanes of modern Oxford we can search

for and

discover

many types of old-fashioned,

humble specimens of domestic

art, and we

give

as an illustration some houses

which date back to Tudor

times, but have,

alas!

been

recently demolished.

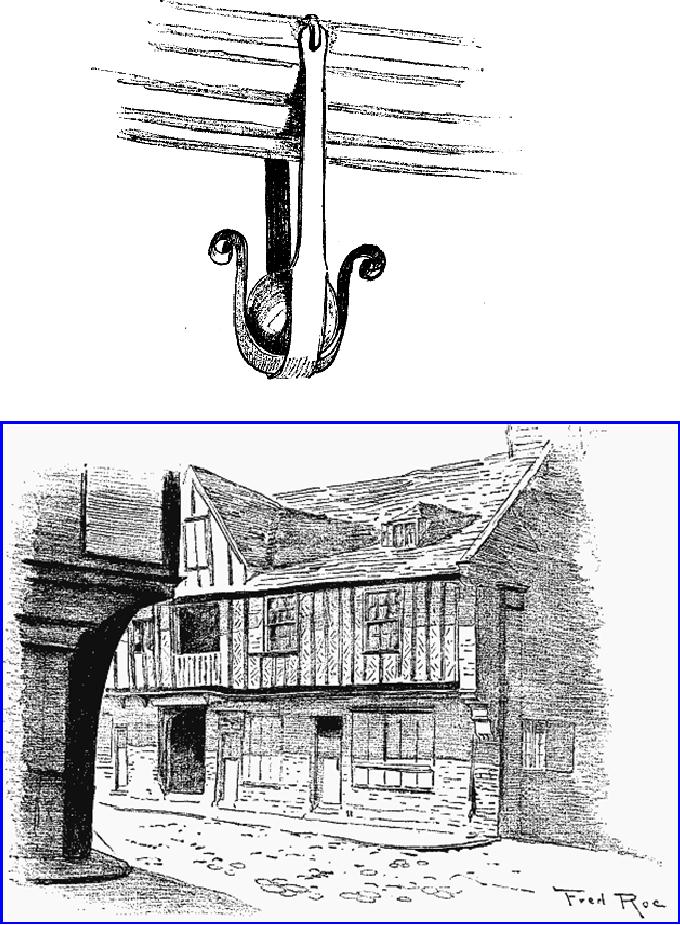

Tudor

Tenements, New Inn Hall St,

Oxford. Now

demolished.

Many

conjectures have been made

as to the reason why our

forefathers preferred to

rear

their houses with the

upper storeys projecting out

into the streets. We can

understand

that in towns where space

was limited it would be an advantage

to

increase

the size of the upper rooms,

if one did not object to the

lack of air in the

narrow

street and the absence of sunlight.

But we find these same

projecting storeys

in

the depth of the country,

where there could have

been no restriction as to

the

ground

to be occupied by the house.

Possibly the fashion was

first established of

necessity

in towns, and the

traditional mode of building was

continued in the

country.

Some say that by this means

our ancestors tried to

protect the lower part

of

the

house, the foundations, from

the influence of the

weather; others with

some

ingenuity

suggest that these

projecting storeys were

intended to form a

covered

walk

for passengers in the streets, and to

protect them from the

showers of slops

which

the careless housewife of

Elizabethan times cast

recklessly from the

upstairs

windows.

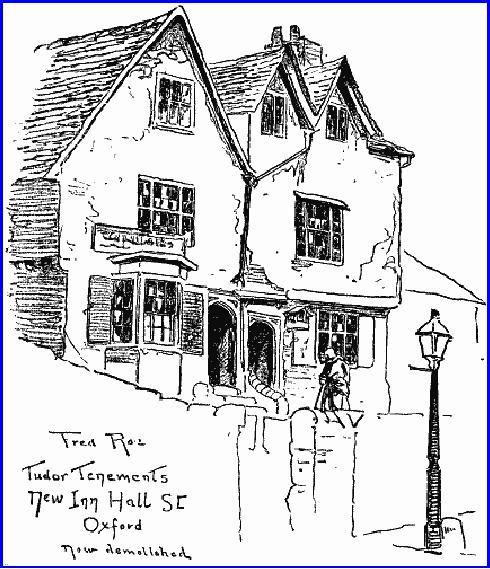

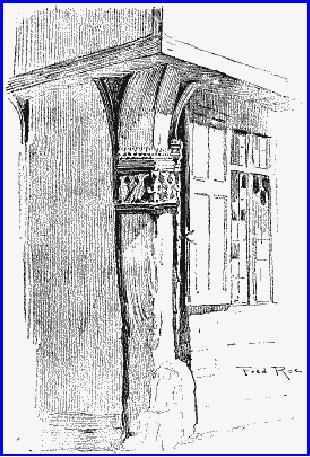

Architects tell us that it was

purely a matter of construction.

Our

forefathers

used to place four strong

corner-posts, framed from

the trunks of oak

trees,

firmly sunk into the

ground with their roots

left on and placed upward,

the

roots

curving outwards so as to form

supports for the upper

storeys. These curved

parts,

and often the posts also,

were often elaborately

carved and ornamented, as in

the

example which our artist

gives us of a corner-post of a house in

Ipswich.

In

The

Charm of the English Village

I

have tried to describe the

methods of the

construction

of these timber-framed houses,11

and it is

perhaps unnecessary for me

to

repeat what is there recorded. In

fact, there were three

types of these

dwelling-

places,

to which have been given

the names Post and Pan,

Transom Framed, and

Intertie

Work. In judging of the age

of a house it will be remembered that

the

nearer

together the upright posts

are placed the older the

house is. The builders

as

time

went on obtained greater confidence,

set their posts wider

apart, and held

them

together

by transoms.

Gothic

Corner-post. The Half Moon

Inn, Ipswich

Surrey

is a county of good cottages and

farm-houses, and these have had

their

chroniclers

in Miss Gertrude Jekyll's

delightful Old

West Surrey and in the

more

technical

work of Mr. Ralph Nevill,

F.S.A. The numerous works on

cottage and

farm-house

building published by Mr. Batsford

illustrate the variety of

styles that

prevailed

in different counties, and which

are mainly attributable to

the variety in

the

local materials in the

counties. Thus in the

Cotswolds, Northamptonshire,

Derbyshire,

Yorkshire, Westmorland, Somersetshire, and

elsewhere there is good

building-stone;

and there we find charming

examples of stone-built cottages

and

farm-houses,

altogether satisfying. In several

counties where there is

little stone and

large

forests of timber we find

the timber-framed dwelling

flourishing in all

its

native

beauty. In Surrey there are

several materials for

building, hence there is a

charming

diversity of domiciles. Even

the same building sometimes

shows walls of

stone

and brick, half-timber and plaster,

half-timber and tile-hanging,

half-timber

with

panels filled with red brick,

and roofs of thatch or

tiles, or stone slates

which

the

Horsham quarries

supplied.

Timber-built

House, Shrewsbury

These

Surrey cottages have changed

with age. Originally they

were built with

timber

frames, the panels being

filled in with wattle and

daub, but the storms

of

many

winters have had their

effect upon the structure.

Rain drove through

the

walls,

especially when the ends of

the wattle rotted a little,

and draughts were

strong

enough to blow out the

rushlights and to make the house

very

uncomfortable.

Oak timbers often shrink.

Hence the joints came

apart, and being

exposed

to the weather became decayed. In

consequence of this the

buildings

settled,

and new methods had to be

devised to make them weather-proof.

The

villages

therefore adopted two or

three means in order to

attain this end.

They

plastered

the whole surface of the

walls on the outside, or

they hung them with

deal

boarding

or covered them with tiles.

In Surrey tile-hung houses

are more common

than

in any other part of the

country. This use of

weather-tiles is not very

ancient,

probably

not earlier than 1750, and

much of this work was done

in that century or

early

in the nineteenth. Many of

these tile-hung houses are

the old sixteenth-

century

timber-framed structures in a new

shell. Weather-tiles are

generally flatter

and

thinner than those used for

roofing, and when bedded in

mortar make a

thoroughly

weather-proof wall. Sometimes they

are nailed to boarding, but

the

former

plan makes the work

more durable, though the

courses are not so

regular.

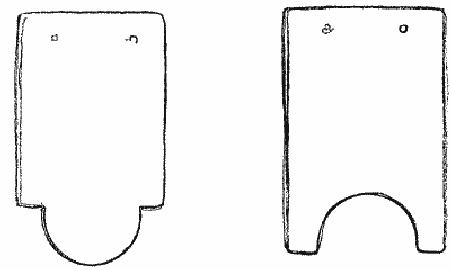

These

tiles have various shapes,

of which the commonest is

semicircular,

resembling

a fish-scale. The same form

with a small square shoulder

is very

generally

used, but there is a great

variety, and sometimes those with

ornamental

ends

are blended with plain ones.

Age imparts a very beautiful

colour to old tiles,

and

when covered with lichen

they assume a charming

appearance which

artists

love

to depict.

The

mortar used in these old

buildings is very strong and

good. In order to

strengthen

the mortar used in Sussex

and Surrey houses and

elsewhere, the

process

of

"galleting" or "garreting" was adopted.

The brick-layers used to

decorate the

rather

wide and uneven mortar joint

with small pieces of black

ironstone stuck into

the

mortar. Sussex was once

famous for its ironwork, and

ironstone is found in

plenty

near the surface of the

ground in this district.

"Galleting" dates back to

Jacobean

times, and is not to be found in

sixteenth-century work.

Sussex

houses are usually

whitewashed and have thatched

roofs, except when

Horsham

slates or tiles are used.

Thatch as a roofing material will soon

have

altogether

vanished with other features

of vanishing England. District

councils in

their

by-laws usually insert

regulations prohibiting thatch to be

used for roofing.

This

is one of the mysteries of the

legislation of district councils.

Rules, suitable

enough

for towns, are applied to

the country villages, where

they are altogether

unsuitable

or unnecessary. The danger of fire

makes it inadvisable to have

thatched

roofs

in towns, or even in some

villages where the houses

are close together,

but

that

does not apply to isolated

cottages in the country. The

district councils do

not

compel

the removal of thatch, but

prohibit new cottages from

being roofed with

that

material. There is, however,

another cause for the

disappearance of thatched

roofs,

which form such a beautiful

feature in the English landscape. Since

mowing-

machines

came into general use in

the harvest fields the

straw is so bruised that it

is

not

fit for thatching, at least it is

not so suitable as the straw

which was cut by the

hand.

Thatching, too, is almost a

lost art in the country.

Indeed ricks have to

be

covered

with thatch, but "the

work for this temporary

purpose cannot compare with

that

of the old roof-thatcher,

with his 'strood' or 'frail'

to hold the loose straw,

and

his

spars--split hazel rods pointed at

each end--that with a

dexterous twist in

the

middle

make neat pegs for the

fastening of the straw rope

that he cleverly

twists

with

a simple implement called a

'wimble.' The lowest course

was finished with an

ornamental

bordering of rods with a diagonal

criss-cross pattern between, all

neatly

pegged

and held down by the

spars."12

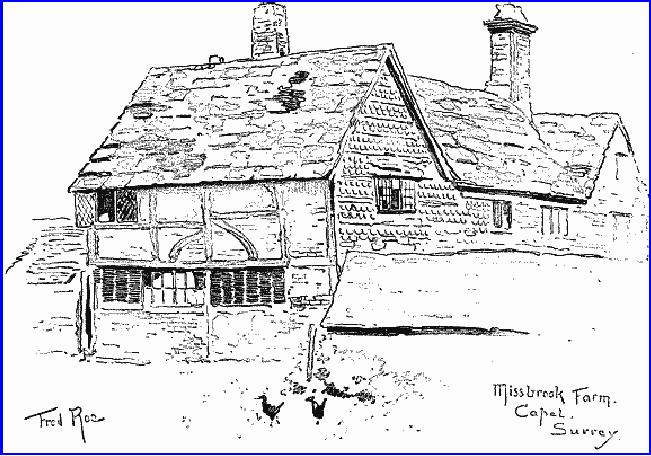

Missbrook

Farm. Capel. Surrey.

Horsham

stone makes splendid roofing

material. This stone easily

flakes into plates

like

thick slates, and forms large

grey flat slabs on which

"the weather works like

a

great

artist in harmonies of moss

lichen and stain. No roofing so

combines dignity

and

homeliness, and no roofing, except

possibly thatch (which,

however, is short-

lived),

so surely passes into the

landscape."13

It is to be regretted

that this stone is

no

longer used for

roofing--another feature of vanishing

England. The stone is

somewhat

thick and heavy, and modern

rafters are not adapted to

bear their weight.

If

you want to have a roof of

Horsham stone, you can only

accomplish your

purpose

by pulling down an old cottage and

carrying off the slabs.

Perhaps the

small

Cotswold stone slabs are

even more beautiful. Old

Lancashire and

Yorkshire

cottages

have heavy stone roofs which

somewhat resemble those fashioned

with

Horsham

slabs.

The

builders and masons of our

country cottages were

cunning men, and

adapted

their

designs to their materials. You will

have noticed that the

pitch of the Horsham

-slated

roof is unusually flat. They

observed that when the sides

of the roof were

deeply

sloping, as in the case of

thatched roofs, the heavy

stone slates strained and

dragged

at the pegs and laths and

fell and injured the

roof. Hence they

determined

to

make the slope less steep.

Unfortunately the rain did

not then easily run

off, and

in

order to prevent the water

penetrating into the house

they were obliged to

adopt

additional

precautions. Therefore they cemented

their roofs and stopped them

with

mortar.

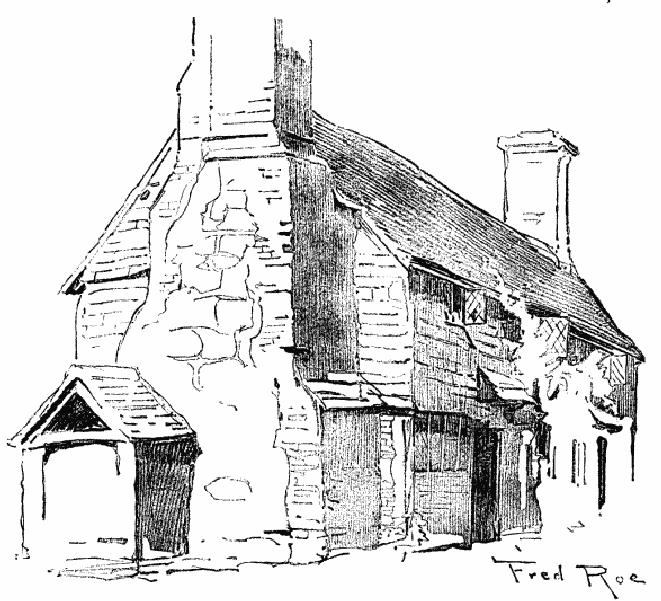

Cottage

at Capel, Surrey

Very

lovely are these South

Country cottages, peaceful, picturesque,

pleasant, with

their

graceful gables and jutting

eaves, altogether delightful.

Well sang a loyal

Sussex

poet:--

If

I ever become a rich

man,

Or

if ever I grow to be

old,

I

will build a house with deep

thatch14

To

shelter me from the

cold;

And

there shall the Sussex

songs be sung

And

the story of Sussex

told.

We

give some good examples of

Surrey cottages at the

village of Capel in the

neighbourhood

of Dorking, a charming region

for the study of

cottage-building.

There

you can see some charming

ingle-nooks in the interior of

the dwellings, and

some

grand farm-houses. Attached to

the ingle-nook is the oven,

wherein bread is

baked

in the old-fashioned way, and

the chimneys are large and

carried up above

the

floor of the first storey,

so as to form space for

curing bacon.

Farm-house,

Horsmonden, Kent

Horsmonden,

Kent, near Lamberhurst, is beautifully

situated among

well-wooded

scenery,

and the farm-house shown in

the illustration is a good example of

the

pleasant

dwellings to be found

therein.

East

Anglia has no good building-stone, and

brick and flint are the

principal

materials

used in that region. The

houses built of the dark,

dull, thin old bricks,

not

of

the great staring modern

varieties, are very

charming, especially when

they are

seen

against a background of wooded hills. We

give an illustration of some

cottages

at

Stow Langtoft,

Suffolk.

Seventeenth-century

Cottages, Stow Langtoft,

Suffolk

The

old town of Banbury, celebrated

for its cakes, its Cross,

and its fine lady

who

rode

on a white horse accompanied by the sound

of bells, has some excellent

"black

and

white" houses with pointed

gables and enriched barge-boards pierced in

every

variety

of patterns, their finials

and pendants, and pargeted fronts,

which give an air

of

picturesqueness contrasting strangely

with the stiffness of the

modern brick

buildings.

In one of these is established the old

Banbury Cake Shop. In the

High

Street

there is a very perfect

example of these Elizabethan houses,

erected about the

year

1600. It has a fine oak

staircase, the newels

beautifully carved and

enriched

with

pierced finials and pendants. The

market-place has two good

specimens of the

same

date, one of which is probably

the front of the Unicorn

Inn, and had a fine

pair

of wooden gates bearing the

date 1684, but I am not sure

whether they are

still

there.

The Reindeer Inn is one of the chief

architectural attractions of the

town. We

see

the dates 1624 and 1637 inscribed on

different parts of the building,

but its

chief

glory is the Globe Room,

with a large window, rich

plaster ceiling, good

panelling,

elaborately decorated doorways and

chimney-piece. The courtyard is

a

fine

specimen of sixteenth-century architecture. A

curious feature is the

mounting-

block

near the large oriel window.

It must have been designed

not for mounting

horses,

unless these were of giant

size, but for climbing to

the top of coaches.

The

Globe

Room is a typical example of

Vanishing England, as it is reported

that the

whole

building has been sold

for transportation to America. We

give an illustration

of

some old houses in Paradise

Square, that does not belie

its name. The houses

all

round

the square are thatched, and

the gardens in the centre

are a blaze of

colour,

full

of old-fashioned flowers. The

King's Head Inn has a good courtyard.

Banbury

suffered

from a disastrous fire in 1628 which

destroyed a great part of the

town,

and

called forth a vehement

sermon from the Rev.

William Whateley, of two

hours'

duration,

on the depravity of the

town, which merited such a

severe judgment. In

spite

of the fire much old

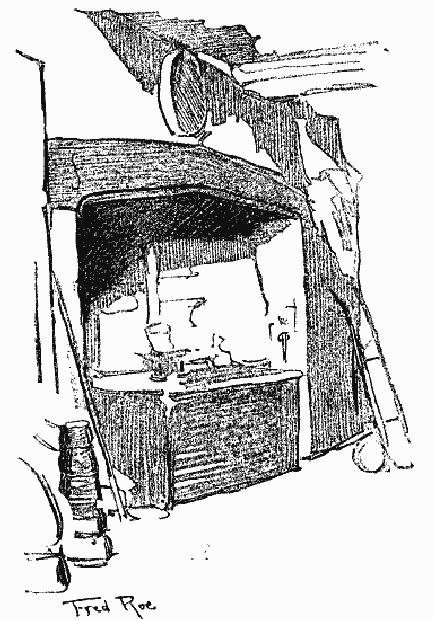

work survived, and we give an

illustration of a Tudor

fire

-place

which you cannot now

discover, as it is walled up into

the passage of an

ironmonger's

shop.

The

"Fish House," Littleport,

Cambs

The

old ports and harbours are

always attractive. The old

fishermen mending

their

nets

delight to tell their stories of

their adventures, and retain

their old customs and

usages,

which are profoundly

interesting to the lovers of

folk-lore. Their houses

are

often

primitive and quaint. There is

the curious Fish House at

Littleport,

Cambridgeshire,

with part of it built of

stone, having a gable and Tudor

weather-

moulding

over the windows. The rest

of the building was added at

a later date.

Sixteenth-century

Cottage, formerly standing in Upper

Deal, Kent

In

Upper Deal there is an

interesting house which shows

Flemish influence in

the

construction

of its picturesque gable and

octagonal chimney, and contrasted with

it

an

early sixteenth-century cottage much

the worse for

wear.

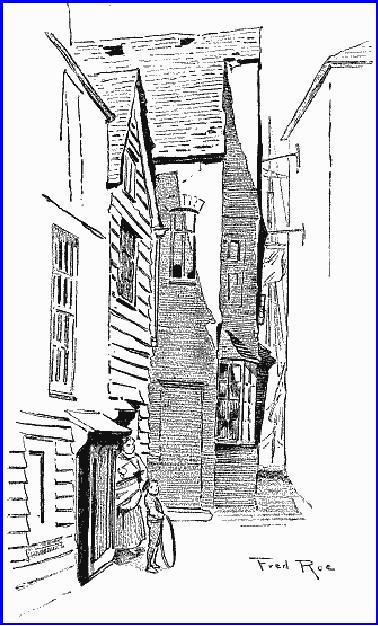

We

give a sketch of a Portsmouth

row which resembles in

narrowness those at

Yarmouth,

and in Crown Street there is a battered,

three-gabled, weather-boarded

house

which has evidently seen

better days. There is a fine

canopy over the

front

door

of Buckingham House, wherein George

Villiers, Duke of Buckingham,

was

assassinated

by John Felton on August

23rd, 1628.

Gable,

Upper Deal, Kent

The

Vale of Aylesbury is one of the

sweetest and most charmingly

characteristic

tracts

of land in the whole of

rural England, abounding

with old houses. The

whole

countryside

literally teems with

picturesque evidences of the past

life and history of

England.

Ancient landmarks and associations are so

numerous that it is difficult

to

mention

a few without seeming to ignore

unfairly their equally

interesting

neighbours.

Let us take the London road,

which enters the shire from

Middlesex

and

makes for Aylesbury, a

meandering road with patches of

scenery strongly

suggestive

of Birket Foster's landscapes.

Down a turning at the foot

of the lovely

Chiltern

Hills lies the secluded

village of Chalfont St.

Giles. Here Milton, the

poet,

sought

refuge from plague-stricken

London among a colony of

fellow Quakers, and

here

remains, in a very perfect state,

the cottage in which he lived and

was visited

by

Andrew Marvel. It is said

that his neighbour Elwood,

one of the Quaker

fraternity,

suggested the idea of

"Paradise Regained," and

that the draft of the

latter

poem

was written upon a great oak

table which may be seen in

one of the low-

pitched

rooms on the ground floor. I

fancy that Milton must

have beautified and

repaired

the cottage at the period of

his tenancy. The mantelpiece

with its classic

ogee

moulding belongs certainly to

his day, and some other

minor details may

also

be

noticed which support this

inference. It is not difficult to

imagine that one who

was

accustomed to metropolitan comforts would

be dissatisfied with the open

hearth

common to country cottages of

that poet's time, and have

it enclosed in the

manner

in which we now see it.

Outside the garden is brilliant

with old-fashioned

flowers,

such as the poet loved. A stone

scutcheon may be seen peeping

through the

shrubbery

which covers the front of

the cottage, but the arms

which it displays are

those

of the Fleetwoods, one time

owners of these tenements.

Between the years

1709

and 1807 the house was used as an inn.

Milton's cottage is one of our

national

treasures,

which (though not actually

belonging to the nation) has

successfully

resisted

purchase by our American cousins and

transportation across the

Atlantic.

A

Portsmouth "Row"

The

entrance to the churchyard in

Chalfont St. Giles is

through a wonderfully

picturesque

turnstile or lich-gate under an

ancient house in the High

Street. The

gate

formerly closed itself mechanically by

means of a pulley to which

was

attached

a heavy weight. Unfortunately

this weight was not boxed

in--as in the

somewhat

similar example at Hayes, in

Middlesex--and an accident

which

happened

to some children resulted in

its removal.

Lich-gate,

Chalfont St. Giles,

Bucks

A

good many picturesque old

houses remain in the

village, among them being

one

called

Stonewall Farm, a structure of

the fifteenth century with

an original billet-

moulded

porch and Gothic barge-boards.

There

is a certain similarity about

the villages that dot

the Vale of Aylesbury.

The

old

Market House is usually a

feature of the High

Street--where it has not

been

spoilt

as at Wendover. Groups of picturesque

timber cottages, thickest round

the

church,

and shouldered here and there by

their more respectable and

severe

Georgian

brethren, are common to all,

and vary but little in their

general aspect and

colouring.

Memories and legends haunt every

hamlet, the very names of

which

have

an ancient sound carrying us

vaguely back to former days.

Prince's

Risborough,

once a manor of the Black

Prince; Wendover, the

birthplace of Roger

of

Wendover, the medieval

historian, and author of the

Chronicle Flores

Historiarum,

or History of the World from the

Creation to the year 1235, in

modern

language a somewhat "large

order"; Hampden, identified to

all time with

the

patriot of that name; and so

on indefinitely. At Monk's Risborough,

another

hamlet

with an ancient-sounding name, but

possessing no special history, is

a

church

of the Perpendicular period

containing some features of exceptional

interest,

and

internally one of the most

charmingly picturesque of its

kind. The carved

tie-

beams

of the porch with their

masks and tracery and the great stone

stoup which

appears

in one corner have an unrestored

appearance

which is quite delightful

in

these

days of over-restoration. The massive oak

door has some curious

iron fittings,

and

the interior of the church

itself displays such

treasures as a magnificent

early

Tudor

roof and an elegant fifteenth-century

chancel-screen, on the latter of

which

some

remains of ancient painting

exist.15

Fifteenth-century

Handle on Church Door,

Monk's Risborough,

Bucks

Thame,

just across the Oxfordshire

border, is another town of

the greatest

interest.

The

noble parish church here

contains a number of fine

brasses and tombs,

including

the recumbent effigies of

Lord John Williams of Thame

and his wife,

who

flourished in the reign of

Queen Mary. The

chancel-screen is of uncommon

character,

the base being richly

decorated with linen panelling,

while above rises an

arcade

in which Gothic form mingles

freely with the

grotesqueness of the

Renaissance.

The choir-stalls are also

lavishly ornamented with the

linen-fold

decoration.

The

centre of Thame's broad High Street is

narrowed by an island of houses,

once

termed

Middle Row, and above the

jumble of tiled roofs here

rises like a watch-

tower

a most curious and interesting

medieval house known as the

"Bird Cage Inn."

About

this structure little is

known; it is, however,

referred to in an old document

as

the

"tenement called the Cage,

demised to James Rosse by

indenture for the term

of

100

years, yielding therefor by

the year 8s.," and appears

to have been a farm-

house.

The document in question is a

grant of Edward IV to Sir

John William of the

Charity

or Guild of St. Christopher in

Thame, founded by Richard

Quartemayne,

Squier,

who died in the year 1460.

This house, though in some

respects adapted

during

later years from its

original plan, is structurally

but little altered, and

should

be

taken in hand and intelligently

restored

as an object of local attraction

and

interest.

The choicest oaks of a small

forest must have supplied

its framework,

which

stands firm as the day

when it was built. The fine

corner-posts (now

enclosed)

should be exposed to view, and

the mullioned windows which

jut out

over

a narrow passage should be

opened up. If this could be

done--and not

overdone--the

"Bird Cage" would hardly be

surpassed as a miniature specimen

of

medieval

timber architecture in the

county. A stone doorway of Gothic

form and a

kind

of almery or safe exist in

its cellars.

A

school was founded at Thame

by Lord John Williams, whose

recumbent effigy

exists

in the church, and amongst

the students there during

the second quarter of

the

seventeenth

century was Anthony Wood,

the Oxford antiquary. Thame

about this

time

was the centre of military

operations between the

King's forces and the

rebels,

and

was continually being beaten up by one

side or the other. Wood,

though but a

boy

at the time, has left on

record in his narrative some

vivid impressions of

the

conflicts

which he personally witnessed, and

which bring the disjointed

times

before

us in a vision of strange and absolute

reality.

He

tells of Colonel Blagge, the

Governor of Wallingford Castle, who

was on a

marauding

expedition, being chased

through the streets of Thame

by Colonel

Crafford,

who commanded the

Parliamentary garrison at Aylesbury, and

how one

man

fell from his horse, and the

Colonel "held a pistol to

him, but the trooper

cried

'Quarter!'

and the rebels came up and rifled

him and took him and his

horse away

with

them." On another occasion, just as a

company of Roundhead soldiers

were

sitting

down to dinner, a Cavalier

force appeared "to beat up

their quarters," and

the

Roundheads

retired in a hurry, leaving

"A.W. and the schoolboyes,

sojourners in

the

house," to enjoy their

venison pasties.

He

tells also of certain doings at

the Nag's Head, a house that still

exists--a very

ancient

hostelry, though not nearly

so old a building as the

Bird Cage Inn. The

sign

is

no longer there, but some

interesting features remain,

among them the huge

strap

hinges

on the outer door, fashioned

at their extremities in the

form of fleurs-de-lis.

We

should like to linger long

at Thame and describe the

wonders at Thame

Park,

with

its remains of a Cistercian abbey

and the fine Tudor

buildings of Robert

King,

last

abbot and afterward the

first Bishop of Oxford. The

three fine oriel

windows

and

stair-turret, the noble

Gothic dining-hall and abbot's

parlour panelled with

oak

in

the style of the linen

pattern, are some of the

finest Tudor work in the

country.

The

Prebendal house and chapel built by

Grosset�te are also worthy of

the closest

attention.

The chapel is an architectural gem of

Early English design, and

the rest of

the

house with its later

Perpendicular windows is admirable.

Not far away is

the

interesting

village of Long Crendon, once a

market-town, with its fine

church and

its

many picturesque houses, including Staple

Hall, near the church, with

its noble

hall,

used for more than

five centuries as a manorial

court-house on behalf of

various

lords of the manor,

including Queen Katherine,

widow of Henry V. It

has

now

fortunately passed into the

care of the National Trust,

and its future is

secured

for

the benefit of the nation.

The house is a beautiful half-timbered

structure, and

was

in a terribly dilapidated condition. It

is interesting both historically

and

architecturally,

and is note-worthy as illustrating the

continuity of English life,

that

the

three owners from whom

the Trust received the

building, Lady Kinloss,

All

Souls'

College, and the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners, are

the successors in title

of

three

daughters of an Earl of Pembroke in the

thirteenth century. It is fortunate

that

the

old house has fallen into

such good hands. The village

has a Tudor manor-

house

which has been

restored.

Another

court-house, that at Udimore, in Sussex,

near Rye, has, we believe,

been

saved

by the Trust, though the

owner has retained

possession. It is a picturesque

half-timbered

building of two storeys with

modern wings projecting at

right angles

at

each end. The older

portion is all that remains

of a larger house which appears

to

have

been built in the fifteenth

century. The manor belonged

to the Crown, and it

is

said

that both Edward I and

Edward III visited it. The

building was in a

very

dilapidated

condition, and the owner

intended to destroy it and replace it

with

modern

cottages. We hope that this scheme

has now been abandoned, and

that the

old

house is safe for many years to

come.

Weather-boarded

Houses, Crown Street,

Portsmouth

At

the other end of the county

of Oxfordshire remote from

Thame is the

beautiful

little

town of Burford, the gem of

the Cotswolds. No wonder

that my friend

"Sylvanus

Urban," otherwise Canon

Beeching, sings of its

charm:--

Oh

fair is Moreton in the

marsh

And

Stow on the wide

wold,

Yet

fairer far is Burford

town

With

its stone roofs grey and

old;

And

whether the sky be hot and

high,

Or

rain fall thin and

chill,

The

grey old town on the

lonely down

Is

where I would be

still.

O

broad and smooth the Avon

flows

By

Stratford's many

piers;

And

Shakespeare lies by Avon's

side

These

thrice a hundred

years;

But

I would be where Windrush

sweet

Laves

Burford's lovely hill--

The

grey old town on the

lonely down

Is

where I would be

still.

It

is unlike any other place,

this quaint old Burford, a

right pleasing place when

the

sun

is pouring its beams upon

the fantastic creations of the

builders of long ago,

and

when the moon is full there

is no place in England which surpasses it

in

picturesqueness.

It is very quiet and still

now, but there was a time

when Burford

cloth,

Burford wool, Burford stone,

Burford malt, and Burford

saddles were

renowned

throughout the land. Did

not the townsfolk present

two of its famous

saddles

to "Dutch William" when he

came to Burford with the

view of ingratiating

himself

into the affections of his

subjects before an important

general election? It

has

been the scene of battles.

Not far off is Battle

Edge, where the fierce

kings of

Wessex

and Mercia fought in 720 A.D. on

Midsummer Eve, in commemoration

of

which

the good folks of Burford

used to carry a dragon up and

down the streets, the

great

dragon of Wessex. Perhaps

the origin of this procession

dates back to early

pagan

days before the battle was

fought, but tradition

connects it with the

fight.

Memories

cluster thickly around one as

you walk up the old street.

It was the first

place

in England to receive the

privilege of a Merchant Guild.

The gaunt Earl of

Warwick,

the King-maker, owned the

place, and appropriated to himself the

credit

of

erecting the almshouses, though

Henry Bird gave the money.

You can still see

the

Earl's signature at the foot

of the document relating to

this foundation--R.

Warrewych--the

only signature known save

one at Belvoir. You can see the

ruined

Burford

Priory. It is not the

conventual building wherein

the monks lived in

pre-

Reformation

days and served God in the grand

old church that is Burford's

chief

glory.

Edmund Harman, the royal

barber-surgeon, received a grant of

the Priory

from

Henry VIII for curing him

from a severe illness. Then

Sir Laurence

Tanfield,

Chief

Baron of the Exchequer,

owned it, who married a

Burford lady,

Elizabeth

Cobbe.

An aged correspondent tells me

that in the days of her

youth there was

standing

a house called Cobb Hall, evidently

the former residence of

Lady

Tanfield's

family. He built a grand

Elizabethan mansion on the site of

the old

Priory,

and here was born Lucius Gary,

Lord Falkland, who was slain

in Newbury

fight.

That Civil War brought

stirring times to Burford. You

have heard of the

fame

of

the Levellers, the

discontented mutineers in Cromwell's

army, the followers

of

John

Lilburne, who for a brief

space threatened the existence of

the Parliamentary

regime.

Cromwell dealt with them

with an iron hand. He caught

and surprised them

at

Burford and imprisoned them in

the church, wherein carved

roughly on the font

with

a dagger you can see this

touching memorial of one of these

poor men:--

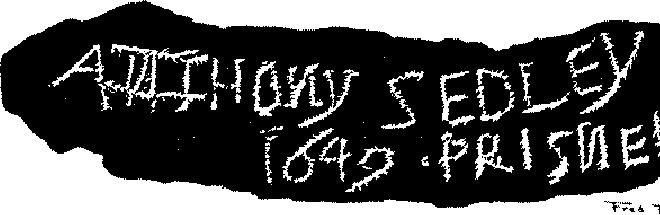

ANTHONY

SEDLEY PRISNER 1649.

Inscription

on Font, Parish Church, Burford,

Oxon

Three

of the leaders were shot in

the churchyard on the

following morning in

view

of

the other prisoners, who

were placed on the leaden roof of

the church, and you

can

still see the bullet-holes

in the old wall against

which the unhappy men

were

placed.

The following entries in the

books of the church tell the

sad story tersely:--

Burials.--"1649

Three soldiers shot to death in

Burford Churchyard

May

17th."

"Pd.

to Daniel Muncke for

cleansinge the Church when

the Levellers

were

taken 3s. 4d."

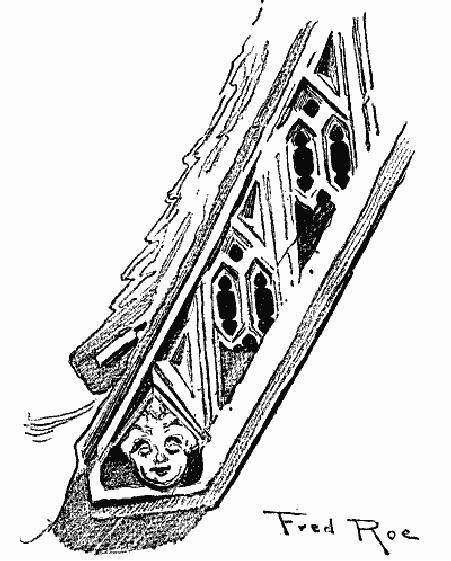

Detail

of Fifteenth-century Barge-board,

Burford, Oxon.

A

walk through the streets of

the old town is refreshing

to an antiquary's eyes.

The

old

stone buildings grey with

age with tile roofs,

the old Tolsey much

restored, the

merchants'

guild mark over many of

the ancient doorways, the

noble church with

its

eight chapels and fine tombs,

the plate of the old

corporation, now in the

custody

of

its oldest surviving member

(Burford has ceased to be an

incorporated borough),

are

all full of interest. Vandalism is

not, however, quite lacking,

even in Burford.

One

of the few Gothic chimneys

remaining, a gem with a crocketed

and pinnacled

canopy,

was taken down some thirty

years ago, while the Priory

is said to be in

danger

of being pulled down, though

a later report speaks only

of its restoration. In

the

coaching age the town was

alive with traffic, and

Burford races, established by

the

Merry Monarch, brought it

much gaiety. At the George

Inn, now degraded

from

its

old estate and cut up into

tenements, Charles I stayed. It was an

inn for more

than

a century before his time,

and was only converted from

that purpose during

the

early

years of the nineteenth century,

when the proprietor of the

Bull Inn bought it

up

and closed its doors to the public

with a view to improving the

prosperity of his

own

house. The restoration of the

picturesque almshouses founded by Henry

Bird

in

the time of the King-maker,

a difficult piece of work, was

well carried out in

the

decadent

days of the "twenties," and

happily they do not seem to

have suffered

much

in the process.

The

George Inn, Burford,

Oxon

During

our wanderings in the

streets and lanes of rural England we

must not fail to

visit

the county of Essex. It is one of the

least picturesque of our counties,

but it

possesses

much wealth of interesting

antiquities in the timber

houses at Colchester,

Saffron

Walden, the old town of

Maldon, the inns at Chigwell

and Brentwood, and

the

halls of Layer Marney and

Horsham at Thaxted. Saffron

Walden is one of those

quaint

agricultural towns whose

local trade is a thing of the

past. From the

records

which

are left of it in the shape

of prints and drawings, the

town in the early part

of

the

nineteenth century must have

been a medieval wonder. It is

useless now to rail

against

the crass ignorance and

vandalism which has swept

away so many

irreplaceable

specimens of bygone architecture

only to fill their sites

with brick

boxes,

"likely indeed and all

alike."

Itineraries

of the Georgian period when

mentioning Saffron Walden

describe the

houses

as being of "mean appearance,"16

which

remark, taking into

consideration

the

debased taste of the times,

is significant. A perfect holocaust

followed, which

extending

through that shocking time

known as the Churchwarden Period

has not

yet

spent itself in the present day.

Municipal improvements threaten to go

further

still,

and in these commercial days,

when combined capital under

such appellations

as

the "Metropolitan Co-operative" or

the "Universal Supply Stores" endeavours

to

increase

its display behind plate-glass

windows of immodest size,

the life of old

buildings

seems painfully

insecure.

A

good number of fine early

barge-boards still remain in

Saffron Walden, and

the

timber

houses which have been

allowed to remain speak only

too eloquently of the

beauties

which have vanished. One of

these structures--a large

timber building or

collection

of buildings, for the dates

of erection are various--stands in

Church

Street,

and was formerly the Sun

Inn, a hostel of much

importance in bygone

times.

This

house of entertainment is said to have

been in 1645 the quarters of

the

Parliamentary

Generals Cromwell, Ireton, and

Skippon. In 1870, during

the

conversion

of the Sun Inn into private

residences, some glazed

tiles were

discovered

bricked up in what had once been an open

hearth. These tiles

were

collectively

painted with a picture on

each side of the hearth, and

bore the

inscription

"W.E. 1730," while on one of

them a bust of the Lord

Protector was

depicted,

thus showing the tradition

to have been honoured during

the second

George's

time.17

Saffron

Walden was the rendezvous of

the Parliamentarian forces

after

the sacking of Leicester,

having their encampment on

Triplow Heath. A

remarkable

incident may be mentioned in

connexion with this fact. In

1826 a rustic,

while

ploughing some land to the

south of the town, turned up

with his share

the

brass

seal of Leicester Hospital,

which seal had doubtless

formed part of the

loot

acquired

by the rebel army.

The

Sun Inn, or "House of the

Giants," as it has sometimes been

called, from the

colossal

figures which appear in the

pargeting over its gateway,

is a building which

evidently

grew with the needs of

the town, and a study of its

architectural features

is

curiously instructive.

The

following extract from

Pepys's Diary

is

interesting as referring to

Saffron

Walden:--

"1659,

Feby. 27th. Up by four

o'clock. Mr. Blayton and I took

horse

and

straight to Saffron Walden,

where at the White Hart we

set up our

horses

and took the master to show us

Audley End House, where

the

housekeeper

showed us all the house, in

which the stateliness of

the

ceilings,

chimney-pieces, and form of the

whole was exceedingly

worth

seeing. He took us into the

cellar, where we drank

most

admirable

drink, a health to the King.

Here I played on my

flageolette,

there

being an excellent echo. He

showed us excellent pictures;

two

especially,

those of the four Evangelists

and Henry VIII. In our

going

my

landlord carried us through a

very old hospital or

almshouse, where

forty

poor people were maintained; a

very old foundation, and

over the

chimney-piece

was an inscription in brass: 'Orato

pro anim� Thomae

Bird,'

&c. They brought me a draft of

their drink in a brown bowl,

tipt

with

silver, which I drank off,

and at the bottom was a picture of

the

Virgin

with the child in her arms

done in silver. So we took

leave...."

The

inscription and the "brown

bowl" (which is a mazer cup)

still remain, but

the

picturesque

front of the hospital, built

in the reign of Edward VI,

disappeared

during

the awful "improvements"

which took place during the

"fifties." A drawing

of

it survives in the local

museum.

Maldon,

the capital of the

Blackwater district, is to the

eye of an artist a town

for

twilight

effects. The picturesque

skyline of its long,

straggling street is accentuated

in

the early morning or

afterglow, when much

undesirable detail of modern

times

below

the tiled roofs is blurred

and lost. In broad daylight the

quaintness of its

suburbs

towards the river reeks of

the salt flavour of W.W.

Jacobs's stories.

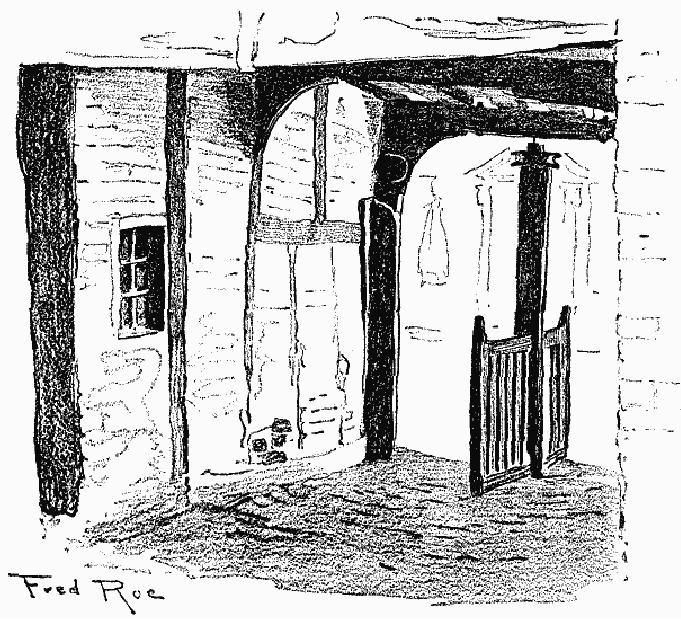

Formerly

the town was rich

with such massive timber

buildings as still appear

in

the

yard of the Blue Boar--an

ancient hostelry which was

evidently modernized

externally

in Pickwickian times. While

exploring in the outhouses of

this hostel Mr.

Roe

lighted on a venerable posting-coach of

early nineteenth-century origin

among

some

other decaying vehicles, a

curiosity even more rare

nowadays than the

Gothic

king-posts

to be seen in the picturesque

half-timbered billiard-room.

Maldon,

Essex. Sky-line of the High

Street at twilight

The

country around Maldon is

dotted plentifully with evidences of

past ages; Layer

Marney,

with its famous towers;

D'Arcy Hall, noted for

containing some of

the

finest

linen panelling in England;

Beeleigh Abbey, and other

old-world buildings.

The

sea-serpent may still be

seen at Heybridge, on the

Norman church-door, one of

the

best of its kind, and

exhibiting almost all its

original ironwork, including

the

chimerical

decorative clamp.

St.

Mary's Church, Maldon

Norman

Clamp on door of Heybridge

Church, Essex

The

ancient house exhibited at the

Franco-British Exhibition at Shepherd's

Bush

was

a typical example of an Elizabethan

dwelling. It was brought from

Ipswich,

where

it was doomed to make room for the

extension of Co-operative Stores, but

so

firmly

was it built that, in spite of

its age of three hundred and

fifty years, it defied

for

some time the attacks of the

house-breakers. It was built in 1563, as

the date

carved

on the solid lintel shows,

but some parts of the

structure may have

been

earlier.

All the oak joists and rafters had

been securely mortised into

each other and

fixed

with stout wooden pins. So

securely were these pins

fixed, that after

many

vain

attempts to knock them out,

they had all to be bored out

with augers. The

mortises

and tenons were found to be as

sound and clean as on the

day when they

were

fitted by the sixteenth-century

carpenters. The foundations and the

chimneys

were

built of brick. The house

contained a large entrance-hall, a

kitchen, a

splendidly

carved staircase, a living-room, and

two good bedrooms, on the

upper

floor.

The whole house was a fine specimen of

East Anglian half-timber

work. The

timbers

that formed the framework

were all straight, the

diamond and curved

patterns,

familiar in western counties, signs of

later construction, being

altogether

absent.

One of the striking features

of this, as of many other

timber-framed houses,

is

the carved corner or angle

post. It curves outwards as a support to

the projecting

first

floor to the extent of

nearly two feet, and the

whole piece was hewn out of

one

massive

oak log, the root, as

was usual, having been

placed upwards, and

beautifully

carved with Gothic

floriations. The full overhang of

the gables is four

feet

six inches. In later

examples this distance between

the gables and the

wall was

considerably

reduced, until at last the barge-boards

were flush with the

wall. The

joists

of the first floor project

from under a finely carved

string-course, and the end

of

each joist has a carved

finial. All the inside walls

were panelled with oak,

and

the

fire-place is of the typical

old English character, with

seats for half a

dozen

people

in the ingle-nook. The

principal room had a fine

Tudor door, and the

frieze

and

some of the panels were

enriched with an inlay of

holly. When the house

was

demolished

many of the choicest

fittings which were missing

from their places

were

found carefully stowed under

the floor boards. Possibly a

raid or a riot had

alarmed

the owners in some distant

period, and they hid their

nicest things and

then

were

slain, and no one knew of the

secret hiding-place.

Tudor

Fire-place. Now walled up in

the passage of a shop in

Banbury

The

Rector of Haughton calls

attention to a curious old house

which certainly ought

to

be preserved if it has not yet

quite vanished.

"It

is completely hidden from

the public gaze. Right away

in the fields,

to

be reached only by footpath, or by

strangely circuitous lane, in

the

parish

of Ranton, there stands a

little old half-timbered

house, known

as

the Vicarage Farm. Only a

very practised eye would

suspect the

treasures

that it contains. Entering

through the original door,

with

quaint

knocker intact, you are in

the kitchen with a fine open

fire-

place,

noble beam, and walls

panelled with oak. But

the principal

treasure

consists in what I have heard called

'The priest's room.' I

should

venture to put the date of

the house at about

1500--certainly

pre-Reformation.

How did it come to be there? and

what purpose did it

serve?

I have only been able to

find one note which can

throw any

possible

light on the matter. Gough

says that a certain Rose

(Dunston?)

brought

land at Ranton to her

husband John Doiley; and he

goes on:

'This

man had the consent of

William, the Prior of

Ranton, to erect a

chapel

at Ranton.' The little

church at Ranton has stood

there from the

thirteenth

century, as the architecture of

the west end and

south-west

doorway

plainly testify. The church

and cell (or whatever you

may call

it)

must clearly have been an

off-shoot from the Priory.

But the room:

for

this is what is principally

worth seeing. The beam is

richly

moulded,

and so is the panelling throughout. It

has a very well

carved

course

of panelling all round the

top, and this is surmounted

by an

elaborate

cornice. The stone mantelpiece is

remarkably fine and of

unusual

character. But the most

striking feature of the room

is a square

-headed

arched recess, or niche, with pierced

spandrels. What was

its

use?

It is about the right height

for a seat, and what may

have been the

seat

is there unaltered. Or was it a niche

containing a Calvary, or

some

figure?

I confess I know nothing. Is this a

unique example? I

cannot

remember

any other. But possibly

there may be others, equally

hidden

away,

comparison with which might

unfold its secret. In this

room, and

in

other parts of the house, much of

the old ironwork of hinges

and

door-fasteners

remains, and is simply excellent.

The old oak sliding

shutters

are still there, and

two more fine stone

mantelpieces; on one

hearth

the original encaustic tiles

with patterns, chiefly a

Maltese cross,

and

the oak cill surrounding

them, are in

situ. I confess I

tremble for

the

safety of this priceless relic.

The house is in a somewhat

dilapidated

condition; and I know that one

attempt was made to

buy

the

panelling and take it away.

Surely such a monument of

the past

should

be in some way guarded by the

nation."

The

beauty of English cottage-building,

its directness, simplicity, variety,

and

above

all its inevitable quality,

the intimate way in which

the buildings ally

themselves

with the soil and blend

with the ever-varied and

exquisite landscape, the

delicate

harmonies, almost musical in

their nature, that grow

from their gentle

relationship

with their surroundings, the

modulation from man's handiwork

to

God's

enveloping world that lies

in the quiet gardening that

binds one to the

other

without

discord or dissonance--all these

things are wonderfully

attractive to those

who

have eyes to see and hearts to

understand. The English

cottages have an

importance

in the story of the

development of architecture far greater

than that

which

concerns their mere beauty and

picturesqueness. As we follow the history

of

Gothic

art we find that for

the most part the

instinctive art in relation to

church

architecture

came to an end in the first

quarter of the sixteenth

century, but the

right

impulse

did not cease.

House-building went on,

though there was no

church-

building,

and we admire greatly some of those

grand mansions which were

reared

in

the time of Elizabeth and

the early Stuarts; but

art was declining, a

crumbling

taste

causing disintegration of the

sense of real beauty and

refinement of detail. A

creeping

paralysis set in later, and

the end came swiftly when

the dark days of the

eighteenth

century blotted out even

the memory of a great past.

And yet during

all

this

time the people, the

poor and middle classes, the

yeomen and farmers,

were

ever

building, building, quietly

and simply, untroubled by

any thoughts of style,

of

Gothic

art or Renaissance; hence the cottages

and dwellings of the humblest

type

maintained

in all their integrity the

real principles that made

medieval architecture

great.

Frank, simple, and direct,

built for use and not

for the establishment

of

architectural

theories, they have

transmitted their messages to

the ages and have

preserved

their beauties for the

admiration of mankind and as models

for all

time.

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION