|

OLD BRIDGES |

| << STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS |

| OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES >> |

CHAPTER

XIV

OLD

BRIDGES

The

passing away of the old

bridges is a deplorable feature of

vanishing England.

Since

the introduction of those terrible

traction-engines, monstrous machines

that

drag

behind them a whole train of

heavily laden trucks, few of

these old structures

that

have survived centuries of

ordinary use are safe

from destruction. The

immense

weight of these road-trains

are enough to break the back of

any of the old-

fashioned

bridges. Constantly notices have to be

set up stating: "This bridge

is only

sufficient

to carry the ordinary

traffic of the district, and

traction-engines are

not

allowed

to proceed over it." Then

comes an outcry from the

proprietors of

locomotives

demanding bridges suitable for

their convenience. County

councils and

district

councils are worried by

their importunities, and soon

the venerable

structures

are doomed, and an iron-girder

bridge hideous in every

particular

replaces

one of the most beautiful

features of our

village.

When

the Sonning bridges that

span the Thames were

threatened a few years ago,

English

artists, such as Mr. Leslie and Mr.

Holman-Hunt, strove manfully

for their

defence.

The latter wrote:--

"The

nation, without doubt, is in serious

danger of losing faith in

the

testimony

of our poets and painters to

the exceptional beauty of

the

land

which has inspired them.

The poets, from Chaucer to

the last of

his

true British successors,

with one voice enlarge on

the overflowing

sweetness

of England, her hills and

dales, her pastures with

sweet

flowers,

and the loveliness of her

silver streams. It is the cherishing

of

the

wholesome enjoyments of daily

life that has implanted in

the sons

of

England love of home,

goodness of nature, and

sweet

reasonableness,

and has given strength to

the thews and sinews of

her

children,

enabling them to defend her

land, her principles, and

her

prosperity.

With regard to the three

Sonning bridges, parts of them

have

been already rebuilt with

iron fittings in recent

years, and no

disinterested

reasonable person can see why they could

not be easily

made

sufficient to carry all

existing traffic. If the bridges

were to be

widened

in the service of some

disproportionate vehicles it is

obvious

that

the traffic such enlarged

bridges are intended to carry

would be put

forward

as an argument for demolishing

the exquisite old bridge

over

the

main river which is the

glory of this exceptionally

picturesque and

well-ordered

village; and this is a

matter of which even the

most

utilitarian

would soon see the evil in

the diminished attraction of

the

river

not only to Englishmen, but

to Colonials and Americans

who

have

across the sea read

widely of its beauty. Remonstrances

must look

ahead,

and can only now be of avail

in recognition of future

further

danger.

We are called upon to plead

the cause for the

whole of the

beauty-loving

England, and of all river-loving people

in particular."

Gallantly

does the great painter

express the views of

artists, and such vandalism

is

as

obnoxious to antiquaries as it is to

artists and lovers of the

picturesque. Many of

these

old bridges date from

medieval times, and are

relics of antiquity that can ill

be

spared.

Brick is a material as nearly

imperishable as any that man

can build with.

There

is hardly any limit to the

life of a brick or stone bridge, whereas

an iron or

steel

bridge requires constant

supervision. The oldest iron

bridge in this

country--

at

Coalbrookdale, in Shropshire--has failed

after 123 years of life. It was

worn out

by

old age, whereas the Roman

bridge at Rimini, and the

medieval ones at St.

Ives,

Bradford-on-Avon,

and countless other places in

this country and abroad, are

in

daily

use and are likely to

remain serviceable for many

years to come, unless these

ponderous

trains break them

down.

The

interesting bridge which

crosses the River Conway at

Llanrwst was built in

1636

by Sir Richard Wynn, then

the owner of Gwydir Castle,

from the designs of

Inigo

Jones. Like many others, it

is being injured by traction-trains

carrying

unlimited

weights. Happily the Society

for the Protection of

Ancient Buildings

heard

the plaint of the old

bridge that groaned under

its heavy burdens and

cried

aloud

for pity. The society

listened to its pleading, and

carried its petition to

the

Carmarthen

County Council, with

excellent results. This

enlightened Council

decided

to protect the bridge and

save it from further

harm.

The

building of bridges was anciently

regarded as a charitable and

religious act,

and

guilds and brotherhoods existed

for their maintenance and

reparation. At

Maidenhead

there was a notable bridge,

for the sustenance of which

the Guild of St.

Andrew

and St. Mary Magdalene was

established by Henry VI in 1452. An

early

bridge

existed here in the thirteenth

century, a grant having been

made in 1298 for

its

repair. A bridge-master was one of the

officials of the corporation,

according to

the

charter granted to the town

by James II. The old bridge

was built of wood and

supported

by piles. No wonder that people

were terrified at the

thought of passing

over

such structures in dark

nights and stormy weather.

There was often a

bridge-

chapel,

as on the old Caversham

bridge, wherein they said

their prayers, and

perhaps

made their wills, before

they ventured to

cross.

Some

towns owe their existence to

the making of bridges. It

was so at Maidenhead.

It

was quite a small place, a

cluster of cottages, but Camden tells us

that after the

erection

of the bridge the town

began to have inns and to be so

frequented as to

outvie

its "neighbouring mother,

Bray, a much more ancient

place," where the

famous

"Vicar" lived. The old

bridge gave place in 1772 to a grand new

one with

very

graceful arches, which was

designed by Sir Roland

Taylor.

Abingdon,

another of our Berkshire

towns, has a famous bridge

that dates back to

the

fifteenth century, when it

was erected by some good

merchants of the

town,

John

Brett and John Huchyns and

Geoffrey Barbour, with the

aid of Sir Peter

Besils

of

Besselsleigh, who supplied

the stone from his quarries.

It is an extremely

graceful

structure, well worthy of

the skill of the medieval

builders. It is some

hundreds

of yards in length, spanning

the Thames and meadows that

are often

flooded,

the main stream being

spanned by six arches. Henry V is

credited with its

construction,

but he only graciously bestowed

his royal licence. In fact

these

merchants

built two bridges, one called

Burford Bridge and the other

across the

ford

at Culham. The name Burford

has nothing to do with the

beautiful old town

which

we have already visited, but

is a corruption of Borough-ford, the

town ford at

Abingdon.

Two poets have sung their

praises, one in atrocious Latin and

the other

in

quaint, old-fashioned English.

The first poet made a bad

shot at the name of

the

king,

calling him Henry IV instead of

Henry V, though it is a matter of

little

importance,

as neither monarch had anything to do

with founding the structure.

The

Latin

poet sings, if we may call it

singing:--

Henricus

Quartus quarto fundaverat

anno

Rex

pontem Burford super undas atque

Culham-ford.

The

English poet fixes the date

of the bridge, 4 Henry V

(1416) and thus tells

its

story:--

King

Henry the fyft, in his

fourthe yere

He

hath i-founde for his

folke a brige in

Berkshire

For

cartis with cariage may goo

and come clere,

That

many wynters afore were

marred in the myre.

Now

is Culham hithe57

i-come to

an ende

And

al the contre the better and

no man the worse,

Few

folke there were coude that

way mende,

But

they waged a cold or payed of ther

purse;

An

if it were a beggar had breed in

his bagge,

He

schulde be right soone i-bid

to goo aboute;

And

if the pore penyless the

hireward would have,

A

hood or a girdle and let him

goo aboute.

Culham

hithe hath caused many a

curse

I'

blyssed be our helpers we

have a better waye,

Without

any peny for cart and

horse.

Another

blyssed besiness is brigges to

make

That

there the pepul may

not passe after great

schowres,

Dole

it is to draw a dead body

out of a lake

That

was fulled in a fount stoon

and felow of owres.

The

poet was grateful for the mercies

conveyed to him by the

bridge. "Fulled in a

fount

stoon," of course, means "washed or

baptized in a stone font." He reveals

the

misery

and danger of passing through a ford

"after great showers," and the

sad

deaths

which befell adventurous

passengers when the river

was swollen by rains

and

the ford well-nigh impassable. No

wonder the builders of bridges

earned the

gratitude

of their fellows. Moreover,

this Abingdon Bridge was

free to all persons,

rich

and poor alike, and no toll or pontage

was demanded from those who

would

cross

it.

Within

the memory of man there was

a beautiful old bridge

between Reading and

Caversham.

It was built of brick, and had ten

arches, some constructed of

stone.

About

the time of the Restoration

some of these were ruinous,

and obstructed the

passage

by penning up the water above

the bridge so that boats

could not pass

without

the use of a winch, and in

the time of James II the

barge-masters of Oxford

appealed

to Courts of Exchequer, asserting that

the charges of pontage exacted on

all

barges passing under the

bridge were unlawful,

claiming exemption from

all

tolls

by reason of a charter granted to

the citizens of Oxford by

Richard II. They

won

their case. This bridge is

mentioned in the Close Rolls of

the early years of

Edward

I as a place where assizes were

held. The bridge at Cromarsh

and

Grandpont

outside Oxford were

frequently used for the

same purpose. So

narrow

was

it that two vehicles could

not pass. For the

safety of the foot passenger

little

angles

were provided at intervals

into which he could step in

order to avoid being

run

over by carts or coaches. The

chapel on the bridge was a

noted feature of the

bridge.

It was very ancient. In 1239 Engelard de

Cyngny was ordered to let

William,

chaplain of the chapel of

Caversham, have an oak out of

Windsor Forest

with

which to make shingles for

the roofing of the chapel.

Passengers made

offerings

in the chapel to the priest

in charge of it for the repair of

the bridge and

the

maintenance of the chapel and

priest. It contained many

relics of saints, which

at

the Dissolution were eagerly

seized by Dr. London, the

King's Commissioner.

About

the year 1870 the old

bridge was pulled down

and the present hideous

iron-

girder

erection substituted for it.

It is extremely ugly, but is

certainly more

convenient

than the old narrow

bridge, which required

passengers to retire into

the

angle

to avoid the danger of being

run over.

These

bridges can tell many tales of battle and

bloodshed. There was a

great

skirmish

on Caversham Bridge in the

Civil War in a vain attempt

on the part of the

Royalists

to relieve the siege of

Reading. When Wallingford was threatened

in the

same

period of the Great

Rebellion, one part of the

bridge was cut in order

to

prevent

the enemy riding into

the town. And you

can still detect the part

that was

severed.

There is a very interesting

old bridge across the

upper Thames between

Bampton

and Faringdon. It is called Radcot

Bridge; probably built in

the thirteenth

century,

with its three arches and a

heavy buttress in the middle

niched for a figure

of

the Virgin, and a cross

formerly stood in the centre. A

"cut" has diverted

the

course

of the river to another

channel, but the bridge

remains, and on this bridge

a

sharp

skirmish took place between

Robert de Vere, Earl of

Oxford, Marquis of

Dublin,

and Duke of Ireland, a favourite of

Richard II, upon whom the

King

delighted

to bestow titles and honours.

The rebellious lords met

the favourite's

forces

at Radcot, where a fierce

fight ensued. De Vere was taken in

the rear, and

surrounded

by the forces of the Duke of

Gloucester and the Earl of

Derby, and

being

hard pressed, he plunged

into the icy river

(it was on the 20th day

of

December,

1387) with his armour

on, and swimming down-stream

with difficulty

saved

his life. Of this exploit a

poet sings:--

Here

Oxford's hero, famous for

his boar,

While

clashing swords upon his

target sound,

And

showers of arrows from his

breast rebound,

Prepared

for worst of fates, undaunted

stood,

And

urged his heart into

the rapid flood.

The

waves in triumph bore him, and

were proud

To

sink beneath their honourable

load.

Religious

communities, monasteries and priories,

often constructed bridges.

There

is

a very curious one at Croyland,

probably erected by one of the

abbots of the

famous

abbey of Croyland or Crowland. This

bridge is regarded as one of

the

greatest

curiosities in the kingdom. It is

triangular in shape, and has

been supposed

to

be emblematical of the Trinity.

The rivers Welland, Nene,

and a drain called

Catwater

flow under it. The

ascent is very steep, so

that carriages go under it.

The

triangular

bridge of Croyland is mentioned in a

charter of King Edred about

the

year

941, but the present bridge

is probably not earlier than

the fourteenth

century.

However,

there is a rude statue said to be

that of King Ethelbald, and

may have

been

taken from the earlier

structure and built into the

present bridge. It is in a

sitting

posture at the end of the

south-west wall of the

bridge. The figure has

a

crown

on the head, behind which

are two wings, the arms

bound together, round

the

shoulders a kind of mantle, in

the left hand a sceptre and

in the right a globe.

The

bridge consists of three piers, whence

spring three pointed arches

which unite

their

groins in the centre.

Croyland is an instance of a decayed

town, the tide of

its

prosperity

having flowed elsewhere.

Though nominally a market-town, it is

only a

village,

with little more than

the ruins of its former

splendour remaining, when

the

great

abbey attracted to it crowds of the

nobles and gentry of England,

and

employed

vast numbers of labourers, masons, and

craftsmen on the works of

the

abbey

and in the supply of its

needs.

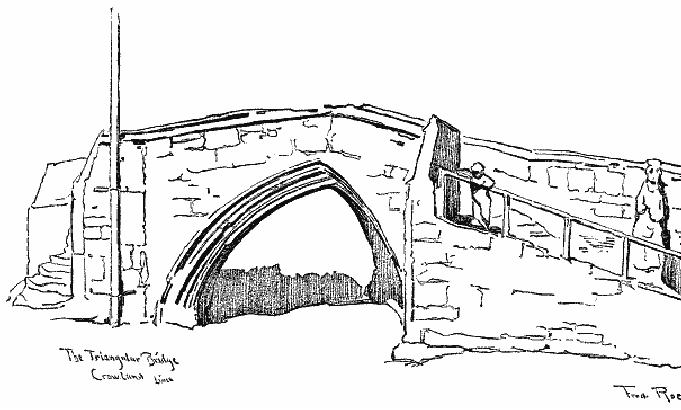

The

Triangular Bridge

Crowland

All

over the country we find

beautiful old bridges, though

the opening years of

the

present

century, with the increase

of heavy traction-engines, have

seen many

disappear.

At Coleshill, Warwickshire, there is a

graceful old bridge leading

to the

town

with its six arches and

massive cutwaters. Kent is a county of

bridges,

picturesque

medieval structures which

have survived the lapse of

time and the

storms

and floods of centuries. You can find

several of these that span

the Medway

far

from the busy railway

lines and the great roads.

There is a fine

medieval

fifteenth-century

bridge at Yalding across the

Beult, long, fairly level,

with deeply

embayed

cutwaters of rough ragstone. Twyford

Bridge belongs to the same

period,

and

Lodingford Bridge, with its

two arches and single-buttressed

cutwater, is very

picturesque.

Teston Bridge across the

Medway has five arches of

carefully wrought

stonework

and belongs to the fifteenth

century, and East Farleigh is a

fine example

of

the same period with

four ribbed and pointed

arches and four bold

cutwaters of

wrought

stones, one of the best in the

country. Aylesford Bridge is a

very graceful

structure,

though it has been altered

by the insertion of a wide

span arch in the

centre

for the improvement of river

navigation. Its existence

has been long

threatened,

and the Society for the

Protection of Ancient Buildings

has done its

utmost

to save the bridge from

destruction. Its efforts are

at length crowned

with

success,

and the Kent County Council

has decided that there

are not sufficient

grounds

to justify the demolition of

the bridge and that it shall

remain. The attack

upon

this venerable structure will

probably be renewed some

day, and its

friends

will

watch over it carefully and be

prepared to defend it again when

the next

onslaught

is made. It is certainly one of the

most beautiful bridges in Kent.

Little

known

and seldom seen by the

world, and unappreciated even by the

antiquary or

the

motorist, these Medway bridges

continue their placid existence and

proclaim

the

enduring work of the English

masons of nearly five

centuries ago.

Many

of our bridges are of great antiquity.

The Eashing bridges over the

Wey near

Godalming

date from the time of

King John and are of

singular charm and

beauty.

Like

many others they have

been threatened, the Rural

District Council

having

proposed

to widen and strengthen them, and

completely to alter their

character and

picturesqueness.

Happily the bridges were

private property, and by the

action of the

Old

Guildford Society and the

National Trust they have

been placed under the

guardianship

of the Trust, and are now

secure from

molestation.

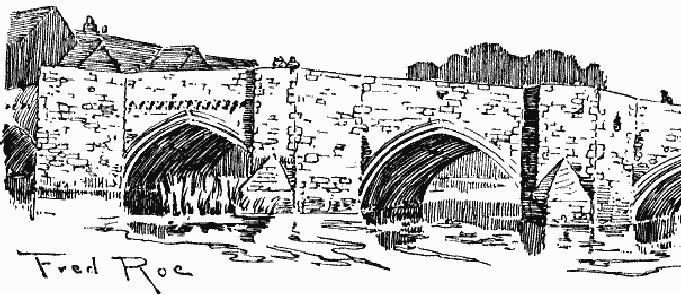

Huntingdon

Bridge

We

give an illustration of the Crane

Bridge, Salisbury, a small

Gothic bridge near

the

Church House, and seen in

conjunction with that

venerable building it forms

a

very

beautiful object. Another

illustration shows the huge

bridge at Huntingdon

spanning

the Ouse with six arches. It

is in good preservation, and has an

arcade of

Early

Gothic arches, and over it the

coaches used to run along

the great North

Road,

the scene of the mythical

ride of Dick Turpin, and

doubtless the youthful

feet

of

Oliver Cromwell, who was

born at Huntingdon, often

traversed it. There

is

another

fine bridge at St. Neots

with a watch-tower in the

centre.

The

little town of Bradford-on-Avon

has managed to preserve almost

more than

any

other place in England the

old features which are fast

vanishing elsewhere. We

have

already seen that most

interesting untouched specimen of Saxon

architecture

the

little Saxon church, which

we should like to think is

the actual church built

by

St.

Aldhelm, but we are

compelled to believe on the

authority of experts that it

is

not

earlier than the tenth

century. In all probability a

church was built by

St.

Aldhelm

at Bradford, probably of wood,

and was afterwards rebuilt

in stone when

the

land had rest and the raids of

the Danes had ceased, and

King Canute ruled and

encouraged

the building of churches,

and Bishops Dunstan and

�thelwold of

Winchester

were specially prominent in

the work. Bradford, too,

has its noble

church,

parts of which date back to Norman

times; its famous

fourteenth-century

barn

at Barton Farm, which has a

fifteenth-century porch and gatehouse;

many fine

examples

of the humbler specimens of

domestic architecture; and the

very

interesting

Kingston House of the

seventeenth century, built by one of

the rich

clothiers

of Bradford, when the little

town (like Abingdon)

"stondeth by clothing,"

and

all the houses in the place

were figuratively "built

upon wool-packs." But

we

are

thinking of bridges, and Bradford has

two, the earlier one being a

little

footbridge

by the abbey grange, now called

Barton Farm. Miss Alice

Dryden tells

the

story of the town bridge in

her Memorials

of Old Wiltshire. It was

originally

only

wide enough for a string of

packhorses to pass along it.

The ribbed portions

of

the

southernmost arches and the piers

for the chapel are

early fourteenth

century,

the

other arches were built

later. Bradford became so prosperous,

and the stream of

traffic

so much increased, and wains took

the place of packhorses, that the

narrow

bridge

was not sufficient for

it; so the good clothiers

built in the time of James I

a

second

bridge alongside the first.

Orders were issued in 1617 and 1621

for "the

repair

of the very fair bridge

consisting of many goodly

arches of freestone,"

which

had

fallen into decay. The cost

of repairing it was estimated at 200 marks.

There is

a

building on the bridge

corbelled out on a specially

built pier of the bridge,

the use

of

which is not at first sight

evident. Some people call it

the watch-house, and it

has

been

used as a lock-up; but Miss

Dryden tells us that it was

a chapel, similar to

those

which we have seen on many

other medieval bridges. It belonged to

the

Hospital

of St. Margaret, which stood at

the southern end of the

bridge, where the

Great

Western Railway crosses the

road. This chapel retains

little of its

original

work,

and was rebuilt when the

bridge was widened in the

time of James I.

Formerly

there was a niche for a

figure looking up the stream,

but this has gone

with

much else during the

drastic restoration. That a

bridge-chapel existed here is

proved

by Aubrey, who mentions "the

chapel for masse in the

middest of the

bridge"

at Bradford.

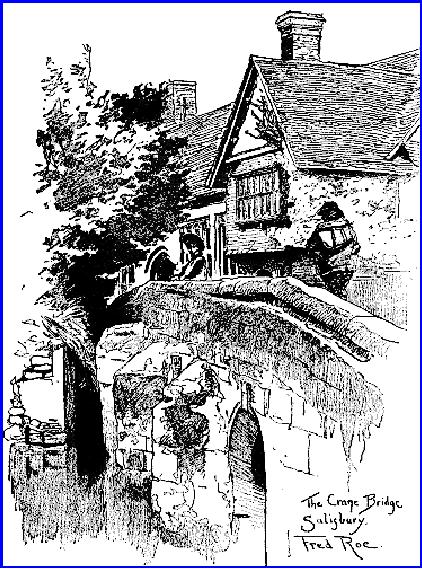

The

Crane Bridge, Salisbury

Sometimes

bridges owe their origin to

curious circumstances. There was an

old

bridge

at Olney, Buckinghamshire, of which

Cowper wrote when he

sang:--

That

with its wearisome but

needful length

Bestrides

the flood.

The

present bridge that spans

the Ouse with three arches

and a causeway has

taken

the

place of the long bridge of

Cowper's time. This long

bridge was built in

the

days

of Queen Anne by two squires,

Sir Robert Throckmorton of

Weston

Underwood

and William Lowndes of Astwood

Manor. These two gentlemen

were

sometimes

prevented from paying visits

to one another by floods, as they

lived on

opposite

sides of the Ouse. They

accordingly built the long

bridge in continuation

of

an older one, of which only

a small portion remains at

the north end. Sir

Robert

found

the material and Mr. Lowndes

the labour. This story

reminds one of a certain

road

in Berks and Bucks, the

milestones along which

record the distance

between

Hatfield

and Bath? Why Hatfield? It is

not a place of great resort or an

important

centre

of population. But when we

gather that a certain

Marquis of Salisbury

was

troubled

with gout, and had frequently to

resort to Bath for the

"cure," and

constructed

the road for his special

convenience at his own expense, we

begin to

understand

the cause of the carving of

Hatfield on the

milestones.

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION