|

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY |

| << EVALUATION – PART VI |

| BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS >> |

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Lecture35

Lecture

35. Evaluation

Part VII

Learning

Goals

The

aim of this lecture is to

understand the strategic

nature of usability

�

The

aim of this lecture is to

understand the nature of the

Web

�

35.1

The relationship

between evaluation and usability?

With

the help of evaluation we

can uncover problems in the

interface that will help

to

improve

the usability of the

product.

Questions

to ask

� Do

you understand the

users?

� Do

you understand the

medium?

� Do

you understand the

technologies?

� Do

you have commitment?

Technologies

� You

must understand the constraints of

technology

� What

can we implement using

current technologies

� Building

a good system requires a

good understanding of

technology

constraints

and potentials

Users

Do you

know your users?

�

What

are their goals and

behaviors?

�

How

can they be

satisfied?

�

Use

goals and personas

�

Commitment

� Building

usable systems requires

commitment?

� Do

you have commitment at every

level in your

organization?

Medium

� You

must understand the medium

that you are working in to

build a good

usable

system

321

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Nature of

the Web Medium

The

World Wide Web is a

combination of many different

mediums of

communication.

Print

(newspapers,

Audio

(radio, CDs,

Video

(TV, movies)

magazines,

books)

etc.)

Traditional

software

applications

It would

be true to say that the

Web is in fact a super

medium which incorporates

all

of the

above media.

Today's

we pages and applications

incorporate elements of the following

media:

� Print

� Video

� Audio

� Software

applications

Because

of its very diverse nature,

the Web is a unique medium

and presents many

challenges

for its designers.

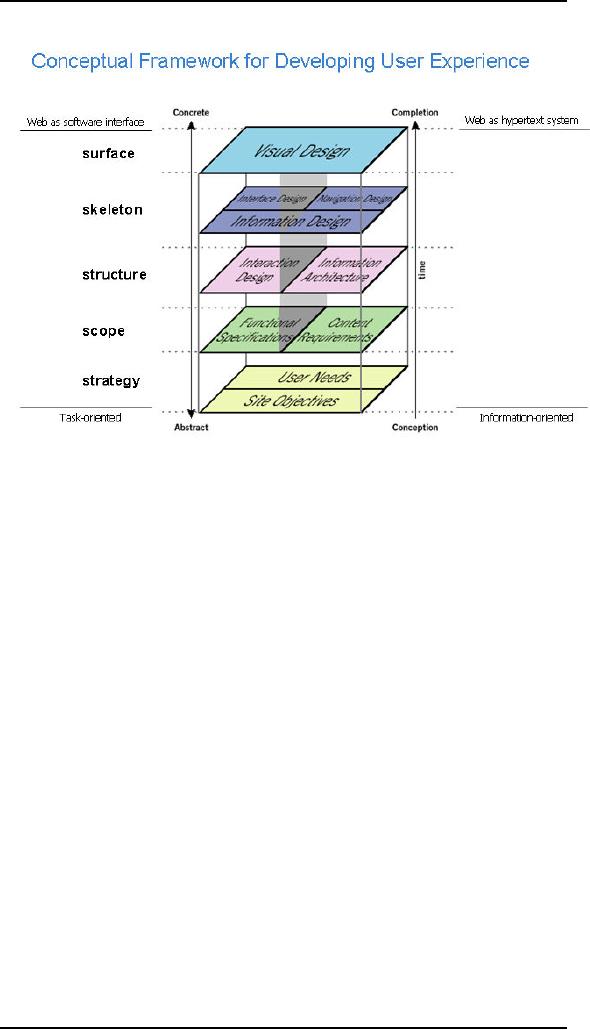

We can

more clearly understand the

nature of the Web by looking

at a conceptual

framework.

322

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

Surface Plane

On the

surface you see a series of

Web pages, made up of images

and text. Some of

these

images are things you can

click on, performing some

sort of function such

as

taking

you to a shopping cart. Some

of these images are just illustrations,

such as a

photograph

of a book cover or the logo

of the site itself.

The

Skeleton Plane

Beneath

that surface is the skeleton of

the site: the placement of

buttons, tabs,

photos,

and

blocks of text. The skeleton

is designed to optimize the

arrangement of these

elements

for maximum effect and

efficiency-so that you remember

the logo and

can

find

that shopping cart button

when you need it.

The

Structure Plane

The

skeleton is a concrete expression of the

more abstract structure of the

site. The

skeleton

might define the placement

of the interface elements on our

checkout page;

the

structure would define how

users got to that page and

where they could go

when

they

were finished there. The

skeleton might define the

arrangement of navigational

items

allowing the users to browse

categories of books; the structure

would define

what

those categories actually were.

The Scope

Plane

The

structure defines the way in

which the various features

and functions of the

site

fit

together. Just what those

features and functions are

constitutes the scope of the

site.

Some

sites that sell books

offer a feature that enables

users to save previously

used

addresses

so they can be used again.

The question of whether that

feature-or any

feature-is

included on a site is a question of

scope.

323

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

Strategy Plane

The

scope is fundamentally determined by

the strategy of the site.

This strategy

incorporates

not only what the

people running the site

want to get out of it but

what

the

users want to get out of

the site as well. In the

case of our bookstore

example,

some of

the strategic objectives are

pretty obvious: Users want to

buy books, and we

want to

sell them. Other objectives

might not be so easy to

articulate.

Building

from Bottom to Top

These

five planes-strategy, scope,

structure, skeleton, and

surface�provide a

conceptual

framework for talking about

user experience problems and

the tools we

use to

solve them.

To

further complicate matters, people will

use the same terms in

dif�ferent ways. One

person

might use "information

design" to refer to what

another knows as

"information

architecture."

And what's the difference

between "interface design"

and "interaction

design?"

Is there one?

Fortunately,

the field of user experience

seems to be moving out of

this Babel-like

state.

Consistency is gradually creeping

into our dis�cussions of these

issues. To

understand

the terms themselves, how

ever, we should look at

where they came

from.

When

the Web started, it was just

about hypertext. People

could create documents,

and

they could link them to

other documents. Tim Berners-Lee,

the inventor of the

Web,

created it as a way for researchers in

the high-energy physics

community, who

were

spread out all over

the world, to share and

refer to each other's findings.

He

knew

the Web had the

potential to be much more

than that, but few

others really

understood

how great its potential

was.

People

originally seized on the Web

as a new publishing medium,

but as technology

advanced

and new features were

added to Web browsers and

Web servers alike,

the

Web

took on new capabilities.

After the Web began to catch on in

the larger Internet

community,

it developed a more complex

and robust feature set

that would enable

Web

sites not only to distribute

information but to collect

and manipulate it as

well.

With

this, the Web became

more interactive, responding to

the input of users in

ways

that

were very much like

traditional desktop

applications.

With

the advent of commercial interests on

the Web, this application

functionality

found a

wide range of uses, such as

electronic commerce, community forums,

and

online

banking, among others.

Meanwhile, the Web continued

to flourish as a

publishing

medium, with countless newspaper and

magazine sites augmenting

the

wave of

Web-only "e-zines" being

published. Technology continued to

advance on

both

fronts as all kinds of sites

made the transition from

static collections of

information

that changed infrequently to dynamic,

database-driven sites that

were

constantly

evolving.

When

the Web user experience

community started to form, its

members spoke two

different

languages. One group saw

every problem as an application

design problem,

and

applied problem-solving approaches from

the traditional desktop and

mainframe

software

worlds. (These, in turn, were

rooted in common practices applied to

creating

all

kinds of products, from cars

to running shoes.) The other

group saw the Web

in

terms of

information distribution and

retrieval, and applied

problem-solving

approaches

from the traditional worlds

of publishing, media, and

information science.

324

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

This

became quite a stumbling

block. Very little progress

could be made when

the

community

could not even agree on basic

terminology. The waters were

further

muddied

by the fact that many

Web sites could not be

neatly categorized as

either

applications

or hypertext information spaces-a

huge number seemed to be a

sort of

hybrid,

incorporating qualities from

each world.

To

address this basic duality

in the nature of the Web,

let's split our five planes

down

the

middle. On the left, we'll

put those elements specific to

using the Web as a

software

interface. On the right,

we'll put the elements

specific to hypertext

information

spaces.

On the

software side, we are mainly

concerned with tasks-the steps involved

in a

process

and how people think

about completing them. Here,

we consider the site as

a

tool or

set of tools that the

user employs to accomplish

one or more tasks. On

the

hypertext

side, our concern is information-what

information the site offers

and what it

means to

our users. Hypertext is

about creating an information

space that users

can

move

through.

The

Elements of User

Experience

Now we

can map that whole

confusing array of terms into

the model. By

breaking

each

plane down into its

component elements, we'll be able to

take a closer look at

how

all the pieces fit

together to create the whole

user experience.

The

Strategy Plane

The

same strategic concerns come

into play for both

software products and

information

spaces. User needs are

the goals for the

site that come from outside

our

organization-specifically

from the people who will

use our site. We must

understand

what

our audience wants from us

and how that fits in

with other goals it

has.

Balanced

against user needs are

our own objectives for

the site. These site

objectives

can be

business goals ("Make $1

million in sales over the

Web this year") or

other

kinds of

goals ("Inform voters about

the candidates in the next

election").

The Scope

Plane

On the

software side, the strategy

is translated into scope

through the creation

of

functional

specifications: a detailed description of

the "feature set" of the

product. On

the

information space side,

scope takes the form of

content requirements: a

description

of the various content elements

that will be

required.

The

Structure Plane

The

scope is given structure on

the software side through

interaction design, in

which

we define

how the system behaves in

response to the user. For

information spaces,

the

structure

is the information architecture:

the arrangement of content elements

within

the

information space.

The

Skeleton Plane

The

skeleton plane breaks down

into three components. On

both sides, we must

address

information design: the

presentation of information in a way

that facilitates

understanding.

For software products, the

skeleton also includes

interface design, or

arranging

interface elements to enable users to

interact with the

functionality of the

system.

The interface for an

information space is its

navigation design: the set

of

screen

elements that allow the user

to move through the

information architecture.

The

Surface Plane

Finally,

we have the surface. Regardless of

whether we are dealing with a

software

product

or an information space, our

concern here is the same:

the visual design, or

the

look of the finished

product.

325

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Using

the Elements

Few

sites fall exclusively on

one side of this model or

the other. Within each

plane,

the

elements must work together to accomplish

that plane's goals. For

example,

information

design, navigation design,

and interface design jointly

define the skeleton

of a

site. The effects of

decisions you make about

one element from all

other elements

on the

plane is very difficult. All

the elements on every plane

have a common

Function-in

this example, defining the

site's skeleton-even if they

perform that

function

in different ways.elements on the

plane is very difficult. All

the elements on

every

plane have a common

function-in this example,

defining the site's

skeleton-even

if they

perform that function in

different ways.

This

model, divided up into neat

boxes and planes, is a convenient

way to think about

user

experience problems. In reality,

however, the lines between

these areas are not

so

clearly

drawn. Frequently, it can be

difficult to identify whether a

particular user

experience

problem is best solved

through attention to one

element instead of

another.

Can a

change to the visual design do

the trick, or will the

underlying navigation

design

have to be reworked? Some

problems require attention in

several areas at once,

and

some seem to straddle the

borders identified in this

model.

The

way organizations often

delegate responsibility for

user experience issues

only

complicates

matters further. In some organizations,

you will encounter people

with

job

titles like information

architect or interface designer.

Don't be confused by

this.

These

people generally have

expertise spanning many of

the elements of user

experience,

not just the specialty

indicated by their title.

It's not necessary for

thinking

about

each of these issues.

A couple

of additional factors go into

shaping the final user

experience that you

won't

find

covered in detail here. The

first of these is content.

The old saying (well,

old in

Web

years) is that "content is king" on

the Web. This is absolutely

true-the single

most

important thing most Web

sites can offer to their

users is content that those

users

will find

valuable.

326

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS