|

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Lecture

26

Lecture

26. Behavior

& Form Part I

Learning

Goals

As the

aim of this lecture is to

introduce you the study of

Human Computer

Interaction,

so that after studying this

you will be able to:

� Understand

the narratives and

scenarios

� Define

requirements using persona-based

design

Software

Posture

26.1

Most

people have a predominant

behavioral stance that fits

their working role on

the

job:

The soldier is wary and

alert; the toll-collector is

bored and disinterested;

the

actor is

flamboyant and bigger than

life; the service

representative is upbeat

and

helpful.

Programs, too, have a predominant

manner of presenting themselves to

the

user.

A program

may be bold or timid,

colorful or drab, but it

should be so for a

specific,

goal-directed

reason. Its manner shouldn't

result from the personal

preference of its

designer

or programmer. The presentation of

the program affects the

way the user

relates to

it, and this relationship

strongly influences the

usability of the

product.

Programs whose

appearance and behavior conflict

with their purposes will

seem

jarring

and inappropriate, like fur

in a teacup or a clown at a wedding.

I

The

look and behavior of your

program should reflect how

it is used, rather than

an

arbitrary

standard. A program's behavioral

stance -- the way it

presents itself to

the

user --

is its posture. The look

and feel of your program

from the perspective

of

posture

is not

an

aesthetic choice: It is a behavioral

choice. Your program's

posture is

its

behavioral foundation, and

whatever aesthetic choices you make

should be in

harmony

with this posture.

The

posture of your interface

tells you much about

its behavioral stance,

which, in

turn,

dictates many of the

important guidelines for the

rest of the design. As

an

interaction

designer, one of your first

design concerns should be ensuring

that your

interface

presents the posture that is

most appropriate for its

behavior and that of

your

users.

This lecture explores the

different postures for applications on

the desktop.

Postures for the

Desktop

26.2

Desktop

applications fit into four

categories of posture: sovereign,

transient,

daemonic,

and auxiliary. Because each

describes a different set of

behavioral

attributes,

each also describes a

different type of user

interaction. More

importantly,

these

categories give the designer a

point of departure for

designing an interface. A

sovereign

posture program, for

example, won't feel right

unless it behaves in a

"sovereign"

way. Web and other

non-desktop applications have

their own variations

of

posture.

234

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Sovereign

posture

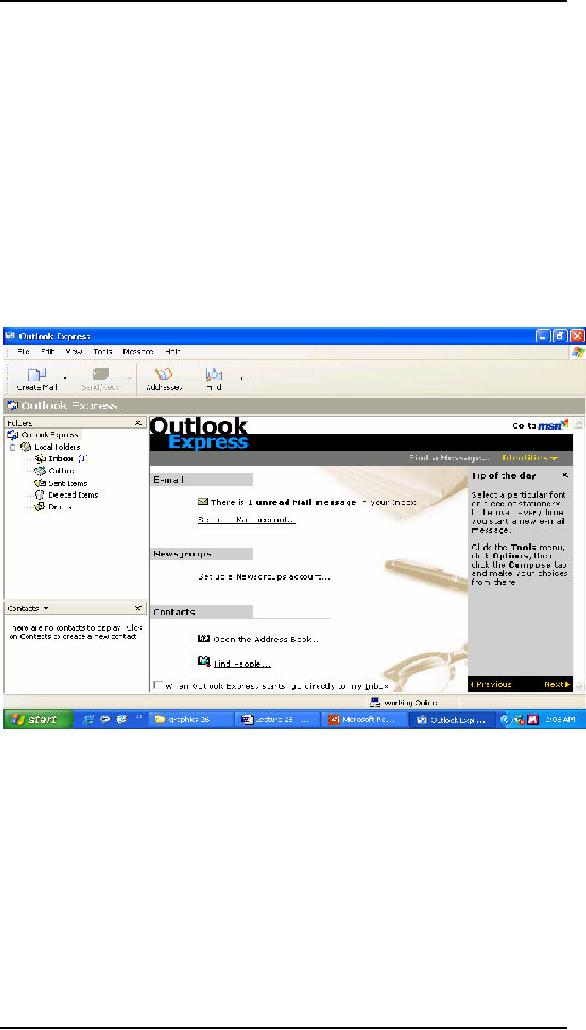

Programs

that are best used

full-screen, monopolizing the

user's attention for

long

periods

of time, are sovereign

posture application. Sovereign

applications offer a

large

set of

related functions and

features, and users tend to

keep them up and

running

continuously.

Good examples of this type

of application are word

processors,

spreadsheets,

and e-mail applications.

Many vertical applications

are also sovereign

applications

because they often deploy on

the screen for long

periods of time, and

interaction

with them can be very

complex and involved. Users

working with

sovereign

programs often find themselves in a

state of flow. Sovereign

programs are

usually

used maximized. For example, it is hard to

imagine using Outlook in a

3x4 inch

window --

at that size it's not

really appropriate for its

main job: creating and

viewing

e-mail

and appointments (see

Figure).

Sovereign

programs are characteristically used

for long, continuous

stretches of time.

A

sovereign program dominates a

user's workflow as his

primary tool.

PowerPoint,

for

example, is open full screen

while you create a

presentation from start to

finish.

Even if

other programs are used for

support tasks, PowerPoint

maintains its

sovereign

stance.

The

implications of sovereign behavior are

subtle, but quite clear

after you think

about

them. The most important

implication is that users of

sovereign programs

are

intermediate

users. Each user spends time

as a novice, but only a

short period of time

relative

to the amount of time he

will eventually spend using

the product. Certainly

a

new

user has to get over

the painful hump of an

initial learning curve, but

seen from

the

perspective of the entire

relationship of the user

with the application, the

time he

spends

getting acquainted with the

program is small.

235

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

From

the designer's point of view,

this means that the

program should be designed

for

optimal

use by perpetual intermediates

and not be aimed primarily

for beginners (or

experts).

Sacrificing speed and power

in favor of a clumsier but

easier-to-learn idiom

is out of

place here, as is providing only

nerdy power tools. Of

course, if you can

offer

easier

idioms without compromising

the interaction for

intermediate users; that

is

always

best.

Between

first-time users and

intermediate users there are

many people who

use

sovereign

applications only on occasion.

These infrequent users

cannot be ignored.

However,

the success of a sovereign

application is still dependent on

its intermediate,

frequent

users until someone else

satisfies both them and

inexperienced

users.

WordStar,

an early word processing program, is a

good example. It dominated

the

word

processing marketplace in the late

70s and early 80s

because it served its

intermediate

users exceedingly well, even

though it was extremely

difficult for

infrequent

and first-time users.

WordStar Corporation thrived

until its competition

offered

the same power for

intermediate users while

simultaneously making it

much

less

painful for infrequent

users. WordStar, unable to

keep up with the

competition,

rapidly

dwindled to insignificance.

TAKE THE

PIXELS

Because

the user's interaction with

a sovereign program dominates

his session at the

computer,

the program shouldn't be

afraid to take as much

screen real estate as

possible.

No other program will be competing

with yours, so expect to

take advantage

of it

all. Don't waste space, but

don't be shy about taking

what you need to do the

job.

If you

need four toolbars to cover

the bases, use four

toolbars. In a program of a

different

posture, four toolbars may

be overly complex, but the

sovereign posture has

a

defensible claim on the

pixels.

In most instances,

sovereign programs run

maximized. In the absence of

explicit

instructions

from the user, your

sovereign application should

default to maximized

(full-screen)

presentation. The program

needs to be fully resizable

and must work

reasonably

well in other screen

configurations, but it must optimize

its interface for

full-screen

instead of the less likely

cases.

Because

the user will stare at a

sovereign application for

long periods, you

should

take

care to mute the colors

and texture of the visual

presentation. Keep the

color

palette

narrow and conservative. Big

colorful controls may look

really cool to

newcomers,

but they seem garish

after a couple of weeks of daily

use. Tiny dots or

accents

of color will have more

effect in the long run

than big splashes, and

they

enable

you to pack controls

together more tightly than

you could otherwise. Your

user

will

stare at the same palettes,

menus, and toolbars for many

hours, gaining an

innate

sense of

where things are from

sheer familiarity. This

gives you, the

designer,

freedom

to do more with fewer

pixels. Toolbars and their

controls can be smaller

than

normal.

Auxiliary controls like

screen-splitters, rulers, and

scroll bars can be

smaller

and

more closely spaced.

RICH VISUAL

FEEDBACK

Sovereign

applications are great

platforms for creating an

environment rich in

visual

feedback

for the user. You

can productively add extra

little bits of information

into

the

interface. The status bar at

the bottom of the screen,

the ends of the

space

236

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

normally

occupied by scroll bars, the

title bar, and other

dusty corners of the

program's

visible extents can be

filled with visual

indications of the program's

status,

the

status of the data, the

state of the system, and

hints for more productive

user

actions.

However, be careful: While

enriching the visual

feedback, you must be

careful

not to create an interface

that is hopelessly

cluttered.

The

first-time user won't even

notice such artifacts, let

alone understand

them,

because

of the subtle way they are

shown on the screen. After a

couple of months of

steady

use, however, he will begin to

see them, wonder about

their meaning, and

experimentally

explore them. At this point,

the user will be willing to

expend a little

effort to

learn more. If you provide

an easy means for him to

find out what

the

artifacts

are, he will become not only a better

user, but a more satisfied

user, as his

power

over the program grows

with his understanding.

Adding such richness to

the

interface

is like adding a variety of

ingredients to a meat stock -- it

enhances the

entire

meal.

RICH

INPUT

Sovereign

programs similarly benefit

from rich input. Every

frequently used aspect

of

the

program should be controllable in

several ways. Direct

manipulation, dialog

boxes,

keyboard mnemonics, and

keyboard accelerators are all

appropriate. You can

make

more aggressive demands on the user's

fine motor skills with

direct-

manipulation

idioms. Sensitive areas on

the screen can be just a

couple of pixels

across

because you can assume

that the user is established

comfortably in his

chair,

arm

positioned in a stable way on his desk,

rolling his mouse firmly

across a resilient

mouse

pad.

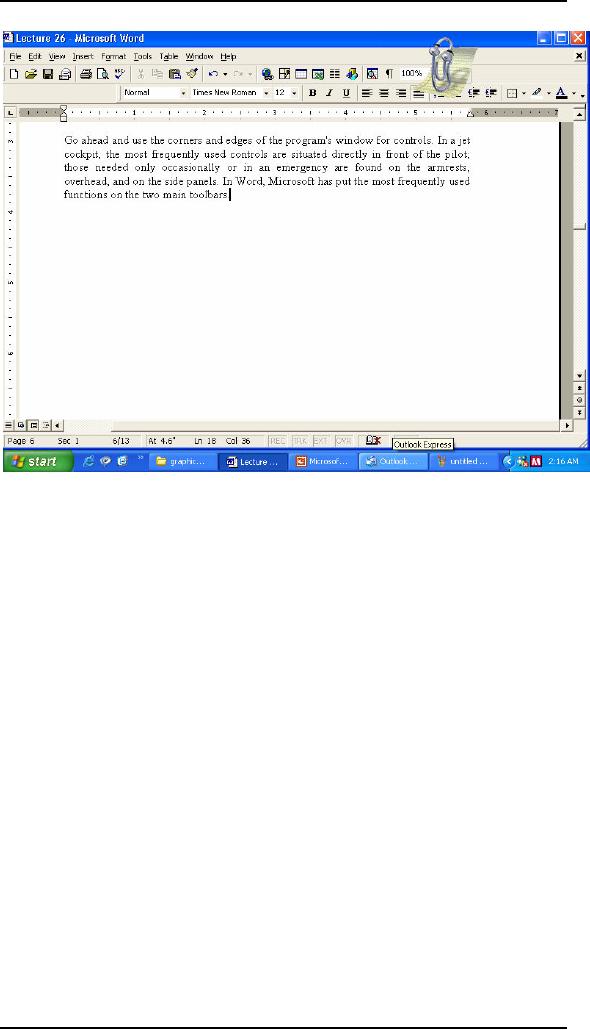

Go ahead

and use the corners and

edges of the program's

window for controls. In a

jet

cockpit,

the most frequently used

controls are situated

directly in front of the

pilot;

those needed

only occasionally or in an emergency

are found on the

armrests,

overhead,

and on the side panels. In

Word, Microsoft has put

the most frequently

used

functions

on the two main

toolbars.

237

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

They

put the frequently used

but visually dislocating

functions on small controls

to

the

left of the horizontal

scroll bar near the

bottom of the screen. These

controls

change

the appearance of the entire

visual display -- Normal

view, Page layout

view

and

Outline view. Neophytes do

not often use them

and, if accidentally triggered,

they

can be

confusing. By placing them near

the bottom of the screen,

they become almost

invisible

to the new user. Their

segregated positioning subtly and

silently indicates

that

caution should be taken in

their use. More experienced

users, with more

con-

fidence

in their understanding and

control of the program, will

begin to notice these

controls

and wonder about their

purpose. They can

experimentally select them

when

they

feel fully prepared for

their consequence. This is a very

accurate and useful

mapping

of control placement to

usage.

The

user won't appreciate

interactions that cause a

delay. Like a grain of sand

in your

shoe, a

one- or two-second delay

gets painful after a few

repetitions. It is perfectly

acceptable

for functions to take time,

but they should not be

frequent or repeated

procedures

during the normal use of

the product. If, for

example, it takes more than

a

fraction

of a second to save the user

s work to disk, the user

quickly comes to view

that

delay as unreasonable. On the

other hand, inverting a

matrix or

changing the entire

formatting

style of a document can take

a few seconds without

causing irritation

because

the user can plainly

see what a big job it

is. Besides, he won't invoke it

very

often.

238

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

DOCUMENT-CENTRIC

APPLICATIONS

The

dictum that sovereign

programs should fill the

screen is also true of

document

windows

within the program itself.

Child windows containing documents

should

always be

maximized inside the program

unless the user explicitly

instructs otherwise.

Many

sovereign programs are also

document-centric (their primary

functions involve

the

creation and viewing of documents

containing rich data),

making it easy to

confuse

the two, but they

are not the same.

Most of the documents we work

with are

8�-by-l1

inches and won't fit on a standard

computer screen. We strain to

show as

much of

them as possible, which

naturally demands a full-screen

stance. If the docu-

ment

under construction were a

32x32 pixel icon, for

example, a document-centric

program

wouldn't need to take the

full screen. The sovereignty

of a program does not

come from

its document-centricity nor

from the size of the

document -- it comes

from

the nature of the program's

use.

If a

program manipulates a document

but only performs some

very simple, single

function,

like scanning in a graphic, it

isn't a sovereign application

and shouldn't

exhibit

sovereign behavior. Such single-function

applications have a posture of

their

own,

the transient

posture.

Transient

posture

A

transient posture program

comes and goes, presenting a

single, high-relief

function

with a

tightly restricted set of

accompanying controls. The

program is called

when

needed,

appears, performs its job,

and then quickly leaves,

letting the user

continue

his

more normal activity,

usually with a sovereign

application.

The

salient characteristic of transient

programs is their temporary

nature. Because

they

don't stay on the screen

for extended periods of

time, the user doesn't get

the

chance to

become very familiar with

them. Consequently, the

program's user

interface

needs to be unsubtle, presenting

its controls clearly and

boldly with no

possibility

of mistakes. The interface must spell

out what it does: This is

not the place

for

artistic-but-ambiguous images or icons -- it

is

the

place for big buttons

with

precise

legends spelled out in a

slightly oversized, easy-to-read

typeface.

Although

a transient program can

certainly operate alone on

your desktop, it

usually

acts in a

supporting role to a sovereign

application. For example,

calling up the

Explorer

to locate and open a file

while editing another with

Word is a typical

transient

scenario. So is setting your speaker

volume. Because the

transient program

borrows

space at the expense of the

sovereign, it must respect the

sovereign by not

taking

more space on screen than is

absolutely necessary. Where

the sovereign can

dig a

hole and pour a concrete

foundation for itself, the

transient program is just on

a

weekend

campout. It cannot deploy

itself on screen either

graphically or temporally. It

is the

taxicab of the software

world.

BRIGHT AND

CLEAR

Whereas a

transient program must consent the

total amount of screen real

estate it

consumes,

the controls on its surface

can be proportionally larger

than those on a

sovereign

application. Where such

heavy-handed visual design on a

sovereign

program

would pall within a few

weeks, the transient program

isn't on screen long

enough

for it to bother the user.

On the contrary, the bolder

graphics help the user

to

orient

himself more quickly when

the program pops up. The

program shouldn't

restrict

itself to a drab palette,

but should instead paint

itself in brighter colors to

help

239

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

differentiate

it from the hosting

sovereign, which will be more

appropriately shaded in

muted

hues. Transient programs

should use their brighter

colors and bold graphics

to

clearly

convey their purpose -- the

user needs big, bright,

reflective road signs to

keep

him from making the

wrong turn at 100 kilometers

per hour.

Transient

programs should have

instructions built into

their surface. The user

may

only

see the program once a month

and will likely forget the

meanings of the choices

presented.

Instead of a button captioned

Setup, it might be better to

make the button

large

enough to caption it Setup

User Preferences. The meaning is

clearer, and the

button

more reassuring. Likewise, nothing

should be abbreviated on a

transient

program

--everything should be spelled

out to avoid confusion. The

user should be

able to

see without difficulty that

the printer is busy, for

example, or that the audio

is

five

seconds long.

KEEP IT

SIMPLE

After

the user summons a transient

program, all the information

and facilities he

needs

should be right there on the

surface of the program's single

window. Keep the

user's

focus of attention on that

window and never force

him into supporting

subwindows

or dialog boxes to take care

of the main function of the

program. If you

find

yourself adding a dialog box

or second view to a transient

application, that's a

key

sign that your design

needs a review.

Transient

programs are not the

place for tiny scroll

bars and fussy

point-click-and-

drag

interfaces. You want to keep

the demands here on the

user's fine motor

skills

down to a

minimum. Simple push-buttons

for simple functions are

better. Anything

directly

manipulable must be big enough to

move to easily: at least twenty

pixels

square.

Keep controls off the

borders of the window. Don't

use the window

bottoms,

status

bars, or sides in transient

programs. Instead, position

the controls up close

and

personal

in the main part of the

window.

You

should definitely provide a

keyboard interface, but it must be a

simple one. It

shouldn't

be more complex than Enter,

Escape, and Tab. You

might add the

arrow

keys,

too, but that's about

it.

Of

course, there are exceptions

to the monothematic nature of

transient programs,

although

they are rare. If a

transient program performs

more than just a

single

function,

the interface should

communicate this visually.

For example, if the

program

imports

and exports graphics, the

interface should be evenly

and visually split

into

two

halves by bold coloration or

other graphics One half

could contain the

controls

for

importing and the other

half the controls for

exporting The two halves

must be

labeled

unambiguously. Whatever you

do, don't add more

windows or dialogs.

Keep in

mind that any given

transient program may be

called upon to assist in

the

management of

some aspect of a sovereign

program. This means that

the transient

program,

as it positions itself on top of

the sovereign, may obscure

the very

information

that it is chartered to work

on. This implies that

the transient program

must be

movable, which means it must

have a title bar.

It is

vital to keep the amount of

management' overhead as low as possible

with

transient

programs. All the user wants

to do is call the program

up, request a function,

and

then end the program. It is

completely unreasonable to force

the user to add

non-

productive

window-management tasks to this

interaction.

240

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

REMEMBERING

STATE

The most

appropriate way to help the

user with both transient

and sovereign apps is

to

give

the program a memory. If the

transient program remembers where it

was the last

time it

was used, the chances are

excellent that the same

size and placement will

be

appropriate

next time, too. It will

almost always be more apt

than any default

setting

might

chance to be. Whatever shape

and position the user

morphed the program

into

is the

shape and position the

program should reappear in

when it is next summoned.

Of course,

this holds true for

its logical settings,

too.

On the

other hand, if the use of

the program is really simple

and single-minded, go

ahead and

specify its shape -- omit

the frame, the directly

resizable window

border.

Save

yourself the work and

remove the complexity from

the program (be

careful,

though,

as this can certainly be abused).

The goal here is not to save

the programmer

work --

that's just a collateral benefit --

but to keep the user

aware of as few

complexities

as possible. If the program's

functions don't demand

resizing and the

overall

size of the program is

small, the principle that

simpler is better takes on

more

importance

than usual. The calculator

accessory' in Windows and on

the Mac, for

example,

isn't resizable. It is always

the correct size and

shape.

No doubt

you have already realized

that almost all dialog

boxes are really

transient

programs.

You can see that

all the preceding guidelines

for transient programs

apply

equally

well to the design of dialog

boxes .

Daemonic

posture

Programs

that do not normally

interact with the user are

daemonic posture

programs.

These

programs serve quietly and

invisibly in the background,

performing possibly

vital

tasks without the need for

human intervention. A printer

driver is an excellent

example.

As you

might expect, any discussion of

the user interface of

daemonic programs is

necessarily

j short. Too frequently,

though, programmers give

daemonic programs

full-screen

control panels that are

better suited to sovereign

programs. Designing

your

fax

manager in the image of Excel,

for example, is a fatal

mistake. At the other end

of

the

spectrum, daemonic programs are, too

frequently, unreachable by the

user,

causing

no end of frustration when adjustments

need to be made.

Where a

transient program controls

the execution of a function,

daemonic programs

usually

manage processes. Your heartbeat

isn't a function that must be

consciously

controlled;

rather, it is a process that

proceeds autonomously in the

background. Like

the

processes that regulate your

heartbeat, daemonic programs

generally remain

completely

invisible, competently performing

their process as long as

your computer

is turned

on. Unlike your heart,

however, daemonic programs must

occasionally be

installed

and removed and, also

occasionally, they must be adjusted to

deal with

changing

circumstances. It is at these times that

the daemon talks to the

user. Without

exception,

the interaction between the

user and a daemonic program

is transient in

nature,

and all the imperatives of

transient program design

hold true here also.

The

principles of transient design

that are concerned with

keeping the user

informed

of the

purpose of the program and of

the scope and meaning of

the user's available

choices become

even more critical with

daemonic programs. In many

cases, the user

will not

even be consciously (or

unconsciously) aware of the

existence of the

daemonic

program. If you recognize

that, it becomes obvious

that reports about

status

241

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

from

that program can be quite

dislocating if not presented in an

appropriate context.

Because

many of these programs

perform esoteric functions -- like

printer drivers or

communications

concentrators -- the messages from

them must take particular

care

not to

confuse the user or lead to

misunderstandings.

A

question that is often taken

for granted with programs of

other postures becomes

very

significant with daemonic

programs: If the program is

normally invisible,

how

should

the user interface be summoned on

those rare occasions when it

is needed?

One of

the most frequently used methods is to

represent the daemon with an

on-screen

program

icon found either in the

status area (system tray) in

Windows or in the far

right of

the Mac OS menu bar.

Putting the icon so boldly

in the user's face when it

is

almost

never needed is a real affront,

like pasting an advertisement on

the windshield

of somebody's car. If

your daemon needs

configuring no more than once a

day, get it

off of

the main screen. Windows XP

now hides daemonic icons

that are not actively

being

used. Daemonic icons should

only be employed permanently if

they provide

continuous,

useful status

information.

Microsoft

makes a bit of a compromise here by

setting aside an area on the

far-right

side of

the taskbar as a status area

wherein icons belonging to

daemonic posture

programs

may reside. This area, also

known as the system tray,

has been abused by

programmers,

who often use it as a quick

launch area for sovereign

applications. As

of

Windows XP, Microsoft set

the standard that only

status icons are to appear in

the

status

area (a quick launch area is

supported next to the Start

button on the

taskbar),

and

unless the user chooses

otherwise, only icons

actively reporting status

changes

will be

displayed. Any others will be hidden.

These decisions are very

appropriate

handling

of transient programs.

An

effective approach for

configuring daemonic programs is

employed by both the

Mac

and Windows: control panels,

which are transient programs

that run as

launchable

applications to configure daemons. These

give the user a consistent

place

to go for

access to such process-centric

applications.

Auxiliary

posture

Programs

that blend the characteristics of

sovereign and transient

programs exhibit

auxiliary

posture. The auxiliary

program is continuously present like a

sovereign, but

it

performs only a supporting

role. It is small and is

usually superimposed on

another

application

the way a transient is.

The Windows taskbar, clock

programs,

performance

monitors on many Unix

platforms, and Stickies on

the Mac are all

good

examples

of auxiliary programs. People

who continuously use instant

messaging

applications

are also using them in an

auxiliary manner. In Windows

XP's version of

Internet

Explorer, Microsoft has

recognized the auxiliary

role that streaming

audio

can

play while the user is

browsing the Web. It has

integrated its audio player

into a

side pane

in the browser.

Auxiliary

programs are typically

silent reporters of ongoing

processes, although

some,

like

Stickies or stock tickers,

are for displaying other

data the user is interested

in. In

some

cases, this reporting may be

a function that they perform

in addition to actually

managing

processes, but this is not

necessarily true. An auxiliary

application may, for

example,

monitor the amount of system

resources either in use or

available. The

program

constantly displays a small

bar chart reflecting the

current resource

availability.

242

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

A

process-reporting auxiliary program must

be simple and often bold in

reporting its

information.

It must be very respectful of the

pre-eminence of sovereign

programs

and

should be quick to move out

of the way when

necessary.

Auxiliary

programs are not the

locus of the user's

attention; that distinction

belongs to

the host

application. For example,

take an automatic call

distribution (ACD)

program.

An ACD is

used to evenly distribute

incoming calls to teams of

customer-service

representatives

trained either to take

orders, provide support, or

both. Each

representative

uses a computer running an

application specific to his or

her job. This

application,

the primary reason for

the system's purchase, is a sovereign

posture

application;

the ACD program is an auxiliary

application on top of it.

For example, a

sales

agent fields calls from

prospective buyers on an incoming

toll-free number. The

representative's

order entry program is the

sovereign, whereas the ACD program

is

the

auxiliary application, riding on

top to feed incoming calls

to the agent. The ACD

program

must be very conservative in its

use of pixels because it

always obscures

some of

the underlying sovereign

application. It can afford to

have small features

because

it is on the screen for long

periods of time. In other

words, the controls on

the

auxiliary

application can be designed to a

sovereign's sensibilities.

243

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS