|

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Lecture

41

Lecture

41. Asking

Users

Learning

Goals

As the

aim of this lecture is to

introduce you the study of

Human Computer

Interaction,

so that after studying this

you will be able to:

� Discuss

when it is appropriate to use

different types of interviews

and

questionnaires.

� Teach

you the basics of questionnaire

design.

� Describe

how to do interviews, heuristic

evaluation, and

walkthroughs.

� Describe

how to collect, analyze, and

present data collected by

the

techniques

mentioned above.

� Enable

you to discuss the strengths

and limitations of the

techniques and

select

appropriate ones for your

own use.

Introduction

41.1

In the

last lecture we looked at

observing users. Another way

of finding out what

users

do, what they want to do

like, or don't like is to ask

them. Interviews and

questionnaires

are well-established techniques in

social science research,

market

research,

and human-computer interaction.

They are used in "quick and

dirty"

evaluation,

in usability testing, and in field

studies to ask about facts,

behavior, beliefs,

and

attitudes.

Interviews

and questionnaires can be

structured, or flexible and

more

like a

discussion, as in field studies. Often

interviews and observation go

together in

field

studies, but in this lecture we focus

specifically on interviewing

techniques.

The

first part of this lecture

discusses interviews and

questionnaires. As with

observation,

these techniques can be used in the

requirements activity, but in

this

lecture

we focus on their use in

evaluation. Another way of

finding out how well

a

system is

designed is by asking experts

for then opinions. In the

second part of the

lecture,

we look at the techniques of

heuristic evaluation and

cognitive walkthrough.

These

methods involve predicting how

usable interfaces are (or are

not).

Asking users:

interviews

41.2

Interviews

can be thought of as a "conversation

with a purpose" (Kahn and

Cannell,

1957).

How like an ordinary

conversation the interview is depends on

the '' questions

to be answered

and the type of interview

method used. There are

four main types of

interviews:

open-ended

or unstructured, structured,

semi-structured, and

group

interviews

(Fontana and Frey, 1994).

The first three types

are named according to

how

much control the interviewer

imposes on the conversation by following

a

predetermined

set of questions. The

fourth involves a small

group guided by an

interviewer

who facilitates discussion of a specified

set of topics.

The most

appropriate approach to interviewing

depends on the evaluation goals,

the

questions

to be addressed, and the

paradigm adopted. For

example, it the goal is

to

gain

first impressions about how

users react to a new design

idea, such as an

interactive

sign, then an informal,

open-ended interview is often

the best approach.

But

if the

goal is to get feedback

about a particular design

feature, such as the layout

of a

new

web browser, then a

structured interview or questionnaire is

often better. This is

because

the goals and questions

are more specific in the

latter case.

390

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Developing

questions and planning an

interview

When

developing interview questions,

plan to keep them short,

straightforward and

avoid

asking too many. Here are

some guidelines (Robson,

1993):

� Avoid

long questions because they

are difficult to remember.

� Avoid

compound sentences by splitting

them into two separate

questions. For

example,

instead of, "How do you

like this cell phone

compared with

previous

ones that you have

owned?" Say, "How do you like

this cell

phone?

Have you owned other

cell phones? If so, "How did

you like it?"

This is

easier for the interviewee

and easier for the

interviewer to record.

Avoid

using jargon and language

that the interviewee may not

understand

�

but

would be too embarrassed to

admit.

Avoid

leading questions such as,

"Why do you like this style

of

�

interaction?"

It used on its own, this

question assumes that the

person did

like

it.

Be alert

to unconscious biases. Be sensitive to

your own biases and

strive

�

for

neutrality in your

questions.

Asking

colleagues to review the

questions and running a

pilot study will help

to

identify

problems in advance and gain

practice in interviewing.

When

planning an interview, think about

interviewees who may be

reticent to

answer

questions or who are in a hurry.

They are doing you a favor, so

tr y to

make it

as pleasant for them as possible

and try to make the

interviewee feel

comfortable.

Including the following steps will

help you to achieve

this

(Robson,

1993):

1. An Introduction

in

which the interviewer

introduces himself and

explains

why he is

doing the interview,

reassures interviewees about

the ethical

issues,

and asks if they mind

being recorded, if appropriate.

This should be

exactly

the same for each

interviewee.

2. A warmup

session

where easy, non-threatening

questions come first.

These

may

include questions about

demographic information, such as "Where

do

you

live?"

3. A main

session

in which the questions are

presented in a logical sequence,

with

the more difficult ones at

the end.

4. A cool-off

period consisting

of a few easy questions (to

defuse tension if it

has

arisen).

5. A closing

session

in which the interviewer

thanks the interviewee

and

switches

off the recorder or puts

her notebook away, signaling

that the

interview

has ended.

The

golden rule is to be professional.

Here is some further advice

about conducting

interviews

(Robson. 1993):

� Dress in a

similar way to the

interviewees if possible. If in

doubt,

dress

neatly and avoid standing

out.

� Prepare

an informed consent form and

ask the interviewee to sign

it.

� If

you are recording the

interview, which is advisable,

make sure

your

equipment works in advance

and you know how to

use it.

391

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Record

answers exactly: do not make

cosmetic adjustments,

correct,

�

or change

answers in any way.

Unstructured

interviews

Open-ended

or unstructured interviews are at one

end of a spectrum of how

much

control

the interviewer has on the

process. They are more like

conversations that

focus on

a particular topic and may

often go into considerable depth.

Questions

posed by

the interviewer are open, meaning

that the format and content of

answers is

not

predetermined. The interviewee is

free to answer as fully or as briefly as

she

wishes.

Both interviewer and

interviewee can steer the

interview. Thus one of the

skills

necessary for this type of

interviewing is to make sure

that answers to

relevant

questions

are obtained. It is therefore advisable

to be organized and have a

plan of

the

main things to be covered. Going in

without an agenda to accomplish a goal is not

advisable,

and should not to be

confused with being open to

new information and

ideas.

A benefit

of unstructured interviews is that

they generate rich data.

Interviewees

often

mention things that the

interviewer may not have

considered and can be

further

explored.

But this benefit often

comes at a cost. A lot of unstructured

data is

generated,

which can be very time-consuming

and difficult to analyze. It is

also

impossible

to replicate the process, since each

interview takes on its own

format.

Typically

in evaluation, there is no attempt to

analyze these interviews in

detail.

Instead,

the evaluator makes notes or records

the session and then goes

back later to

note

the main issues of

interest.

The

main points to remember when

conducting an unstructured interview

are:

� Make

sure you have an interview

agenda that supports the

study goals and

questions

(identified through the

DECIDE framework).

� Be

prepared to follow new lines

of enquiry that contribute to

your agenda.

� Pay

attention to ethical issues,

particularly the need to get

informed consent.

� Work

on gaining acceptance and putting

the interviewees at ease.

For

example,

dress as they do and take

the time to learn about

their world.

� Respond

with sympathy if appropriate,

but be careful not to put

ideas into

the heads

of respondents.

� Always

indicate to the interviewee

the beginning and end of

the interview

session.

� Start

to order and analyze your

data as soon as possible

after the interview

Structured

interviews

Structured

interviews pose predetermined questions

similar to those in a

questionnaire.

Structured interviews are

useful when the study's

goals arc clearly

understood

and specific questions can

he identified. To work best,

the questions

need to

he short and clearly worded.

Responses may involve selecting

from a set

of

options that are read

aloud or presented on paper.

The questions should

be

refined

by asking another evaluator to

review them and by running a

small pilot

study.

Typically the questions are

closed, which means that

they require a

precise

answer.

The same questions are used

with each participant so the

study is

standardized.

392

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Semi-structured

interviews

Semi-structured

interviews combine features of

structured and unstructured

inter

views

and use both closed

and open questions. For

consistency the interviewer

has

a basic

script for guidance, so that

the same topics arc

covered with each

interviewee.

The interviewer starts with

preplanned questions and

then probes the

interviewee

to say more until no new

relevant information is forthcoming.

For

example:

Which

websites do you visit most frequently?

<Answer> Why?

<Answer

mentions

several but stresses that

prefers hottestmusic.com> And

why do

you

like it? <Answer> Tell

me more about x? <Silence,

followed by an

answer>

Anything else? <Answer>Thanks.

Are there any other

reasons

that

you haven't

mentioned?

It is

important not to preempt an

answer by phrasing a question to suggest

that a

particular

answer is expected. For

example. "You seemed to like this

use of

color..."

assumes that this is the

case and will probably

encourage the

interviewee

to answer

that this is true so as not

to offend the interviewer.

Children are

particularly

prone to behave in this way.

The body language of the

interviewer, for

example,

whether she is smiling,

scowling, looking disapproving,

etc., can have a

strong

influence.

Also

the interviewer needs to accommodate

silence and not to move on

too

quickly.

Give the person time to

speak. Probes are a device

for getting more

information,

especially neutral probes such

as, "Do you want to tell me

anything

else" You

may also prompt the

person to help her along.

For example, if the

interviews

is talking about a computer

interface hut has forgotten

the name of a

key

menu item, you might

want to remind her so that

the interview can

proceed

productively

However, semi-structured interviews

are intended to be

broadly

replicable.

So probing and prompting

should aim to help the

interview along

without

introducing bias

Group

interviews

One

form of group interview is

the focus group that is

frequently used in

marketing,

political

campaigning, and social

sciences research. Normally

three to 10 people

are

involved.

Participants are selected to provide a

representative sample of typical

users;

they

normally share certain characteristics.

For example, in an evaluation of a

university

website,

a group of administrators, faculty,

and students may be called

to form three

separate

focus groups because they use

the web for different

purposes.

The

benefit of a focus group is

that it allows diverse or

sensitive issues to be raised

that

would otherwise be missed.

The method assumes that

individuals develop

opinions

within a

social context by talking with others.

Often questions posed to focus

groups

seem

deceptively simple but the

idea is to enable people to put

forward their own

opinions

in a supportive environment. A preset agenda is

developed to guide

the

discussion

but there is sufficient

flexibility for a facilitator to

follow unanticipated

issues as

they are raised. The

facilitator guides and

prompts discussion and skillfully

encourages

quiet people to participate and

stops verbose ones from

dominating the

discussion.

The discussion is usually recorded

for later analysis in which

participants

may be

invited to explain their

comments more fully.

393

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Focus

groups appear to have high validity

because the method is

readily understood

and

findings

appear believable (Marshall and

Rossman, 1999). Focus groups

are also

attractive

because they are low-cost,

provide quick results, and

can easily be scaled

to

gather more

data. Disadvantages are that the

facilitator needs to be skillful so

that time

is not

wasted on irrelevant issues. It

can also be difficult to get

people together in a

suitable

location. Getting time with

any interviewees can be difficult,

but the problem is

compounded

with focus groups because of

the number of people

involved. For

example, in a

study to evaluate a university website

the evaluators did not expect

that

getting

participants would be a problem. However,

the study was scheduled near

the

end of a

semester when students had

to hand in their work, so strong

incentives were

needed to

entice the students to participate in

the study. It took an

increase in the

participation

fee and a good lunch to

convince students to

participate.

Other

sources of interview-like

feedback

Telephone

interviews are a good way of

interviewing people with

whom you cannot

meet. You

cannot see body language,

but apart from this

telephone interviews have

much in common

with face-to-face interviews.

Online

interviews, using either

asynchronous communication as in email

or

synchronous

communication as in chats, can also be

used. For interviews that

involve

sensitive

issues, answering questions

anonymously may be preferable to

meeting face

to face. If,

however, face-to-face meetings are

desirable but impossible

because of

geographical

distance, video-conferencing systems can

be used. Feedback about a

product

can also be obtained from customer

help lines, consumer groups,

and online

customer

communities that provide

help and support.

At

various stages of design, it is

useful to get quick feedback

from a few users.

These

short

interviews are often more

like conversations in which

users are asked their

opinions.

Retrospective interviews can be done when

doing field studies to check

with

participants

that the interviewer has

correctly understood what

was happening.

Data

analysis and

interpretation

Analysis

of unstructured interviews can be

time-consuming, though their contents

can

be rich.

Typically each interview

question is examined in depth in a

similar way to

observation

data. A coding form may he

developed, which may he

predetermined or

may he

developed during data collection as

evaluators are exposed to the range

of

issues

and learn about their

relative importance Alternatively,

comments may he

clustered

along themes and anonymous quotes

used to illustrate points of

interest.

Tools

such a NUDIST and

Ethnography can be useful

for qualitative analyses.

Which

type of

analysis is done depends on

the goals of the study, as

does whether the

whole

interview

is transcribed, only part of it, or none of it. Data

from structured interviews

is

usually analyzed quantitatively as in

questionnaires, which we discuss

next.

Asking users:

questionnaires

41.3

Questionnaires

are a well-established technique

for collecting demographic

data

and

users' opinions. They are

similar to interviews and can

have closed

or

open

questions.

Effort and skill are needed to ensure

that questions are clearly

worded

and

the data collected can be

analyzed efficiently. Questionnaires can

be used on

their

own or in conjunction with

other methods to clarify or deepen

understanding.

The

questions asked in a questionnaire,

and those used in a structured

interview

are

similar, so how do you know

when to use which technique?

One advantage of

394

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

questionnaires

is that they can be

distributed to a large number of

people. Used in

this

way, they provide evidence

of wide general opinion. On

the other hand,

structured

interviews are easy and

quick to conduct in situations in

which people

will not

stop to complete a

questionnaire.

Designing

questionnaires

Many

questionnaires start by asking

for basic demographic information

(e.g.. gender.

age)

and details of user

experience (e.g., the time or

number of years spent using

computers,

level of expertise, etc.).

This background information is

useful in finding

out

the range within the sample

group. For instance, a group

of people who are

using

the

web for the first

time are likely to express

different opinions to another

group

with five

years of web experience. From

knowing the sample range, a

designer

might

develop two different

versions or veer towards the

needs of one of the

groups

more

because it represents the target

audience.

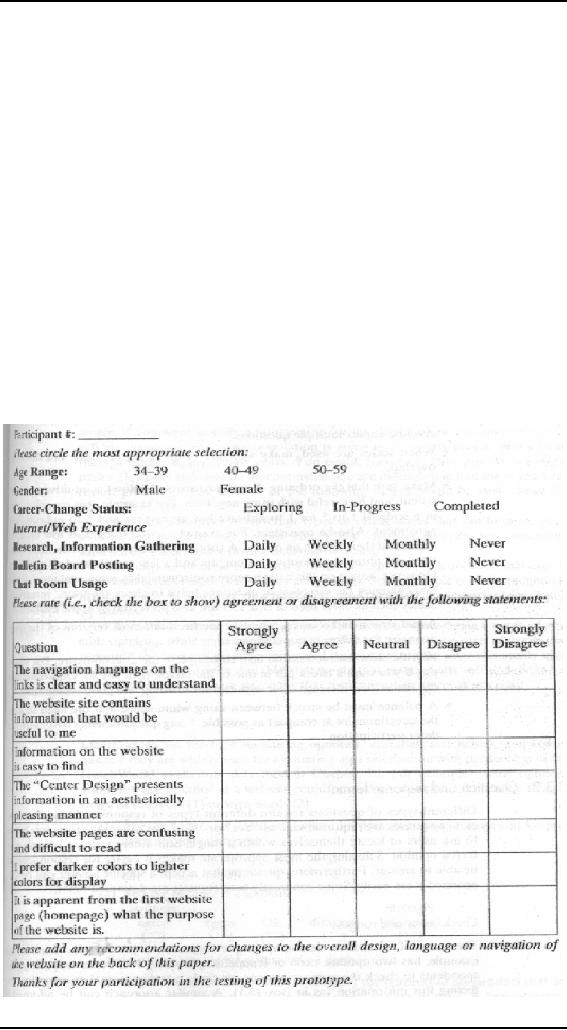

Following

the general questions, specific questions

that contribute to the

evaluation goal

are asked. If

the questionnaire is long,

the questions may be

subdivided into

related

topics to

make it easier and more

logical to complete. Figure

below contains an

excerpt

from a paper questionnaire

designed to evaluate users" satisfaction

with

some

specific features of a prototype

website for career changers aged

34-59

years.

395

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

following is a checklist of general

advice for designing a

questionnaire:

� Make

questions clear and

specific.

� When

possible, ask closed

questions and offer a range

of answers.

� Consider

including a "no-opinion" option for

questions that seek opinions.

� Think

about the ordering of questions.

The impact of a question can

he

influenced

by question order. General

questions should precede

specific

ones.

� Avoid

complex multiple questions.

� When

scales are used, make sure

the range is appropriate and does

not

overlap.

� Make

sure that the ordering of

scales (discussed below) is intuitive

and

consistent,

and be careful with using

negatives. For example, it is

more

intuitive in a scale

of 1 to 5 for 1 to indicate low agreement

and 5 to

indicate

high agreement. Also be consistent.

For example, avoid using

1

as low on

some scales and then as

high on others. A subtler problem

occurs

when

most questions are phrased

as positive statements and a

few are

phrased

as negatives. However, advice on

this issue is more

controversial as

�

some

evaluators argue that

changing the direction of

questions helps to

check

the

users' intentions.

Avoid

jargon and consider whether

you need different versions

of the

�

questionnaire

for different

populations.

Provide

clear instructions on how to

complete the questionnaire.

For

�

example,

if you want a check put in

one of the boxes, then

say so.

Questionnaires

can make their message

clear with careful wording

and good

typography.

A balance

must be struck between using

white space and the need to

keep

�

the

questionnaire as compact as possible.

Long questionnaires cost more

and

deter

participation.

Question

and response format

Different

types of questions require

different types of responses. Sometimes

discrete

responses

arc required, such as ''Yes"

or "No." For other questions

it is better to ask

users to

locate themselves within a range. Still

others require a single

preferred

opinion.

Selecting the most appropriate

makes it easier for respondents to be

able to

answer.

Furthermore, questions that

accept a specific answer can be

categorized more

easily.

Some commonly used formats

are described below.

Check

boxes and ranges

The

range of answers to demographic

questionnaires is predictable. Gender,

for

example,

has two options, male or

female, so providing two

boxes and asking

respondents to

check the appropriate one,

or circle a response, makes

sense for

collecting

this information. A similar

approach can be adopted if

details of age are

needed.

But since some people do

not like to give their

exact age many

questionnaires

ask

respondents to specify their age as a

range. A common design error

arises when

the

ranges overlap. For example,

specifying two ranges as

15-20, 20-25 will

cause

396

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

confusion:

which box do people who are

20 years old check? Making the

ranges 14-

19,

20-24 avoids this

problem.

A

frequently asked question about

ranges is whether the

interval must be equal in

all

cases.

The answer is that it depends on what

you want to know. For

example, if you

want to

collect information for the

design of an e-commerce site to sell

life insurance,

the

target population is going to be

mostly people with jobs in

the age range of,

say,

21-65

years. You could, therefore,

have just three ranges:

under 21, 21-65 and

over

65. In

contrast, if you are interested in

looking at ten-year cohort

groups for people

over 21

the following ranges would

he best: under 21, 22-31,

32-41, etc.

Administering

questionnaires

Two

important issues when using

questionnaires are reaching a

representative

sample of

participants and ensuring a

reasonable response rate.

For large surveys,

potential

respondents need to be selected using a

sampling technique.

However,

interaction

designers tend to use small

numbers of participants, often fewer

than

twenty

users. One hundred percent

completion rates often are

achieved with

these

small samples, but with

larger, more remote

populations, ensuring

that

surveys

are returned is a well-known problem.

Forty percent return is

generally

acceptable

for many surveys but

much lower rates are

common.

Some

ways of encouraging a good

response include:

� Ensuring

the questionnaire is well

designed so that participants do

not

get

annoyed and give

up.

� Providing

a short overview section and telling

respondents to complete

just

the short version if they do

not have time to complete

the whole

thing.

This ensures that you get

something useful

returned.

� Including a

stamped, self-addressed envelope for its

return.

� Explaining

why you need the

questionnaire to be completed and

assuring

anonymity.

� Contacting

respondents through a follow-up

letter, phone call or

email.

� Offering

incentives such as payments.

Online

questionnaires

Online

questionnaires are becoming

increasingly common because

they are effective

for

reaching large numbers of people

quickly and easily. There

are two types:

email

and

web-based. The main

advantage of email is that

you can target specific

users.

However,

email questionnaires are

usually limited to text, whereas

web-based

questionnaires

are more flexible and

can include check boxes,

pull-down and pop-up

menus,

help screens, and graphics,

web-based questionnaires can also

provide

immediate

data validation and can

enforce rules such as select

only one response, or

certain

types of answers such as numerical,

which cannot be done in email

or

with

paper. Other advantages of online

questionnaires include (Lazar

and

Preece,

1999):

� Responses

are usually received

quickly.

� Copying

and postage costs are lower

t h a n for paper surveys or

often

nonexistent.

� Data

can be transferred immediately into a

database for analysis.

� The

time required for data

analysis is reduced.

� Errors

in questionnaire design can be

corrected easily (though it is

better

to avoid

them in the first

place).

397

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

A big

problem with web-based

questionnaires is obtaining a random

sample of

respondents.

Few other disadvantages have

been reported with

online

questionnaires,

but there is some evidence

suggesting that response rates

may be

lower

online than with paper

questionnaires (Witmer et al.,

1999).

Heuristic

evaluation

Heuristic

evaluation is an informal usability

inspection technique developed

by

Jakob

Nielsen and his colleagues

(Nielsen, 1994a) in which

experts, guided by a

set

of usability

principles known as heuristics,

evaluate

whether user-interface

elements,

such as dialog boxes, menus,

navigation structure, online

help, etc.,

conform

to the principles. These

heuristics closely resemble

the high-level design

principles

and guidelines e.g., making

designs consistent, reducing memory

load,

and using

terms that users understand.

When used in evaluation,

they are called

heuristics.

The original set of heuristics

was derived empirically from

an analysis of

249

usability problems (Nielsen,

1994b). We list the latest

here, this time

expanding

them to include some of the

questions addressed when

doing evaluation:

� Visibility

of system status

o Are

users kept informed about

what is going on?

o Is

appropriate feedback provided

within reasonable time about

a

user's

action?

� Match

between system and the

real world

o Is

the language used at the

interface simple?

o Are

the words, phrases and

concepts used familiar to the

user?

� User

control and freedom

o Are

there ways of allowing users

to easily escape from places

they

unexpectedly

find themselves in?

� Consistency

and standards

o Are

the ways of performing

similar actions consistent?

� Help

users recognize, diagnose,

and recover from

errors

o Are

error messages

helpful?

o Do

they use plain language to

describe the nature of the

problem and

suggest a

way of solving it?

� Error

prevention

o Is it

easy to make errors?

o If so

where and why?

� Recognition

rather than recall

o Are

objects, actions and options

always visible?

� Flexibility

and efficiency of use

o Have

accelerators (i.e., shortcuts) been

provided that allow

more

experienced

users to carry out tasks

more quickly?

� Aesthetic

and minimalist design

o Is any

unnecessary and irrelevant information

provided?

� Help

and documentation

o Is

help information provided

that can be easily searched

and easily

followed'.'

398

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

However,

some of these core heuristics

are too general for

evaluating new

products

coming

onto the market and

there is a strong need for

heuristics that are more

closely

tailored

to specific products. For

example, Nielsen (1999)

suggests t h a t the

following

heuristics are more useful

for evaluating commercial websites

and makes

them

memorable by introducing the

acronym HOME RUN:

� High-quality

content

� Often

updated

� Minimal

download time

� Ease

of use

� Relevant

to users' needs

� Unique

to the online medium

� Netcentric

corporate culture

Different

sets of heuristics for evaluating

toys, WAP devices, online

communities,

wearable

computers, and other devices

are needed, so evaluators must develop

their

own by

tailoring Nielsen's heuristics

and by referring to design

guidelines, market

research,

and requirements documents. Exactly

which heuristics are the

best and how

many

are needed are debatable and

depend on the

product.

Using a

set of heuristics, expert

evaluators work with the

product role-playing

typical

users

and noting the problems

they encounter. Although

other numbers of experts

can

be used,

empirical evidence suggests

that five evaluators usually identify

around 75%

of the

total usability

problems.

Asking experts:

walkthroughs

41.4

Walkthroughs

are an alternative approach to

heuristic evaluation for

predicting

users'

problems without doing user

testing. As the name suggests, they

involve

walking

through a task wit h the

system and noting

problematic usability

features.

Most walkthrough techniques do

not involve users. Others,

such as

pluralistic

walkthroughs, involve a team th a t

includes users, developers,

and

usability

specialists.

In this

section we consider cognitive

and pluralistic walkthroughs.

Both were

originally

developed for desktop

systems but can be applied

to web-based systems,

handheld

devices, and products such as

VCRs,

Cognitive

walkthroughs

"Cognitive

walkthroughs involve simulating a

user's problem-solving process

at

each

step in the human-computer

dialog, checking to see if

the user's goals

and

memory

for actions can be assumed

to lead to the next correct

action." (Nielsen and

Mack,

1994, p. 6). The defining

feature is that they focus

on evaluating designs for

ease of

learning--a focus that is

motivated by observations that

users learn by

exploration

(Wharton et al., 1994). The

steps involved in cognitive

walkthroughs are:

1. The characteristics of

typical users are identified

and documented and

sample

tasks are

developed that focus on the

aspects of the design to be

evaluated. A

description

or prototype of the interface to be

developed is also

produced,

along

with a clear sequence of the

actions needed for the users

to complete

the

task.

2. A designer and

one or more expert

evaluators then come together to do

the

analysis.

399

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

evaluators walk through the

action sequences for each

task, placing H

3.

within

the context of a typical scenario, and as

they do this they try

to

answer

the following questions:

Will

the correct action be

sufficiently evident to the

user? (Will the user

�

know

what to do to achieve the

task?)

Will

the user notice that

the correct action is

available? (Can users see

the

�

button or

menu item that they

should use for the

next action? Is it

apparent

when it

is needed?)

Will

the user associate and

interpret the response from

the action

�

correctly?

(Will users know from

the feedback that they

have made a

correct

or incorrect choice of

action?)

In other

words: will users know what

to do, see how to do it,

and understand from

feedback

whether the action was

correct or not?

4. As the

walkthrough is being done, a

record of critical information is

compiled

in

which:

The

assumptions about what would

cause problems and why are

recorded.

�

This

involves explaining why

users would face

difficulties.

Notes

about side issues and

design changes are

made.

�

A summary of

the results is

compiled.

�

The

design is then revised to fix

the problems presented.

5.

It is

important to document the

cognitive walkthrough, keeping

account of what

works

and what doesn't. A

standardized feedback form

can be used in which

answers

are

recorded to the three

bulleted questions in step

(3) above. The form

can also

record

the details outlined in

points 1-4 as well as the

date of the evaluation.

Negative

answers

to any of the questions are

carefully documented on a separate form,

along

with

details of the system, its

version number, the date of

the evaluation, and

the

evaluators'

names. It is also useful to

document the severity of the

problems, for

example,

how likely a problem is to occur and how

serious it will be for

users.

The

strengths of this technique are

that it focuses on users" problems in

detail, yet

users do

not need to be present, nor is a working

prototype necessary. However, it

is

very

time-consuming and laborious to

do. Furthermore the

technique has a

narrow

focus

that can be useful for

certain types of system but

not others.

Pluralistic

walkthroughs

"Pluralistic

walkthroughs are another

type of walkthrough in which

users,

developers

and usability experts work

together to step through a

[task] scenario,

discussing

usability issues associated with dialog

elements involved in

the

scenario

steps" (Nielsen and Mack,

1994. p. 5). Each group of

experts is asked

to assume the

role of typical users. The

walkthroughs are then done

by following

a

sequence of steps (Bias,

1994):

400

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Scenarios

are developed in the form of

a series of hard-copy screens

1.

representing

a single path through the

interface. Often just two or

a few

screens

are developed.

The

scenarios are presented to

the panel of evaluators and

the panelists

2.

are

asked to write down the

sequence of actions they would

take to

move

from one screen to another.

They do this individually

without

conferring

with one another.

3. When everyone has

written down their actions,

the panelists discuss

the

actions

that they suggested for

that round of the review.

Usually, the

representative

users go first so that they

are not influenced by the

other

panel

members and are not

deterred from speaking. Then

the usability

experts

present their findings, and

finally the developers offer

their

comments.

4. Then the panel

moves on to the next round

of screens. This process

continues

until all the scenarios have

been evaluated.

The

benefits of pluralistic walkthroughs

include a strong focus on users'

tasks.

Performance

data is produced and many

designers like the apparent clarity

of

working

with quantitative data. The

approach also lends itself well

to

participatory

design practices by involving a

multidisciplinary team in

which

users

play a key role. Limitations

include having to get all

the experts together

at once

and then proceed at the rate of

the slowest. Furthermore,

only a limited

number of

scenarios, and hence paths

through the interface, can

usually be

explored

because of time constraints.

401

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS