|

OLD CROSSES |

| << OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS |

| STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS >> |

by

Sir Thomas Tresham in 1577.

Being a Recusant, he was

much persecuted for

his

religion,

and never succeeded in finishing

the work. We give an

illustration of the

quaint

little market-house at Wymondham,

with its open space beneath, and

the

upper

storey supported by stout

posts and brackets. It is entirely built

of timber and

plaster.

Stout posts support the

upper floor, beneath which is a

covered market. The

upper

chamber is reached by a quaint

rude wooden staircase.

Chipping Campden

can

boast of a handsome oblong market-house,

built of stone, having five

arches

with

three gables on the long

sides, and two arches with

gables over each on

the

short

sides. There are mullioned

windows under each

gable.

Guild

Mark and Date on doorway,

Burford, Oxon

The

city of Salisbury could at one

time boast of several halls

of the old guilds

which

flourished there. There was a

charming island of old

houses near the

cattle-

market,

which have all disappeared.

They were most picturesque

and interesting

buildings,

and we regret to have to record

that new half-timbered

structures have

been

erected in their place with sham

beams, and boards nailed on to

the walls to

represent

beams, one of the monstrosities of

modern architectural art.

The old

Joiners'

Hall has happily been

saved by the National Trust.

It has a very

attractive

sixteenth-century

faēade, though the interior

has been much altered.

Until the early

years

of the nineteenth century it

was the hall of the

guild or company of the

joiners

of

the city of New

Sarum.

Such

are some of the old

municipal buildings of England.

There are many

others

which

might have been mentioned.

It is a sad pity that so

many have disappeared

and

been replaced by modern and uninteresting

structures. If a new town

hall be

required

in order to keep pace with

the increasing dignity of an

important borough,

the

Corporation can at least preserve their

ancient municipal hall which

has so long

watched

over the fortunes of the

town and shared in its joys

and sorrows, and seek

a

fresh site for their new

home without destroying the

old.

CHAPTER

XII

CROSSES

A

careful study of the

ordnance maps of certain

counties of England reveals

the

extraordinary

number of ancient crosses

which are scattered over

the length and

breadth

of the district. Local names

often suggest the existence

of an ancient cross,

such

as Blackrod, or Black-rood, Oakenrod,

Crosby, Cross Hall, Cross

Hillock. But

if

the student sally forth to

seek this sacred symbol of

the Christian faith, he

will

often

be disappointed. The cross

has vanished, and even the

recollection of its

existence

has completely passed away.

Happily not all have

disappeared, and in

our

travels

we shall be able to discover many of

these interesting specimens of

ancient

art,

but not a tithe of those

that once existed are now to

be discovered.

Many

causes have contributed to

their disappearance. The

Puritans waged insensate

war

against the cross. It was in their eyes

an idol which must be

destroyed. They

regarded

them as popish superstitions, and

objected greatly to the

custom of

"carrying

the corse towards the

church all garnished with

crosses, which they

set

down

by the way at every cross, and

there all of them devoutly

on their knees make

prayers

for the dead."45

Iconoclastic

mobs tore down the sacred

symbol in blind

fury.

In the summer of 1643 Parliament ordered

that all crucifixes,

crosses, images,

and

pictures should be obliterated or

otherwise destroyed, and during

the same year

the

two Houses passed a resolution

for the destruction of all

crosses throughout

the

kingdom.

They ordered Sir Robert

Harlow to superintend the

levelling to the

ground

of St. Paul's Cross, Charing Cross, and

that in Cheapside, and

a

contemporary

print shows the populace

busily engaged in tearing

down the last.

Ladders

are placed against the structure,

workmen are busy hammering

the figures,

and

a strong rope is attached to the actual

cross on the summit and

eager hands are

dragging

it down. Similar scenes were

enacted in many other towns,

villages, and

cities

of England, and the wonder is

that any crosses should

have been left. But

a

vast

number did remain in order

to provide further opportunities

for vandalism and

wanton

mischief, and probably quite as

many have disappeared during

the

eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries as those which

were destroyed by

Puritan

iconoclasts.

When trade and commerce developed, and

villages grew into

towns,

and

sleepy hollows became hives

of industry, the old

market-places became

inconveniently

small, and market crosses

with their usually

accompanying stocks

and

pillories were swept away as

useless obstructions to

traffic.46

Thus

complaints

were

made with regard to the

market-place at Colne. There was no

room for the

coaches

to turn. Idlers congregated on the

steps of the cross and

interfered with the

business

of the place. It was pronounced a

nuisance, and in 1882 was swept

away.

Manchester

market cross existed until

1816, when for the

sake of utility and

increased

space it was removed. A

stately Jacobean Proclamation

cross remained at

Salford

until 1824. The Preston

Cross, or rather obelisk,

consisting of a clustered

Gothic

column, thirty-one feet

high, standing on a lofty

pedestal which rested

on

three

steps, was taken down by an

act of vandalism in 1853. The

Covell Cross at

Lancaster

shared its fate, being

destroyed in 1826 by the justices

when they

purchased

the house now used as the

judges' lodgings. A few years

ago it was

rebuilt

as a memorial of the accession of

King Edward VII.

Individuals

too, as well as corporations,

have taken a hand in the

overthrow of

crosses.

There was a wretch named Wilkinson,

vicar of Goosnargh,

Lancashire,

who

delighted in their destruction. He

was a zealous Protestant, and on

account of

his

fame as a prophet of evil

his deeds were not

interfered with by his

neighbours.

He

used to foretell the deaths

of persons obnoxious to him, and

unfortunately

several

of his prophecies were fulfilled, and he

earned the dreaded character

of a

wizard.

No one dared to prevent him,

and with his own hands he

pulled down

several

of these venerable monuments.

Some drunken men in the

early years of the

nineteenth

century pulled down the

old market cross at

Rochdale. There was a

cross

on

the bowling-green at Whalley in

the seventeenth century, the

fall of which is

described

by a cavalier, William Blundell, in

1642. When some gentlemen

came to

use

the bowling-green they found

their game interfered with

by the fallen cross. A

strong,

powerful man was induced to

remove it. He reared it,

and tried to take it

away

by wresting it from edge to

edge, but his foot

slipped; down he fell, and

the

cross

falling upon him crushed

him to death. A neighbour immediately he

heard the

news

was filled with apprehension of a similar

fate, and confessed that he

and the

deceased

had thrown down the cross.

It was considered a dangerous act to remove a

cross,

though the hope of discovering treasure

beneath it often urged men to

essay

the

task. A farmer once removed an old

boundary stone, thinking it would make

a

good

"buttery stone." But the

results were dire. Pots and

pans, kettles and

crockery

placed

upon it danced a clattering

dance the livelong night,

and spilled their

contents,

disturbed the farmer's rest,

and worrited the family.

The stone had to be

conveyed

back to its former resting-place, and

the farm again was undisturbed

by

tumultuous

spirits. Some of these

crosses have been used

for gate-posts. Vandals

have

sometimes wanted a sun-dial in their

churchyards, and have

ruthlessly

knocked

off the head and upper

part of the shaft of a cross, as

they did at Halton,

Lancashire,

in order to provide a base

for their dial. In these and

countless other

ways

have these crosses suffered,

and certainly, from the

ęsthetic and architectural

point

of view, we have to bewail

the loss of many of the most

lovely monuments of

the

piety and taste of our

forefathers.

We

will now gather up the

fragments of the ancient

crosses of England ere

these

also

vanish from our country.

They served many purposes and

were of divers kinds.

There

were preaching-crosses, on the steps of

which the early missionary

or Saxon

priest

stood when he proclaimed the

message of the gospel, ere

churches were built

for

worship. These wandering clerics

used to set up crosses in

the villages, and

beneath

their shade preached, baptized, and

said Mass. The pagan

Saxons

worshipped

stone pillars; so in order to wean

them from their superstition

the

Christian

missionaries erected these stone

crosses and carved upon them

the figures

of

the Saviour and His

Apostles, displaying before

the eyes of their hearers

the

story

of the Cross written in stone.

The north of England has

many examples of

these

crosses, some of which were

fashioned by St. Wilfrid,

Archbishop of York, in

the

eighth century. When he

travelled about his diocese

a large number of

monks

and

workmen attended him, and amongst

these were the cutters in

stone, who made

the

crosses and erected them on

the spots which Wilfrid

consecrated to the

worship

of

God. St. Paulinus and others

did the same. Hence

arose a large number of

these

Saxon

works of art, which we

propose to examine and to try to

discover the

meaning

of some of the strange sculptures

found upon them.

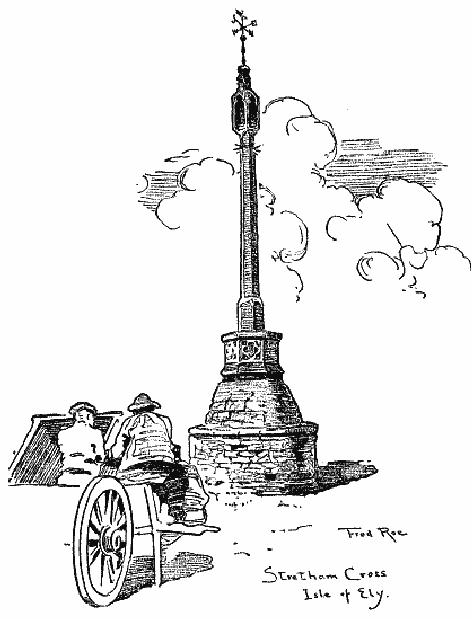

Strethem

Cross, Isle of Ely.

In

spite of iconoclasm and vandalism there

remains in England a vast

number of

pre-Norman

crosses, and it will be possible to refer

only to the most noted

and

curious

examples. These belong chiefly to

four main schools of

art--the Celtic,

Saxon,

Roman, and Scandinavian. These

various streams of northern and

classical

ideas

met and were blended

together, just as the wild

sagas of the Vikings and

the

teaching

of the gospel showed themselves

together in sculptured

representations

and

symbolized the victory of

the Crucified One over

the legends of heathendom.

The

age and period of these

crosses, the greater influence of one or

other of these

schools

have wrought differences;

the beauty and delicacy of

the carving is in

most

cases

remarkable, and we stand amazed at the

superabundance of the inventive

faculty

that could produce such

wondrous work. A great characteristic of

these

early

sculptures is the curious

interlacing scroll-work, consisting of

knotted and

interlaced

cords of divers patterns and designs.

There is an immense variety in

this

carving

of these early artists.

Examples are shown of

geometrical designs, of

floriated

ornament, of which the

conventional vine pattern is

the most frequent,

and

of

rope-work and other interlacing

ornament. We can find space

to describe only a

few

of the most

remarkable.

The

famous Bewcastle Cross

stands in the most northern

corner of the county

of

Cumberland.

Only the shaft remains. In

its complete condition it

must have been at

least

twenty-one feet high. A

runic inscription on the

west side records that it

was

erected

"in memory of Alchfrith

lately king" of Northumbria. He was

the son of

Oswy,

the friend and patron of St.

Wilfrid, who loved art so

much that he brought

workmen

from Italy to build churches

and carve stone, and he decided in favour

of

the

Roman party at the famous

Synod of Whitby. On the

south side the runes

tell

that

the cross was erected in

"the first year of Ecgfrith,

King of this realm,"

who

began

to reign 670 A.D. On the

west side are three panels

containing deeply

incised

figures,

the lowest one of which has

on his wrist a hawk, an

emblem of nobility;

the

other

three sides are filled

with interlacing, floriated, and

geometrical ornament.

Bishop

Browne believes that these

scrolls and interlacings had

their origin in

Lombardy

and not in Ireland, that

they were Italian and not

Celtic, and that the

same

sort of designs were used in

the southern land early in

the seventh century,

whence

they were brought by Wilfrid

to this country.

Another

remarkable cross is that of

Ruthwell, now sheltered from

wind and

weather

in the Durham Cathedral

Museum. It is very similar to

that at Bewcastle,

though

probably not wrought by the

same hands. In the panels

are sculptures

representing

events in the life of our

Lord. The lowest panel is

too defaced for us to

determine

the subject; on the second

we see the flight into

Egypt; on the third

figures

of Paul, the first hermit,

and Anthony, the first monk,

are carved; on the

fourth

is a representation of our Lord

treading under foot the

heads of swine; and

on

the highest there is the

figure of St. John the

Baptist with the lamb. On

the

reverse

side are the Annunciation,

the Salutation, and other

scenes of gospel

history,

and the other sides are

covered with floral and

other decoration. In

addition

to

the figures there are

five stanzas of an Anglo-Saxon poem of

singular beauty

expressed

in runes. It is the story of

the Crucifixion told in

touching words by the

cross

itself, which narrates its

own sad tale from

the time when it was a

growing

tree

by the woodside until at

length, after the body of

the Lord had been

taken

down--

The

warriors left me

there

Standing

defiled with blood.

On

the head of the cross

are inscribed the words

"Cędmon made

me"--Cędmon

the

first of English poets who

poured forth his songs in

praise of Almighty God

and

told

in Saxon poetry the story of

the Creation and of the life

of our Lord.

Another

famous cross is that at

Gosforth, which is of a much

later date and of a

totally

different character from those

which we have described. The

carvings show

that

it is not Anglian, but that

it is connected with Viking thought and

work. On it is

inscribed

the story of one of the

sagas, the wild legends of

the Norsemen, preserved

by

their scalds or bards, and

handed down from generation to

generation as the

precious

traditions of their race. On

the west side we see

Heimdal, the brave

watchman

of the gods, with his sword

withstanding the powers of

evil, and holding

in

his left hand the

Gialla horn, the terrible

blast of which shook the

world. He is

overthrowing

Hel, the grim goddess of

the shades of death, who is

riding on the

pale

horse. Below we see Loki,

the murderer of the holy

Baldur, the blasphemer

of

the

gods, bound by strong chains to

the sharp edges of a rock,

while as a

punishment

for his crimes a snake drops

poison upon his face, making

him yell

with

pain, and the earth quakes

with his convulsive

tremblings. His faithful

wife

Sigyn

catches the poison in a cup,

but when the vessel is full

she is obliged to

empty

it, and then a drop falls on

the forehead of Loki, the

destroyer, and the

earth

shakes

on account of his writhings.

The continual conflict

between good and evil

is

wonderfully

described in these old Norse

legends. On the reverse side we see

the

triumph

of Christianity, a representation of the

Crucifixion, and beneath this

the

woman

bruising the serpent's head. In

the former sculptures the

monster is shown

with

two heads; here it has only

one, and that is being

destroyed. Christ is

conquering

the powers of evil on the

cross. In another fragment at Gosforth we

see

Thor

fishing for the Midgard

worm, the offspring of Loki,

a serpent cast into

the

sea

which grows continually and threatens

the world with destruction.

A bull's head

is

the bait which Thor

uses, but fearing for

the safety of his boat, he

has cut the

fishing-line

and released the monstrous

worm; giant whales sport in

the sea which

afford

pastime to the mighty Thor.

Such are some of the strange

tales which these

crosses

tell.

There

is an old Viking legend

inscribed on the cross at Leeds.

Volund, who is the

same

mysterious person as our Wayland

Smith, is seen carrying off

a swan-maiden.

At

his feet are his

hammer, anvil, bellows, and

pincers. The cross was

broken to

pieces

in order to make way for the

building of the old Leeds

church hundreds of

years

ago, but the fragments

have been pieced together,

and we can see the

swan-

maiden

carried above the head of

Volund, her wings hanging

down and held by two

ropes

that encircle her waist.

The smith holds her by

her back hair and by the

tail of

her

dress. There were formerly

several other crosses which

have been broken up

and

used as building

material.

At

Halton, Lancashire, there is a

curious cross of inferior

workmanship, but it

records

the curious mingling of

Pagan and Christian ideas and

the triumph of the

latter

over the Viking deities. On one

side we see emblems of the

Four Evangelists

and

the figures of saints; on

the other are scenes

from the Sigurd legend.

Sigurd sits

at

the anvil with hammer and

tongs and bellows, forging a

sword. Above him is

shown

the magic blade completed,

with hammer and tongs, while

Fafni writhes in

the

knotted throes that

everywhere signify his

death. Sigurd is seen

toasting Fafni's

heart

on a spit. He has placed the

spit on a rest, and is turning it

with one hand,

while

flames ascend from the

faggots beneath. He has burnt

his finger and is

putting

it to his lips. Above are

the interlacing boughs of a

sacred tree, and sharp

eyes

may detect the talking pies

that perch thereon, to which

Sigurd is listening. On

one

side we see the noble horse

Grani coming riderless home

to tell the tale of

Sigurd's

death, and above is the pit

with its crawling snakes

that yawns for

Gunnar

and

for all the wicked

whose fate is to be turned

into hell. On the south

side are

panels

filled with a floriated design

representing the vine and

twisted knot-work

rope

ornamentation. On the west is a

tall Resurrection cross with

figures on each

side,

and above a winged and seated

figure with two others in a

kneeling posture.

Possibly

these represent the two

Marys kneeling before the

angel seated on the

stone

of the holy sepulchre on the

morning of the Resurrection of

our Lord.

A

curious cross has at last

found safety after many

vicissitudes in Hornby

Church,

Lancashire.

It is one of the most beautiful

fragments of Anglian work

that has come

down

to modern times. One panel

shows a representation of the

miracle of the

loaves

and fishes. At the foot

are shown the two

fishes and the five

loaves carved in

bold

relief. A conventional tree springs

from the central loaf, and

on each side is a

nimbed

figure. The carving is still

so sharp and crisp that it is difficult

to realize

that

more than a thousand years

have elapsed since the

sculptor finished his

task.

It

would be a pleasant task to wander

through all the English

counties and note

all

pre-Norman

crosses that remain in many

a lonely churchyard; but

such a lengthy

journey

and careful study are too

extended for our present

purpose. Some of them

were

memorials of deceased persons; others, as

we have seen, were erected

by the

early

missionaries; but preaching

crosses were erected and

used in much later

times;

and we will now examine some of

the medieval examples which

time has

spared,

and note the various uses to

which they were adapted.

The making of

graves

has often caused the

undermining and premature fall of

crosses and

monuments;

hence early examples of churchyard

crosses have often passed

away

and

medieval ones been erected

in their place. Churchyard crosses

were always

placed

at the south side of the

church, and always faced the

east. The carving and

ornamentation

naturally follow the style

of architecture prevalent at the

period of

their

erection. They had their

uses for ceremonial and

liturgical purposes,

processions

being made to them on Palm

Sunday, and it is stated in

Young's

History

of Whitby that

"devotees creeped towards them and

kissed them on Good

Fridays,

so that a cross was considered as a

necessary appendage to

every

cemetery."

Preaching crosses were also

erected in distant parts of large

parishes in

the

days when churches were few,

and sometimes market crosses were

used for this

purpose.

WAYSIDE

OR WEEPING CROSSES

Along

the roads of England stood in

ancient times many a

roadside or weeping

cross.

Their purpose is well set

forth in the work Dives et

Pauper, printed

at

Westminster

in 1496. Therein it is stated: "For

this reason ben ye crosses by

ye

way,

that when folk passynge

see the crosses, they

sholde thynke on Hym

that

deyed

on the crosse, and worshyppe Hym above

all things." Along the

pilgrim

ways

doubtless there were many,

and near villages and towns formerly

they stood,

but

unhappily they made such

convenient gate-posts when

the head was

knocked

off.

Fortunately several have

been rescued and restored. It was a

very general

custom

to erect these wayside crosses

along the roads leading to

an old parish

church

for the convenience of

funerals. There were no

hearses in those days; hence

the

coffin had to be carried a

long way, and the

roads were bad, and bodies

heavy,

and

the bearers were not

sorry to find frequent

resting-places, and the

mourners'

hearts

were comforted by constant

prayer as they passed along

the long, sad road

with

their dear ones for

the last time. These wayside

crosses, or weeping

crosses,

were

therefore of great practical utility.

Many of the old churches in

Lancashire

were

surrounded by a group of crosses,

arranged in radiating lines along

the

converging

roads, and at suitable distances

for rest. You will find such

ranges of

crosses

in the parishes of Aughton,

Ormskirk, and Burscough Priory,

and at each a

prayer

for the soul of the

departed was offered or the

De

profundis sung.

Every one

is

familiar with the famous

Eleanor crosses erected by

King Edward I to mark

the

spots

where the body of his

beloved Queen rested when it

was being borne on

its

last

sad pilgrimage to Westminster

Abbey.

MARKET

CROSSES

Market

crosses form an important

section of our subject, and

are an interesting

feature

of the old market-places

wherein they stand. Mr. Gomme

contends that they

were

the ancient meeting-places of

the local assemblies, and we

know that for

centuries

in many towns they have

been the rallying-points for

the inhabitants. Here

fairs

were proclaimed, and are

still in some old-fashioned places,

beginning with

the

quaint formula "O yes, O yes, O yes!" a

strange corruption of the old

Norman-

French

word oyez,

meaning "Hear ye." I have

printed in my book English

Villages

a

very curious proclamation of a

fair and market which

was read a few years ago

at

Broughton-in-Furness

by the steward of the lord

of the manor from the

steps of the

old

market cross. Very comely

and attractive structures

are many of these

ancient

crosses.

They vary very much in

different parts of the country

and according to the

period

in which they were erected.

The earliest are simple

crosses with steps.

Later

on

they had niches for

sculptured figures, and then in

the southern shires a kind

of

penthouse,

usually octagonal in shape, enclosed

the cross, in order to

provide

shelter

from the weather for

the market-folk. In the

north the hardy

Yorkshiremen

and

Lancastrians recked not for

rain and storms, and

few covered-in crosses can

be

found.

You will find some beautiful

specimens of these at Malmesbury,

Chichester,

Somerton,

Shepton Mallet, Cheddar,

Axbridge, Nether Stowey,

Dunster, South

Petherton,

Banwell, and other

places.

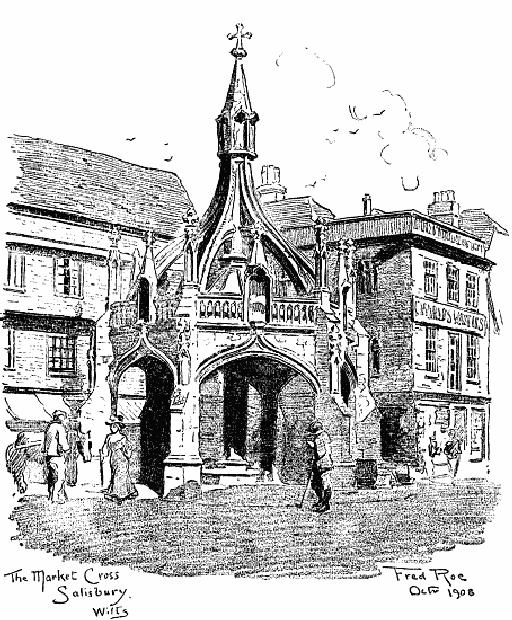

Salisbury

market cross, of which we give an

illustration, is remarkable for

its fine

and

elaborate Gothic architectural features,

its numerous niches and

foliated

pinnacles.

At one time a sun-dial and ball

crowned the structure, but

these have

been

replaced by a cross. It is usually called

the Poultry Cross. Near it and in

other

parts

of the city are quaint

overhanging houses. Though the

Guildhall has

vanished,

destroyed

in the eighteenth century,

the Joiners' Hall, the

Tailors' Hall, the

meeting-

places

of the old guilds, the

Hall of John Halle, and the

Old George are still

standing

with some of their features

modified, but not

sufficiently altered to

deprive

them

of interest.

The

Market Cross, Salisbury, Wilts.

Oct. 1908

Sometimes

you will find above a cross an

overhead chamber, which was

used for

the

storing of market appurtenances. The

reeve of the lord of the

manor, or if the

town

was owned by a monastery, or the

market and fair had been

granted to a

religious

house, the abbot's official

sat in this covered place to

receive dues from

the

merchants or stall-holders.

There

are no less than two

hundred old crosses in Somerset,

many of them

fifteenth

-century

work. Saxon crosses exist at

Rowberrow and Kelston; a

twelfth-century

cross

at Harptree; Early English

crosses at Chilton Trinity,

Dunster, and

Broomfield;

Decorated crosses at Williton,

Wiveliscombe, Bishops-Lydeard,

Chewton

Mendip, and those at Sutton

Bingham and Wraghall are

fifteenth century.

But

not all these are

market crosses. The

south-west district of England

is

particularly

rich in these relics of

ancient piety, but many

have been allowed to

disappear.

Glastonbury market cross, a

fine Perpendicular structure

with a roof, was

taken

down in 1808, and a new one

with no surrounding arcade was

erected in

1846.

The old one bore the arms of

Richard Bere, abbot of Glastonbury, who

died

in

1524. The wall of an

adjacent house has a piece of stone

carving representing a

man

and a woman clasping hands,

and tradition asserts that

this formed part of

the

original

cross. Together with the

cross was an old conduit,

which frequently

accompanied

the market cross. Cheddar Cross is

surrounded by its

battlemented

arcade

with grotesque gargoyles, a later

erection, the shaft going

through the roof.

Taunton

market cross was erected in 1867 in place

of a fifteenth-century structure

destroyed

in 1780. On its steps the

Duke of Monmouth was proclaimed

king, and

from

the window of the Old

Angel Inn Judge Jeffreys

watched with pleasure

the

hanging

of the deluded followers of

the duke from the tie-beams

of the Market

Arcade.

Dunster market cross is

known as the Yarn Market,

and was erected in

1600

by George Luttrell, sheriff of the

county of Somerset. The town was

famous

for

its kersey cloths, sometimes

called "Dunsters," which

were sold under the

shade

of

this structure.

Wymondham,

in the county of Norfolk,

standing on the high road

between

Norwich

and London, has a fine

market cross erected in

1617. A great fire

raged

here

in 1615, when three hundred

houses were destroyed, and

probably the old

cross

vanished with them, and this

one was erected to supply its

place.

The

old cross at Wells, built by

William Knight, bishop of

Bath in 1542, was

taken

down

in 1783. Leland states that

it was "a right sumptuous Peace of

worke." Over

the

vaulted roof was the

Domus

Civica or town

hall. The tolls of the

market were

devoted

to the support of the

choristers of Wells Cathedral.

Leland also records a

market

cross at Bruton which had

six arches and a pillar in

the middle "for

market

folkes

to stande yn." It was built

by the last abbot of Bruton in

1533, and was

destroyed

in 1790. Bridgwater Cross was removed in

1820, and Milverton in

1850.

Happily

the inhabitants of some

towns and villages were not

so easily deprived of

their

ancient crosses, and the people of

Croscombe, Somerset, deserve great

credit

for

the spirited manner in which

they opposed the demolition

of their cross about

thirty

years ago.

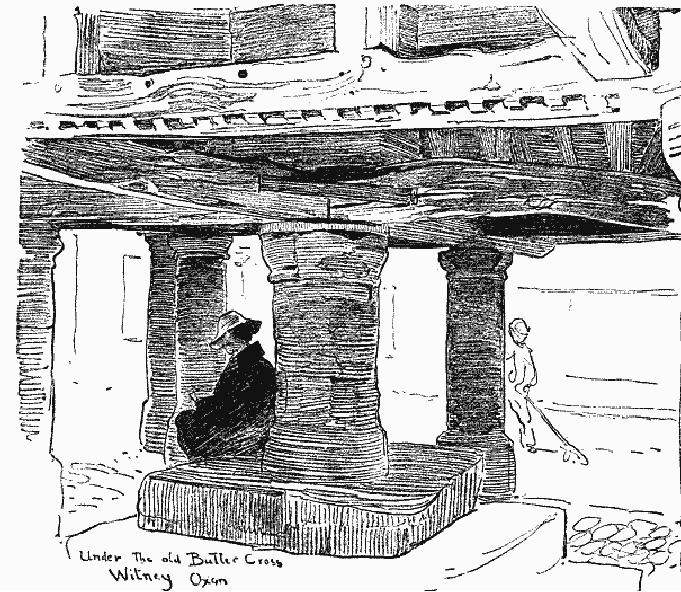

Witney

Butter Cross, Oxon, the town

whence blankets come, has a

central pillar

which

stands on three steps, the

superstructure being supported on

thirteen circular

pillars.

An inscription on the lantern above

records the following:--

GULIEIMUS

BLAKE

Armiger

de Coggs

1683

Restored

1860

1889

1894

It

has a steep roof, gabled and

stone-slated, which is not

improved by the pseudo-

Gothic

barge-boards, added during the

restorations.

Many

historical events of great importance

have taken place at these

market crosses

which

have been so hardly used.

Kings were always proclaimed

here at their

accession,

and would-be kings have also

shared that honour. Thus at

Lancaster in

1715

the Pretender was proclaimed king as

James III, and, as we have

stated, the

Duke

of Monmouth was proclaimed king at

Taunton and Bridgwater. Charles

II

received

that honour at Lancaster

market cross in 1651, nine

years before he ruled.

Banns

of marriage were published here in

Cromwell's time, and these

crosses have

witnessed

all the cruel punishments

which were inflicted on

delinquents in the

"good

old days." The last

step of the cross was

often well worn, as it was

the seat of

the

culprits who sat in the

stocks. Stocks, whipping-posts, and

pillories, of which

we

shall have much to say,

always stood nigh the cross,

and as late as 1822 a

poor

wretch

was tied to a cart-wheel at the

Colne Cross, Lancashire, and

whipped.

Sometimes

the cross is only a cross in

name, and an obelisk has supplanted

the

Christian

symbol. The change is deemed to be

attributable to the ideas of

some of

the

Reformers who desired to

assert the supremacy of the

Crown over the

Church.

Hence

they placed an orb on the

top of the obelisk

surmounted by a small,

plain

Latin

cross, and later on a large

crown took the place of the

orb and cross. At

Grantham

the Earl of Dysart erected

an obelisk which has an

inscription stating

that

it

occupies the site of the Grantham

Eleanor cross. This is a strange

error, as this

cross

stood on an entirely different site on

St. Peter's Hill and was

destroyed by

Cromwell's

troopers. The obelisk replaced

the old market cross, which

was

regarded

with much affection and

reverence by the inhabitants,

who in 1779, when

it

was taken down by the lord

of the manor, immediately

obtained a mandamus

for

its

restoration. The Mayor and

Corporation still proclaim

the Lent Fair in

quaint

and

archaic language at this

poor substitute for the

old cross.

Under

the old Butter Cross,

Whitney Oxon

One

of the uses of the market

cross was to inculcate the

sacredness of bargains.

There

is a curious stone erection in the

market-place at Middleham,

Yorkshire,

which

seems to have taken the

place of the market cross and to

have taught the

same

truth. It consists of a platform on which

are two pillars; one carries

the effigy

of

some animal in a kneeling

posture, resembling a sheep or a

cow, the other

supports

an octagonal object traditionally

supposed to represent a cheese.

The

farmers

used to walk up the opposing

flights of steps when

concluding a bargain

and

shake hands over the

sculptures.47

BOUNDARY

CROSSES

Crosses

marked in medieval times the

boundaries of ecclesiastical

properties,

which

by this sacred symbol were

thus protected from

encroachment and

spoliation.

County boundaries were also

marked by crosses and meare stones.

The

seven

crosses of Oldham marked the

estate owned by the Hospital

of St. John of

Jerusalem.

CROSSES

AT CROSS-ROADS AND HOLY WELLS

Where

roads meet and many travellers

passed a cross was often erected. It was

a

wayside

or weeping cross. There pilgrims

knelt to implore divine aid

for their

journey

and protection from outlaws

and robbers, from accidents and sudden death.

At

holy wells the cross was

set in order to remind the

frequenters of the

sacredness

of

the springs and to wean them

from all superstitious

thoughts and pagan

customs.

Sir

Walter Scott alludes to this

connexion of the cross and

well in Marmion,

when

he

tells of "a little fountain

cell" bearing the

legend:--

Drink,

weary pilgrim, drink and

pray

For

the kind soul of Sybil

Grey,

Who

built this cross and

well.

"In

the corner of a field on the

Billington Hall Farm, just

outside the

parish

of Haughton, there lies the

base, with a portion of the

shaft, of a

fourteenth-century

wayside cross. It stands within

ten feet of an old

disused

lane leading from Billington

to Bradley. Common

report

pronounced

it to be an old font. Report

states that it was said to

be a

stone

dropped out of a cart as the

stones from Billington

Chapel were

being

conveyed to Bradley to be used in

building its churchyard

wall.

A

superstitious veneration has

always attached to it. A former

owner of

the

property wrote as follows:

'The late Mr. Jackson, who was a

very

superstitious

man, once told me that a

former tenant of the farm,

whilst

ploughing

the field, pulled up the

stone, and the same day his

team of

wagon-horses

was all drowned. He then put

it into the same

place

again,

and all went on right; and

that he himself would not

have it

disturbed

upon any account.' A similar

legend is attached to another

cross.

Cross Llywydd, near Raglan,

called The White Cross,

which is

still

complete, and has evidently

been whitewashed, was moved by

a

man

from its base at some

cross-roads to his garden. From that

time he

had

no luck and all his animals

died. He attributed this to

his

sacrilegious

act and removed it to a piece of waste

ground. The next

owner

afterwards enclosed the waste with

the cross standing in

it.

"The

Haughton Cross is only a

fragment--almost precisely similar to

a

fragment

at Butleigh, in Somerset, of early

fourteenth-century date.

The

remaining part is clearly

the top stone of the base,

measuring 2 ft.

1½

in. square by 1 ft. 6 in.

high, and the lowest

portion of the shaft

sunk

into it, and measuring 1 ft.

1 in. square by 10½ in.

high. Careful

excavation

showed that the stone is

probably still standing on

its

original

site."48

"There

is in the same parish, where

there are four cross-roads, a

place

known

as 'The White Cross.' Not a

vestige of a stone remains. But on

a

slight

mound at the crossing stands

a venerable oak, now dying.

In

Monmouthshire

oaks have often been so

planted on the sites

of

crosses;

and in some cases the

bases of the crosses still

remain. There

are

in that county about thirty

sites of such crosses, and in

seventeen

some

stones still exist; and

probably there are many

more unknown to

the

antiquary, but hidden away

in corners of old paths, and in

field-

ways,

and in ditches that used to serve as

roads. A question of great

interest

arises. What were the

origin and use of these

wayside crosses?

and

why were so many of them,

especially at cross-roads, known

as

'The

White Cross'? At Abergavenny a

cross stood at cross-roads. There

is

a White Cross Street in London

and one in Monmouth, where a

cross

stood.

Were these planted by the

White Cross Knights (the

Knights of

Malta,

or of S. John of Jerusalem)? Or are they

the work of the

Carmelite,

or White, Friars? There is good authority

for the general

idea

that they were often

used as preaching stations, or as

praying

stations,

as is so frequently the case in

Brittany. But did they at

cross-

roads

in any way serve the purpose of

the modern sign-post? They

are

certainly

of very early origin. The

author of Ecclesiastical

Polity says

that

the erection of wayside

crosses was a very ancient

practice.

Chrysostom

says that they were

common in his time. Eusebius

says

that

their building was begun by

Constantine the Great to

eradicate

paganism.

Juvenal states that a

shapeless post, with a

marble head of

Mercury

on it, was erected at cross-roads to

point out the way;

and

Eusebius

says that wherever

Constantine found a statue of Bivialia

(the

Roman

goddess who delivered from

straying from the path), or

of

Mercurius

Triceps (who served the same

kind purpose for the

Greeks),

he

pulled it down and had a

cross placed upon the site.

If, then, these

cross-road

crosses of later medieval

times also had something to do

with

directions for the way,

another source of the designation

'White

Cross'

is by no means to be laughed out of

court, viz. that they

were

whitewashed,

and thus more prominent

objects by day, and

especially

by

night. It is quite certain

that many of them were

whitewashed, for

the

remains of this may still be

seen on them. And the

use of

whitewash

or plaister was far more

usual in England than is

generally

known.

There is no doubt that the

whole of the outside of the

abbey

church

of St. Albans, and of White Castle,

from top to base,

were

coated

with whitewash."49

Whether

they were whitened or not,

or whether they served as guide-posts

or

stations

for prayer, it is well that

they should be carefully preserved and

restored as

memorials

of the faith of our

forefathers, and for the

purpose of raising the heart

of

the

modern pilgrim to Christ,

the Saviour of men.

SANCTUARY

CROSSES

When

criminals sought refuge in

ancient sanctuaries, such as Durham,

Beverley,

Ripon,

Manchester, and other places

which provided the

privilege, having

claimed

sanctuary

and been provided with a

distinctive dress, they were

allowed to wander

within

certain prescribed limits. At Beverley

Minster the fugitive from

justice could

wander

with no fear of capture to a distance

extending a mile from the

church in all

directions.

Richly carved crosses marked

the limit of the sanctuary.

A peculiar

reverence

for the cross protected

the fugitives from violence

if they kept within

the

bounds.

In Cheshire, in the wild

region of Delamere Forest, there

are several

ancient

crosses erected for the

convenience of travellers; and

under their shadows

they

were safe from robbery and

violence at the hands of outlaws,

who always

respected

the reverence attached to these

symbols of Christianity.

CROSSES

AS GUIDE-POSTS

In

wild moorland and desolate

hills travellers often lost

their way. Hence

crosses

were

set up to guide them along

the trackless heaths. They

were as useful as

sign-

posts,

and conveyed an additional lesson. You will

find such crosses in the

desolate

country

on the borderland of Yorkshire and

Lancashire. They were

usually placed

on

the summit of hills. In

Buckinghamshire there are

two crosses cut in the

turf on

a

spur of the Chilterns,

Whiteleaf and Bledlow crosses,

which were probably

marks

for

the direction of travellers

through the wild and dangerous

woodlands, though

popular

tradition connects them with

the memorials of ancient

battles between the

Saxons

and Danes.

From

time out of mind crosses

have been the rallying

point for the discussion

of

urgent

public affairs. It was so in London.

Paul's Cross was the constant

meeting-

place

of the citizens of London

whenever they were excited

by oppressive laws, the

troublesome

competition of "foreigners," or any

attempt to interfere with

their

privileges

and liberties. The meetings of

the shire or hundred moots

took place

often

at crosses, or other conspicuous or

well-known objects. Hundreds

were

named

after them, such as the

hundred of Faircross in Berkshire, of Singlecross

in

Sussex,

Normancross in Huntingdonshire, and

Brothercross and Guiltcross,

or

Gyldecross,

in Norfolk.

Stories

and legends have clustered

around them. There is the

famous Stump Cross

in

Cheshire, the subject of one of

Nixon's prophecies. It is supposed to be

sinking

into

the ground. When it reaches

the level of the earth

the end of the world

will

come.

A romantic story is associated

with Mab's Cross, in Wigan,

Lancashire. Sir

William

Bradshaigh was a great warrior, and

went crusading for ten

years, leaving

his

beautiful wife, Mabel, alone

at Haigh Hall. A dastard

Welsh knight

compelled

her

to marry him, telling her

that her husband was dead,

and treated her cruelly;

but

Sir

William came back to the

hall disguised as a palmer. Mabel,

seeing in him some

resemblance

to her former husband, wept

sore, and was beaten by the

Welshman.

Sir

William made himself known

to his tenants, and raising

a troop, marched to

the

hall.

The Welsh knight fled,

but Sir William followed

him and slew him at

Newton,

for

which act he was outlawed a

year and a day. The

lady was enjoined by

her

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION