|

OLD WALLED TOWNS |

| << THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND |

| IN STREETS AND LANES >> |

CHAPTER

III

OLD

WALLED TOWNS

The

destruction of ancient buildings

always causes grief and

distress to those who

love

antiquity. It is much to be deplored,

but in some cases is perhaps

inevitable.

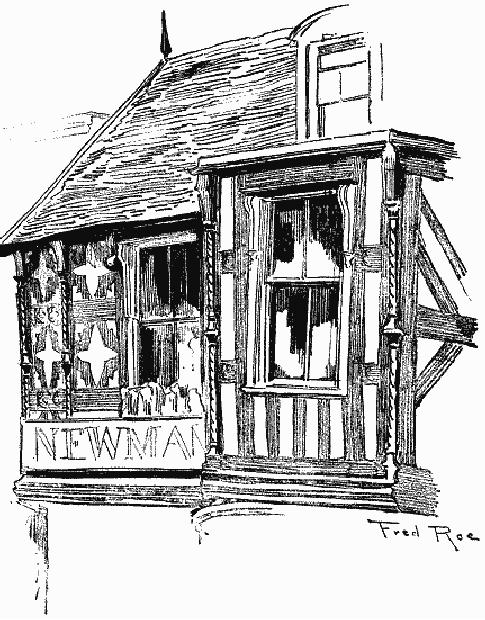

Old-fashioned

half-timbered shops with

small diamond-paned windows

are not the

most

convenient for the display

of the elegant fashionable costumes

effectively

draped

on modelled forms. Motor-cars

cannot be displayed in antiquated

old shops.

Hence

in modern up-to-date towns

these old buildings are

doomed, and have to

give

place to grand emporiums with

large plate-glass windows and the

refinements

of

luxurious display. We hope to visit

presently some of the old

towns and cities

which

happily retain their ancient

beauties, where quaint houses

with oversailing

upper

stories still exist, and with

the artist's aid to describe

many of their

attractions.

Although

much of the destruction is,

as I have said, inevitable, a

vast amount is

simply

the result of ignorance and

wilful perversity. Ignorant

persons get elected on

town

councils--worthy men doubtless, and

able men of business, who

can attend to

and

regulate the financial

affairs of the town, look

after its supply of gas and

water,

its

drainage and tramways; but they

are absolutely ignorant of

its history, its

associations,

of architectural beauty, of anything

that is not modern and

utilitarian.

Unhappily,

into the care of such

men as these is often

confided the custody

of

historic

buildings and priceless treasures, of ruined abbey and

ancient walls, of

objects

consecrated by the lapse of

centuries and by the associations of

hundreds of

years

of corporate life; and it is not

surprising that in many

cases they betray

their

trust.

They are not interested in

such things. "Let bygones be

bygones," they say.

"We

care not for old

rubbish." Moreover, they

frequently resent interference and

instruction.

Hence they destroy wholesale

what should be preserved, and

England

is

the poorer.

Not

long ago the Edwardian

wall of Berwick-on-Tweed was

threatened with

demolition

at the hands of those who ought to be

its guardians--the Corporation

of

the

town. An official from the

Office of Works, when he saw

the begrimed,

neglected

appearance of the two

fragments of this wall near

the Bell Tower, with

a

stagnant

pool in the fosse, bestrewed with

broken pitchers and rubbish,

reported

that

the Elizabethan walls of the

town which were under

the direction of the

War

Department

were in excellent condition, whereas

the Edwardian masonry

was

utterly

neglected. And why was this

relic of the town's former

greatness to be

pulled

down? Simply to clear the

site for the erection of

modern dwelling-houses.

A

very strong protest was made

against this act of municipal

barbarism by learned

societies,

the Society for the

Preservation of Ancient Buildings, and

others, and we

hope

that the hand of the

destroyer has been

stayed.

Most

of the principal towns in

England were protected by

walls, and the

citizens

regarded

it as a duty to build them and

keep them in repair. When we

look at some

of

these fortifications, their

strength, their height,

their thickness, we are

struck by

the

fact that they were

very great achievements, and that

they must have

been

raised

with immense labour and

gigantic cost. In turbulent and

warlike times they

were

absolutely necessary. Look at some of

these triumphs of medieval

engineering

skill,

so strong, so massive, able to defy the

attacks of lance and arrow, ram

or

catapult,

and to withstand ages of neglect and

the storms of a tempestuous

clime.

Towers

and bastions stood at intervals against the

wall at convenient distances, in

order

that bowmen stationed in

them could shoot down

any who attempted to

scale

the

wall with ladders anywhere

within the distance between

the towers. All along

the

wall there was a protected

pathway for the defenders to stand,

and

machicolations

through which boiling oil or

lead, or heated sand could be

poured

on

the heads of the attacking

force. The gateways were

carefully constructed,

flanked

by defending towers with a

portcullis, and a guard-room overhead

with

holes

in the vaulted roof of the

gateway for pouring down

inconvenient substances

upon

the heads of the besiegers.

There were several gates,

the usual number

being

four;

but Coventry had twelve,

Canterbury six, and Newcastle-on-Tyne

seven,

besides

posterns.

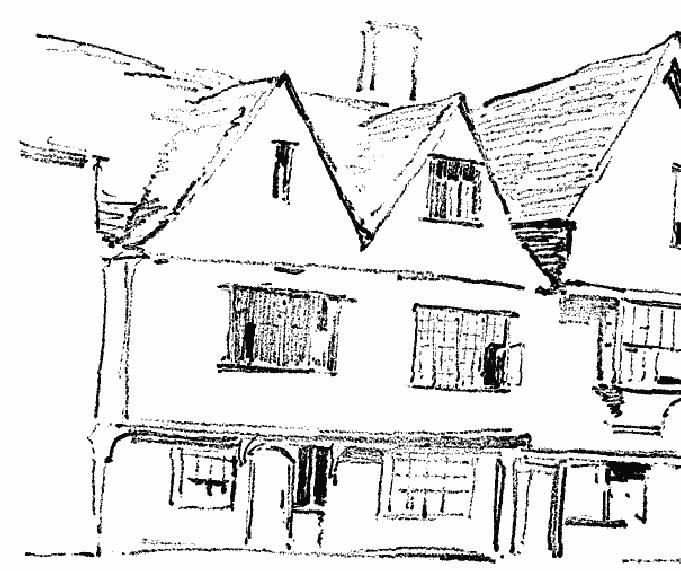

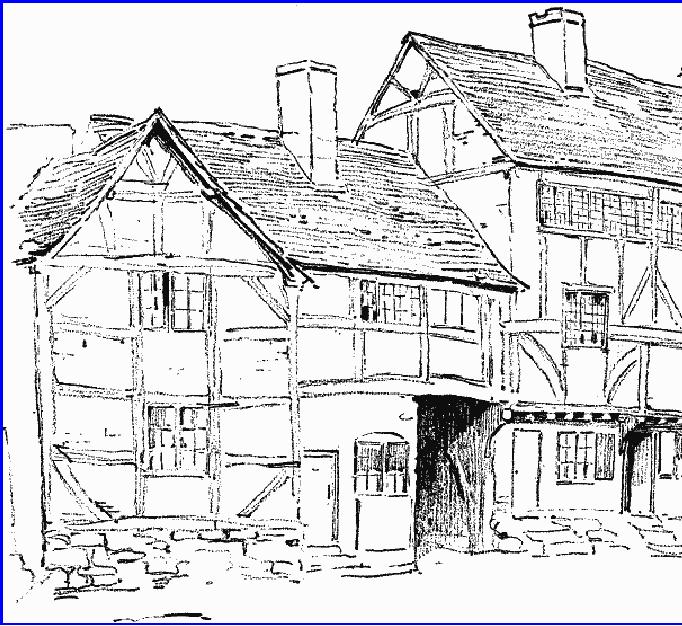

Old

Houses built on the Town Wall,

Rye

Berwick-upon-Tweed,

York, Chester, and Conway

have maintained their walls

in

good

condition. Berwick has three

out of its four gates

still standing. They

are

called

Scotchgate, Shoregate, and Cowgate, and in

the last two still

remain the

original

massive wooden gates with

their bolts and hinges. The

remaining fourth

gate,

named Bridgate, has vanished. We

have alluded to the neglect

of the

Edwardian

wall and its threatened destruction.

Conway has a wall a mile and

a

quarter

in length, with twenty-one

semicircular towers along

its course and three

great

gateways besides posterns. Edward I

built this wall in order to

subjugate the

Welsh,

and also the walls round

Carnarvon, some of which

survive, and Beaumaris.

The

name of his master-mason has been

preserved, one Henry le Elreton.

The

muniments

of the Corporation of Alnwick

prove that often great

difficulties arose

in

the matter of wall-building.

Its closeness to the

Scottish border rendered a

wall

necessary.

The town was frequently

attacked and burnt. The inhabitants

obtained a

licence

to build a wall in 1433, but

they did not at once proceed

with the work. In

1448

the Scots came and pillaged

the town, and the poor

burgesses were so robbed

and

despoiled that they could

not afford to proceed with

the wall and petitioned

the

King

for aid. Then Letters Patent

were issued for a collection

to be made for the

object,

and at last, forty years after

the licence was granted,

Alnwick got its

wall,

and

a very good wall it was--a

mile in circumference, twenty

feet in height and

six

in

thickness; "it had four

gateways--Bondgate, Clayport, Pottergate,

and

Narrowgate.

Only the first-named of

these is standing. It is three stories in

height.

Over

the central archway is a

panel on which was carved

the Brabant lion,

now

almost

obliterated. On either side is a

semi-octagonal tower. The

masonry is

composed

of huge blocks to which time

and weather have given dusky

tints. On the

front

facing the expected foes the

openings are but little

more than arrow-slits;

on

that

within, facing the town,

are well-proportioned mullioned and

transomed

windows.

The great ribbed archway is

grooved for a portcullis,

now removed, and a

low

doorway on either side gives

entrance to the chambers in the

towers. Pottergate

was

rebuilt in the eighteenth

century and crowns a steep

street; only four

corner-

stones

marked T indicate the site of

Clayport. No trace of Narrowgate

remains."4

As

the destruction of many of

our castles is due to the

action of Cromwell and

the

Parliament,

who caused them to be

"slighted" partly out of

revenge upon the

loyal

owners

who had defended them, so several of

our town-walls were thrown

down by

order

of Charles II at the Restoration on

account of the active

assistance which the

townspeople

had given to the rebels. The

heads of rebels were often placed

on

gateways.

London Bridge, Lincoln,

Newcastle, York, Berwick,

Canterbury, Temple

Bar,

and other gates have often

been adorned with these gruesome

relics of

barbarous

punishments.

How

were these strong walls

ever taken in the days

before gunpowder was

extensively

used or cannon discharged their

devastating shells? Imagine

you are

present

at a siege. You would see

the attacking force

advancing a huge

wooden

tower,

covered with hides and placed on

wheels, towards the walls.

Inside this

tower

were ladders, and when the

"sow" had been pushed towards

the wall the

soldiers

rushed up these ladders and were

able to fight on a level

with the garrison.

Perhaps

they were repulsed, and then

a shed-like structure would be

advanced

towards

the wall, so as to enable the

men to get close enough to

dig a hole beneath

the

walls in order to bring them

down. The besieged would

not be inactive, but

would

cast heavy stones on the

roof of the shed. Molten lead and

burning flax were

favourite

means of defence to alarm and frighten

away the enemy, who

retaliated

by

casting heavy stones by

means of a catapult into the

town.

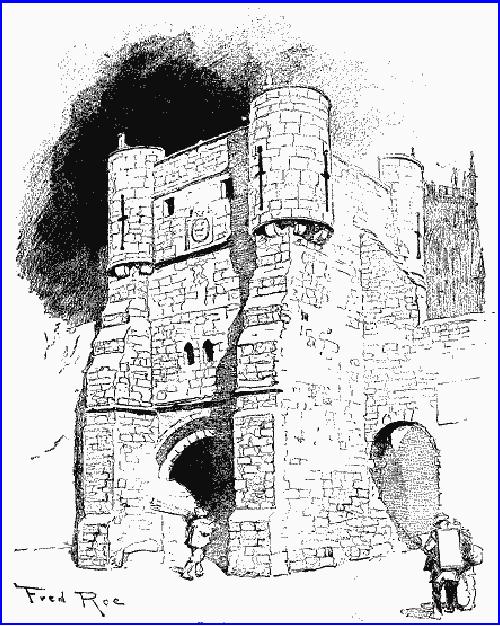

Bootham

Bar, York

Amongst

the fragments of walls still

standing, those at Newcastle are

very massive,

sooty,

and impressive. Southampton

has some grand walls

left and a gateway,

which

show how strongly the

town was fortified. The old

Cinque Port,

Sandwich,

formerly

a great and important town,

lately decayed, but somewhat

renovated by

golf,

has two gates left, and

Rochester and Canterbury have

some fragments of

their

walls standing. The repair

of the walls of towns was

sometimes undertaken by

guilds.

Generous benefactors, like

Sir Richard Whittington,

frequently contributed

to

the cost, and sometimes a tax

called murage was levied

for the purpose which

was

collected by officers named

muragers.

The

city of York has lost many

of its treasures, and the City Fathers

seem to find it

difficult

to keep their hands off such

relics of antiquity as are

left to them. There

are

few

cities in England more

deeply marked with the

impress of the storied past

than

York--the

long and moving story of

its gates and walls, of the

historical

associations

of the city through century

after century of English

history. About

eighty

years ago the Corporation

destroyed the picturesque

old barbicans of the

Bootham,

Micklegate, and Monk Bars, and

only one, Walmgate, was

suffered to

retain

this interesting feature. It is a

wonder they spared those

curious stone half-

length

figures of men, sculptured in a

menacing attitude in the act of

hurling large

stones

downwards, which vaunt

themselves on the summit of

Monk Bar--probably

intended

to deceive invaders--or that interesting

stone platform only

twenty-two

inches

wide, which was the only

foothold available for the

martial burghers who

guarded

the city wall at Tower

Place. A year or two ago

the City Fathers decided,

in

order to provide work for

the unemployed, to interfere

with the city moats

by

laying

them out as flower-beds and by

planting shrubs and making

playgrounds of

the

banks. The protest of the

Yorks Arch�ological Society, we

believe, stayed their

hands.

The

same story can be told of

far too many towns and

cities. A few years

ago

several

old houses were demolished

in the High Street of the

city of Rochester to

make

room for electric tramways.

Among these was the old

White Hart Inn, built

in

1396,

the sign being a badge of

Richard II, where Samuel

Pepys stayed. He found

that

"the beds were corded, and we had no

sheets to our beds, only

linen to our

mouths"

(a narrow strip of linen to

prevent the contact of the

blanket with the

face).

With

regard to the disappearance of old

inns, we must wait until we

arrive at

another

chapter.

We

will now visit some old

towns where we hope to discover

some buildings that

are

ancient and where all is

not distressingly new,

hideous, and commonplace.

First

we

will travel to the old-world

town of Lynn--"Lynn Regis, vulgarly

called King's

Lynn,"

as the royal charter of

Henry VIII terms it. On the

land side the town

was

defended

by a fosse, and there are

still considerable remains of

the old wall,

including

the fine Gothic South Gates.

In the days of its ancient

glory it was known

as

Bishop's Lynn, the town

being in the hands of the

Bishop of Norwich.

Bishop

Herbert

de Losinga built the church

of St. Margaret at the

beginning of the

twelfth

century,

and gave it with many privileges to

the monks of Norwich, who

held a

priory

at Lynn; and Bishop Turbus

did a wonderfully good stroke of

business,

reclaimed

a large tract of land about

1150 A.D., and amassed

wealth for his

see

from

his markets, fairs, and

mills. Another bishop,

Bishop Grey, induced

or

compelled

King John to grant a free

charter to the town, but

astutely managed to

keep

all the power in his

own hands. Lynn was always a very

religious place, and

most

of the orders--Benedictines, Franciscans,

Dominicans, Carmelite and

Augustinian

Friars, and the Sack

Friars--were represented at Lynn, and

there were

numerous

hospitals, a lazar-house, a college of

secular canons, and other

religious

institutions,

until they were all

swept away by the greed of a

rapacious king. There

is

not much left to-day of

all these religious

foundations. The latest

authority on the

history

of Lynn, Mr. H.J. Hillen,

well says: "Time's unpitying

plough-share has

spared

few vestiges of their architectural

grandeur."

A cemetery cross in

the

museum,

the name "Paradise" that keeps up

the remembrance of the cool,

verdant

cloister-garth,

a brick arch upon the

east bank of the Nar, and a

similar gateway in

"Austin"

Street are all the relics

that remain of the old

monastic life, save

the

slender

hexagonal "Old Tower," the

graceful lantern of the

convent of the grey-

robed

Franciscans. The above writer also points

out the beautifully carved

door in

Queen

Street, sole relic of the

College of Secular Canons, from

which the chisel of

the

ruthless iconoclast has

chipped off the obnoxious

Orate

pro anima.

The

quiet, narrow, almost

deserted streets of Lynn,

its port and quays have

another

story

to tell. They proclaim its

former greatness as one of the

chief ports in

England

and

the centre of vast

mercantile activity. A thirteenth-century

historian, Friar

William

Newburg, described Lynn as "a noble

city noted for its

trade." It was the

key

of Norfolk. Through it flowed

all the traffic to and

from northern East

Anglia,

and

from its harbour crowds of

ships carried English produce,

mainly wool, to the

Netherlands,

Norway, and the Rhine

Provinces. Who would have

thought that this

decayed

harbour ranked fourth among

the ports of the kingdom?

But its glories

have

departed. Decay set in. Its

prosperity began to

decline.

Railways

have been the ruin of

King's Lynn. The merchant

princes who once

abounded

in the town exist here no

longer. The last of the

long race died quite

recently.

Some ancient ledgers still

exist in the town, which

exhibit for one firm

alone

a turnover of something like a

million and a half sterling

per annum.

Although

possessed of a similarly splendid

waterway, unlike Ipswich,

the trade of

the

town seems to have quite

decayed. Few signs of commerce are

visible, except

where

the advent of branch

stations of enterprising "Cash"

firms has resulted in

the

squaring

up of odd projections and consequent

overthrow of certain

ancient

buildings.

There is one act of vandalism which

the town has never

ceased to regret

and

which should serve as a warning

for the future. This is

the demolition of the

house

of Walter Coney, merchant, an

unequalled specimen of

fifteenth-century

domestic

architecture, which formerly stood at

the corner of the Saturday

Market

Place

and High Street. So strongly was this

edifice constructed that it was

with the

utmost

difficulty that it was taken to

pieces, in order to make room

for the ugly

range

of white brick buildings

which now stands upon

its site. But Lynn had an

era

of

much prosperity during the

rise of the Townshends, when

the agricultural

improvements

brought about by the second

Viscount introduced much

wealth to

Norfolk.

Such buildings as the Duke's

Head Hotel belong to the

second Viscount's

time,

and are indicative of the

influx of visitors which the

town enjoyed. In the

present

day this hotel, though

still a good-sized establishment, occupies

only half

the

building which it formerly

did. An interesting oak staircase of

fine proportions,

though

now much warped, may be

seen here.

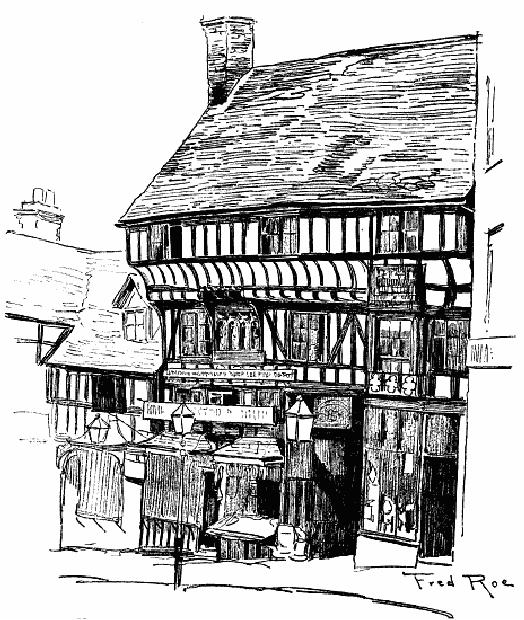

Half-timbered

House with early

Fifteenth-century Doorway, King's

Lynn, Norfolk

In

olden days the Hanseatic League had an

office here. The Jews

were plentiful and

supplied

capital--you can find their

traces in the name of the

"Jews' Lane Ward"--

and

then came the industrious

Flemings, who brought with

them the art of

weaving

cloth

and peculiar modes of building houses, so

that Lynn looks almost like

a little

Dutch

town. The old guild

life of Lynn was strong and vigorous,

from its Merchant

Guild

to the humbler craft guilds,

of which we are told that

there have been no

less

than

seventy-five. Part of the old

Guildhall, erected in 1421,

with its chequered

flint

and

stone gable still stands facing

the market of St. Margaret

with its Renaissance

porch,

and a bit of the guild

hall of St. George the

Martyr remains in King

Street.

The

custom-house, which was

originally built as an exchange

for the Lynn

merchants,

is a notable building, and has a statue

of Charles II placed in a niche.

This

was the earliest work of a

local architect, Henry Bell,

who is almost

unknown.

He

was mayor of King's Lynn, and

died in 1717, and his memory

has been saved

from

oblivion by Mr. Beloe of that

town, and is enshrined in Mr.

Blomfield's

History

of Renaissance Architecture:--

"This

admirable little building

originally consisted of an open

loggia

about

40 feet by 32 feet outside,

with four columns down

the centre,

supporting

the first floor, and an

attic storey above. The

walls are of

Portland

stone, with a Doric order to

the ground storey supporting

an

Ionic

order to the first floor.

The cornice is of wood, and

above this is a

steep-pitched

tile roof with dormers,

surmounted by a balustrade

inclosing

a flat, from which rises a

most picturesque wooden

cupola.

The

details are extremely

refined, and the technical

knowledge and

delicate

sense of scale and proportion

shown in this building

are

surprising

in a designer who was under thirty, and

is not known to have

done

any previous work."5

A

building which the town

should make an effort to preserve is the

old "Greenland

Fishery

House," a tenement dating

from the commencement of the

seventeenth

century.

The

Duke's Head Inn, erected in

1689, now spoilt by its

coating of plaster, a house

in

Queen's Street, the old market cross,

destroyed in 1831 and sold for

old

materials,

and the altarpieces of the

churches of St. Margaret and

St. Nicholas,

destroyed

during "restoration," and

North Runcton church, three

miles from Lynn,

are

other works of this very

able artist.

Until

the Reformation Lynn was known as

Bishop's Lynn, and galled

itself under

the

yoke of the Bishop of

Norwich; but Henry freed

the townsfolk from

their

bondage

and ordered the name to be changed to Lynn Regis.

Whether the good

people

throve better under the

control of the tyrant who

crushed all their guilds

and

appropriated

the spoil than under

the episcopal yoke may be

doubtful; but the

change

pleased them, and with

satisfaction they placed the

royal arms on their

East

Gate,

which, after the manner of

gates and walls, has been

pulled down. If you

doubt

the former greatness of this

old seaport you must

examine its civic plate.

It

possesses

the oldest and most

important and most beautiful specimen of

municipal

plate

in England, a grand, massive silver-gilt

cup of exquisite workmanship. It

is

called

"King John's Cup," but it

cannot be earlier than the

reign of Edward III. In

addition

to this there is a superb sword of

state of the time of Henry

VIII, another

cup,

four silver maces, and other

treasures. Moreover, the town had a

famous

goldsmiths'

company, and several specimens of

their handicraft remain.

The

defences

of the town were sorely

tried in the Civil War,

when for three weeks

it

sustained

the attacks of the rebels. The

town was forced to surrender, and

the poor

folk

were obliged to pay ten

shillings a head, besides a

month's pay to the

soldiers,

in

order to save their homes

from plunder. Lynn has many

memories. It sheltered

King

John when fleeing from

the revolting barons, and kept

his treasures until

he

took

them away and left them in a

still more secure place

buried in the sands of

the

Wash.

It welcomed Queen Isabella

during her retirement at Castle

Rising,

entertained

Edward IV when he was hotly

pursued by the Earl of

Warwick, and has

been

worthy of its name as a loyal

king's town.

Another

walled town on the Norfolk

coast attracts the attention

of all who love

the

relics

of ancient times, Great

Yarmouth, with its wonderful

record of triumphant

industry

and its associations with many great

events in history. Henry

III,

recognizing

the important strategical

position of the town in

1260, granted a

charter

to

the townsfolk empowering

them to fortify the place

with a wall and a moat,

but

more

than a century elapsed

before the fortifications

were completed. This

was

partly

owing to the Black Death,

which left few men in

Yarmouth to carry on

the

work.

The walls were built of

cut flint and Caen stone, and

extended from the

north

-east

tower in St. Nicholas

Churchyard, called King

Henry's Tower, to

Blackfriars

Tower

at the south end, and

from the same King

Henry's Tower to the

north-west

tower

on the bank of the Bure.

Only a few years ago a large

portion of this, north

of

Ramp

Row, now called Rampart

Road, was taken down, much

to the regret of

many.

And here I may mention a

grand movement which might

be with advantage

imitated

in every historic town. A

small private company has

been formed called

the

"Great Yarmouth Historical

Buildings, Limited." Its

object is to acquire and

preserve

the relics of ancient

Yarmouth. The founders

deserve the highest praise

for

their

public spirit and patriotism. How

many cherished objects in

Vanishing

England

might have been preserved if

each town or county

possessed such a

valuable

association! This Yarmouth society

owns the remains of the

cloisters of

Grey

Friars and other remains of

ancient buildings. It is only to be

regretted that it

was

not formed earlier. There

were nine gates in the

walls of the town, but

none of

them

are left, and of the sixteen

towers which protected the

walls only a very

few

remain.

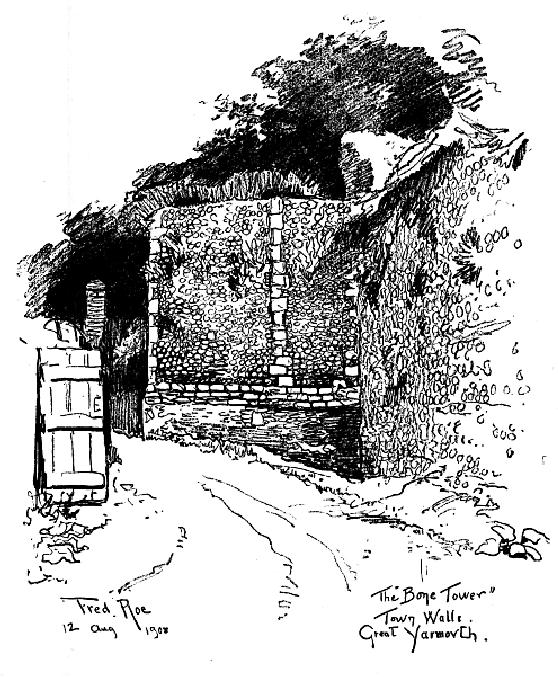

The

"Bone Tower", Town walls,

Great Yarmouth

These

walls guard much that is

important. The ecclesiastical buildings

are very

fine,

including the largest parish

church in England, founded by

the same Herbert

de

Losinga whose good work we saw at

King's Lynn. The church of

St. Nicholas

has

had many vicissitudes, and is now one of

the finest in the country.

It was in

medieval

times the church of a

Benedictine Priory; a cell of

the monastery at

Norwich

and the Priory Hall remains,

and is now restored and used as a

school.

Royal

guests have been entertained

there, but part of the

buildings were turned

into

cottages

and the great hall into stables. As we

have said, part of the

Grey Friars

Monastery

remains, and also part of the house of

the Augustine Friars.

The

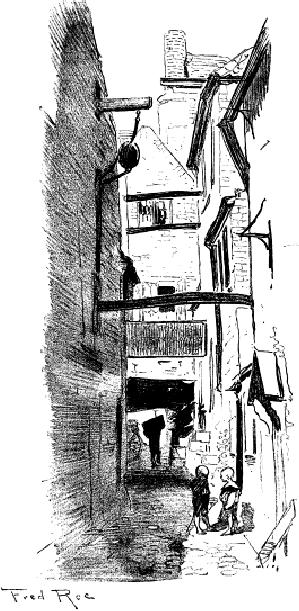

Yarmouth

rows are a great feature of

the town. They are

not like the Chester

rows,

but

are long, narrow streets

crossing the town from

east to west, only six

feet wide,

and

one row called Kitty-witches

only measures at one end two

feet three inches. It

has

been suggested that this

plan of the town arose

from the fishermen hanging

out

their

nets to dry and leaving a narrow

passage between each other's

nets, and that in

course

of time these narrow

passages became defined and

were permanently

retained.

In former days rich merchants and traders

lived in the houses that

line

these

rows, and had large gardens

behind their dwellings; and sometimes

you can

see

relics of former greatness--a

panelled room or a richly decorated

ceiling. But

the

ancient glory of the rows is

past, and the houses are

occupied now by

fishermen

or

labourers. These rows are so

narrow that no ordinary

vehicle could be

driven

along

them. Hence there arose

special Yarmouth carts about three and a

half feet

wide

and twelve feet long

with wheels underneath the

body. Very brave and

gallant

have

always been the fishermen of

Yarmouth, not only in

fighting the elements,

but

in

defeating the enemies of

England. History tells of

many a sea-fight in which

they

did

good service to their king and

country. They gallantly

helped to win the

battle

of

Sluys, and sent forty-three ships and one

thousand men to help with

the siege of

Calais

in the time of Edward III.

They captured and burned

the town and harbour

of

Cherbourg

in the time of Edward I, and

performed many other acts of

daring.

Row

No. 83, Great

Yarmouth

One

of the most interesting

houses in the town is the

Tolhouse, the centre of

the

civic

life of Yarmouth. It is said to be

six hundred years old,

having been erected

in

the

time of Henry III, though

some of the windows are

decorated, but may

have

been

inserted later. Here the

customs or tolls were

collected, and the

Corporation

held

its meetings. There is a

curious open external staircase

leading to the first

floor,

where the great hall is

situated. Under the hall is

a gaol, a wretched

prison

wherein

the miserable captives were

chained to a beam that ran

down the centre.

Nothing

in the town bears stronger

witness to the industry and perseverance

of the

Yarmouth

men than the harbour.

They have scoured the sea

for a thousand years to

fill

their nets with its spoil,

and made their trade of world-wide

fame, but their

port

speaks

louder in their praise.

Again and again has the

fickle sea played havoc

with

their

harbour, silting it up with

sand and deserting the

town as if in revenge for

the

harvest

they reap from her.

They have had to cut out no

less than seven harbours

in

the

course of the town's existence,

and royally have they

triumphed over all

difficulties

and made Yarmouth a great and prosperous

port.

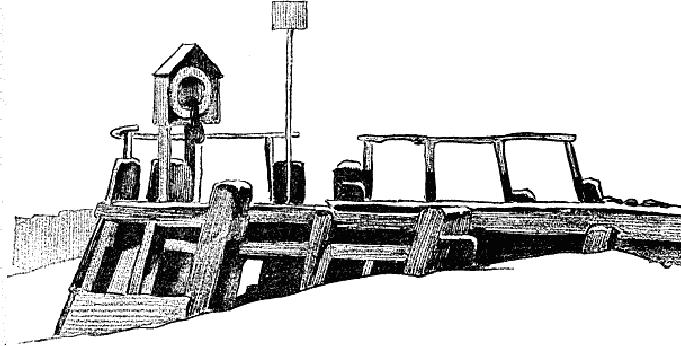

Near

Yarmouth is the little port

of Gorleston with its old

jetty-head, of which we

give

an illustration. It was once the rival of

Yarmouth. The old

magnificent church

of

the Augustine Friars stood in

this village and had a

lofty, square,

embattled

tower

which was a landmark to sailors.

But the church was unroofed

and despoiled

at

the Reformation, and its

remains were pulled down in

1760, only a small

portion

of

the tower remaining, and

this fell a victim to a

violent storm at the

beginning of

the

last century. The grand

parish church was much

plundered at the

Reformation,

and

left piteously bare by the

despoilers.

The

Old Jetty, Gorleston

The

town, now incorporated with

Yarmouth, has a proud

boast:--

Gorleston

was Gorleston ere Yarmouth

begun,

And

will be Gorleston when Yarmouth is

done.

Another

leading East Anglian port in

former days was the county

town of Suffolk,

Ipswich.

During the thirteenth and

fourteenth centuries ships from

most of the

countries

of Western Europe disembarked their

cargoes on its quays--wines

from

Spain,

timber from Norway, cloth

from Flanders, salt from

France, and "mercerie"

from

Italy left its crowded

wharves to be offered for

sale in the narrow, busy

streets

of

the borough. Stores of fish

from Iceland, bales of wool,

loads of untanned hides,

as

well as the varied

agricultural produce of the

district, were exposed twice

in the

week

on the market stalls.6

The

learned editor of the

Memorials

of Old Suffolk,

who

knows

the old town so well,

tells us that the stalls of

the numerous markets

lay

within

a narrow limit of space near

the principal churches of

the town--St. Mary-le

-Tower,

St. Mildred, and St.

Lawrence. The Tavern Street of

to-day was the site of

the

flesh market or cowerye. A

narrow street leading thence to

the Tower Church

was

the Poultry, and Cooks' Row,

Butter Market, Cheese and

Fish markets were in

the

vicinity. The manufacture of

leather was the leading

industry of old

Ipswich,

and

there was a goodly company of

skinners, barkers, and tanners employed

in the

trade.

Tavern Street had, as its name

implies, many taverns, and was

called the

Vintry,

from the large number of

opulent vintners who carried

on their trade with

London

and Bordeaux. Many of these

men were not merely

peaceful merchants,

but

fought with Edward III in

his wars with France and

were knighted for

their

feats

of arms. Ipswich once boasted of a castle

which was destroyed in

Stephen's

reign.

In Saxon times it was fortified by a

ditch and a rampart which

were

destroyed

by the Danes, but the

fortifications were renewed in

the time of King

John,

when a wall was built round

the town with four

gates which took their

names

from

the points of the compass.

Portions of these remain to

bear witness to the

importance

of this ancient town. We

give views of an old

building near the

custom-

house

in College Street and Fore Street,

examples of the narrow,

tortuous

thoroughfares

which modern improvements

have not swept

away.

Tudor

House, Ipswich, near the

Custom House

Three-gabled

House, Fore Street,

Ipswich

We

cannot give accounts of all

the old fortified towns in

England and can only

make

selections. We have alluded to

the ancient walls of York.

Few cities can

rival

it

in interest and architectural beauty,

its relics of Roman times,

its stately and

magnificent

cathedral, the beautiful

ruins of St. Mary's Abbey,

the numerous

churches

exhibiting all the grandeur

of the various styles of

Gothic architecture,

the

old

merchants' hall, and the

quaint old narrow streets

with gabled houses and

widely

projecting storeys. And then

there is the varied history

of the place dating

from

far-off Roman times. Not

the least interesting feature of York

are its gates and

walls.

Some parts of the walls are

Roman, that curious

thirteen-sided building

called

the multangular tower

forming part of it, and also

the lower part of the

wall

leading

from this tower to Bootham

Bar, the upper part

being of later origin.

These

walls

have witnessed much

fighting, and the cannons in

the Civil War during

the

siege

in 1644 battered down some portions of

them and sorely tried their

hearts.

But

they have been kept in good

preservation and repaired at times, and

the part on

the

west of the Ouse is especially

well preserved. You can see

some Norman and

Early

English work, but the

bulk of it belongs to Edwardian

times, when York

played

a great part in the history of

England, and King Edward I

made it his capital

during

the war with Scotland, and

all the great nobles of

England sojourned

there.

Edward

II spent much time there, and

the minster saw the marriage

of his son.

These

walls were often sorely

needed to check the inroads

of the Scots. After

Bannockburn

fifteen thousand of these

northern warriors advanced to the

gates of

York.

The four gates of the

city are very remarkable.

Micklegate Bar consists of a

square

tower built over a circular

arch of Norman date with

embattled turrets at

the

angles.

On it the heads of traitors

were formerly exposed. It bears on

its front the

arms

of France as well as those of

England.

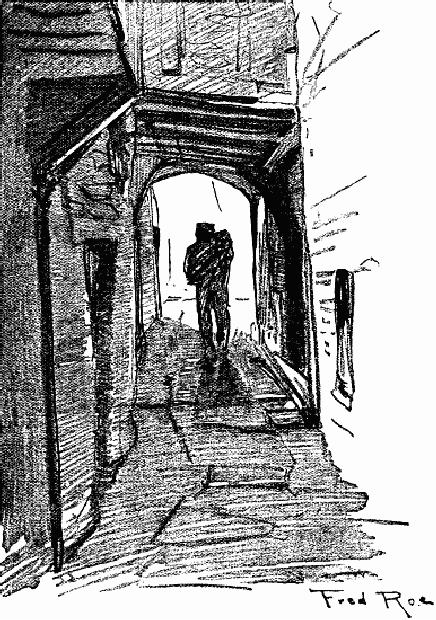

"Melia's

Passage," York

Bootham

Bar is the main entrance

from the north, and has a

Norman arch with

later

additions

and turrets with narrow

slits for the discharge of

arrows. It saw the

burning

of the suburb of Bootham in 1265 and

much bloodshed, when a

mighty

quarrel

raged between the citizens

and the monks of the Abbey

of St. Mary owing

to

the abuse of the privilege

of sanctuary possessed by the

monastery. Monk Bar

has

nothing to do with monks.

Its former name was

Goodramgate, and after

the

Restoration

it was changed to Monk Bar in honour of

General Monk. The

present

structure

was probably built in the

fourteenth century. Walmgate

Bar, a strong,

formidable

structure, was built in the

reign of Edward I, and as we have said,

it is

the

only gate that retains

its curious barbican,

originally built in the time

of Edward

III

and rebuilt in 1648. The

inner front of the gate

has been altered from

its original

form

in order to secure more

accommodation within. The

remains of the

Clifford's

Tower,

which played an important

part in the siege, tell of

the destruction

caused

by

the blowing up of the

magazine in 1683, an event

which had more the

appearance

of design than accident. York abounds

with quaint houses and

narrow

streets.

We give an illustration of the

curious Melia's Passage; the

origin of the

name

I am at a loss to conjecture.

Chester

is, we believe, the only

city in England which has

retained the entire

circuit

of

its walls complete.

According to old unreliable legends,

Marius, or Marcius,

King

of the British, grandson of

Cymbeline, who began his

reign A.D. 73,

first

surrounded

Chester with a wall, a mysterious person

who must be classed

with

Leon

Gawr, or Vawr, a mighty

strong giant who founded

Chester, digging

caverns

in

the rocks for habitations,

and with the story of King

Leir, who first made

human

habitations

in the future city. Possibly

there was here a British camp. It

was

certainly

a Roman city, and has

preserved the form and plan

which the Romans

were

accustomed to affect; its four

principal streets diverging at

right angles from a

common

centre, and extending north,

east, south, and west, and

terminating in a

gate,

the other streets forming

insul� as at Silchester. There is

every reason to

believe

that the Romans surrounded

the city with a wall.

Its strength was

often

tried.

Hither the Saxons came under

Ethelfrith and pillaged the

city, but left it to

the

Britons,

who were not again dislodged

until Egbert came in 828 and

recovered it.

The

Danish pirates came here and

were besieged by Alfred, who

slew all within

its

walls.

These walls were standing

but ruinous when the

noble daughter of

Alfred,

Ethelfleda,

restored them in 907. A volume

would be needed to give a full

account

of

Chester's varied history, and our

main concern is with the

treasures that

remain.

The

circumference of the walls is

nearly two miles, and there

are four principal

gates

besides posterns--the North,

East, Bridge-gate, and Water-gate.

The North

Gate

was in the charge of the

citizens; the others were

held by persons who had

that

office

by serjeanty under the Earls

of Chester, and were entitled to

certain tolls,

which,

with the custody of the

gates, were frequently purchased by

the Corporation.

The

custody of the Bridge-gate

belonged to the Raby family

in the reign of

Edward

III.

It had two round towers, on

the westernmost of which was an

octagonal water-

tower.

These were all taken down in

1710-81 and the gate

rebuilt. The East

Gate

was

given by Edward I to Henry

Bradford, who was bound to

find a crannoc and a

bushel

for measuring the salt

that might be brought in.

Needless to say, the old

gate

has

vanished. It was of Roman architecture,

and consisted of two arches formed

by

large

stones. Between the tops of the arches,

which were cased with

Norman

masonry,

was the whole-length figure of a

Roman soldier. This gate was

a porta

principalis,

the termination of the great

Watling Street that led from

Dover through

London

to Chester. It was destroyed in 1768, and

the present gate erected by

Earl

Grosvenor.

The custody of the

Water-gate belonged to the

Earls of Derby. It also

was

destroyed, and the present arch

erected in 1788. A new North

Gate was built in

1809

by Robert, Earl Grosvenor.

The principal postern-gates were Cale

Yard Gate,

made

by the abbot and convent in the

reign of Edward I as a passage to

their

kitchen

garden; New-gate, formerly

Woolfield or Wolf-gate, repaired in 1608,

also

called

Pepper-gate;7

and

Ship-gate, or Hole-in-the-wall, which

alone retains its

Roman

arch, and leads to a ferry

across the Dee.

The

walls are strengthened by

round towers so placed as not to be

beyond bowshot

of

each other, in order that

their arrows might reach the

enemy who should

attempt

to

scale the walls in the

intervals. At the north-east

corner is Newton's

Tower,

better

known as the Phoenix from a

sculptured figure, the

ensign of one of the

city

guilds,

appearing over its door.

From this tower Charles I

saw the battle of

Rowton

Heath

and the defeat of his troops

during the famous siege of

Chester. This was one

of

the most prolonged and

deadly in the whole history

of the Civil War. It

would

take

many pages to describe the

varied fortunes of the

gallant Chester men,

who

were

at length constrained to feed on horses,

dogs, and cats. There is

much in the

city

to delight the antiquary and

the artist--the famous rows,

the three-gabled old

timber

mansion of the Stanleys with

its massive staircase, oaken floors,

and

panelled

walls, built in 1591, Bishop

Lloyd's house in Water-gate with

its timber

front

sculptured with Scripture

subjects, and God's Providence House

with its

motto

"God's Providence is mine

inheritance," the inhabitants of

which are said to

have

escaped one of the terrible plagues

that used to rage frequently

in old Chester.

Detail

of Half-timbered House in High

Street, Shrewsbury

Journeying

southwards we come to Shrewsbury, another

walled town,

abounding

with

delightful half-timbered houses, less

spoiled than any town we

know. It was

never

a Roman town, though six

miles away, at Uriconium,

the Romans had a

flourishing

city with a great basilica,

baths, shops, and villas, and the

usual

accessories

of luxury. Tradition says

that its earliest Celtic

name was Pengwern,

where

a British prince had his palace;

but the town Scrobbesbyrig

came into

existence

under Offa's rule in Mercia,

and with the Normans came

Roger de

Montgomery,

Shrewsbury's first Earl, and

a castle and the stately abbey of

SS.

Peter

and Paul. A little later the

town took to itself walls,

which were abundantly

necessary

on account of the constant

inroads of the wild

Welsh.

For

the barbican's massy and high,

Bloudie

Jacke!

And

the oak-door is heavy and

brown;

And

with iron it's plated

and machicolated,

To

pour boiling oil and lead

down;

How

you'd frown

Should

a ladle-full fall on your

crown!

The

rock that it stands on is

steep,

Bloudie

Jacke!

To

gain it one's forced for to

creep;

The

Portcullis is strong, and the

Drawbridge is long,

And

the water runs all

round the Keep;

At

a peep

You

can see that the moat's very

deep!

So

rhymed the author of the

Ingoldsby

Legends, when in

his "Legend of

Shropshire"

he described the red stone fortress

that towers over the

loop of the

Severn

enclosing the picturesque

old town of Shrewsbury. The

castle, or rather its

keep,

for the outworks have

disappeared, has been

modernized past

antiquarian

value

now. Memories of its

importance as the key of the

Northern Marches, and of

the

ancient custom of girding

the knights of the shire

with their swords by

the

sheriffs

on the grass plot of its

inner court, still remain.

The town now stands on

a

peninsula

girt by the Severn. On the

high ground between the

narrow neck stood

the

castle, and under its shelter

most of the houses of the

inhabitants. Around

this

was

erected the first wall.

The latest historian of

Shrewsbury8

tells us

that it started

from

the gate of the castle,

passed along the ridge at

the back of Pride Hill, at

the

bottom

of which it turned along the

line of High Street, past

St. Julian's Church

which

overhung it, to the top of

Wyle Cop, when it followed

the ridge back to the

castle.

Of the part extending from

Pride Hill to Wyle Cop only scant traces

exist at

the

back of more modern

buildings.

The

town continued to grow and

more extensive defences were

needed, and in the

time

of Henry III, Mr. Auden states

that this followed the

old line at the back

of

Pride

Hill, but as the ground

began to slope downwards, another

wall branched

from

it in the direction of Roushill and

extended to the Welsh

Bridge. This became

the

main defence, leaving the

old wall as an inner

rampart. From the Welsh

Bridge

the

new wall turned up Claremont

Bank to where St. Chad's

Church now stands,

and

where one of the original

towers stood. Then it passed

along Murivance,

where

the

only existing tower is to be

seen, and so along the still

remaining portion of

the

wall

to English Bridge, where it

turned up the hill at the

back of what is now

Dogpole,

and passing the Watergate,

again joined the fortifications of

the castle.9

The

castle itself was reconstructed by Prince

Edward, the son of Henry III, at

the

end

of the thirteenth century,

and is of the Edwardian type

of concentric castle. The

Norman

keep was incorporated within a

larger circle of tower and

wall, forming an

inner

bailey; besides this there

was formerly an outer bailey, in

which were various

buildings,

including the chapel of St.

Nicholas. Only part of the

buildings on one

side

of the inner bailey remains

in its original form, but

the massive character of the

whole

may be judged from the

fragments now

visible.

These

walls guarded a noble town full of

churches and monasteries,

merchants'

houses,

guild halls, and much else.

We will glance at the beauties

that remain: St.

Mary's,

containing specimens of every

style of architecture from

Norman

downward,

with its curious foreign

glass; St. Julian's, mainly

rebuilt in 1748,

though

the old tower remains;

St. Alkmund's; the Church of

St. Chad; St.

Giles's

Church;

and the nave and refectory

pulpit of the monastery of

SS. Peter and Paul.

It

is

distressing to see this

interesting gem of fourteenth-century

architecture amid the

incongruous

surroundings of a coalyard. You can find

considerable remains of

the

domestic

buildings of the Grey

Friars' Monastery near the

footbridge across the

Severn,

and also of the home of the

Austin Friars in a builder's

yard at the end of

Baker

Street.

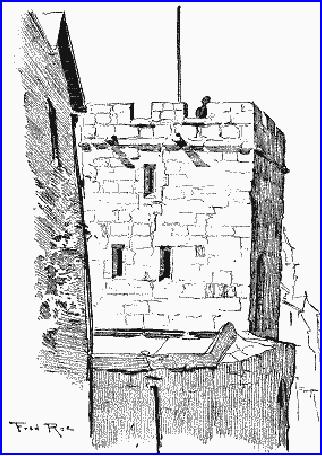

Tower

on the Town Wall,

Shrewsbury

In

many towns we find here and

there an old half-timbered

dwelling, but in

Shrewsbury

there is a surprising wealth of

them--streets full of them, bearing

such

strange

medieval names as "Mardel" or

"Wyle Cop." Shrewsbury is

second to no

other

town in England in the

interest of its ancient

domestic buildings. There is

the

gatehouse

of the old Council House,

bearing the date 1620,

with its high gable

and

carved

barge-boards, its panelled front,

the square spaces between

the upright and

horizontal

timbers being ornamented

with cut timber. The

old buildings of the

famous

Shrewsbury School are now

used as a Free Library and

Museum and

abound

in interest. The house remains in

which Prince Rupert stayed

during his

sojourn

in 1644, then owned by

"Master Jones the lawyer,"

at the west end of

St.

Mary's

Church, with its fine

old staircase. Whitehall, a

fine mansion of red

sandstone,

was built by Richard Prince, a

lawyer, in 1578-82, "to his

great chardge

with

fame to hym and hys

posterite for ever." The

Old Market Hall in

the

Renaissance

style, with its mixture of

debased Gothic and classic details, is

worthy

of

study. Even in Shrewsbury we

have to record the work of

the demon of

destruction.

The erection of the New

Market Hall entailed the

disappearance of

several

old picturesque houses. Bellstone

House, erected in 1582, is

incorporated in

the

National Provincial Bank.

The old mansion known as

Vaughan's Place is

swallowed

up by the music-hall, though

part of the ancient

dwelling-place remains.

St.

Peter's Abbey Church in the

commencement of the nineteenth

century had an

extraordinary

annexe of timber and plaster,

probably used at one time as

parsonage

house,

which, with several buttressed

remains of the adjacent

conventual buildings,

have

long ago been squared up

and "improved" out of

existence. Rowley's

mansion,

in

Hill's Lane, built of brick

in 1618 by William Rowley, is now a

warehouse.

Butcher

Row has some old

houses with projecting

storeys, including a

fine

specimen

of a medieval shop. Some of

the houses in Grope Lane

lean together from

opposite

sides of the road, so that people in

the highest storey can

almost shake

hands

with their neighbours across

the way. You can see the

"Olde House" in

which

Mary Tudor is said to have

stayed, and the mansion of the

Owens, built in

1592

as an inscription tells us, and

that of the Irelands, with

its range of bow-

windows,

four storeys high, and

terminating in gables, erected

about 1579. The

half

-timbered

hall of the Drapers' Guild,

some old houses in

Frankwell, including

the

inn

with the quaint sign--the

String of Horses, the ancient

hostels--the Lion,

famous

in the coaching age, the

Ship, and the

Raven--Bennett's Hall, which

was

the

mint when Shrewsbury played

its part in the Civil

War, and last, but not

least,

the

house in Wyle Cop, one of the

finest in the town, where

Henry Earl of

Richmond

stayed on his way to Bosworth

field to win the English

Crown. Such are

some

of the beauties of old

Shrewsbury which happily

have not yet

vanished.

House

that the Earl of Richmond

stayed in before the Battle of

Bosworth,

Shrewsbury

Not

far removed from Shrewsbury

is Coventry, which at one time

could boast of a

city

wall and a castle. In the reign of

Richard II this wall was

built, strengthened by

towers.

Leland, writing in the time

of Henry VIII, states that

the city was begun

to

be

walled in when Edward II

reigned, and that it had six

gates, many fair

towers,

and

streets well built with

timber. Other writers speak

of thirty-two towers and

twelve

gates. But few traces of

these remain. The citizens

of Coventry took an

active

part in the Civil War in

favour of the Parliamentary

army, and when

Charles

II

came to the throne he ordered

these defences to be demolished.

The gates were

left,

but most of them have since

been destroyed. Coventry is a

city of fine old

timber-framed

fifteenth-century houses with

gables and carved barge-boards and

projecting

storeys, though many of them

are decayed and may not

last many years.

The

city has had a fortunate

immunity from serious fires. We

give an illustration of

one

of the old Coventry streets

called Spon Street, with its

picturesque houses.

These

old streets are numerous,

tortuous and irregular. One of

the richest and most

interesting

examples of domestic architecture in

England is St. Mary's Hall,

erected

in

the time of Henry VI. Its

origin is connected with

ancient guilds of the city,

and

in

it were stored their books and archives.

The grotesquely carved roof,

minstrels'

gallery,

armoury, state-chair, great painted

window, and a fine specimen of

fifteenth-century

tapestry are interesting

features of this famous

hall, which

furnishes

a vivid idea of the manners

and civic customs of the age

when Coventry

was

the favourite resort of

kings and princes. It has

several fine churches,

though

the

cathedral was levelled with

the ground by that

arch-destroyer Henry VIII.

Coventry

remains one of the most

interesting towns in

England.

One

other walled town we will

single out for especial

notice in this

chapter--the

quaint,

picturesque, peaceful, placid

town of Rye on the Sussex

coast. It was once

wooed

by the sea, which surrounded

the rocky island on which it

stands, but the

fickle

sea has retired and

left it lonely on its hill

with a long stretch of

marshland

between

it and the waves. This must

have taken place about the

fifteenth century.

Our

illustration of a disused mooring-post

(p. 24) is a symbol of the

departed

greatness

of the town as a naval

station. The River Rother

connects it with the

sea,

and

the few barges and humble

craft and a few small

shipbuilding yards remind

it

of

its palmy days when it was a

member of the Cinque Ports,

a rich and prosperous

town

that sent forth its ships to

fight the naval battles of

England and win

honour

for

Rye and St. George. During

the French wars English

vessels often visited

French

ports and towns along the

coast and burned and pillaged

them. The French

sailors

retaliated with equal zest,

and many of our southern

towns have suffered

from

fire and sword during those

adventurous days.

Old

Houses formerly standing in Spon Street

Coventry

Rye

was strongly fortified by a wall

with gates and towers

and a fosse, but the

defences

suffered grievously from the

attacks of the French, and the

folk of Rye

were

obliged to send a moving

petition to King Richard II,

praying him "to

have

consideration

of the poor town of Rye,

inasmuch as it had been

several times taken,

and

is unable further to repair

the walls, wherefore the

town is, on the

sea-side,

open

to enemies." I am afraid that

the King did not at once

grant their petition,

as

two

years later, in 1380, the

French came again and set

fire to the town. With

the

departure

of the sea and the

diminishing of the harbour,

the population

decreased

and

the prosperity of Rye

declined. Refugees from France have on

two notable

occasions

added to the number of its

inhabitants. After the

Massacre of St.

Bartholomew

seven hundred scared and frightened

Protestants arrived at Rye and

brought

with them their industry,

and later on, after the

Revocation of the Edict

of

Nantes,

many Huguenots settled here and

made it almost a French

town. We need

not

record all the royal

visits, the alarms of

attack, the plagues, and other

incidents

that

have diversified the life of

Rye. We will glance at the

relics that remain.

The

walls

seem never to have recovered

from the attack of the

French, but one gate

is

standing--the

Landgate on the north-east of the

town, built in 1360, and

consisting

of

a broad arch flanked by two massive

towers with chambers above for

archers

and

defenders. Formerly there were

two other gates, but

these have vanished

save

only

the sculptured arms of the

Cinque Ports that once adorned the

Strand Gate.

The

Ypres tower is a memorial of

the ancient strength of the

town, and was

originally

built by William de Ypres,

Earl of Kent, in the twelfth

century, but has

received

later additions. It has a

stern, gaunt appearance, and

until recent times

was

used

as a jail. The church

possesses many points of

unique interest. The

builders

began

in the twelfth century to

build the tower and transepts,

which are Norman;

then

they proceeded with the

nave, which is Transitional; and

when they reached

the

choir, which is very large

and fine, the style had

merged into the Early

English.

Later

windows were inserted in the

fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The church

has

suffered with the town at

the hands of the French

invaders, who did

much

damage.

The old clock, with

its huge swinging pendulum,

is curious. The

church

has

a collection of old books, including

some old Bibles, including a

Vinegar and a

Breeches

Bible, and some stone

cannon-balls, mementoes of the French

invasion of

1448.

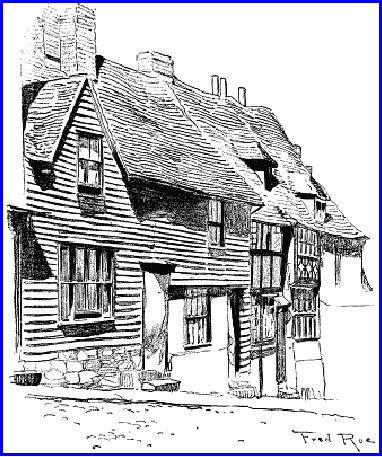

West

Street, Rye

Near

the church is the Town Hall,

which contains several

relics of olden days.

The

list

of mayors extends from the

time of Edward I, and we notice

the long

continuance

of the office in families.

Thus the Lambs held

office from 1723 to

1832,

and the Grebells from 1631 to

1741. A great tragedy happened in

the

churchyard.

A man named Breedes had a grudge against

one of the Lambs, and

intended

to kill him. He saw, as he

thought, his victim walking

along the dark

path

through

the shrubs in the

churchyard, attacked and murdered

him. But he had made

a

mistake; his victim was Mr.

Grebell. The murderer was

hanged and quartered.

The

Town Hall contains the

ancient pillory, which was

described as a very

handy

affair,

handcuffs, leg-irons, special constables' staves,

which were always

much

needed

for the usual riots on

Gunpowder Plot Day, and

the old primitive

fire-engine

dated

1745. The town has

some remarkable plate. There

is the mayor's

handbell

with

the inscription:--

O

MATER DEI

MEMENTO

MEI.

1566.

PETRUS

GHEINEUS

ME

FECIT.

The

maces of Queen Elizabeth

with the date 1570

and bearing the fleur-de-lis

and

the

Tudor rose are interesting,

and the two silver maces

presented by George III,

bearing

the arms of Rye and weighing 962

oz., are said to be the

finest in Europe.

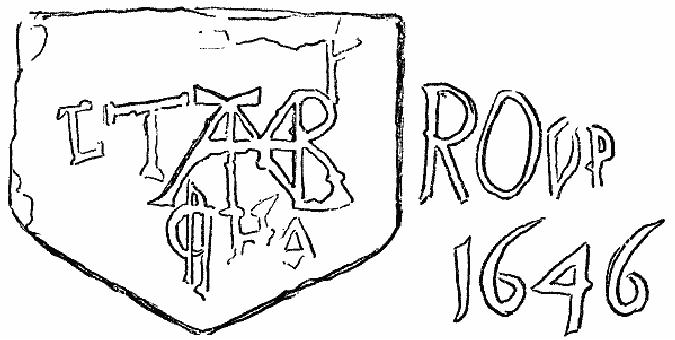

Monogram

and Inscription in the Mermaid

Inn, Rye

The

chief charm of Rye is to

walk along the narrow

streets and lanes, and see

the

picturesque

rows and groups of old

fifteenth-and sixteenth-century houses

with

their

tiled roofs and gables, weather-boarded

or tile-hung after the

manner of

Sussex

cottages, graceful bay-windows--altogether

pleasing. Wherever one

wanders

one meets with these

charming dwellings, especially in

West Street and

Pump

Street; the oldest house in

Rye being at the corner of

the churchyard. The

Mermaid

Inn is delightful both outside

and inside, with its

low panelled rooms,

immense

fire-places and dog-grates. We see the

monogram and names and

dates

carved

on the stone fire-places, 1643,

1646, the name Loffelholtz seeming

to

indicate

some foreign refugee or

settler. It is pleasant to find at least in one

town in

England

so much that has been

left unaltered and so little

spoilt.

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION