|

INTRODUCTION |

| << CONTENTS |

| THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND >> |

Inmate

of the Trinity Bede House at

Castle Rising, Norfolk

339

The

Hospital for Ancient

Fishermen, Great

Yarmouth

341

Inscription

on the Hospital, King's

Lynn

343

Ancient

Inmates of the Fishermen's

Hospital, Great

347

Yarmouth

Cottages

at Evesham

348

Stalls

at Banbury Fair

350

An

Old English Fair

356

An

Ancient Maker of Nets in a

Kentish Fair

359

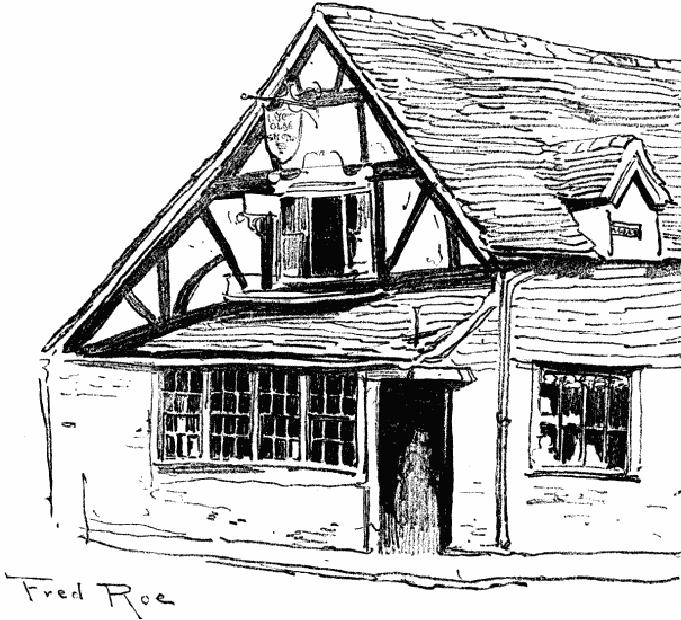

Outside

the Lamb Inn,

Burford

361

Tail

Piece

363

VANISHING

ENGLAND

CHAPTER

I

INTRODUCTION

This

book is intended not to

raise fears but to record

facts. We wish to

describe

with

pen and pencil those features of England

which are gradually

disappearing,

and

to preserve the memory of them. It

may be said that we have

begun our quest

too

late; that so much has

already vanished that it is

hardly worth while to

record

what

is left. Although much has

gone, there is still,

however, much remaining

that

is

good, that reveals the

artistic skill and taste of

our forefathers, and recalls

the

wonders

of old-time. It will be our endeavour to

tell of the old country

houses that

Time

has spared, the cottages

that grace the village

green, the stern grey walls

that

still

guard some few of our

towns, the old moot

halls and public buildings. We

shall

see

the old-time farmers and

rustics gathering together at

fair and market,

their

games

and sports and merry-makings, and

whatever relics of old

English life have

been

left for an artist and scribe of

the twentieth century to

record.

Our

age is an age of progress. Altiora

peto is

its motto. The spirit of

progress is in

the

air, and lures its votaries

on to higher flights. Sometimes they

discover that they

have

been following a mere will-o'-the-wisp,

that leads them into bog and

quagmire

whence

no escape is possible. The England of a

century, or even of half a

century

ago,

has vanished, and we find

ourselves in the midst of a

busy, bustling world

that

knows

no rest or peace. Inventions tread upon

each other's heels in one long

vast

bewildering

procession. We look back at the peaceful

reign of the pack-horse,

the

rumbling

wagon, the advent of the

merry coaching days, the

"Lightning" and the

"Quicksilver,"

the chaining of the rivers

with locks and bars, the

network of canals

that

spread over the whole

country; and then the first

shriek of the railway

engine

startled

the echoes of the

countryside, a poor powerless

thing that had to be

pulled

up

the steep gradients by a

chain attached to a big stationary

engine at the summit.

But

it was the herald of the

doom of the old-world

England. Highways and

coaching

roads, canals and rivers, were

abandoned and deserted. The

old

coachmen,

once lords of the road, ended

their days in the poorhouse,

and steam,

almighty

steam, ruled everywhere.

Now

the wayside inns wake up

again with the bellow of the

motor-car, which like

a

hideous

monster rushes through the

old-world villages, startling and

killing old

slow-footed

rustics and scampering children,

dogs and hens, and clouds of

dust

strive

in very mercy to hide the

view of the terrible rushing

demon. In a few years'

time

the air will be conquered, and

aeroplanes, balloons, flying-machines and

air-

ships,

will drop down upon us from

the skies and add a new

terror to life.

Not

in vain the distance beacons.

Forward, forward let us

range,

Let

the great world spin for

ever down the ringing

grooves of

change.

Life

is for ever changing, and

doubtless everything is for

the best in this best

of

possible

worlds; but the antiquary

may be forgiven for mourning

over the

destruction

of many of the picturesque

features of bygone times and

revelling in the

recollections

of the past. The

half-educated and the progressive--I

attach no

political

meaning to the term--delight in

their present environment, and

care not to

inquire

too deeply into the

origin of things; the study

of evolution and development

is

outside their sphere; but

yet, as Dean Church once wisely

said, "In our

eagerness

for

improvement it concerns us to be on our

guard against the temptation

of

thinking

that we can have the

fruit or the flower, and

yet destroy the root....

It

concerns

us that we do not despise

our birthright and cast away

our heritage of gifts

and

of powers, which we may

lose, but not

recover."

Every

day witnesses the destruction of

some old link with

the past life of the

people

of

England. A stone here, a buttress

there--it matters not; these

are of no

consequence

to the innovator or the

iconoclast. If it may be our

privilege to prevent

any

further spoliation of the

heritage of Englishmen, if we can awaken

any respect

or

reverence for the work of

our forefathers, the labours

of both artist and

author

will

not have been in vain.

Our heritage has been

sadly diminished, but it has

not

yet

altogether disappeared, and it is our

object to try to record some

of those objects

of

interest which are so fast

perishing and vanishing from

our view, in order

that

the

remembrance of all the treasures

that our country possesses

may not disappear

with

them.

The

beauty of our English

scenery has in many parts of

the country entirely

vanished,

never to return. Coal-pits,

blasting furnaces, factories, and

railways have

converted

once smiling landscapes and pretty

villages into an inferno of

black

smoke,

hideous mounds of ashes,

huge mills with lofty

chimneys belching

forth

clouds

of smoke that kills vegetation and

covers the leaves of trees and

plants with

exhalations.

I remember attending at Oxford a

lecture delivered by the

late Mr.

Ruskin.

He produced a charming drawing by

Turner of a beautiful old

bridge

spanning

a clear stream, the banks of which

were clad with trees and

foliage. The

sun

shone brightly, and the sky

was blue, with fleeting

clouds. "This is what

you

are

doing with your scenery,"

said the lecturer, as he

took his palette and

brushes;

he

began to paint on the glass

that covered the picture,

and in a few minutes

the

scene

was transformed. Instead of the

beautiful bridge a hideous

iron girder

structure

spanned the stream, which was no

longer pellucid and clear,

but black as

the

Styx; instead of the trees

arose a monstrous mill with

a tall chimney

vomiting

black

smoke that spread in heavy

clouds, hiding the sun and

the blue sky. "That

is

what

you are doing with

your scenery," concluded Mr.

Ruskin--a true picture

of

the

penalty we pay for trade,

progress, and the pursuit of wealth. We

are losing

faith

in the testimony of our

poets and painters to the beauty of

the English

landscape

which has inspired their

art, and much of the charm

of our scenery in

many

parts has vanished. We happily

have some of it left still

where factories are

not,

some interesting objects

that artists love to paint.

It is well that they should

be

recorded

before they too pass

away.

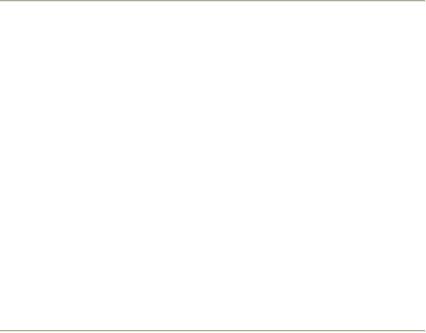

Rural

Tenements, Capel, Surrey

Old

houses of both peer and

peasant and their contents

are sooner or later doomed

to

destruction. Historic mansions full of

priceless treasures amassed by succeeding

generations

of old families fall a prey

to relentless fire. Old

panelled rooms and

the

ancient

floor-timbers understand not

the latest experiments in

electric lighting, and

yield

themselves to the flames

with scarce a struggle. Our

forefathers were

content

with

hangings to keep out the

draughts and open fireplaces to keep

them warm.

They

were a hardy race, and feared not a

touch or breath of cold.

Their degenerate

sons

must have an elaborate heating apparatus,

which again distresses the

old

timbers

of the house and fires their hearts of

oak. Our forefathers, indeed,

left

behind

them a terrible legacy of

danger--that beam in the

chimney, which has

caused

the destruction of many

country houses. Perhaps it was

not so great a source

of

danger in the days of the old

wood fires. It is deadly

enough when huge

coal

fires

burn in the grates. It is a dangerous,

subtle thing. For days, or

even for a week

or

two, it will smoulder and smoulder; and

then at last it will blaze

up, and the old

house

with all its precious

contents is wrecked.

The

power of the purse of American

millionaires also tends greatly to the

vanishing

of

much that is English--the

treasures of English art, rare

pictures and books, and

even

of houses. Some nobleman or gentleman,

through the extravagance of

himself

or

his ancestors, or on account of the

pressure of death duties, finds

himself

impoverished.

Some of our great art

dealers hear of his unhappy

state, and knowing

that

he has some fine

paintings--a Vandyke or a Romney--offer

him twenty-five

or

thirty thousand pounds for a

work of art. The temptation

proves irresistible.

The

picture

is sold, and soon finds its

way into the gallery of a

rich American, no one in

England

having the power or the good

taste to purchase it. We spend

our money in

other

ways. The following

conversation was overheard at Christie's:

"Here is a

beautiful

thing; you should buy

it," said the speaker to a

newly fledged

baronet.

"I'm

afraid I can't afford it,"

replied the baronet. "Not

afford it?" replied

his

companion.

"It will cost you infinitely less

than a baronetcy and do you

infinitely

more

credit." The new baronet

seemed rather offended. At

the great art sales

rare

folios

of Shakespeare, pictures, Sevres,

miniatures from English

houses are put up

for

auction, and of course find their

way to America. Sometimes our

cousins from

across

the Atlantic fail to secure

their treasures. They have

striven very eagerly

to

buy

Milton's cottage at Chalfont St.

Giles, for transportation to

America; but this

effort

has happily been

successfully resisted. The carved

table in the cottage

was

much

sought after, and was with

difficulty retained against an offer of

�150. An old

window

of fifteenth-century workmanship in an

old house at Shrewsbury

was

nearly

exploited by an enterprising American

for the sum of �250; and

some years

ago

an application was received by

the Home Secretary for

permission to unearth

the

body of William Penn, the

founder of Pennsylvania, from

its grave in the

burial-

ground

of Jordans, near Chalfont St.

Giles, and transport it to Philadelphia.

This

action

was successfully opposed by the trustees

of the burial-ground, but it

was

considered

expedient to watch the

ground for some time to

guard against the

possibility

of any illicit attempts at

removal.

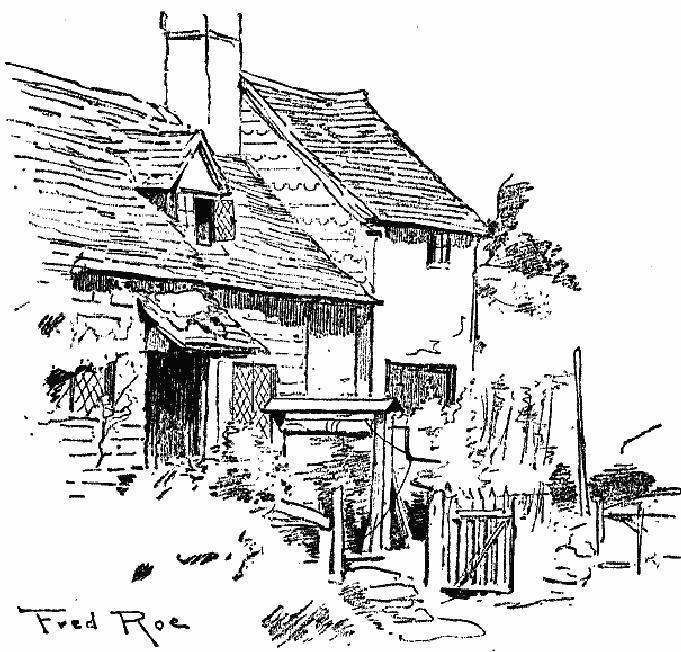

Detail

of Seventeenth-century Table in Milton's

Cottage, Chalfont St.

Giles

It

was reported that an American

purchaser had been more

successful at Ipswich,

where

in 1907 a Tudor house and corner-post, it

was said, had been secured by

a

London

firm for shipment to

America. We are glad to hear

that this report

was

incorrect,

that the purchaser was an English

lord, who re-erected the house in

his

park.

Wanton

destruction is another cause of

the disappearance of old

mansions.

Fashions

change even in house-building. Many

people prefer new lamps to

old

ones,

though the old ones

alone can summon genii and

recall the glories of the

past,

the

associations of centuries of family life,

and the stories of ancestral prowess.

Sometimes

fashion decrees the downfall

of old houses. Such a fashion

raged at the

beginning

of the last century, when

every one wanted a brand-new house

built after

the

Palladian style; and the old

weather-beaten pile that had

sheltered the family

for

generations,

and was of good old English design with

nothing foreign or strange

about

it, was compelled to give

place to a new-fangled dwelling-place

which was

neither

beautiful nor comfortable.

Indeed, a great wit once advised the

builder of

one

of these mansions to hire a

room on the other side of

the road and spend

his

days

looking at his Palladian

house, but to be sure not to

live there.

Many

old houses have disappeared

on account of the loyalty of

their owners, who

were

unfortunate enough to reside

within the regions harassed

by the Civil War.

This

was especially the case in

the county of Oxford. Still

you may see avenues

of

venerable

trees that lead to no house. The

old mansion or manor-house

has

vanished.

Many of them were put in a

posture of defence. Earthworks and moats,

if

they

did not exist before,

were hastily constructed, and

some of these houses

were

bravely

defended by a competent and brave

garrison, and were thorns in

the sides

of

the Parliamentary army. Upon

the triumph of the latter,

revenge suffered not

these

nests of Malignants to live.

Others were so battered and ruinous

that they

were

only fit residences for

owls and bats. Some loyal

owners destroyed the

remains

of their homes lest they

should afford shelter to the

Parliamentary forces.

David

Walter set fire to his house

at Godstow lest it should

afford accommodation

to

the "Rebels." For the

same reason Governor Legge

burnt the new

episcopal

palace,

which Bancroft had only

finished ten years before at Cuddesdon.

At the

same

time Thomas Gardiner burnt

his manor-house in Cuddesdon village,

and

many

other houses were so battered

that they were left

untenanted, and so fell to

ruin.1

Sir

Bulstrode Whitelock describes

how he slighted the works at

Phillis Court,

"causing

the bulwarks and lines to be digged

down, the grafts [i.e.

moats] filled, the

drawbridge

to be pulled up, and all

levelled. I sent away the great

guns, the

granadoes,

fireworks, and ammunition, whereof

there was good store in the fort.

I

procured

pay for my soldiers, and

many of them undertook the

service in Ireland."

This

is doubtless typical of what

went on in many other houses.

The famous royal

manor-house

of Woodstock was left battered and

deserted, and "haunted," as

the

readers

of Woodstock

will

remember, by an "adroit and humorous

royalist named

Joe

Collins," who frightened the

commissioners away by his

ghostly pranks. In

1651

the old house was gutted and

almost destroyed. The war

wrought havoc with

the

old houses, as it did with

the lives and other

possessions of the

conquered.

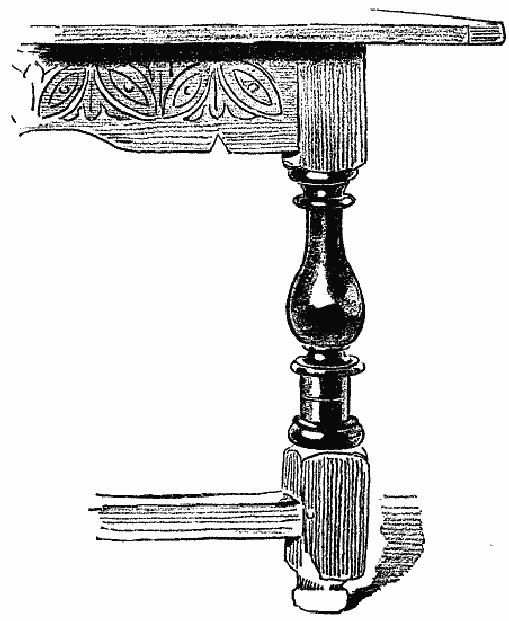

Seventeenth-century

Trophy

But

we are concerned with times

less remote, with the

vanishing of historic

monuments,

of noble specimens of architecture,

and of the humble dwellings

of the

poor,

the picturesque cottages by

the wayside, which form

such attractive

features

of

the English landscape. We have

only to look at the west

end of St. Albans

Abbey

Church,

which has been "Grimthorped"

out of all recognition, or at

the over-

restored

Lincoln's Inn Chapel, to see

what evil can be done in the

name of

"Restoration,"

how money can be lavishly

spent to a thoroughly bad

purpose.

Property

in private hands has suffered no

less than many of our

public buildings,

even

when the owner is a lover of

antiquity and does not

wish to remove and to

destroy

the objects of interest on

his estate. Estate agents

are responsible for

much

destruction.

Sir John Stirling Maxwell,

Bart., F.S.A., a keen arch�ologist,

tells how

an

agent on his estate transformed a

fine old grim

sixteenth-century fortified

dwelling,

a very perfect specimen of its

class, into a house for

himself, entirely

altering

the character of its

appearance, adding a lofty

oriel and spacious

windows

with

a new door and staircase,

while some of the old

stones were made to adorn

a

rockery

in the garden. When he was

abroad the elaborately

contrived entrance

for

the

defence of a square fifteenth-century

keep with four square

towers at the

corners,

very curious and complete,

were entirely obliterated by a

zealous mason.

In

my own parish I awoke one

day to find the old

village pound entirely

removed

by

order of an estate agent, and a

very interesting stand near the

village smithy for

fastening

oxen when they were shod

disappeared one day, the

village publican

wanting

the posts for his

pig-sty. County councils

sweep away old bridges

because

they

are inconveniently narrow and

steep for the tourists'

motors, and deans and

chapters

are not always to be relied

upon in regard to their theories of

restoration,

and

squire and parson work sad

havoc on the fabrics of old

churches when they

are

doing

their best to repair them.

Too often they have

decided to entirely

demolish

the

old building, the most

characteristic feature of the

English landscape, with

its

square

grey tower or shapely spire, a

tower that is, perhaps,

loopholed and

battlemented,

and tells of turbulent times

when it afforded a secure

asylum and

stronghold

when hostile bands were

roving the countryside.

Within, piscina,

ambrey,

and rood-loft tell of the

ritual of former days. Some

monuments of knights

and

dames proclaim the

achievements of some great local

family. But all

this

weighs

for nothing in the eyes of

the renovating squire and parson.

They must have

a

grand, new, modern church

with much architectural

pretension and fine

decorations

which can never have the

charm which attaches to the

old building. It

has

no memories, this new

structure. It has nothing to

connect it with the

historic

past.

Besides, they decree that it

must not cost too much.

The scheme of

decoration

is

stereotyped, the construction

mechanical. There is an entire

absence of true

feeling

and of any real inspiration of

devotional art. The design is

conventional, the

pattern

uniform. The work is often

scamped and hurried, very

different from the

old

method

of building. We note the

contrast. The medieval

builders were never in

a

hurry

to finish their work. The

old fanes took centuries to

build; each

generation

doing

its share, chancel or nave, aisle or

window, each trying to make

the church as

perfect

as the art of man could

achieve. We shall see how

much of this sound

and

laborious

work has vanished, a prey to

restoration and ignorant renovation.

We

shall

see the house-breaker at work in

rural hamlet and in country

town. Vanishing

London

we shall leave severely

alone. Its story has

been already told in a large

and

comely

volume by my friend Mr. Philip

Norman. Besides, is there

anything that has

not

vanished, having been doomed to

destruction by the march of progress,

now

that

Crosby Hall has gone the

way of life in the Great

City? A few old halls of

the

City

companies remain, but most of

them have given way to

modern palaces; a few

City

churches, very few, that

escaped the Great Fire, and

every now and again we

hear

threatenings against the masterpieces of

Wren, and another City

church has

followed

in the wake of all the

other London buildings on

which the destroyer

has

laid

his hand. The site is so

valuable; the modern world

of business presses out

the

life

of these fine old edifices.

They have to make way for

new-fangled erections

built

in the modern French style

with sprawling gigantic

figures with bare

limbs

hanging

on the porticoes which seem

to wonder how they ever

got there, and

however

they were to keep themselves

from falling. London is hopeless! We

can

but

delve its soil when

opportunities occur in order to

find traces of Roman

or

medieval

life. Churches, inns, halls,

mansions, palaces, exchanges have

vanished,

or

are quickly vanishing, and we

cast off the dust of

London streets from our

feet

and

seek more hopeful

places.

Old

Shop, formerly standing in Cliffe

High Street, Lewes

But

even in the sleepy hollows

of old England the pulse

beats faster than of

yore,

and

we shall only just be in

time to rescue from oblivion

and the house-breaker

some

of our heritage. Old city

walls that have defied

the attacks of time and of

Cromwell's

Ironsides are often in danger

from the wiseacres who

preside on

borough

corporations. Town halls picturesque and

beautiful in their old age

have to

make

way for the creations of

the local architect. Old

shops have to be pulled

down

in

order to provide a site for a

universal emporium or a motor

garage. Nor are

buildings

the only things that

are passing away. The

extensive use of

motor-cars

and

highway vandalism are

destroying the peculiar

beauty of the English

roadside.

The

swift-speeding cars create

clouds of white dust which

settles upon the

hedges

and

trees, covering them with it

and obscuring the wayside

flowers and hiding

all

their

attractiveness. Corn and grass

are injured and destroyed by

the dust clouds.

The

charm and poetry of the

country walk are destroyed

by motoring demons, and

the

wayside cottage-gardens, once the most

attractive feature of the

English

landscape,

are ruined. The elder

England, too, is vanishing in

the modes, habits,

and

manners of her people. Never was

the truth of the old

oft-quoted Latin

proverb--Tempora

mutantur, et nos mutamur in

illis--so

pathetically emphatic as

it

is to-day. The people are

changing in their habits and

modes of thought. They

no

longer

take pleasure in the simple

joys of their forefathers.

Hence in our

chronicle

of

Vanishing England we shall

have to refer to some of those strange

customs

which

date back to primeval ages,

but which the railways,

excursion trains, and

the

schoolmaster

in a few years will render

obsolete.

In

recording the England that

is vanishing the artist's

pencil will play a

more

prominent

part than the writer's

pen. The graphic sketches

that illustrate this

book

are

far more valuable and

helpful to the discernment of

the things that remain

than

the

most effective descriptions. We

have tried together to

gather up the

fragments

that

remain that nothing be lost;

and though there may be much

that we have not

gathered,

the examples herein given of

some of the treasures that

are left may be

useful

in creating a greater reverence for

the work bequeathed to us by

our

forefathers,

and in strengthening the hands of those

who would preserve

them.

Happily

we are still able to use the

present participle, not the past. It is

vanishing

England,

not vanished, of which we

treat; and if we can succeed in promoting

an

affection

for the relics of antiquity

that time has spared,

our labours will not

have

been

in vain or the object of

this book unattained.

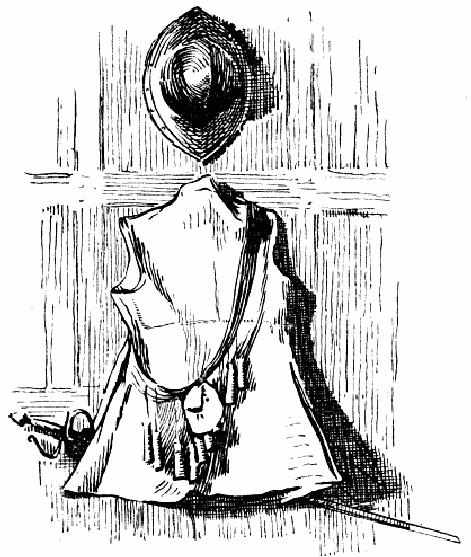

Paradise

Square, Banbury

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION