|

EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION |

| << EVALUATION |

| EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST >> |

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Lecture

32

Lecture

32. Evaluation

IV

Learning

Goals

As the

aim of this lecture is to

introduce you the study of

Human Computer

Interaction,

so that after studying this

you will be able to:

� Understand

the significance of

navigation

People

won't use your Web site if

they can't find their way

around it.

You

know this from your

own experience as a Web

user. If you go to a site

and can't

find

what you're looking for or

figure out how the

site is organized, you're

not likely

to stay

long--or come back. So how

do you create the proverbial

"clear, simple, and

consistent"

navigation?

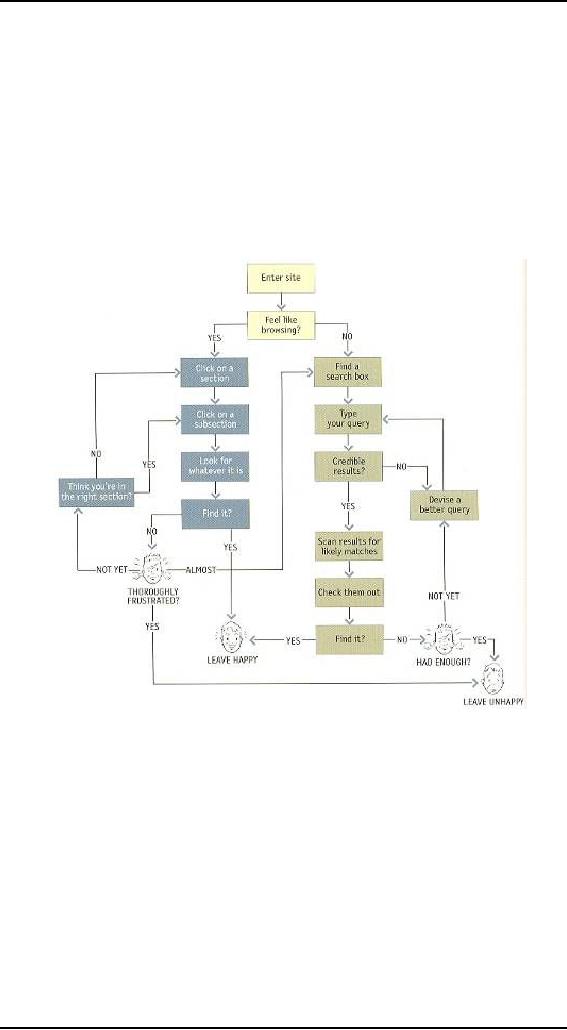

Scene

from a mall

32.1

Picture

this: It's Saturday

afternoon and you're headed

for the mall to buy a

chainsaw.

As you

walk through the door at

Sears, you're thinking,

"Hmmm. Where do they

keep

chainsaws?"

As soon as you're inside, you start

looking at the department

names, high

up on the

walls. (They're big enough

that you can read

them from all the

way across

the

store.)

"Hmmm,"

you think, 'Tools? Or Lawn

and Garden?" Given that

Sears is so heavily

tool-oriented,

you head in the direction of

Tools.

When

you reach the Tools

department, you start looking at

the signs at the end of

each

aisle.

294

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

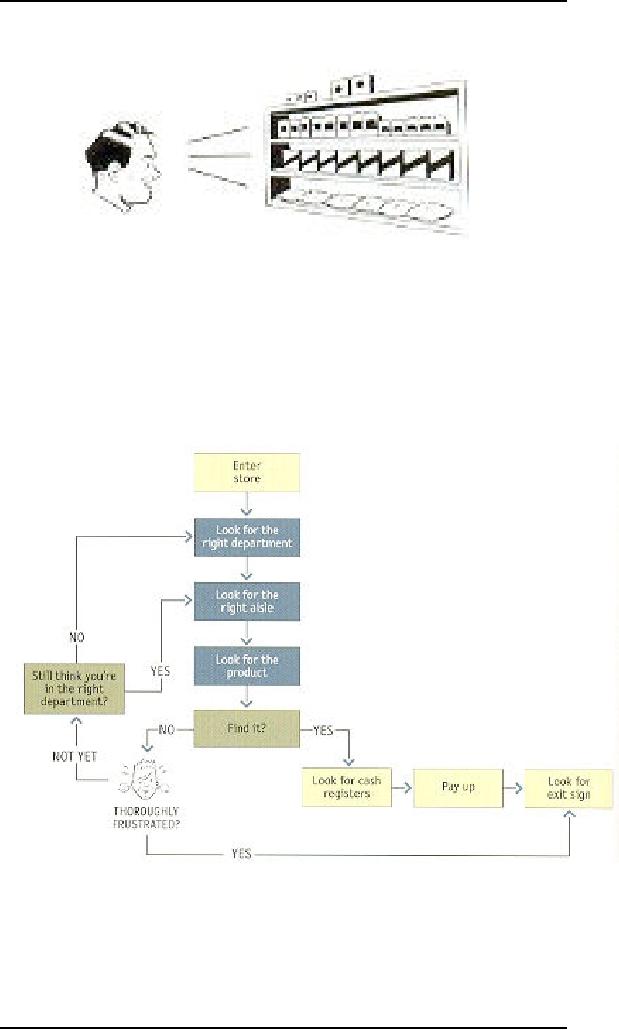

When you

think you've got the

right aisle, you start

looking at the individual

products.

If it rums

out you've guessed wrong,

you try another aisle, or

you may back up

and

start

over again in the Lawn

and Garden department. By

the time you're done,

the

process

looks something like

this:

Basically,

you use the store's

navigation systems (the signs

and the organizing

hierarchy

that the signs embody) and

your ability to scan shelves

full of products to

find

what you're looking

for.

295

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

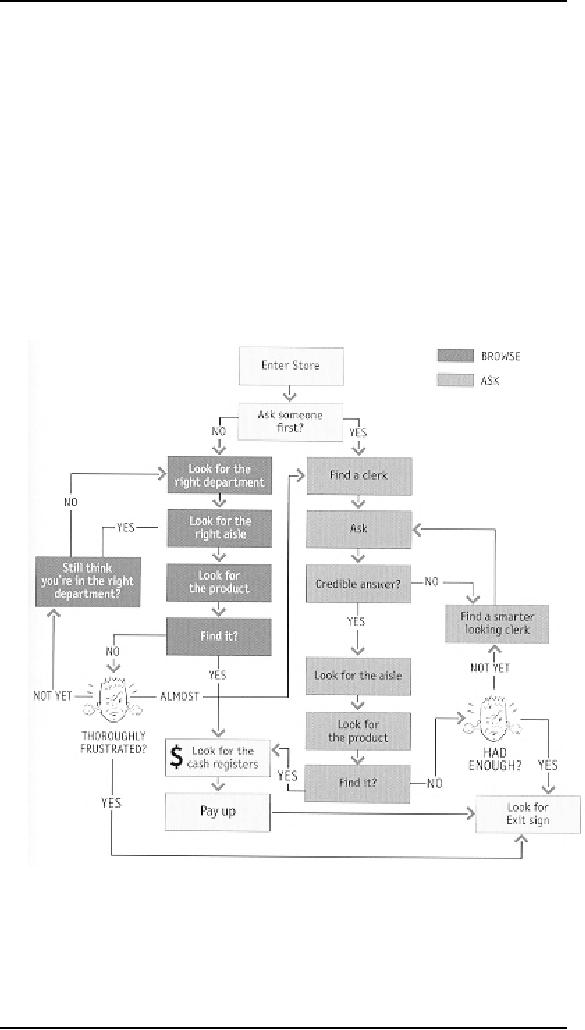

Of

course, the actual process is a little

more complex. For one thing, as

you walk in the

door

you usually devote a few

microseconds to a crucial decision:

Are you going to

start

by

looking for chainsaws on

your own or are you

going to ask someone where

they are?

It's a

decision based on a number of

variables--how familiar you

are with the store,

how

much you trust their

ability to organize things

sensibly, how much of a

hurry

you're

in, and even how sociable

you are.

When we

factor this decision in,

the process looks something

like shown in figure

on

next

page:

Notice

that even if you start

looking on your own, if

things don't pan out there's

a

good

chance that eventually

you'll end up asking someone

for directions

anyway.

Web

Navigation

32.2

In many

ways, you go through the

same process when you

enter a Web site.

� You're

usually trying to find

something.

296

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

In the

"real" world it might be the

emergency room or a can of

baked beans. On

the

Web, it might be the

cheapest 4-head VCR with

Commercial Advance or

the

name of

the actor in Casablanca who

played the headwaiter at

Rick's.

�

You

decide whether to ask first

or browse first.

The

difference is that on a Web site there's no one

standing around who can

tell

you

where things are. The Web

equivalent of asking directions is

searching--

typing a

description of what you're looking

for in a search box and

getting back a

list of

links to places where it might

be.

Some

people (Jakob Nielsen calls

them "search-dominant" users) will

almost always

look

for a search box as soon as

they enter a site. (These

may be the same people

who

look

for the nearest clerk as

soon as they enter a

store.)

Other

people (Nielsen's "link-dominant"

users) will almost always

browse first,

searching

only when they've run

out of likely links to click

or when they have

gotten

sufficiently

frustrated by the site.

For

everyone else, the decision

whether to start by browsing or searching

depends on

their

current frame of mind, how

much of a hurry they're in,

and whether the

site

appears

to have decent, browsable

navigation.

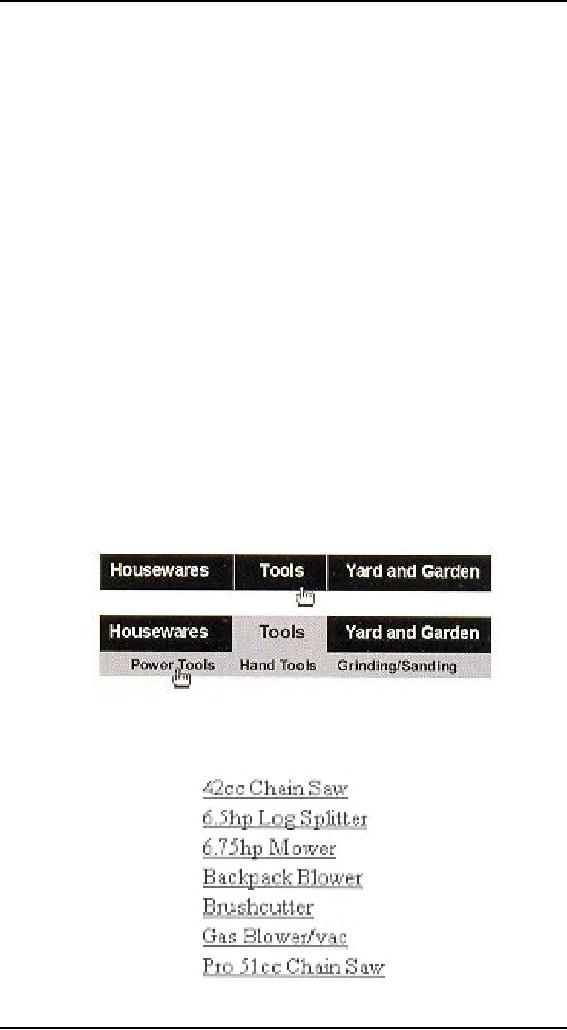

� If

you choose to browse, you

make your way through a

hierarchy, using

signs to

guide you.

Typically

you'll look around on the

Home page for a list of

the site's main

sections

(like

the store's department signs)

and elide on the one

that seems right.

Then

you will choose from the

list of subsections.

With

any luck, after another

click or two you'll end up

with a list of the kind of

thing

you're

looking for:

297

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Then

you can click on the

individual links to examine

them in detail, the same

way

you'd

take products off the

shelf and read the

labels.

�

Eventually,

if you can't find what

you're looking for, you'll

leave.

This is

as true on a Web site as it is at

Sears. You'll leave when

you're

convinced

they haven't got it, or

when you're just too

frustrated to keep

looking.

Here is

what the process looks

like:

The

unbearable lightness of

browsing

Looking

for things on a Web site

and looking for them in

the "real" world have a

lot

of

similarities. When we're

exploring the Web, in some

ways it even feels like

we're

moving

around in a physical space.

Think of the words we use to

describe the

experience--like

"cruising," "browsing," and

"surfing." And clicking a

link doesn't

"load" or

"display" another page--it "takes

you to" a page.

But the

Web experience is missing many of the

cues we've relied on all

our lives to

negotiate

spaces. Consider these oddities of

Web space:

No sense

of scale.

Even

after we've used a Web

site extensively, unless it's a

very small site we tend

to

have

very little sense of how

big it is (50 pages? 1,000?

17,000?). For all we

know,

there

could be huge corners we've

never explored. Compare this to a

magazine, a

298

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

museum,

or a department store, where

you always have at least a

rough sense of the

seen/unseen

ratio.

The

practical result is that

it's very hard to know

whether you've seen

everything of

interest

in a site, which means it's

hard to know when to stop

looking.

No sense

of direction.

In a Web

site, there's no left and

right, no up and down. We

may talk about moving

up

and

down, but we mean up and

down hi the hierarchy--to a more general

or more

specific

level.

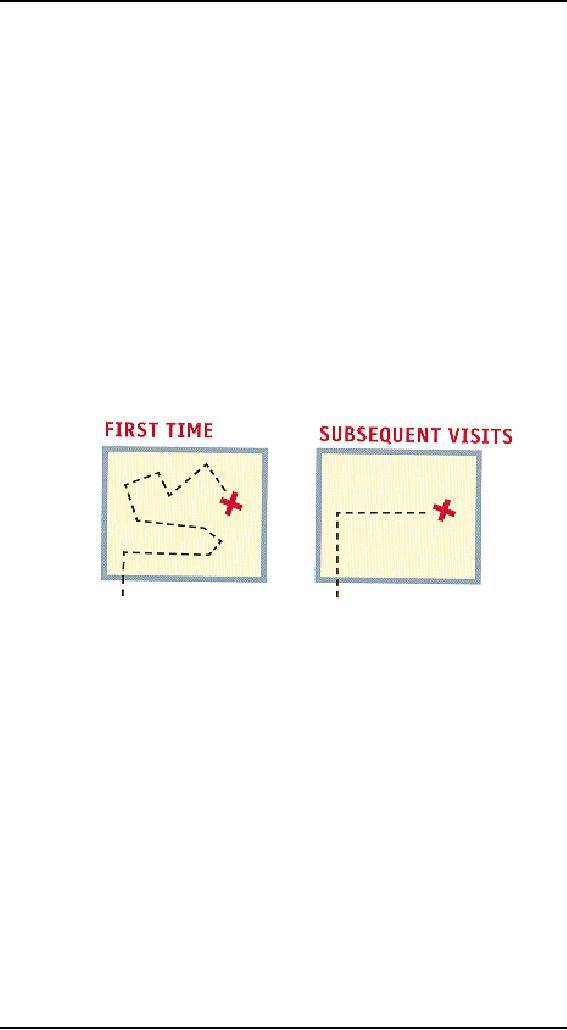

No sense

of location.

In

physical spaces, as we move

around we accumulate knowledge

about the space.

We

develop a sense of where

things are and can

take shortcuts to get to

them.

We may

get to the chainsaws the

first time by following the

signs, but the next

time

we're

just as likely to

think,

"Chainsaws?

Oh, yeah, I remember where

they were: right rear

corner,

near

the refrigerators."

And

then head straight to

them.

But on

the Web, your feet

never touch the ground;

instead, you make your way

around

by

clicking on links. Click on

"Power Tools" and you're

suddenly teleported to

the

Power

Tools aisle with no

traversal of space, no glancing at

things along the

way.

When we

want to return to something on a

Web site, instead of relying

on a physical

sense of

where it is we have to remember

where it is in the conceptual

hierarchy and

retrace

our steps.

This is

one reason why

bookmarks--stored personal shortcuts--are

so important, and

why

the Back button accounts

for somewhere between 30 and 40

percent of all Web

clicks.

It also

explains why the concept of

Home pages is so important.

Home pages are--

comparatively--fixed

places. When you're in a

site, the Home page is like

the North

Star.

Being able to click Home

gives you a fresh

start.

This

lack of physicality is both

good and bad. On the

plus side, the sense

of

weightlessness

can be exhilarating, and

partly explains why it's so

easy to lose track

of time

on the Web--the same as when

we're "lost" in a good

book.

On the

negative side, I think it

explains why we use the

term "Web navigation"

even

though we

never talk about "department

store navigation" or "library

navigation." If

you

look up navigation

in a

dictionary, it's about doing

two things: getting from

one

place to

another, and figuring out

where you are.

299

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

We talk

about Web navigation because

"figuring out where you

are" is a much more

pervasive

problem on the Web than in

physical spaces. We're

inherently-lost when

we're on

the Web, arid we can't peek

over the aisles to see where

we are. Web

navigation

compensates for this missing

sense of place by embodying

the site's

hierarchy,

creating a sense of

"there."

Navigation

isn't just a feature

of a

Web site; it is the Web site, in the

same way that the

building,

the shelves, and die cash

registers are

Sears.

Without it, there's no there

there.

The

moral? Web navigation had

better be good.

The

overlooked purposes of

navigation

Two of

the purposes of navigation

are fairly obvious: to help

us find whatever it is

we're

looking for, and to tell us

where we are.

And

we've just talked about a

third:

It gives

us something to hold on

to.

As a

rule, it's no fun feeling

lost. (Would you rather

"feel lost" or "know your

way

around?"}

Done right, navigation puts

ground under our feet

(even if it's virtual

ground)

and gives us handrails to

hold on to-- to make us feel

grounded.

But

navigation has some other

equally important--and easily

overlooked--functions:

It tells

us what's here.

By making

the hierarchy visible,

navigation tells us what the

site contains.

Navigation

reveals

content! And revealing the

site may be even more

important than guiding

or

situating

us.

It tells

us how to use the

site.

If the

navigation is doing its job,

it tells you implicitly

where to

begin and what

your

options

are. Done correctly, it

should be all the

instructions you need.

(Which is good,

since most

users will ignore any other

instructions anyway.)

It gives

us confidence in the people

who built it.

Every

moment we're in a Web site,

we're keeping a mental

running tally: "Do

these

guys

know what they're doing?"

It's one of the main

factors we use in

deciding

whether

to bail out and deciding

whether to ever come back.

Clear, well-thought-out

navigation

is one of the best

opportunities a site has to

create a good

impression.

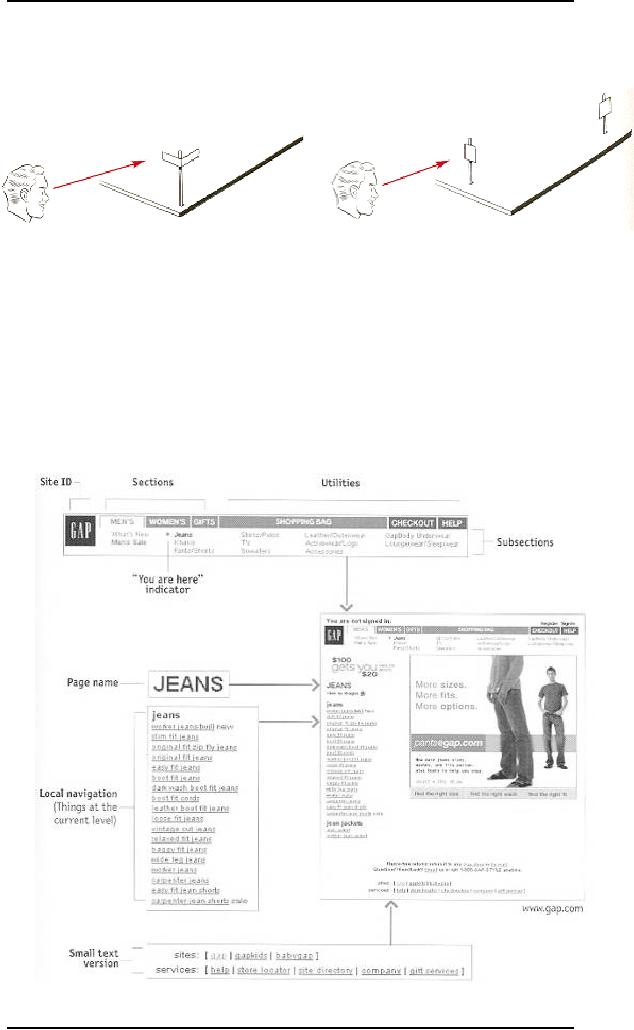

Web

navigation conventions

Physical

spaces like cities and

buildings (and even

information spaces like

books and

magazines)

have their own navigation

systems, with conventions

that have evolved

over

time like street signs, page numbers,

and chapter titles. The

conventions specify

(loosely)

the appearance and location of

the navigation elements so we know

what to

look

for and where to look

when we need them.

Putting

them in a standard place lets us locate

them quickly, with a minimum

of effort;

standardizing

their appearance makes it

easy to distinguish them

from everything else.

For

instance, we expect to find street

signs at street corners, we expect to

find them by

looking

up (not down), and we expect

them to look like street signs

(horizontal, not

vertical).

300

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

We also

take it for granted that the

name of a building will be above or

next to its front

door. In

a grocery store, we expect to find

signs near the ends of each

aisle. In a

magazine,

we know there will be a

table of contents somewhere in the

first few pages and

page

numbers somewhere in the margin of

each page--and that they'll

look like a table of

contents

and page numbers.

Think of

how frustrating it is when

one of these conventions is

broken (when

magazines

don't put page numbers on advertising

pages, for instance).

Navigation

conventions for the Web

have emerged quickly, mostly adapted

from

existing

print conventions. They'll

continue to evolve, but for

the moment these are

the basic

elements:

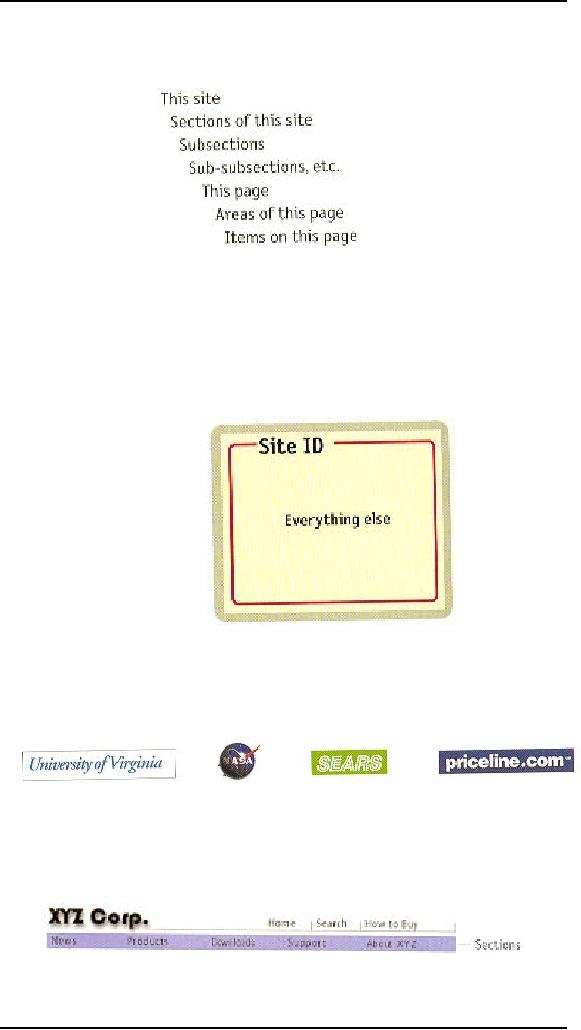

301

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Don't

look now, but it's following

us

Web

designers use the term penitent

navigation (or

global

navigation) to describe

the

set of

navigation elements that appear on every

page of a site.

Done

right, persistent navigation

should say--preferably in a calm,

comforting voice:

"The

navigation is over here.

Some parts will change a little depending

on where you

are, but

it will always be here, and it will

always work the same

way."

Just

having the navigation appear in

the same place on every page

with a consistent

look

gives you instant

confirmation that you're

still in the same

site--which is more

important

than you might think.

And keeping it the same

throughout the site means

that

(hopefully)

you only have to figure

out how it works

once.

Persistent

navigation should include

the five elements you most need to

have on

hand at

all times.

We'll

look at each of them in a

minute. But first...

Some

Exceptions

There are

two exceptions to the

"follow me everywhere"

rule:

The

Home page.

The

Home page is not like the

other pages--it has

different burdens to bear,

different

promises to

keep. As we'll see in the

next chapter, this sometimes

means that it makes

sense

not to use the persistent

navigation there.

Forms.

On pages

where a form needs to be

filled in, the persistent

navigation can sometimes

be an

unnecessary distraction. For

instance, when I'm paying

for my purchases on an

e-commerce

site you don't really

want me to do anything but

finish filling in the

forms.

The same is true when I'm

registering, giving feedback, or

checking off

personalization

preferences.

For

these pages, it's useful to

have a minimal version of

the persistent

navigation

with

just the Site ID, a link to

Home, and any Utilities

that might help me fill out

the

form.

Site

ID

The

Site ID or logo is like the

building name for a Web

site. At Sears, I really

only

need to

see the name on my way

in; once I'm inside, I know

I'm

still in Sears until

I

leave.

But on the Web--where my

primary mode of travel is

teleportation--I need to

see it on

every page.

In the

same way that we expect to

see the name of a building

over the front

entrance,

we expect

to see the Site ID at the

top of the page--usually in

(or at least near]

the

upper

left corner/

Why?

Because the Site ID

represents the whole site,

which means it's the

highest

thing in

the logical hierarchy of the

site.

302

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

And

there are two ways to get

this primacy across in the

visual hierarchy of the

page:

either

make it the most prominent

thing on the page, or make it

frame everything

else.

Since

you don't want the ID to be

the most prominent element on the

page (except,

perhaps,

on the Home page), the

best place for it--the

place that is least likely to

make me

think--is

at the top, where it frames

the entire page.

And in

addition to being where we

would expect it to be, the

Site ID also needs to look

like

a

Site

ID. This means it should

have the attributes we would

expect to see in a

brand

logo or the sign outside a

store: a distinctive typeface, and a

graphic that's

recognizable

at any size from a button to

a billboard.

The

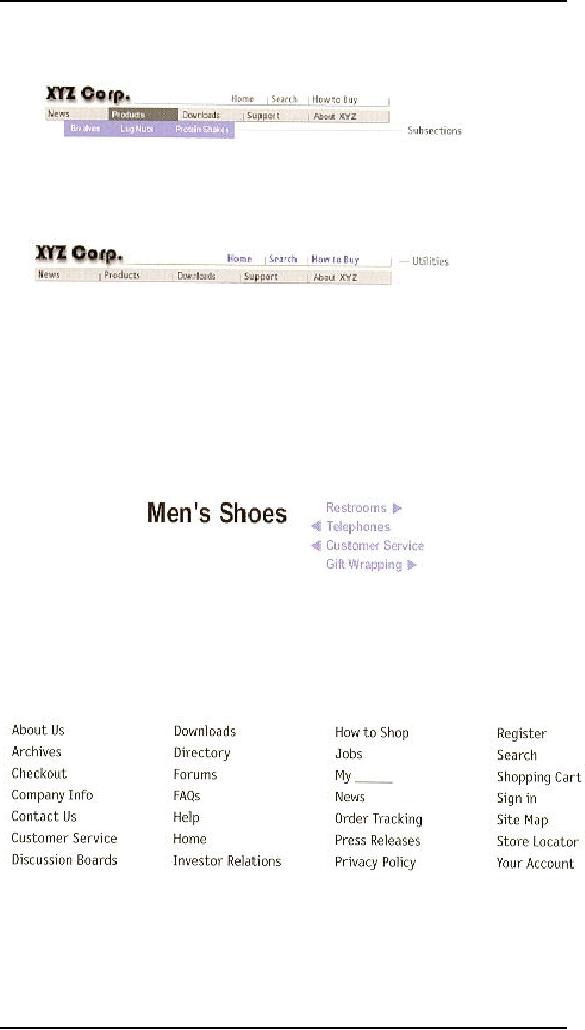

Sections

The

Sections--sometimes called the

primary

navigation--are

the links to the

main

sections of

the site: the fop

level of the site's

hierarchy

303

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

In most

cases, the persistent navigation

will also include space to

display the secondary

navigation:

the list of subsections in the

current section.

The

Utilities

Utilities

are the links to important

elements of the site that

aren't reajiy part of

the

content

hierarchy.

These are

things that either can

help me use the site

(like Help, a Site Map, or

a

Shopping

Cart} or can provide

information about its

publisher (like About Us

arid

Contact

Us).

Like

the signs for the facilities

in a store, the Utilities list

should be slightly less

prominent

than the Sections.

Utilities

will vary for different

types of sites. For a

corporate or e-commerce site,

for

example,

they might include any of

the following:

As a

rule, the persistent navigation

can accommodate only four or

five Utilities--the

tend to

get lost in the crowd.

The less frequently used

leftovers can be

grouped

together

on the Home page.

304

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

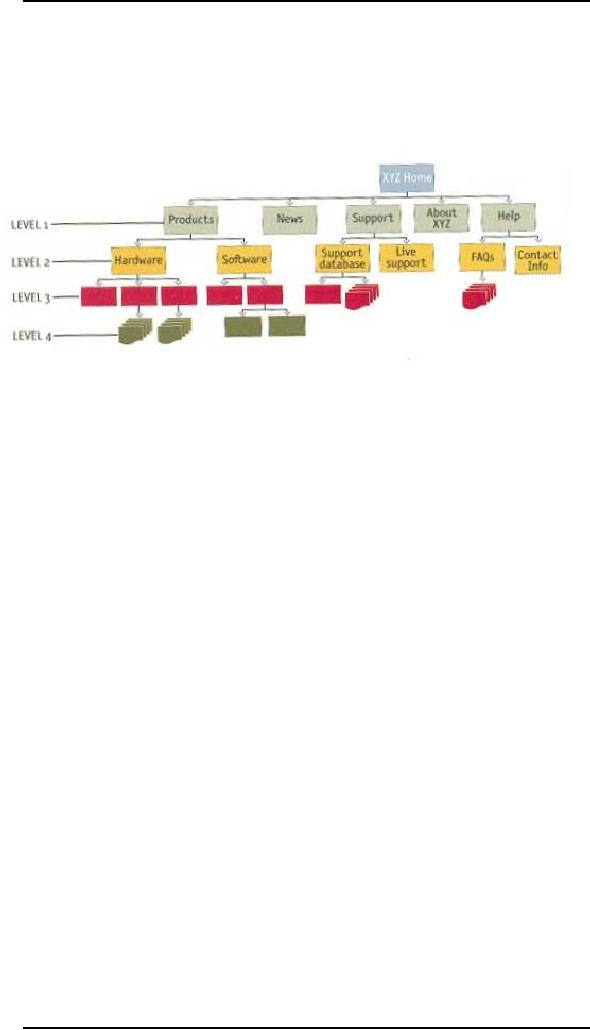

Low Level

Navigation

It's

happened so often I've come to

expect it: When designers I

haven't worked with

before

send me preliminary page designs so I can

check for usability issues.

I almost

inevitably

get a flowchart that shows a

site four levels deep...

...and

sample pages for the Home

page and the top

two

levels.

I keep

flipping the pages looking

for more, or at least for

the place where

they've

scrawled,

"Some magic happens here,"

but I never find even

that. I think this is one

of

the most

common problems in Web

design (especially in larger sites):

failing to give

the

lower-level navigation the

same attention as the top.

In so many sites, as soon as

you

get past the second

level, the navigation breaks

down and becomes ad hoc.

The

problem

is so common that it's

actually hard to find good

examples of third-level

navigation.

Why

does this happen?

Partly,

because good multi-level

navigation is just plain

hard to figure out-- given

the

limited

amount of space on the page,

and the number of elements

that have to be

squeezed

in.

Partly

because designers usually don't

even have enough time to

figure out the first

two

levels.

Partly

because it just doesn't seem

that important. (After all,

how important can it

be?

It's

not primary. It's not

even secondary.) And there's a

tendency to think that by

the

time

people get that far

into the site, they'll

understand how it works.

And

then there's the problem of

getting sample content and

hierarchy examples

for

lower-level

pages. Even if designers

ask, they probably won't get

them, because the

people

responsible for the content

usually haven't thought

things through that

far,

either.

But

the reality is that users

usually end up spending as

much time on

lower-level

pages as

they do at the top. And

unless you've worked out

top-to-bottom navigation

from

the beginning, it's very

hard to graft it on later

and come up with

something

consistent.

The

moral? It's vital to have

sample pages that show the

navigation for all

the

potential

levels of the site before

you start arguing about the

color scheme for

the

Home

page.

305

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

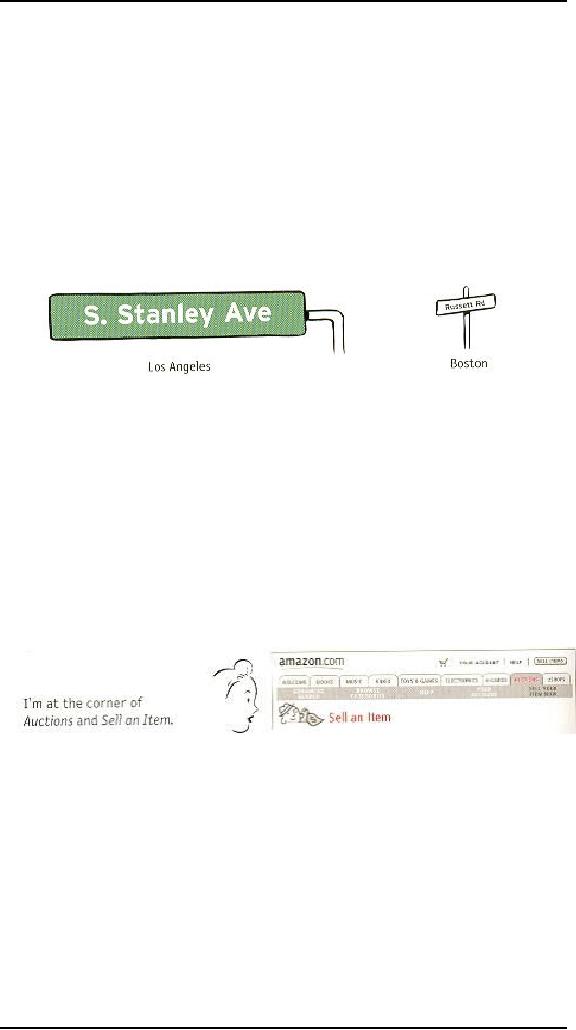

Page

names

If you've

ever spent time in Los

Angeles, you understand that

it's not just a song

lyric--L.A.

really is a great big freeway.

And because people in LA.

take driving

seriously,

they have the best street

signs I've ever seen. In

L.A.,

� Street

signs are big. When you're

stopped at an intersection, you

can read the

sign

for the next cross

street.

� They're

in the right place--hanging ovsr

the

street you're driving on, so

all

you

have to do is glance

up.

Now,

I'll admit I'm a sucker for

this kind of treatment

because I come from

Boston,

where

you consider yourself lucky

if you can manage to read the street

sign while

there's

still time to make the

turn.

The

result? When I'm driving in

LA., I devote

less energy and attention to

dealing

with

where I am and more to

traffic, conversation, and

listening to All

Things

Considered.

Page

names are the street signs of

the Web. Just as with street

signs, when things are

going

well I may not notice page

names at all. But as soon as I start to

sense that I

may

not be headed in the right

direction, I need to be able to spot the

page name

effortlessly

so I can get my

bearings.

There

are four things you need to

know about page

names:

� Every

page needs a name. Just as

every corner should have a

street sign, every

page

should have a name.

Designers

sometimes think, "Well, we've

highlighted the page name in

the

navigation.

That's good enough." It's a

tempting idea because it can

save space, and

it's

one less element to work

into the page layout, but

it's not enough. You need

a

page name,

too.

The

name needs to be in the

right place. In the

visual hierarchy of the

page,

�

the page

name should appear to be framing

the content that is unique

to this

page.

(After all, that's what it's

naming--not the navigation or

the ads, which

are

just the

infrastructure.)

306

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

name needs to be prominent. You

want the combination of

position,

�

size,

color, an d typeface to make

the name say "This is the

heading for the

entire

page." In most cases, it will be

the largest text on the

page.

The

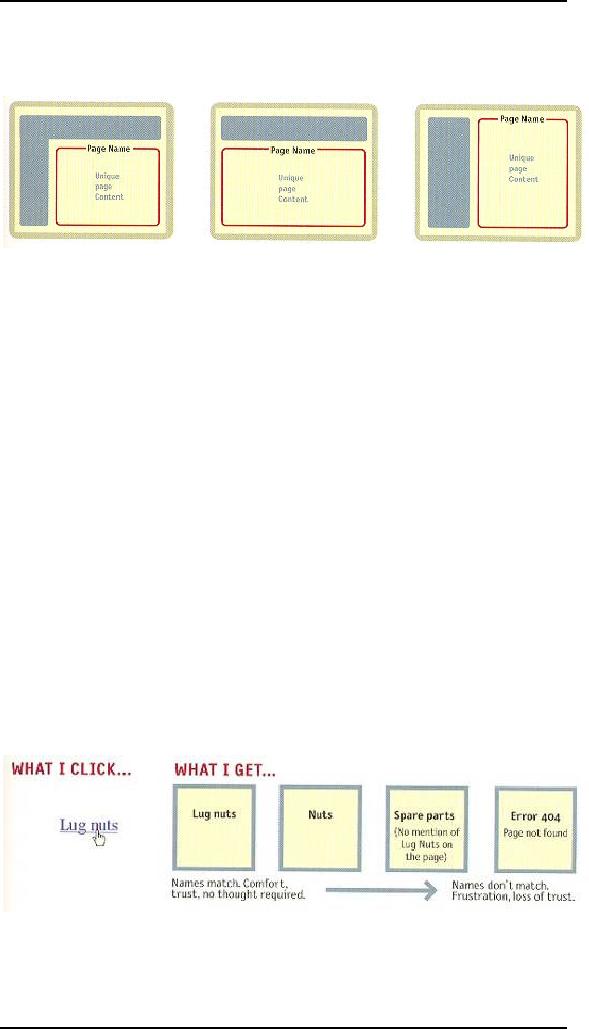

name needs to match what I

clicked. Even

though nobody ever

�

mentions

it, every site makes an

implicit social contract with its

visitors:

In other

words, if" I click on a link or button

that says "Hot mashed

potatoes,"

the

site will take me to a page named "Hot

mashed potatoes."

It may

seem trivial, but it's

actually a crucial agreement.

Each time a site

violates

it, I'm

forced to think, even if

only for milliseconds, "Why

are those two things

different?"

And if there's a major discrepancy

between the link name and

the

page

name or a lot of minor discrepancies, my

trust in the site--and

the

competence

of the people who publish

it--will be diminished.

Of

course, sometimes you have to compromise,

usually because of space

limitations. If

the

words I click on and the

page name don't match

exactly, the important thing

is

that

(a)

they match as closely as

possible, and (b) the

reason for the difference is

obvious.

For

instance, at Gap.com if I dick

the buttons labeled "Gifts

for Him" and "Gifts

for

Her," I

get pages named "gifts for

men" and "gifts for

women." The wording

isn't

identical,

but they feel so equivalent

that I'm not even

tempted to think about

the

difference.

307

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

"You

are here"

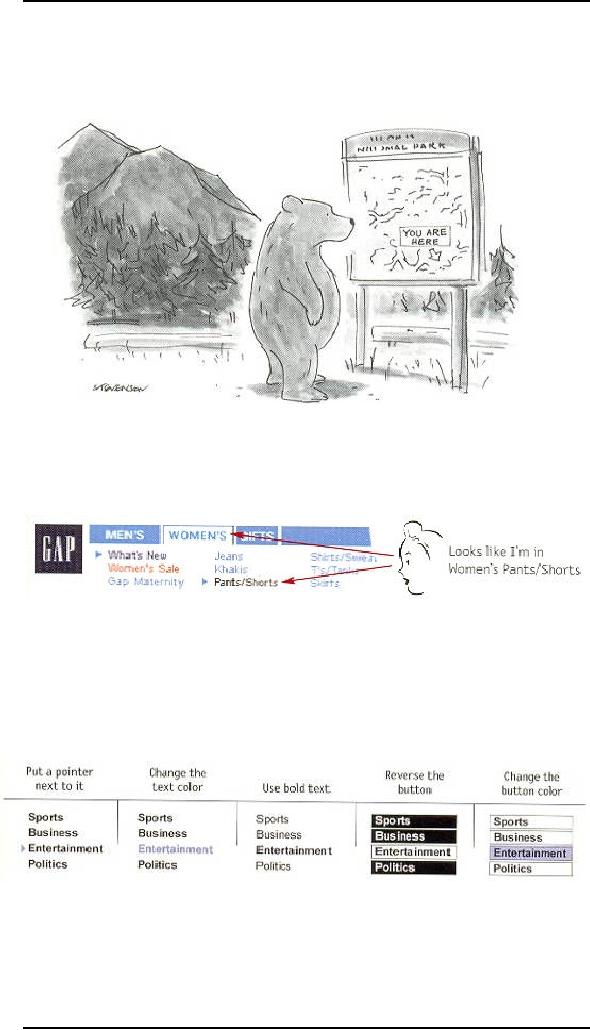

One of

the ways navigation can counteract the

Web's inherent "lost in

space" feeling is by

showing

me where I am in the scheme of

things, the same way

that a "You are

here"

indicator

does on the map in a shopping

mall--or a National

Park.

On the

Web, this is accomplished by

highlighting my current location in

whatever

navigational

bars, lists, or menus appear on

the page.

In this

example, the current section

(Women's) and subsection

(Pants/Shorts) have

both been

"marked." There are a number

of ways to make the current

location stand

out:

The most

common failing of "You are

here" indicators is that

they're too subtle.

They

need to

stand out; if they don't,

they lose their value as

visual cues and end up

just

adding

more noise to the page. One way to

ensure that they stand

out is to apply more

than one

visual distinction--for instance, a

different color and

bold

text.

308

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Breadcrumbs

Like

"You are here" indicators,

Breadcrumbs show you where

you are. (Sometimes

they

even include the words

"You are here.")

They're

called Breadcrumbs because

they're reminiscent of the

trail of crumbs Hansel

dropped

in the woods so he and

Gretel could End their

way back home.

Unlike

"You are here" indicators,

which show you where you

are in the context of

the

site's

hierarchy, Breadcrumbs only

show you the path

from the Home page to

where

you

are. (One shows you

where you are in the

overall scheme of things,

the other shows

you

how to get there--kind of

like the difference between

looking at a road map and

looking

at a set of turn-by-turn directions.

The directions can be very

useful, but you

can

learn more from the

map.)

You

could argue that bookmarks

are more like the fairy tale

breadcrumbs, since we

drop

them as

we wander, in anticipation of possibly

wanting to retrace our steps

someday.

Or you

could say that visited

links (links that have changed

color to show that

you've

clicked

on them) are more like

breadcrumbs since they mark

the paths we've

taken,

and if we

don't revisit them soon

enough, our browser (like

the birds) will

swallow

them

up.

309

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS