|

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND |

| << INTRODUCTION |

| OLD WALLED TOWNS >> |

CHAPTER

II

THE

DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

Under

this alarming heading, "The

Disappearance of England," the

Gaulois

recently

published an article by M. Guy Dorval on

the erosion of the

English

coasts.

The writer refers to the

predictions of certain British

men of science that

England

will one day disappear altogether beneath

the waves, and imagines

that we

British

folk are seized by a popular

panic. Our neighbours are

trembling for the

fate

of

the entente

cordiale, which

would speedily vanish with

vanishing England;

but

they

have been assured by some of

their savants that the rate of

erosion is only one

kilometre

in a thousand years, and that

the danger of total extinction is

somewhat

remote.

Professor Stanislas Meunier, however,

declares that our "panic" is

based on

scientific

facts. He tells us that the

cliffs of Brighton are now

one kilometre farther

away

from the French coast

than in the days of Queen

Elizabeth, and that those of

Kent

are six kilometres farther

away than in the Roman

period. He compares

our

island

to a large piece of sugar in water,

but we may rest assured that

before we

disappear

beneath the waves the period

which must elapse would be

greater than

the

longest civilizations known in

history. So we may hope to be able to

sing "Rule

Britannia"

for many a long

year.

Coast

erosion is, however, a serious

problem, and has caused the

destruction of

many

a fair town and noble forest

that now lie beneath the

seas, and the

crumbling

cliffs

on our eastern shore threaten to

destroy many a village

church and smiling

pasture.

Fishermen tell you that

when storms rage and the

waves swell they

have

heard

the bells chiming in the

towers long covered by the

seas, and nigh the

picturesque

village of Bosham we were

told of a stretch of sea

that was called the

Park.

This as late as the days of

Henry VIII was a favourite royal

hunting forest,

wherein

stags and fawns and does

disported themselves; now

fish are the only

prey

that

can be slain therein.

The

Royal Commission on coast

erosion relieves our minds

somewhat by assuring

us

that although the sea gains

upon the land in many

places, the land gains upon

the

sea

in others, and that the loss and

gain are more or less

balanced. As a matter of

area

this is true. Most of the

land that has been

rescued from the pitiless

sea is

below

high-water mark, and is protected by

artificial banks. This work

of

reclaiming

land can, of course, only be

accomplished in sheltered places,

for

example,

in the great flat bordering

the Wash, which flat is

formed by the deposit

of

the rivers of the Fenland,

and the seaward face of this

region is gradually

being

pushed

forward by the careful

processes of enclosure. You can see

the various old

sea

walls which have been

constructed from Roman times

onward. Some

accretions

of

land have occurred where

the sea piles up masses of

shingle, unless

foolish

people

cart away the shingle in

such quantities that the

waves again assert

themselves.

Sometimes sand silts up as at Southport

in Lancashire, where there

is

the

second longest pier in

England, a mile in length,

from the end of which it is

said

that

on a clear day with a

powerful telescope you may

perchance see the sea, that

a

distinguished

traveller accustomed to the deserts of

Sahara once found it, and

that

the

name Southport is altogether a misnomer,

as it is in the north and there is

no

port

at all.

But

however much as an Englishman I

might rejoice that the

actual area of "our

tight

little island," which after

all is not very tight,

should not be diminishing,

it

would

be a poor consolation to me, if I

possessed land and houses on

the coast of

Norfolk

which were fast slipping

into the sea, to know

that in the Fenland

industrious

farmers were adding to their

acres. And day by day,

year by year, this

destruction

is going on, and the gradual

melting away of land. The

attack is not

always

persistent. It is intermittent. Sometimes

the progress of the sea

seems to be

stayed,

and then a violent storm

arises and falling cliffs and submerged

houses

proclaim

the sway of the relentless

waves. We find that the

greatest loss has

occurred

on the east and southern

coasts of our island. Great

damage has been

wrought

all along the Yorkshire

sea-board from Bridlington to

Kilnsea, and the

following

districts have been the

greatest sufferers: between

Cromer and

Happisburgh,

Norfolk; between Pakefield

and Southwold, Suffolk;

Hampton and

Herne

Bay, and then St.

Margaret's Bay, near Dover;

the coast of Sussex, east

of

Brighton,

and the Isle of Wight; the

region of Bournemouth and Poole;

Lyme Bay,

Dorset,

and Bridgwater Bay, Somerset.

All

along the coast from

Yarmouth to Eastbourne, with a

few exceptional parts, we

find

that the sea is gaining on

the land by leaps and

bounds. It is a coast that is

most

favourably

constructed for coast

erosion. There are no hard

or firm rocks, no

cliffs

high

enough to give rise to a respectable

landslip; the soil is

composed of loose

sand

and gravels, loams and

clays, nothing to resist the assaults of

atmospheric

action

from above or the sea below.

At Covehithe, on the Suffolk

coast, there has

been

the greatest loss of land. In 1887

sixty feet was claimed by

the sea, and in

ten

years

(1878-87) the loss was at

the rate of over eighteen

feet a year. In 1895

another

heavy loss occurred between

Southwold and Covehithe and a new

cove

formed.

Easton Bavent has entirely

disappeared, and so have the once

prosperous

villages

of Covehithe, Burgh-next-Walton, and

Newton-by-Corton, and the

same

fate

seems to be awaiting Pakefield,

Southwold, and other

coast-lying towns.

Easton

Bavent once had such a flourishing

fishery that it paid an annual

rent of

3110

herrings; and millions of herrings

must have been caught by

the fishermen of

disappeared

Dunwich, which we shall

visit presently, as they paid

annually "fish-

fare"

to the clergy of the town

15,377 herrings, besides 70,000 to

the royal treasury.

The

summer visitors to the pleasant

watering-place Felixstowe, named after

St.

Felix,

who converted the East

Anglians to Christianity and was their

first bishop,

that

being the place where the

monks of the priory of St.

Felix in Walton held

their

annual

fair, seldom reflect that

the old Saxon burgh

was carried away as long

ago

as

1100 A.D. Hence Earl

Bigot was compelled to retire

inland and erect his

famous

castle

at Walton. But the sea

respected not the proud

walls of the baron's

stronghold;

the strong masonry that

girt the keep lies beneath

the waves; a heap of

stones,

called by the rustics Stone

Works, alone marks the site

of this once

powerful

castle. Two centuries later the baron's

marsh was destroyed by the

sea,

and

eighty acres of land was

lost, much to the regret of

the monks, who were

thus

deprived

of the rent and tithe

corn.

The

old chroniclers record many

dread visitations of the

relentless foe. Thus

in

1237

we read: "The sea burst with

high tides and tempests of winds,

marsh

countries

near the sea were flooded,

herds and flocks perished, and no

small

number

of men were lost and

drowned. The sea rose

continually for two days

and

one

night." Again in 1251: "On

Christmas night there was a

great thunder and

lightning

in Suffolk; the sea caused

heavy floods." In much later

times Defoe

records:

"Aldeburgh has two streets,

each near a mile long, but

its breadth, which

was

more considerable formerly, is not

proportionable, and the sea

has of late years

swallowed

up one whole street." It has

still standing close to the shore

its quaint

picturesque

town hall, erected in the

fifteenth century. Southwold is

now practically

an

island, bounded on the east

by the sea, on the

south-west by the Blyth

River, on

the

north-west by Buss Creek. It is only

joined to the mainland by a

narrow neck of

shingle

that divides Buss Creek from

the sea. I think that I

should prefer to hold

property

in a more secure region. You

invest your savings in

stock, and dividends

decrease

and your capital grows

smaller, but you usually

have something left.

But

when

your land and houses

vanish entirely beneath the

waves, the chapter is

ended

and

you have no further remedy

except to sue Father

Neptune, who has rather

a

wide

beat and may be difficult to

find when he is wanted to be served

with a

summons.

But

the Suffolk coast does

not show all loss. In

the north much land

has been

gained

in the region of Beccles, which was at

one time close to the sea, and one

of

the

finest spreads of shingle in

England extends from

Aideburgh to Bawdry.

This

shingle

has silted up many a Suffolk

port, but it has proved a

very effectual

barrier

against

the inroads of the sea.

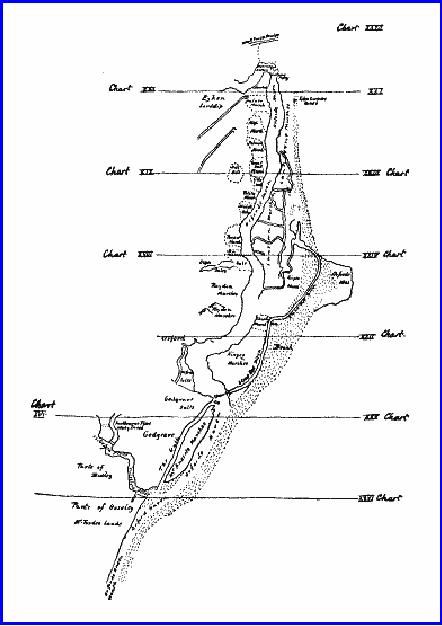

Norden's map of the coast

made in 16012

shows

this

wonderful

mass of shingle, which has

greatly increased since Norden's

day. It has

been

growing in a southerly direction,

until the Aide River had

until recently an

estuary

ten miles in length. But in

1907 the sea asserted

itself, and "burst

through

the

stony barrier, making a

passage for the exit of

the river one mile further

north,

and

leaving a vast stretch of

shingle and two deserted

river-channels as a protection

to

the Marshes of Hollesley

from further inroads of the

sea."3

Formerly

the River

Alde

flowed direct to the sea

just south of the town of

Aldeburgh. Perhaps

some

day

it may be able to again force a passage

near its ancient course or by

Havergate

Island.

This alteration in the course of

rivers is very remarkable, and

may be

observed

at Christ Church,

Hants.

It

is pathetic to think of the

historic churches, beautiful

villages, and smiling

pastures

that have been swept

away by the relentless sea.

There are no less

than

twelve

towns and villages in Yorkshire

that have been thus

buried, and five in

Suffolk.

Ravensburgh, in the former

county, was once a flourishing seaport.

Here

landed

Henry IV in 1399, and Edward IV in

1471. It returned two members

to

Parliament.

An old picture of the place

shows the church, a large

cross, and houses;

but

it has vanished with the

neighbouring villages of Redmare,

Tharlethorp,

Frismarch,

and Potterfleet, and "left not a

wrack behind." Leland

mentions it in

1538,

after which time its place

in history and on the map knows it no

more. The

ancient

church of Kilnsea lost half

its fabric in 1826, and the

rest followed in 1831.

Alborough

Church and the Castle of Grimston

have entirely vanished.

Mapleton

Church

was formerly two miles from

the sea; it is now on a

cliff with the sea at

its

feet,

awaiting the final attack of

the all-devouring enemy.

Nearly a century ago

Owthorne

Church and churchyard were

overwhelmed, and the shore was

strewn

with

ruins and shattered coffins. On the

Tyneside the destruction has

been

remarkable

and rapid. In the district of

Saltworks there was a house built

standing

on

the cliff, but it was never

finished, and fell a prey to

the waves. At Percy

Square

an

inn and two cottages

have been destroyed. The

edge of the cliff in 1827

was

eighty

feet seaward, and the banks of Percy

Square receded a hundred and

eighty

feet

between the years 1827 and

1892. Altogether four acres

have disappeared. An

old

Roman building, locally

known as "Gingling Geordie's Hole," and

large masses

of

the Castle Cliff fell into

the sea in the 'eighties.

The remains of the

once

flourishing

town of Seaton, on the Durham coast,

can be discovered amid the

sands

at

low tide. The modern

village has sunk inland, and

cannot now boast of

an

ancient

chapel dedicated to St.

Thomas of Canterbury, which

has been devoured by

the

waves.

Skegness,

on the Lincolnshire coast, was a large

and important town; it boasted of

a

castle

with strong fortifications and a

church with a lofty spire;

it now lies deep

beneath

the devouring sea, which no

guarding walls could

conquer. Far out at

sea,

beneath

the waves, lies old

Cromer Church, and when

storms rage its bells

are said

to

chime. The churchyard

wherein was written the

pathetic ballad "The Garden

of

Sleep"

is gradually disappearing, and "the graves of

the fair women that

sleep by

the

cliffs by the sea" have

been outraged, and their

bodies scattered and

devoured

by

the pitiless waves.

One

of the greatest prizes of

the sea is the ancient

city of Dunwich, which

dates

back

to the Roman era. The

Domesday Survey shows that

it was then a

considerable

town having 236 burgesses. It was

girt with strong walls; it

possessed

an

episcopal palace, the seat of

the East Anglian bishopric;

it had (so Stow

asserts)

fifty-two

churches, a monastery, brazen

gates, a town hall,

hospitals, and the

dignity

of possessing a mint. Stow

tells of its departed

glories, its royal

and

episcopal

palaces, the sumptuous

mansion of the mayor, its

numerous churches and

its

windmills, its harbour

crowded with shipping, which

sent forth forty vessels

for

the

king's service in the

thirteenth century. Though

Dunwich was an important

place,

Stow's description of it is rather

exaggerated. It could never have had

more

than

ten churches and monasteries. Its

"brazen gates" are mythical,

though it had its

Lepers'

Gate, South Gate, and others. It was once

a thriving city of

wealthy

merchants

and industrious fishermen. King

John granted to it a charter. It

suffered

from

the attacks of armed men as well as

from the ravages of the

sea. Earl Bigot

and

the revolting barons besieged it in

the reign of Edward I. Its

decay was gradual.

In

1342, in the parish of St.

Nicholas, out of three

hundred houses only

eighteen

remained.

Only seven out of a hundred

houses were standing in the

parish of St.

Martin.

St. Peter's parish was

devastated and depopulated. It had a

small round

church,

like that at Cambridge,

called the Temple, once the

property of the

Knights

Templars,

richly endowed with costly

gifts. This was a place of sanctuary, as

were

the

other churches in the city.

With the destruction of the

houses came also the

decay

of the port which no ships

could enter. Its rival,

Southwold, attracted

the

vessels

of strangers. The markets and fairs

were deserted. Silence and

ruin reigned

over

the doomed town, and the

ruined church of All Saints is all

that remains of its

former

glories, save what the

storms sometimes toss along

the beach for the

study

and

edification of antiquaries.

As

we proceed down the coast we

find that the sea is

still gaining on the land.

The

old

church at Walton-on-the-Naze was swept

away, and is replaced by a new

one.

A

flourishing town existed at

Reculver, which dates back to

the Romans. It was a

prosperous

place, and had a noble church,

which in the sixteenth

century was a mile

from

the sea. Steadily have

the waves advanced, until a

century ago the church

fell

into

the sea, save two

towers which have been

preserved by means of elaborate

sea-

walls

as a landmark for

sailors.

The

fickle sea has deserted

some towns and destroyed

their prosperity; it

has

receded

all along the coast

from Folkestone to the

Sussex border, and left some

of

the

famous Cinque Ports, some of

which we shall visit again,

Lymne, Romney,

Hythe,

Richborough, Stonor, Sandwich, and

Sarre high and dry,

with little or no

access

to the sea. Winchelsea has

had a strange career. The old town

lies beneath

the

waves, but a new Winchelsea

arose, once a flourishing port,

but now deserted

and

forlorn with the sea a

mile away. Rye, too,

has been forsaken. It was once

an

island;

now the little Rother stream

conveys small vessels to the

sea, which looks

very

far away.

We

cannot follow all the

victories of the sea. We

might examine the inroads

made

by

the waves at Selsea. There

stood the first cathedral of

the district before

Chichester

was founded. The building is

now beneath the sea, and since

Saxon

times

half of the Selsea Bill has

vanished. The village of

Selsea rested securely

in

the

centre of the peninsula, but

only half a mile now

separates it from the sea.

Some

land

has been gained near this

projecting headland by an industrious

farmer. His

farm

surrounded a large cove with

a narrow mouth through which

the sea poured. If

he

could only dam up that

entrance, he thought he could

rescue the bed of the

cove

and

add to his acres. He bought

an old ship and sank it by the

entrance and

proceeded

to drain. But a tiresome

storm arose and drove

the ship right across

the

cove,

and the sea poured in again. By no

means discouraged, he dammed up

the

entrance

more effectually, got rid of

the water, increased his

farm by many acres,

and

the old ship makes an

admirable cow-shed.

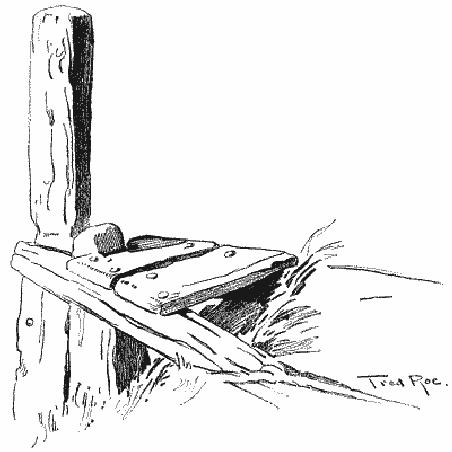

Disused

Mooring-Post on bank of the

Rother, Rye

The

Isle of Wight in remote

geological periods was part of the

mainland. The Scilly

Isles

were once joined with

Cornwall, and were not

severed until the

fourteenth

century,

when by a mighty storm and

flood, 140 churches and villages

were

destroyed

and overwhelmed, and 190 square

miles of land carried away.

Much land

has

been lost in the Wirral

district of Cheshire. Great

forests have been

overwhelmed,

as the skulls and bones of

deer and horse and fresh-water

shell-fish

have

been frequently discovered at low

tide. Fifty years ago a distance of

half a

mile

separated Leasowes Castle from

the sea; now its

walls are washed by

the

waves.

The Pennystone, off the

Lancashire coast by Blackpool,

tells of a

submerged

village and manor, about

which cluster romantic

legends.

Such

is the sad record of the

sea's destruction, for which

the industrious

reclamation

of land, the compensations wrought by

the accumulation of shingle

and

sand

dunes and the silting of estuaries can

scarcely compensate us. How

does the

sea

work this? There are

certain rock-boring animals,

such as the Pholas,

which

help

to decay the rocks. Each mollusc

cuts a series of augur-holes

from two to four

inches

deep, and so assists in destroying

the bulwarks of England.

Atmospheric

action,

the disintegration of soft

rocks by frost and by the

attack of the sea

below,

all

tend in the same direction.

But the foolish action of

man in removing

shingle,

the

natural protection of our

coasts, is also very mischievous.

There is an instance

of

this in the Hall Sands and

Bee Sands, Devon. A company

a few years ago

obtained

authority to dredge both

from the foreshore and

sea-bed. The

Commissioners

of Woods and Forests and the

Board of Trade granted

this

permission,

the latter receiving a

royalty of �50 and the former

�150. This occurred

in

1896. Soon afterwards a heavy gale

arose and caused an immense

amount of

damage,

the result entirely of this

dredging. The company had to

pay heavily, and

the

royalties were returned to

them. This is only one

instance out of many

which

might

be quoted. We are an illogical

nation, and our regulations and

authorities are

weirdly

confused. It appears that

the foreshore is under the

control of the Board

of

Trade,

and then a narrow strip of

land is ruled over by the

Commissioners of

Woods

and Forests. Of course these bodies do

not agree; different

policies are

pursued

by each, and the coast

suffers. Large sums are sometimes spent

in coast-

defence

works. At Spurn no less than

�37,433 has been spent out

of Parliamentary

grants,

besides �14,227 out of the

Mercantile Marine Fund.

Corporations or county

authorities,

finding their coasts being

worn away, resolve to

protect it. They

obtain

a

grant in aid from Parliament,

spend vast sums, and often

find their work

entirely

thrown

away, or proving itself most

disastrous to their neighbours. If you

protect

one

part of the coast you

destroy another. Such is the

rule of the sea. If you

try to

beat

it back at one point it will revenge

itself on another. If only

you can cause

shingle

to accumulate before your threatened

town or homestead, you know

you

can

make the place safe and

secure from the waves.

But if you stop this flow

of

shingle

you may protect your

own homes, but you deprive

your neighbours of

this

safeguard

against the ravages of the

sea. It was so at Deal. The

good folks of Deal

placed

groynes in order to stop the

flow of shingle and protect

the town. They

did

their

duty well; they stopped

the shingle and made a good

bulwark against the

sea.

With

what result? In a few years'

time they caused the

destruction of Sandown,

which

had been deprived of its

natural protection. Mr. W. Whitaker,

F.R.S., who

has

walked along the whole

coast from Norfolk to

Cornwall, besides visiting

other

parts

of our English shore, and

whose contributions to the

Report of the Royal

Commission

on Coast Erosion are so

valuable, remembers when a boy

the Castle of

Sandown,

which dated from the

time of Henry VIII. It was then in a

sound

condition

and was inhabited. Now it is

destroyed, and the batteries farther

north

have

gone too. The same thing is

going on at Dover. The

Admiralty Pier causes

the

accumulation

of shingle on its west side,

and prevents it from following

its natural

course

in a north-easterly direction. Hence

the base of the cliffs on

the other side of

the

pier and harbour is left

bare and unprotected; this

aids erosion, and not

unfrequently

do we hear of the fall of the

chalk cliffs.

Isolated

schemes for the prevention

of coast erosion are of

little avail. They can

do

no

good, and only increase the

waste and destruction of land in

neighbouring

shores.

Stringent laws should be

passed to prevent the taking

away of shingle from

protecting

beaches, and to prohibit the

ploughing of land near the

edge of cliffs,

which

greatly assists atmospheric

destructive action from

above. The State

has

recently

threatened the abandonment of

the coastguard service. This

would be a

disastrous

policy. Though the primary

object of coastguards, the prevention

of

smuggling,

has almost passed away,

the old sailors who

act as guardians of

our

coast-line

render valuable services to the

country. They are most

useful in looking

after

the foreshore. They save

many lives from wrecked

vessels, and keep watch

and

ward to guard our shores,

and give timely notice of

the advance of a hostile

fleet,

or of that ever-present foe

which, though it affords

some protection for

our

island

home from armed invasion,

does not fail to exact a

heavy tithe from the

land

it

guards, and has destroyed so many once

flourishing towns and villages by

its

ceaseless

attack.

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION