|

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Lecture

25

Lecture

25. Design

Synthesis

Learning

Goals

The

aim of this lecture is to

introduce you the study of

Human Computer

Interaction,

so that

after studying this you will

be able to:

· Understand

the design principles

· Discuss

the design patterns and

design imperatives

In the

previous lectures, we've

discussed a process through

which we can achieve

superior

interaction design. But what

makes a design superior?

Design that meets

the

goals

and needs of users (without

sacrificing business goals or

ignoring technical

constraints)

is one measure of design

superiority. But what are

the attributes

of

a

design

that enable it to accomplish

this successfully? Are there

general, context-

specific

attributes and features that a

design can possess to make

it a "good" design?

It is

strongly believed that the

answer to these questions lies in

the use of

interaction

design

principles -- guidelines for

design of useful and useable

form and behavior,

and

also in the use of

interaction design patterns -- exemplary,

generalizable

solutions

to specific classes of design

problem. This lecture

defines these ideas in

more

detail. In addition to design-focused

principles and patterns, we must

also

consider

some larger design

imperatives to set the stage

for the design

process.

Interaction

Design Principles

25.1

Interaction

design principles are

generally applicable guidelines

that address issues

of

behavior,

form, and content. They

represent characteristics of product behavior

that

help

users better accomplish

their goals and feel

competent and confident

while doing

so.

Principles are applied

throughout the design

process, helping us to translate

tasks

that

arise out of scenario iterations into

formalized structures and behaviors in

the

interface.

Principles

minimize work

One of

the primary purposes principles

serve is to optimize the

experience of the

user

when he

engages with the system. In

the case of productivity

tools and other

non-

entertainment-oriented

products, this optimization of

experience means the

minimization

of work (Goodwin,

2002a). Kinds of work to be

minimized include:

· Logical

work --

comprehension of text and

organizational structures

· Perceptual

work --

decoding visual layouts and

semantics of shape,

size,

color,

and representation

226

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Mnemonic

work --

recall of passwords, command

vectors, names

and

·

locations

of data objects and controls,

and other relationships

between objects

Physical/motor

work --

number of keystrokes, degree of mouse

movement,

·

use of

gestures (click, drag,

double-click), switching between

input modes,

extent of

required navigation

Most of

the principles discussed,

attempt to minimize work

while providing

greater

levels of

feedback and contextually

useful information up front to

the user.

Principles

operate at different levels of

detail

Design

principles operate at three

levels of organization: the

conceptual level, the

interaction

level, and the interface

level. Our focus is on

interaction-level principles.

Conceptual-level

principles help define what a

product is and

how it fits into

·

the

broad context of use

required by its primary

personas.

Interaction-level

principles help define how a

product should behave, in

·

general,

and in specific

situations.

Interface-level

principles help define the

look and feel of

interfaces

·

Most

interaction design principles

are cross-platform, although

some platforms, such

as the

Web and embedded systems,

have special considerations

based on the extra

constraints

imposed by that

platform.

Principles

versus style guides

Style

guides rather rigidly define

the look and feel of an

interface according to

corporate

branding and usability

guidelines. They typically

focus at the detailed

widget

level: How many tabs

are in a dialog? What should

button high light

states

look

like? What is the pixel

spacing between a control

and its label? These

are all

questions

that must be answered to create a finely

tuned look and feel

for a product,

but

they don't say much

about the bigger issues of

what a product should be or

how it

should

behave.

Experts

recommend that designers pay

attention to style guides

when they are

available

and when fine-tuning

interaction details, but

there are many bigger

and more

interesting

issues in the design of

behavior that rarely find

their way into style

guides.

Some

design principles are stated

below:

Design

Principles (Norman)

We have

studied all of these

principles in greater detail

earlier, these are:

· Visibility

· Affordance

· Constraints

· Mapping

· Consistency

· Feedback

227

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Nielsen's

design principles:

Visibility

of system status

Always

keep users informed about

what is going on, through

appropriate feedback

within

reasonable time. For example, if a

system operation will take

some time, give

an

indication of how long and

how much is complete.

Match

between system and real

world

The

system should speak the

user's language, with words,

phrases and concepts

familiar

to the user, rather than

system-oriented terms. Follow real-world

conventions,

making

information appear in natural and

logical order.

User

freedom and control

Users

often choose system

functions by mistake and need a

clearly marked

'emergency

exit' to leave the unwanted

state without having to go

through an extended

dialog.

Support undo and

redo.

Consistency

and standards

Users

should not have to wonder

whether words, situations or

actions mean the

same

thing in

different contexts. Follow

platform conventions and accepted

standards.

Error

prevention

Make it

difficult to make errors.

Even better than good

error messages is a

careful

design

that prevents a problem from

occurring in the first

place.

Recognition

rather than recall

Make

objects, actions and options

visible. The user should

not have to remember

information

from one part of the

dialog to another. Instructions

for use of the

system

should be

visible or easily retrievable

whenever appropriate.

Flexibility

and efficiency of use

Allow

users to tailor frequent

actions. Accelerators - unseen by

the novice user -

may

often

speed up the interaction for

the expert user to such an

extent that the system

can

cater to

both inexperienced and

experienced users.

Aesthetic

and minimalist design

Dialogs

should not contain

information that is irrelevant or

rarely needed. Every

extra

unit of

information in a dialog competes

with the relevant units of

information and

diminishes

their relative.

Help

users recognize, diagnose, and recover

from errors

Error

messages should be expressed in

plain language (no codes),

precisely indicate

the

problem, and constructively

suggest a solution.

228

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Help

and documentation

Few

systems can be used with no

instruction so it may be necessary to

provide help

and

documentation. Any such information

should be easy to search,

focused on the

user's

task, list concrete step to be

carried out, and not be

too large.

Design

Principles (Simpson,

1985)

Define

the users

·

Anticipate

the environment in which

your program will be

used

·

Give

the operators control

·

Minimize

operators' work

·

Keep

the program simple

·

Be

consistent

·

Give

adequate feedback

·

Do not

overstress working

memory

·

Minimize

dependence on recall memory

·

Help

the operators remain

oriented

·

Code

information properly (or not

at all)

·

Follow

prevailing design

conventions

·

Design

Principles (Shneiderman,

1992)

1. Strive

for consistency in action

sequences, layout, terminology,

command use and

so

on.

2. Enable

frequent users to use

shortcuts, such as

abbreviations, special

key

sequences

and macros, to perform

regular, familiar actions

more quickly.

3. Offer

informative feedback for

every user action, at a

level appropriate to

the

magnitude

of the action.

4. Design

dialogs to yield closure so that

the user knows when

they have completed a

task.

5. Offer

error prevention and simple

error handling so that,

ideally, users are

prevented

from making mistakes and, if

they do, they are offered

clear and

informative

instructions to enable them to

recover,

6. Permit

easy reversal of actions in order

to relieve anxiety and

encourage

exploration,

since the user knows that he

can always return to the

previous state.

7. Support

internal locus of control so that

the user is in control of

the system, which

responds to

his actions.

8. Reduce

short-term memory load by

keeping displays simple,

consolidating multiple

page

displays and providing time

for learning action

sequences.

These

rules provide useful

shorthand for the more

detailed sets of principles

described

earlier.

Like those principles, they

are not applicable to every

eventuality and need to

be

interpreted for each new

situation. However, they are

broadly useful and

their

application

will only help most design

projects.

Design

Principles (Dumas,

1988)

Put

the user in control

·

Address

the user's level of skill

and knowledge

·

Be consistent in

wording, formats, and

procedures

·

229

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Protect

the user from the

inner workings of the

hardware and software that

is

·

behind

the interface

Provide

online documentation to help

the user to understand how

to operate

·

the

application and recover from

errors

Minimize

the burden on user's

memory

·

Follow

principles of good graphics

design in the layout of the

information on

·

the

screen

Interaction

Design Patterns

25.2

Design

patterns serve two important

functions. The first

function is to capture

useful

design

decisions and generalize

them to address similar

classes of problems in

the

future

(Borchers, 2001). In this

sense, patterns represent both the

capture and

formalization

of design knowledge, which

can serve many purposes.

These include

reducing

design time and effort on

new projects, educating designers

new to a project,

or -- if

the pattern is sufficiently

broad in its application --

educating designers new

to the

field.

Although

the application of patterns in

design pedagogy and

efficiency is certainly

important,

the key factor that

makes patterns exciting is

that they can

represent

optimal

or near-optimal interactions for

the user and the

class of activity that

the

pattern

addresses.

Interaction

and architectural

patterns

Interaction

design patterns are far more

akin to the architectural

design patterns first

envisioned

by Christopher Alexander in his

seminal volumes A Pattern

Language

(1977)

and The

Timeless Way of Building (1979)

than they are to the

popular

engineering

use of patterns. Alexander sought to

capture in a set of building

blocks

something

that he called "the

quality without a name,"

that essence of

architectural

design

that creates a feeling of

well-being in the inhabitants of

architectural structures.

It is

this human element that

differentiates interaction design

patterns (and

architectural

design patterns) from

engineering design patterns, whose

sole concern is

efficient

reuse of code.

One

singular and important way

that interaction design

patterns differ from

architectural

design patterns is their concern,

not only with structure

and organization

of elements,

but with dynamic behaviors

and changes in elements in response to

user

activity.

It is tempting to view the

distinction simply as one of change

over time, but

these

changes are interesting

because they occur in

response to human activity.

This

differentiates

them from preordained

temporal transitions that

can be found in

artifacts

of broadcast and film media

(which have their own

distinct set of

design

patterns).

Jan Borchers (2001) aptly

describes interaction design

patterns:

[Interaction

design] Patterns refer to relationships

between physical

elements

and the events that happen

there. Interface designers, like

urban

architects,

strive to create environments

that establish certain

behavioral

230

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

patterns

with a positive effect on those

people 'inside' these

environments .

. . 'timeless'

architecture is comparable to user

interface qualities such

as

'transparent'

and 'natural.'

Types of

interaction design

patterns

Like most

other design patterns,

interaction design patterns

can be hierarchically

organized

from the system level

down to the level of

individual interface

widgets.

Like

principles, they can be

applied at different levels of

organization (Goodwin,

2002a):

Postural

patterns can be applied at

the conceptual level and

help determine the

·

overall

product stance in relation to

the user.

Structural

patterns solve problems that

relate to the management of

·

information

display and access, and to

the way containers of data

and

functions

are visually manipulated to

best suit user goals

and contexts. They

consist of

views, panes, and element

groupings.

Behavioral

patterns solve wide-ranging

problems relating to

specific

·

interactions

with individual functional or data

objects or groups of

such

objects.

What most people think of as

system and widget behaviors

fall into

this

category.

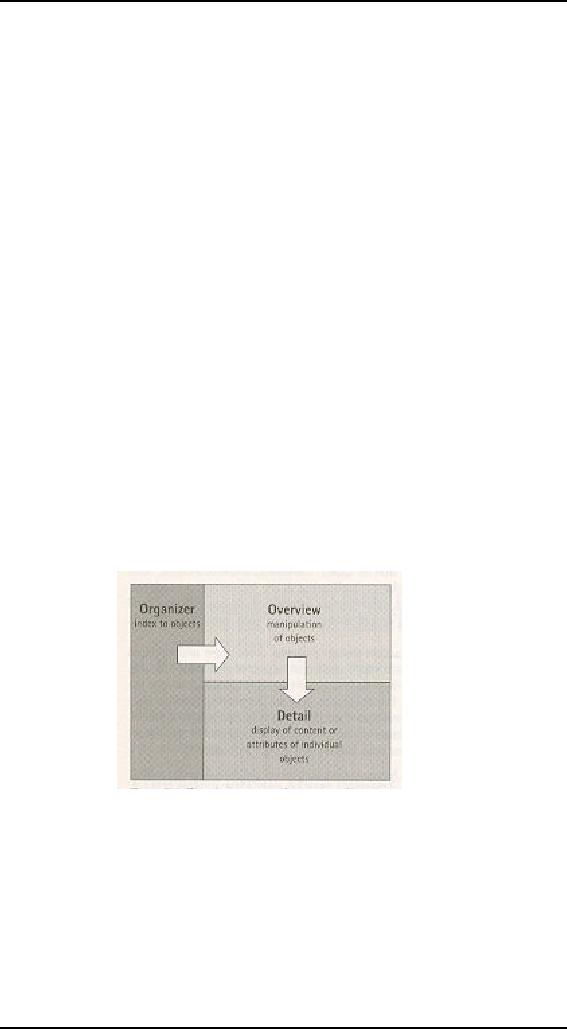

Structural

patterns are perhaps the

least-documented patterns, but

they are nonetheless

in

widespread use. One of the

most commonly used high-level

structural patterns is

apparent

in Microsoft Outlook with

its navigational pane on the

left, overview pane

on the

upper right, and detail pane

on the lower right (see

Figure).

231

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

This

pattern is optimal for

full-screen applications that

require user access to

many

different

kinds of objects, manipulation of

those objects in groups, and

display of

detailed

content or attributes of individual

objects or documents. The pattern

permits

all

this to be done smoothly in a

single screen without the

need for additional

windows.

Many e-mail clients make

use of this pattern, and

variations of it appear in

many

authoring and information management

tools where rapid access to

and

manipulation

of many types of objects is

common

Structural

patterns, pattern nesting,

and pre-fab design

Structural

patterns often contain other

structural patterns; you

might imagine that a

comprehensive

catalogue of structural patterns could,

given a clear idea of user

needs,

permit

designers to assemble coherent,

Goal-Directed designs fairly rapidly.

Although

there is

some truth in this assertion,

which the experts have

observed in practice, it is

simply

never the case that

patterns can be mechanically

assembled in cookie-cutter

fashion.

As Christopher Alexander is swift to

point out (1979),

architectural patterns

are the

antithesis of the pre-fab

building, because context is of

absolute importance in

defining

the actual rendered form of

the pattern in the world.

The environment where

the

pattern is deployed is critical, as are

the other patterns that

comprise it, contain

it,

and

abut it. The same is

true for interaction design

patterns. The core of each

pattern

lies in

the relationships between represented

objects and between those

objects and

the

goals of the user. The

precise form of the pattern is

certain to be somewhat

different

for each instance, and

the objects that define it

will naturally vary

from

domain to

domain. But the

relationships between objects

remain essentially the

same.

Interaction

Design Imperatives

25.3

Beyond

the need for principles of

the type described

previously, the experts also

feel a

need for

some even more fundamental

principles for guiding the

design process as a

whole.

The following set of

top-level design imperatives

(developed by Robert

Reimann,

Hugh Dubberly, Kim Goodwin,

David Fore, and Jonathan

Korman) apply

to

interaction design, but

could almost equally well

apply to any design

discipline.

Interaction

designers should create design

solutions that are

· Ethical

[considerate,

helpful]

Do no

harm

Improve

human situations

Purposeful

[useful,

usable]

·

Help

users achieve their goals

and aspirations

Accommodate

user contexts and

capacities

Pragmatic

[viable,

feasible

·

Help

commissioning organizations achieve

their goals 7

232

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Accommodate

business and technical

requirements

Elegant

[efficient,

artful, affective]

·

Represent

the simplest complete

solution

Possess

internal (self-revealing, understandable)

coherence

Appropriately

accommodate and stimulate cognition

and emotion

Ask

relevant questions when

planning manuals

·

Learn

about your audiences

·

Understand

how people use

manuals

·

Organize

so that users can find

information quickly

·

Put

the user in control by

showing the structure of the

manual

·

Use

typography to give readers clues to

the structure of the

manual

·

Write so

that users can picture

themselves in the text

·

Write so

that you don't overtax

users' working memory

·

Use

users' words

·

Be

consistent

·

Test for

usability

·

Expect to

revise

·

Understand

who uses the product

and why

·

Adapt

the dialo to the

user

·

Make

the information

accessible

·

Apply a

consistent organizational strategy

·

Make

messages helpful

·

Prompt

for inputs

·

Report

status clearly

·

Explain

errors fully

·

Fir

help smoothly into the

users' workflow

·

233

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS