|

OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS |

| << OLD INNS |

| OLD CROSSES >> |

sojourned

at inns during their

sketching expeditions. The

"George" at Wargrave

has

a

sign painted by the

distinguished painters Mr. George Leslie,

R.A., and Mr.

Broughton,

R.A., who, when staying at

the inn, kindly painted

the sign, which is

hung

carefully within doors that it

may not be exposed to the

mists and rains of

the

Thames

valley. St. George is sallying

forth to slay the dragon on

the one side, and

on

the reverse he is refreshing himself

with a tankard of ale after

his labours. Not a

few

artists in the early stages

of their career have paid

their bills at inns by

painting

for

the landlord. Morland was

always in difficulties and adorned many a

signboard,

and

the art of David Cox,

Herring, and Sir William

Beechey has been displayed

in

this

homely fashion. David Cox's

painting of the Royal Oak at

Bettws-y-Coed was

the

subject of prolonged litigation,

the sign being valued at

�1000, the case

being

carried

to the House of Lords, and

there decided in favour of

the freeholder.

Sometimes

strange notices appear in inns.

The following rather

remarkable one was

seen

by our artist at the "County

Arms," Stone, near

Aylesbury:--

"A

man is specially engaged to do

all the cursing and swearing

that is

required

in this establishment. A dog is also kept

to do all the

barking.

Our

prize-fighter and chucker-out has

won seventy-five

prize-fights

and

has never been beaten, and is a

splendid shot with the

revolver. An

undertaker

calls here for orders every

morning."

Motor-cars

have somewhat revived the

life of the old inns on

the great coaching

roads,

but it is only the larger

and more important ones that

have been aroused

into

a

semblance of their old life.

The cars disdain the

smaller establishments, and

run

such

long distances that only a

few houses along the road

derive much benefit

from

them.

For many their days are

numbered, and it may be useful to

describe them

before,

like four-wheelers and hansom-cabs, they

have quite vanished

away.

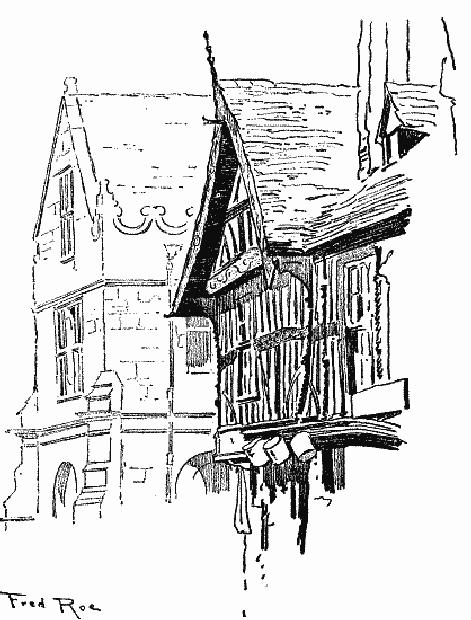

Spandril.

The Marquis of Granby Inn,

Colchester

CHAPTER

XI

OLD

MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

No

class of buildings has

suffered more than the

old town halls of our

country

boroughs.

Many of these towns have

become decayed and all their

ancient glories

have

departed. They were once flourishing

places in the palmy days of

the cloth

trade,

and could boast of fairs and

markets and a considerable number

of

inhabitants

and wealthy merchants; but

the tide of trade has flowed

elsewhere. The

invention

of steam and complex machinery

necessitating proximity to

coal-fields

has

turned its course elsewhere, to

the smoky regions of

Yorkshire and Lancashire,

and

the old town has

lost its prosperity and its

power. Its charter has

gone; it can

boast

of no municipal corporation; hence the

town hall is scarcely needed

save for

some

itinerant Thespians, an occasional

public meeting, or as a storehouse

of

rubbish.

It begins to fall into decay, and

the decayed town is not

rich enough, or

public-spirited

enough, to prop its weakened

timbers. For the sake of

the safety of

the

public it has to come

down.

On

the other hand, an influx of

prosperity often dooms the

aged town hall to

destruction.

It vanishes before a wave of

prosperity. The borough has

enlarged its

borders.

It has become quite a great

town and transacts much business. The

old

shops

have given place to grand

emporiums with large plate-glass

windows,

wherein

are exhibited the most

recent fashions of London and Paris,

and motor-cars

can

be bought, and all is very

brisk and up-to-date. The

old town hall is

now

deemed

a very poor and inadequate building. It

is small, inconvenient, and

unsuited

to

the taste of the municipal

councillors, whose ideas

have expanded with

their

trade.

The Mayor and Corporation

meet, and decide to build a

brand-new town hall

replete

with every luxury and

convenience. The old must

vanish.

And

yet, how picturesque these

ancient council chambers are.

They usually stand in

the

centre of the market-place,

and have an undercroft, the

upper storey resting

on

pillars.

Beneath this shelter the

market women display their

wares and fix their

stalls

on market days, and there

you will perhaps see the

fire-engine, at least the

old

primitive

one which was in use before a

grand steam fire-engine had

been

purchased

and housed in a station of its own.

The building has high

pointed gables

and

mullioned windows, a tiled

roof mellowed with age, and

a finely wrought

vane,

which

is a credit to the skill of

the local blacksmith. It is a

sad pity that this

"thing

of

beauty" should have to be

pulled down and be replaced by a modern

building

which

is not always creditable to

the architectural taste of

the age. A law should

be

passed

that no old town halls

should be pulled down, and

that all new ones

should

be

erected on a different site. No

more fitting place could be

found for the

storage

of

the antiquities of the town,

the relics of its old

municipal life, sketches of

its old

buildings

that have vanished, and

portraits of its worthies,

than the ancient

building

which

has for so long kept

watch and ward over its

destinies and been the scene

of

most

of the chief events

connected with its

history.

Happily

several have been spared,

and they speak to us of the

old methods of

municipal

government; of the merchant

guilds, composed of rich

merchants and

clothiers,

who met therein to transact

their common business. The

guild hall was

the

centre of the trade of the

town and of its social and

commercial life. An

amazing

amount of business was transacted

therein. If you study the

records of any

ancient

borough you will discover

that the pulse of life

beat fast in the old

guild

hall.

There the merchants met to

talk over their affairs

and "drink their

guild."

There

the Mayor came with

the Recorder or "Stiward" to

hold his courts and

to

issue

all "processes as attachementes, summons,

distresses, precepts, warantes,

subsideas,

recognissaunces, etc." The guild

hall was like a living

thing. It held

property,

had a treasury, received the

payments of freemen, levied

fines on

"foreigners"

who were "not of the

guild," administered justice,

settled quarrels

between

the brethren of the guild,

made loans to merchants, heard

the complaints of

the

aggrieved, held feasts, promoted

loyalty to the sovereign, and

insisted strongly

on

every burgess that he should

do his best to promote the

"comyn weele and

prophite

of ye saide gylde." It required

loyalty and secrecy from the

members of the

common

council assembled within its

walls, and no one was allowed to disclose

to

the

public its decisions and decrees.

This guild hall was a

living thing. Like

the

Brook

it sang:--

Men

may come and men may

go,

But

I flow on for ever."

Mayor

succeeded mayor, and burgess

followed burgess, but the

old guild hall

lived

on,

the central mainspring of

the borough's life. Therein

were stored the archives

of

the

town, the charters won, bargained

for, and granted by kings

and queens, which

gave

them privileges of trade,

authority to hold fairs and

markets, liberty to

convey

and

sell their goods in other

towns. Therein were preserved

the civic plate,

the

maces

that gave dignity to their proceedings,

the cups bestowed by royal or

noble

personages

or by the affluent members of the

guild in token of their

affection for

their

town and fellowship. Therein

they assembled to don their

robes to march in

procession

to the town church to hear Mass, or in

later times a sermon, and

then

refreshed

themselves with a feast at the charge of

the hall. The portraits of

the

worthies

of the town, of royal and

distinguished patrons, adorned the

walls, and the

old

guild hall preached daily

lessons to the townsfolk to

uphold the dignity

and

promote

the welfare of the borough,

and good feeling and the

sense of brotherhood

among

themselves.

The

Town Hall, Shrewsbury

We

give an illustration of the

town hall of Shrewsbury, a

notable building and

well

worthy

of study as a specimen of a municipal

building erected at the close of

the

sixteenth

century. The style is that

of the Renaissance with the

usual mixture of

debased

Gothic and classic details, but

the general effect is

imposing; the arches

and

parapet are especially

characteristic. An inscription over

the arch at the

north

end

records:--

"The

xvth day of June was this

building begonne, William Jones

and

Thomas

Charlton, Gent, then

Bailiffes, and was erected and covered

in

their

time, 1595."

A

full description of this building is

given in Canon Auden's

history of the town.

He

states that "under the

clock is the statue of Richard

Duke of York, father

of

Edward

IV, which was removed from

the old Welsh Bridge at

its demolition in

1791.

This is flanked by an inscription

recording this fact on the

one side, and on

the

other by the three leopards'

heads which are the arms of

the town. On the

other

end

of the building is a sun-dial,

and also a sculptured angel

holding a shield on

which

are the arms of England and France.

This was removed from the

gate of the

town,

which stood at the foot of

the castle, on its demolition in

1825. The principal

entrance

is on the west, and over

this are the arms of Queen

Elizabeth and the

date

1596.

It will be noticed that one of the

supporters is not the unicorn,

but the red

dragon

of Wales. The interior is

now partly devoted to

various municipal

offices,

and

partly used as the Mayor's

Court, the roof of which

still retains its

old

character."

It was formerly known as the

Old Market Hall, but

the business of the

market

has been transferred to the

huge but tasteless building

of brick erected at

the

top

of Mardol in 1869, the

erection of which caused the

destruction of several

picturesque

old houses which can ill be

spared.

Cirencester

possesses a magnificent town

hall, a stately Perpendicular

building,

which

stands out well against the

noble church tower of the

same period. It has a

gateway

flanked by buttresses and arcades on

each side and two upper

storeys with

pierced

battlements at the top which

are adorned with richly

floriated pinnacles. A

great

charm of the building are

the three oriel windows

extending from the top

of

the

ground-floor division to the

foot of the battlements. The

surface of the wall

of

the

fa�ade is cut into panels, and

niches for statues adorn

the faces of the

four

buttresses.

The whole forms a most

elaborate piece of Perpendicular work

of

unusual

character. We understand that it

needs repair and is in some

danger. The

aid

of the Society for the

Protection of Ancient Buildings

has been called in,

and

their

report has been sent to the

civic authorities, who will,

we hope, adopt their

recommendations

and deal kindly and tenderly with

this most interesting

structure.

Another

famous guild hall is in

danger, that at Norwich. It

has even been

suggested

that

it should be pulled down and a

new one erected, but happily

this wild scheme

has

been abandoned. Old buildings

like not new inventions,

just as old people

fear

to

cross the road lest

they should be run over by a

motor-car. Norwich

Guildhall

does

not approve of electric

tram-cars, which run close to

its north side and

cause

its

old bones to vibrate in a

most uncomfortable fashion. You

can perceive how

much

it objects to these horrid

cars by feeling the

vibration of the walls when

you

are

standing on the level of the

street or on the parapet. You will not

therefore be

surprised

to find ominous cracks in the

old walls, and the roof is

none too safe,

the

large

span having tried severely

the strength of the old oak

beams. It is a very

ancient

building, the crypt under

the east end, vaulted in

brickwork, probably

dating

from the thirteenth century,

while the main building was

erected in the

fifteenth

century. The walls are

well built, three feet in

thickness, and constructed

of

uncut flints; the east end

is enriched with diaper-work in chequers

of stone and

knapped

flint. Some new buildings

have been added on the

south side within

the

last

century. There is a clock

turret at the east end,

erected in 1850 at the cost of

the

then

Mayor. Evidently the roof

was giving the citizens

anxiety at that time, as

the

good

donor presented the clock

tower on condition that the

roof of the council

chamber

should be repaired. This famous

old building has witnessed

many strange

scenes,

such as the burning of old

dames who were supposed to

be witches, the

execution

of criminals and conspirators, the

savage conflicts of citizens and

soldiers

in

days of rioting and unrest. These good

citizens of Norwich used to

add

considerably

to the excitement of the place by

their turbulence and eagerness

for

fighting.

The crypt of the Town Hall

is just old enough to have

heard of the burning

of

the cathedral and monastery

by the citizens in 1272, and to

have seen the

ringleaders

executed. Often was there

fighting in the city, and

this same old

building

witnessed in 1549 a great riot, chiefly

directed against the

religious

reforms

and change of worship introduced by the

first Prayer Book of Edward

VI.

It

was rather amusing to see

Parker, afterwards Archbishop of

Canterbury,

addressing

the rioters from a platform,

under which stood the

spearmen of Kett, the

leader

of the riot, who took

delight in pricking the feet

of the orator with

their

spears

as he poured forth his impassioned

eloquence. In an important city

like

Norwich

the guild hall has

played an important part in

the making of England,

and

is

worthy in its old age of

the tenderest and most

reverent treatment, and even

of

the

removal from its proximity

of the objectionable electric

tram-cars.

As

we are at Norwich it would be

well to visit another old

house, which though

not

a

municipal building, is a unique specimen

of the domestic architecture of

a

Norwich

citizen in days when, as Dr.

Jessop remarks, "there was no

coal to burn in

the

grate, no gas to enlighten

the darkness of the night,

no potatoes to eat, no tea

to

drink,

and when men believed that

the sun moved round

the earth once in 365

days,

and

would have been ready to

burn the culprit who

should dare to maintain

the

contrary."

It is called Strangers' Hall, a most

interesting medieval mansion

which

had

never ceased to be an inhabited house

for at least 500 years, till it

was

purchased

in 1899 by Mr. Leonard Bolingbroke, who

rescued it from decay,

and

permits

the public to inspect its

beauties. The crypt and

cellars, and possibly

the

kitchen

and buttery, were portions

of the original house owned in 1358 by

Robert

Herdegrey,

Burgess in Parliament and Bailiff of the

City, and the present hall,

with

its

groined porch and oriel

window, was erected later

over the original

fourteenth-

century

cellars. It was inhabited by a

succession of merchants and chief

men of

Norwich,

and at the beginning of the

sixteenth century passed

into the family of

Sotherton.

The merchant's mark of

Nicholas Sotherton is painted on

the roof of the

hall.

You can see this fine hall

with its screen and gallery

and beautifully-carved

woodwork.

The present Jacobean staircase and

gallery, big oak window,

and

doorways

leading into the garden are

later additions made by

Francis Cook, grocer

of

Norwich, who was mayor of

the city in 1627. The house

probably took its

name

from

the family of Le Strange, who

settled in Norwich in the

sixteenth century. In

1610

the Sothertons conveyed the

property to Sir le Strange Mordant,

who sold it to

the

above-mentioned Francis Cook.

Sir Joseph Paine came

into possession just

before

the Restoration, and we see

his initials, with those of

his wife Emma, and

the

date

1659, in the spandrels of the

fire-places in some of the

rooms. This beautiful

memorial

of the merchant princes of

Norwich, like many other

old houses, fell into

decay.

It is most pleasant to find that it

has now fallen into

such tender hands,

that

its

old timbers have been

saved and preserved by the generous

care of its present

owner,

who has thus earned

the gratitude of all who

love antiquity.

Sometimes

buildings erected for quite

different purposes have been

used as guild

halls.

There was one at Reading, a guild

hall near the holy brook in

which the

women

washed their clothes, and

made so much noise by "beating

their

battledores"

(the usual style of washing

in those days) that the

mayor and his

worthy

brethren were often

disturbed in their deliberations, so

they petitioned the

King

to grant them the use of

the deserted church of the

Greyfriars' Monastery

lately

dissolved in the town. This

request was granted, and in the place

where the

friars

sang their services and preached,

the mayor and burgesses

"drank their guild"

and

held their banquets. When

they got tired of that

building they filched part

of the

old

grammar school from the

boys, making an upper

storey, wherein they held

their

council

meetings. The old church

then was turned into a

prison, but now happily

it

is

a church again. At last the

corporation had a town hall of

their own, which

they

decorated

with the initials S.P.Q.R.,

Romanus and Readingensis

conveniently

beginning

with the same letter.

Now they have a grand

new town hall,

which

provides

every accommodation for this

growing town.

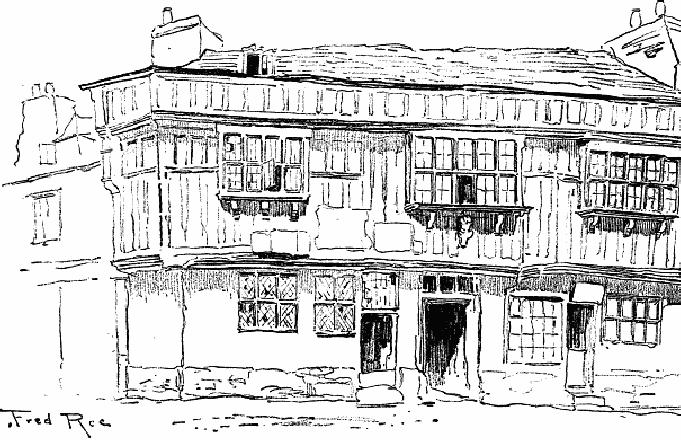

The

Greenland Fishery House,

King's Lynn. An old Guild

House of the time of

James

I

The

Newbury town hall, a

Georgian structure, has just

been demolished. It was

erected

in 1740-1742, taking the place of an

ancient and interesting guild

hall built

in

1611 in the centre of the

market-place. The councillors

were startled one day

by

the

collapse of the ceiling of

the hall, and when we last

saw the chamber tons

of

heavy

plaster were lying on the

floor. The roof was

unsound; the adjoining

street

too

narrow for the hundred

motors that raced past

the dangerous corners in

twenty

minutes

on the day of the Newbury

races; so there was no help

for the old

building;

its

fate was sealed, and it was bound to come

down. But the town

possesses a very

charming

Cloth Hall, which tells of

the palmy days of the

Newbury cloth-makers,

or

clothiers, as they were

called; of Jack of Newbury,

the famous John

Winchcombe,

or Smallwoode, whose story is

told in Deloney's humorous

old black

-letter

pamphlet, entitled The

Most Pleasant and Delectable Historie of

John

Winchcombe,

otherwise called Jacke of

Newberie, published

in 1596. He is said to

have

furnished one hundred men fully equipped

for the King's service at

Flodden

Field,

and mightily pleased Queen

Catherine, who gave him a

"riche chain of

gold,"

and

wished that God would

give the King many

such clothiers. You can see

part of

the

house of this worthy, who died in

1519. Fuller stated in the

seventeenth century

that

this brick and timber

residence had been converted

into sixteen

clothiers'

houses.

It is now partly occupied by

the Jack of Newbury Inn. A

fifteenth-century

gable

with an oriel window and

carved barge-board still remains, and

you can see a

massive

stone chimney-piece in one of the

original chambers where Jack

used to sit

and

receive his friends. Some

carvings also have been

discovered in an old house

showing

what is thought to be a carved

portrait of the clothier. It

bears the initials

J.W.,

and another panel has a

raised shield suspended by strap and

buckle with a

monogram

I.S., presumably John

Smallwoode. He was married twice,

and the

portrait

busts on each side are

supposed to represent his two

wives. Another

carving

represents

the Blessed Trinity under

the figure of a single head

with three faces

within

a wreath of oak-leaves with floriated

spandrels.44

We should

like to pursue

the

subject of these Newbury

clothiers and see Thomas

Dolman's house, which

is

so

fine and large and cost so much

money that his workpeople

used to sing a

doggerel

ditty:--

Lord

have mercy upon us miserable

sinners,

Thomas

Dolman has built a new house

and turned away all

his

spinners.

The

old Cloth Hall which

has led to this digression

has been recently restored,

and

is

now a museum.

The

ancient town of Wallingford,

famous for its castle, had a

guild hall with

selds

under

it, the earliest mention of

which dates back to the

reign of Edward II, and

occurs

constantly as the place wherein

the burghmotes were held.

The present town

hall

was erected in 1670--a

picturesque building on stone pillars.

This open space

beneath

the town hall was formerly

used as a corn-market, and so continued

until

the

present corn-exchange was erected half a

century ago. The slated roof

is

gracefully

curved, is crowned by a good vane,

and a neat dormer window

juts out

on

the side facing the

market-place. Below this is a

large Renaissance

window

opening

on to a balcony whence orators

can address the crowds

assembled in the

market-place

at election times. The walls

of the hall are hung

with portraits of the

worthies

and benefactors of the town, including

one of Archbishop Laud. A

mayor's

feast was, before the

passing of the Municipal

Corporations Act, a great

occasion

in most of our boroughs, the

expenses of which were

defrayed by the

rates.

The upper chamber in the

Wallingford town hall was

formerly a kitchen,

with

a

huge fire-place, where

mighty joints and fat capons

were roasted for the

banquet.

Outside

you can see a ring of

light-coloured stones, called the

bull-ring, where

bulls,

provided at the cost of the

Corporation, were baited. Until 1840

our Berkshire

town

of Wokingham was famous for

its annual bull-baiting on

St. Thomas's Day. A

good

man, one George Staverton, was once gored by a

bull; so he vented his

rage

upon

the whole bovine race, and

left a charity for the

providing of bulls to be baited

on

the festival of this saint,

the meat afterwards to be given to

the poor of the

town.

The

meat is still distributed, but

the bulls are no longer

baited. Here at Wokingham

there

was a picturesque old town

hall with an open undercroft,

supported on pillars;

but

the townsfolk must needs

pull it down and erect an

unsightly brick building

in

its

stead. It contains some

interesting portraits of royal and

distinguished folk

dating

from the time of Charles I,

but how the town

became possessed of

these

paintings

no man knoweth.

Another

of our Berkshire towns can

boast of a fine town hall

that has not

been

pulled

down like so many of its

fellows. It is not so old as

some, but is in itself

a

memorial

of some vandalism, as it occupies the

site of the old Market Cross,

a

thing

of rare beauty, beautifully carved and

erected in Mary's reign, but

ruthlessly

destroyed

by Waller and his troopers

during the Civil War

period. Upon the

ground

on

which it stood thirty-four years

later--in 1677--the Abingdon

folk reared their

fine

town hall; its style

resembles that of Inigo

Jones, and it has an

open

undercroft--a

kindly shelter from the

weather for market women.

Tall and graceful

it

dominates the market-place, and it is

crowned with a pretty cupola

and a fine

vane.

You can find a still more

interesting hall in the

town, part of the old

abbey,

the

gateway with its adjoining

rooms, now used as the

County Hall, and there

you

will

see as fine a collection of

plate and as choice an array

of royal portraits as

ever

fell

to the lot of a provincial

county town. One of these is

a Gainsborough. One of

the

reasons why Abingdon has

such a good store of silver plate is

that according to

their

charter the Corporation has

to pay a small sum yearly to

their High Stewards,

and

these gentlemen--the Bowyers of

Radley and the Earls of

Abingdon--have

been

accustomed to restore their fees to the

town in the shape of a gift

of plate.

We

might proceed to examine

many other of these

interesting buildings, but

a

volume

would be needed for the

purpose of recording them all.

Too many of the

ancient

ones have disappeared and

their places taken by

modern, unsightly,

though

more

convenient buildings. We may

mention the salvage of the

old market-house at

Winster,

in Derbyshire, which has

been rescued by that

admirable National

Trust

for

Places of Historic Interest or

Natural Beauty, which

descends like an angel

of

mercy

on many a threatened and abandoned

building and preserves it for

future

generations.

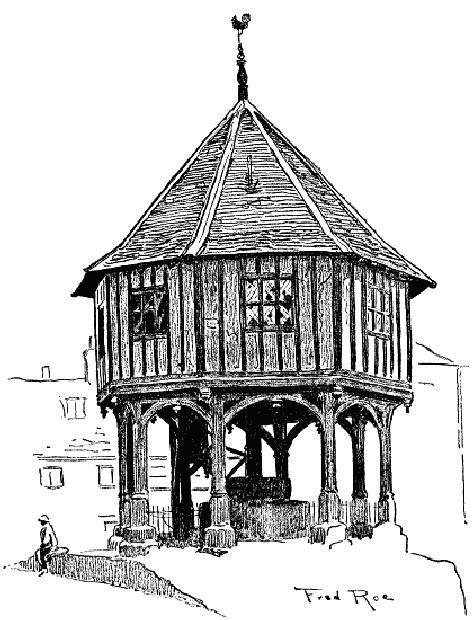

The Winster market-house is of great

age; the lower part is

doubtless

as

old as the thirteenth

century, and the upper part

was added in the

seventeenth.

Winster

was at one time an important place;

its markets were famous, and

this

building

must for very many years

have been the centre of

the commercial life of

a

large

district. But as the market

has diminished in importance,

the old market-house

has

fallen out of repair, and

its condition has caused

anxiety to antiquaries for

some

time

past. Local help has been

forthcoming under the

auspices of the

National

Trust,

in which it is now vested for

future preservation.

The

Market House, Wymondham,

Norfolk

Though

not a town hall, we may here

record the saving of a very

interesting old

building,

the Palace Gatehouse at Maidstone,

the entire demolition of

which was

proposed.

It is part of the old

residence of the Archbishops of

Canterbury, near the

Perpendicular

church of All Saints, on the banks of the

Medway, whose house at

Maidstone

added dignity to the town

and helped to make it the

important place it

was.

The Palace was originally

the residence of the Rector

of Maidstone, but was

given

up in the thirteenth century to

the Archbishop. The oldest

part of the existing

building

is at the north end, where

some fifteenth-century windows

remain. Some

of

the rooms have good old

panelling and open stone fire-places of

the fifteenth-

century

date. But decay has fallen

on the old building. Ivy is

allowed to grow over

it

unchecked, its main stems

clinging to the walls and

disturbing the stones.

Wet

has

begun to soak into the

walls through the decayed

stone sills. Happily

the

gatehouse

has been saved, and we doubt

not that the enlightened

Town Council will

do

its best to preserve this

interesting building from

further decay.

The

finest Early Renaissance

municipal building is the

picturesque guild hall

at

Exeter,

with its richly ornamented

front projecting over the

pavement and carried

on

arches. The market-house at

Rothwell is a beautifully designed

building erected

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION