|

USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS |

| << USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH |

| REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN >> |

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

team who

should definitely not be the

design target for the

product. Good candidates

for

negative personas are often

technologiy-savvy early-adopter personas

for

consumer

products and IT specialists for end-user

enterprise products.

Lecture

22

Lecture

22. User

Modeling

Learning

Goals

As the

aim of this lecture is to

introduce you the study of

Human Computer

Interaction,

so that after studying this

you will be able to:

� Understand

how to conduct ethnographic

interviews

� Discuss

briefly other research

techniques

The most

powerful tools are simple in

concept, but must be applied

with some

sophistication.

The most powerful interaction

design tool used is a precise

descriptive

model of

the user, what he wishes t

accomplish, and why. The

sophistication becomes

apparent

in the way we construct and

use that model.

These

user models, which we call

personas, are not real

people, but they are

based on

the

behaviors and motivations of

real people and represent

them throughout the

design

process.

They are composite archetypes based on

behavioral data gathered from

many

actual

users through ethnographic

interviews. We discover out

personas during the

course of

the Research phase and

formalize them in the

Modeling phase, by

understanding

our personas, we achieve and

understanding of our users'

goals in

specific

context--a critical tool for

translating user data into

design framework.

There

are many useful models

that can serve as tools

for the interaction

designer, but

it is

felt that personas are

among the strongest.

Why

Model?

22.1

Models

are used extensively in

design, development, and the

sciences. They are

powerful

tools for representing

complex structures and relationships

for the purpose

of better

understanding or visualizing them.

Without models, we are left to

make

sense of

unstructured, raw data,

without the benefit of the

pig picture or any

organizing

principle. Good models emphasize

the salient features of the structures

or

relationships

they represent and de-emphasize the

less significant

details.

Because

we are designing for users, it is

important that we can

understand and

visualize

the salient aspects of their

relationships with each

other, with their social

and

physical

environment and of course, with

the products we hope to

design.

197

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Just as

physicists create models of

the atom based on raw,

observed data and

intuitive

synthesis of

the patterns in their data, so must

designers create models of users

based

on raw,

observed behaviors and

intuitive synthesis often patterns in the

data. Only

after we

formalize such patterns can we

hope to systematically construct patterns

of

interactions

that smoothly match the

behaviors, mental models and

goals of users.

Personas

provide this

formalization.

Personas

22.2

To create a

product that must satisfy a

broad audience of users,

logic tells you to

make

it as

broad in its functionality as

possible to accommodate the most people.

This logic,

however,

is flawed. The best way to

successfully accommodate a variety of

users is to

design

for specific types of

individuals with specific

needs.

When

you broadly and arbitrarily

extend a product's functionality to

include many

constituencies,

you increase the cognitive

load and navigational

overhead for all

users.

Facilities that map please

some users will likely

interfere with the

satisfaction

of

other.

A simple

example of how personas are

useful is shown in figure

below, if you try to

design an

automobile that pleases

every possible driver, you

end up with a car

with

every

possible feature, but which

pleases nobody. Software

today is too often

designed

to please to many users,

resulting in low user

satisfaction

But by

designing different cars for

different people with

different specific goals,

as

shown in

figure below, we are able to

create designs that other

people with similar

needs to

our target drivers also

find satisfying. The same

hold true for the

design of

digital

products and

software.

198

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

The

key is in choosing the right

individuals to design for,

ones whose needs represent

the

needs of a larger set of key

constituents, and knowing

how to prioritize

design

elements to

address the needs of the

most important users without

significantly

inconveniencing

secondary users. Personas provide a

powerful tool for

understanding

user

needs, differentiating between

different types of users,

and prioritizing

which

users

are the most important to

target in the design of

function and

behavior.

Personas

were introduced as a tool

for user modeling, they

have gained great

popularity

in the usability community,

but they have also been the

subjects of some

misunderstandings.

Strengths

of personas as a design

tool

The

persona is a powerful, multipurpose

design tool that helps

overcome several

problems

that currently plague the

development of digital products.

Personas help

designers"

Determine

what a product should do and

how it should behave.

Persona goals

�

and

tasks provide the basis

for the design

effort.

Communicate

with stakeholders, developers,

and other designers.

Personas

�

provide a

common language for

discussing design decisions,

and also help

keep

the design centered on users at

every step in the

process.

Build

consensus and commitment to

the design. With a common

language

�

comes a

common understanding. Personas reduce

the need for

elaborate

diagrammatic

models because, as it is found, it is

easier to understand the

many

nuances of user behavior

through the narrative structures

that personas

employ.

Measure

the design's effectiveness.

Design choices can be tested on a

persona

�

in the

same way that they

can be show to a real user

during the formative

process.

Although this doesn't

replace the need to test on

real users. It

provides

a powerful reality check

tool for designers trying to

solve design

problems.

This allows design iteration

to occur rapidly and

inexpensively at

199

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

the

whiteboard, and it results in a far

stronger design baseline

when the time

comes to

test with real

users.

Contribute

to other product-related efforts

such as marketing and sales

plan. It

�

has been

seen that clients repurpose

personas across their

organization,

informing

marketing campaigns, organizational

structure, and other

strategic

planning

activities. Business units outside of

product development

desire

sophisticated

knowledge of a product's users

and typically view personas

with

great

interest.

Personas

and user-centered

design

Personas

also resolve three User-Centered

design issues that arise

during product

development:

� The

elastic user

� Self-referential

design

� Design

edge cases

The

elastic user

Although

satisfying the user is goal,

the term user causes

trouble when applied

to

specific

design problems and

contexts. Its imprecision

makes it unusable as a

design

tool--every

person on a product team has his

own conceptions of the user

and what

the

user needs. When it comes

time to make a product

decisions, this "user"

becomes

elastic,

bending and stretching to

fit the opinions and

presuppositions of whoever

has

the

floor.

If

programmers find it convenient to

simply drop a user into a

confuting file system

of

nested

hierarchical folders to find

the information she needs,

they define the

elastic

user as

an accommodating, computer-literate power

user. Other times, when

they find

it more

convenient to step the user

through a difficult process

with a wizard, they

define

the elastic user as an

unsophisticated first-time user.

Designing for the

elastic

user

gives the developer license

to code as he pleases while still

apparently serving

"the

user". However, our goal is

to design software that

properly meets real

user

needs.

Real users--and the personas

representing them--are not

elastic, but rather

have

specific requirements based on

their goals, capabilities,

and contexts.

Self-referential

design

Self-referential

design occurs when designers or

developers project their own

goals,

motivations,

skills, and mental models

onto a product's design.

Most "cool" product

designs

fall into this category:

the audience doesn't extend

beyond people like

the

designer,

which is fine for a narrow

range of products and completely

inappropriate

for most

others. Similarly, programmers

apply self-referential design

when they create

implementation-model

products. They understand

perfectly how it works and

are

comfortable

with such products. Few

non-programmers would

concur.

Design

edge cases

Another

syndrome that personas help

prevent is designing for edge

cases--those

situations

that might possibly happen,

but usually won't for

the target personas.

200

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Naturally,

edge cases must be programmed for,

but they should never be

the design

focus.

Personas provide a reality

check for the

design.

Personas

are based on research

Personas

must, like any model, be

based on real-world observation.

The primary

source of

data used to synthesize personas must be

from ethnographic

interviews,

contextual

inquiry, or other similar

dialogues with and

observation of actual

and

potential

users. Other data that can

support and supplement the

creation of personas

include,

in rough order of

efficacy:

� Interviews

with users outside of their

use contexts

� Information

about users supplied by

stakeholders and subject

matter experts

� Market

research data such as focus

groups and surveys

� Market

segmentation models

� Data

gathered from literature

reviews and previous

studies

However,

none of this supplemental data

can take the place of

direct interaction

with

and

observation of users in their

native environments. Almost

every word in a well-

developed

persona's description can be traced

back to user quotes or

observed

behaviors.

Personas

are represented as

individuals

Personas

are user models that

are represented as specific, individual

humans. They are

not

actual people, but are

synthesized directly from

observations of real people.

One

of the

key elements that allow

personas to be successful as user

models is that they

are

personifications.

They are represented as specific

individuals. This is appropriate

and

effective

because of the unique

aspects of personas as user

models: they engage

the

empathy

of the development team toward

the human target of design.

Empathy is

critical

for the designers, who will be

making their decisions for

design frameworks

and

details based on both the

cognitive and emotional

dimensions of the persona, as

typified

by the persona's goals.

However, the power of

empathy should not be

quickly

discounted

for other team members.

Personas

represent classes of users in

context

Although

personas are represented as specific

individuals, at the same

time they

represent a

class or type of user of a

particular interactive product.

Specifically,

persona

encapsulates a distinct set of

usage patterns, behavior patterns

regarding the

use of a

particular product. These

patterns are identified

through an analysis of

ethnographic

interviews, supported by supplemental

data if necessary or appropriate.

These

patterns, along with work or

lifestyle-related roles define

personas as user

archetype.

Personas are also referred as

composite user archetypes because

personas

are in

sense composites assembled by clustering

related usage patterns

observed

across

individuals in similar roles

during the research

phase.

Personas

and reuse

Organizations

with more than one

product often want to reuse

the same personas.

However,

to be effective, personas must be

context-specific--they should be

focused

201

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

on the

behaviors and goals related

to the specific domain of a

particular product.

Personas,

because they are constructed

from specific observations of

users interacting

with

specific products in specific

contexts, cannot easily be

reused across

products

even

when those products form a

closely linked suite. Even

then, the focus of

behaviors

may be quite different in

one product than in another,

so researchers must

take

care to perform supplemental

user research.

Archetypes

versus stereotype

Don't

confuse persona archetype with

stereotypes. Stereotypes are, in most

respects,

the

antithesis of well-developed personas.

Stereotypes represent designer or

researcher

biases and assumptions, rather

than factual data. Personas

developed

drawing

on inadequate research run

the risk of degrading to

stereotypical caricatures.

Personas

must be developed and treated

with dignity and respect

for the people

whom

they

represent. Personas also bring to

the forefront issues of

social and political

consciousness.

Because personas provide a precise

design target and also

serve as a

communication

tool to the development team,

the designer much choose

particular

demographic

characteristics with care.

Personas

should be typical and

believable, but not

stereotypical.

Personas

explore ranges of

behavior

The

target market for a product

describes demographics as well as

lifestyle and

sometimes

job roles. What it does

not describe are the ranges of

different behaviors

that

members of that target

market exhibit regarding the

product itself and

product-

related

contexts. Ranges are

distinct from averages: personas do

not seek to establish

an average

user, but rather to identify

exemplary types of behaviors

along identified

ranges.

Personas

fill the need to understand how

users behave within given

product domain--

how

they think about it and

what they do with it--as

well as how they behave in

other

contexts

that may affect the

scope and definition of the

product. Because

personas

must describe

ranges f behavior to capture

the various possible ways

people behave

with

the product, designers must identify a

collection or cast of personas

associated

with

any given product.

Personas

must have motivations

All humans

have motivations that drive

their behaviors; some are

obvious, and many

are

subtle. It is critical that

personas capture these

motivations in the form of

goals.

The

goals we enumerate for our

personas are shorthand

notation for motivations

that

not

only point at specific usage

patterns, but also provide a

reason why those

behaviors

exist. Understanding why a

user performs certain tasks

gives designers

great

power to improve or even

eliminate those tasks, yet

still accomplish the

same

goals.

Personas

versus user roles

User

roles and user profiles

each share similarities with

personas; that is, they

both

seek to

describe relationships of users to

products. But persona and

the methods by

which

they are employed as a design

tool differ significantly

from roles and

profiles

in

several key aspects.

User

roles or role models, are an

abstraction, a defined relationship

between a class of

users

and their problems,

including needs, interests, expectations,

and patterns of

202

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

behavior.

Holtzblatt and Beyer's use

of roles in consolidated flow,

cultural, physical,

and

sequence models is similar in

that it attempts to isolate various

relationships

abstracted

from the people possessing

these relationships.

Problem

with user role

There

are some problems with

user roles:

It is

more difficult to properly

identify relationships in the abstract,

isolated

�

from

people who posses them--the

human power of empathy

cannot easily be

brought

to bear on abstract classes of

people.

Both

methods focus on tasks almost

exclusively and neglect the

use of goals

�

as an

organizing principle for

design thinking and

synthesis.

Holzblatt

and Beyer's consolidated

models, although useful and

encyclopedic

�

in scope,

are difficult to bring

together as a coherent tool

for developing,

communicating,

and measuring design

decisions.

Personas

address each of these

problems. Well-developed personas

incorporate the

same

type of relationships as user

roles do, but express

them in terms of goals

and

examples

in narrative.

Personas

versus user profile

Many

usability parishioners use

the terms persona and user

profile synonymously.

There is

no problem with this if the

profile is truly generated

from ethnographic data

and

encapsulates the depth of

information. Unfortunately, all

too often, it has

been

seen

that user profile =s that

reflect Webster's definition of

profile as a `brief

biographical

sketch." In other words,

user profiles are often a

name attached to

brief,

usually

demographic data, along with

a short, fictional paragraph

describing the kind

of car

this person drives, how many

kids he has, where he lives,

and what he does

for

a living.

This kind of user profile is

likely to be a user stereotype

and is not useful as

a

design

tool. Personas, although has

names and sometimes even

cars and family

members,

these are employed sparingly

as narrative tools to help

better communicate

the

real data and are not ends

in themselves.

Personas

versus market

segments

Marketing

professionals may be familiar

with a process similar to

persona

development

because it shares some

process similarities with

market definition.

The

main

difference between market

segments and design personas

are that the former

are

based on

demographics and distributed channels,

where as the latter are

based on user

behaviors

and goals. The two are

not the same and

don't serve the same purpose.

The

marketing

personas shed light on the

sales process, whereas the

design personas shed

light on

the development process.

This said, market segments

play role in personas

development.

User

personas versus non-user

personas

A

frequent product definition

error is to target people

who review, purchase, or

administer

the product, but who

are not end users.

Many products are designed

for

columnists

who review the product in

consumer publications. IT managers

who

203

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

purchase

enterprise products are, typically,

not the users the

products. Designing

for

the

purchaser is a frequent mistake in the

development of digital

products.

In

certain cases, such as for

enterprise systems that

require maintenance

and

administrator

interface; it is appropriate to create

non-user personas. This

requires that

research

be expanded to include these

types of people.

Goals

22.3

If

personas provide the context

for sets of observed

behaviors, goals are the

drivers

behind

those behaviors. A persona without

goals can still serve as a

useful

communication

tool, but it remains useless

as a design tools. User

goals serve as a

lens

through which designers must consider

the functions of a product.

The function

and

behavior of the product must

address goals via

tasks--typically as few tasks

as

absolutely

necessary.

Goals

motivate usage

patterns

People's

or personas' goals motivate

them to behave the way

they do. Thus,

goals

provide

not only answer to why and

how personas desire to use a

product, but can

also

serve as a shorthand in the

designer's mind for the

sometimes complex behaviors

in which

a persona engages and, therefore,

for the tasks as

well.

Goals

must be inferred from qualitative

data

You

can't ask a person what his

goals are directly: Either

he won't be able to

articulate

them, or he won't be accurate or even

perfectly honest. People

simply aren't

well

prepared to answer such questions

accurately. Therefore, designers

and

researchers

need to carefully reconstruct goals

from observed behaviors,

answers to

other

questions, non-verbal cues,

and clues from the

environment such as book

titles

on shelves.

One of the most critical

tasks in the modeling of

personas is identifying

goals

and expressing them

succinctly: each goal should

be expressed as a simple

sentence.

Types of

goals

22.4

Goals

come in many different

verities. The most important

goals from a user-centered

design

standpoint are the goals of

users. These are, generally,

first priority in a

design,

especially

in the design of consumer products.

Non-user goals can also come

into

play,

especially in enterprise environments.

The goals of organizations,

employers,

customers,

and partners all need to be acknowledged,

if not addressed directly, by

the

product's

design.

User

goals

User

personas have user goals.

These range from broad aspirations to

highly

pragmatic

product expectations. User

goals fall into three basic

categories

� Life

goals

� Experience

goals

� End

goals

204

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Life

goals

Life

goals represent personal aspirations of

the user that typically go

beyond the

context

of the product being

designed. These goals represent deep

drives and

motivations

that help explain why

the user is trying to

accomplish the end goals

he

seeks to

accomplish. These can be

useful in understanding the

broader context or

relationships

the user may have

with others and her

expectations of the product

from a

brand

perspective.

Examples:

� Be

the best at what I do

� Get

onto the fast track

and win that big

promotion

� Learn

all there is to know about

this field

� Be a

paragon of ethics, modesty

and trust

Life

goals rarely figure directly

into the design of specific

elements of an interface.

However,

they are very much

worth keeping in

mind.

Experience

goals

Experience

goals are simple, universal,

and personal. Paradoxically,

this makes them

difficult

for many people to talk

about, especially in the

context of impersonal

business.

Experience goals express how

someone wants to feel while

using a product

or the

quality of their interaction

with the product.

Examples

� Don't

make mistakes

� Feel

competent and

confident

� Have

funExperience goals represent the

unconscious goals that people

bring to

any

software product. They bring

these goals to the context

without consciously

realizing

it and without necessarily

even being able to

articulate the goals.

End

goals

End

goals represent the user's

expectations of the tangible outcomes of

using specific

product.

When you pick op a cell

phone, you likely have an

outcome in mind.

Similarly,

when you search the

web for a particular item or

piece of information,

you

have

some clear end goals to

accomplish. End goals must be

met for users to

think

that a

product is worth their time

and money, most of the goals

a product needs to

concern

itself with are, therefore,

end goals such as the

following:

� Find

the best price

� Finalize

the press release

� Process

the customer's order

� Create a

numerical model of the

business

Non-user

goals

Customer

goals, corporate goals, and

technical goals are all

non-user goals.

Typically,

these

goals must be acknowledged and

considered, but they do not

form the basis

for

the

design direction. Although

these goals need to be addressed,

they must not be

addressed

at the expense of the user.

205

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Types of

non-user goals

� Customer

goals

� Corporate

goals

� Technical

goals

Customer

goals

Customers, as

already discussed, have

different goals than users.

The exact nature of

these

goals varies quite a bit

between consumer and enterprise

products. Consumer

customers

are often parents, relatives, or

friends who often have

concerns about the

safety

and happiness of the persons

for whom they are

purchasing the

product.

Enterprise

customers are typically IT managers,

and they often have concerns

about

security,

ease of maintenance, and

ease of customization.

Corporate

goals

Business

and other organizations have

their own requirements for

software, and they

are as

high level as the personal

goals of the individual. "To increase

our profit" is

pretty

fundamental to the broad of

directors or the stockholders.

The designers use

these

goals to stay focused on the

bigger issues and to avoid

getting distracted by

tasks or

other false goals.

Examples

� Increase

profit

� Increase

market share

� Defeat

the competition

� Use

resources more

efficiently

� Offer

more products or services

Technical

goals

Most of

the software-based products we

use everyday are created with

technical goals

in mind.

Many of these goals ease

the task of software

creation, which is a

programmer's

goal. This is why they

take precedence at the expense of the

users'

goals.

Example:

� Save

money

� Run

in a browser

� Safeguard

data integrity

� Increase

program execution

efficiency

Constructing

personas

22.5

Creating

believable and useful

personas requires an equal

measure of detailed

analysis

and

creative synthesis. A standardized

process aids both of these

activities

significantly.

Process

of constructing personas involve

following steps:

8.

Revisit the persona

hypothesis

9. Map

interview subjects to behavioral

variables

10.

Identify significant behavior

patterns

11.

Synthesize characteristics and relevant

goals.

206

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

12.

Check for completeness.

13.

Develop narratives

14.

Designate persona types

Revisit

the persona

hypothesis

After

you have completed your

research and performed a

cursory organization of

the

data,

you next compare patterns

identified in the data to

the assumptions make in

the

persona

hypothesis. Were the

possible roles that you

identified truly distinct?

Were

the

behavioral variables you

identified valid? Were there

additional, unanticipated

ones, or

ones you anticipated that

weren't supported by

data?

If your

data is at variance with

your assumptions, you need to add,

subtract, or modify

the

roles and behaviors you

anticipated. If the variance is

significant enough, you

may

consider

additional interviews to cover

any gaps in the new

behavioral ranges

that

you've

discovered.

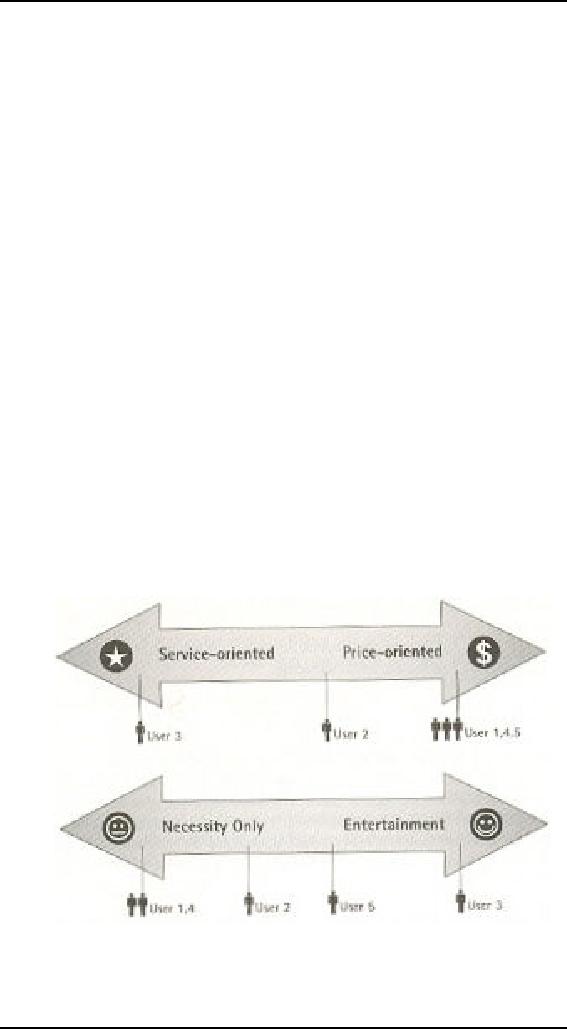

Map

interview subjects to behavioral

variables

After

you are satisfied that

you have identified the

entire set f behavioral

variables

exhibited

by your interview subjects, the

next step is to map each

interviewee against

each

variable range that applies.

The precision of this

mapping isn't as critical

as

identifying

the placement f interviewees in

relationship to each other. It is

the way

multiple

subjects cluster on each variable

axis that is significant as

show in figure.

207

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

Identify

significant behavior

patterns

After

you have mapped your

interview subjects, you see clusters of

particular subjects

that

occur across multiple ranges

or variables. A set of subjects who

cluster in six to

eight

different variables will likely represent

a significant behavior patterns that

will

form

the basis of a persona. Some

specialized role may exhibit

only one significant

pattern,

but typically you will find

two or even three such

patterns. For a pattern to

be

valid,

there must be a logical or causative

connection between the

clustered behaviors,

not

just a spurious

correlation.

Synthesize

characteristic and relevant

goals

For

each significant behavior

pattern you identify, you

must synthesize details from

your

data. Describe the potential

use environment, typical

workday, current

solutions

and

frustrations, and relevant

relationships with

other.

Brief

bullet points describing characteristics

of the behavior are sufficient.

Stick to

observed

behaviors as mush as possible; a

description or two that sharpen

the

personalities

of your personas and help

bring them to life.

One

fictional detail at this

stage is important: the

persona's first name and

last names.

The

name should be evocative of

the type of person the persona

is, without tending

toward

caricature or stereotype.

Goals

are the most critical detail

to synthesize from your interviews

and observations

of

behaviors. Goals are best

derived from an analysis of

the group of

behaviors

comprising

each persona. By identifying the

logical connections between

each

persona's

behaviors, you can begin to

infer the goals that

lead to those behaviors.

You

can

infer goals both by

observing actions and by

analyzing subject responses to

goal-

oriented

interview questions.

Develop

narratives

Your

list of bullet point characteristics

and goals point to the

essence of complex

behaviors,

but leaves much implied.

Third-person narrative is far

more powerful in

conveying

the persona's attitudes,

needs, and problems to other

team members. It also

deepens

the designer's connection to

the personas and their

motivations.

A typical

narrative should not be

longer than one or two

pages of prose. The

narrative

must be

nature, contain some

fictional events and reactions,

but as previously

discussed,

it is not a short story. The

best narrative quickly

introduces the persona in

208

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

terms of

his job or lifestyle, and

briefly sketches a day in

his life, including

peeves,

concerns,

and interests that have

direct bearing on the

product.

Be

careful about precision of

detail in your descriptions.

The detail should not

exceed

the

depth of your

research.

When

you start developing your

narrative, choose photographs f

your personas.

Photographs

make them feel more

real as you create the

narrative and engage

others

on the

team when you are

finished.

Designate

persona types

By now

your personas should feel

very much like a set of

real people that you

feel

you

know. The final step in

persona construction finishes the

process f turning

your

qualitative

research into a powerful set

of design tools.

There

are six types of persona,

and they are typically

designated in roughly

the

ordered

listed here:

� Primary

� Secondary

� Supplemental

� Customer

� Served

� Negative

Primary

personas

Primary

personas represent the primary

target for the design of an

interface. There can

be only

one primary persona per

interface for a product, but

it is possible for

some

products

to have multiple distinct

interfaces, each targeted at a

distinct primary

persona.

Secondary

personas

Sometimes a

situation arises in which a persona

would be entirely satisfied by

a

primary

persona's interface if one or

two specific additional

needs were addressed

by

the

interface. This indicates

that the persona in question is a

secondary persona for

that

interface, and the design of

that interface must address those

needs without

getting

in the way of the primary

persona. Typically, an interface will

have zero to

two

secondary personas.

Supplemental

personas

User

personas that are not

primary or secondary are supplemental

personas: they are

completely

satisfied by one of the

primary interface. There can

be any number of

supplemental

personas associated with an

interface. Often political

personas--the one

added to

the cast to address

stakeholder assumptions--become

supplemental

personas.

Customer

persona

Customer

personas address the needs

of customers, not end users.

Typically, customer

personas

are treated like secondary

personas. However, in some

enterprise

209

Human

Computer Interaction

(CS408)

VU

environment,

some customer personas may be

primary personas for their

own

administrative

interface.

Served

personas

Served

personas are somewhat

different from the persona

types already

discussed.

They

are not users of the

product at all; however,

they are directly affected

by the use

of the

product. Served personas

provide a way to track

second-order social

and

physical

ramifications of products. These

are treated like secondary

personas.

Negative

personas

Like

served personas, negative personas

aren't users of the product.

Unlike served

personas,

their use is purely

rhetorical, to help communicate to

other members of the

team who

should definitely not be the

design target for the

product. Good candidates

for

negative personas are often

technology-savvy early-adopter personas

for consumer

products

and IT specialists for end-user

enterprise products.

210

Table of Contents:

- RIDDLES FOR THE INFORMATION AGE, ROLE OF HCI

- DEFINITION OF HCI, REASONS OF NON-BRIGHT ASPECTS, SOFTWARE APARTHEID

- AN INDUSTRY IN DENIAL, SUCCESS CRITERIA IN THE NEW ECONOMY

- GOALS & EVOLUTION OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- DISCIPLINE OF HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION

- COGNITIVE FRAMEWORKS: MODES OF COGNITION, HUMAN PROCESSOR MODEL, GOMS

- HUMAN INPUT-OUTPUT CHANNELS, VISUAL PERCEPTION

- COLOR THEORY, STEREOPSIS, READING, HEARING, TOUCH, MOVEMENT

- COGNITIVE PROCESS: ATTENTION, MEMORY, REVISED MEMORY MODEL

- COGNITIVE PROCESSES: LEARNING, READING, SPEAKING, LISTENING, PROBLEM SOLVING, PLANNING, REASONING, DECISION-MAKING

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ACTIONS: MENTAL MODEL, ERRORS

- DESIGN PRINCIPLES:

- THE COMPUTER: INPUT DEVICES, TEXT ENTRY DEVICES, POSITIONING, POINTING AND DRAWING

- INTERACTION: THE TERMS OF INTERACTION, DONALD NORMAN’S MODEL

- INTERACTION PARADIGMS: THE WIMP INTERFACES, INTERACTION PARADIGMS

- HCI PROCESS AND MODELS

- HCI PROCESS AND METHODOLOGIES: LIFECYCLE MODELS IN HCI

- GOAL-DIRECTED DESIGN METHODOLOGIES: A PROCESS OVERVIEW, TYPES OF USERS

- USER RESEARCH: TYPES OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHIC INTERVIEWS

- USER-CENTERED APPROACH, ETHNOGRAPHY FRAMEWORK

- USER RESEARCH IN DEPTH

- USER MODELING: PERSONAS, GOALS, CONSTRUCTING PERSONAS

- REQUIREMENTS: NARRATIVE AS A DESIGN TOOL, ENVISIONING SOLUTIONS WITH PERSONA-BASED DESIGN

- FRAMEWORK AND REFINEMENTS: DEFINING THE INTERACTION FRAMEWORK, PROTOTYPING

- DESIGN SYNTHESIS: INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES, PATTERNS, IMPERATIVES

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: SOFTWARE POSTURE, POSTURES FOR THE DESKTOP

- POSTURES FOR THE WEB, WEB PORTALS, POSTURES FOR OTHER PLATFORMS, FLOW AND TRANSPARENCY, ORCHESTRATION

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: ELIMINATING EXCISE, NAVIGATION AND INFLECTION

- EVALUATION PARADIGMS AND TECHNIQUES

- DECIDE: A FRAMEWORK TO GUIDE EVALUATION

- EVALUATION

- EVALUATION: SCENE FROM A MALL, WEB NAVIGATION

- EVALUATION: TRY THE TRUNK TEST

- EVALUATION – PART VI

- THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EVALUATION AND USABILITY

- BEHAVIOR & FORM: UNDERSTANDING UNDO, TYPES AND VARIANTS, INCREMENTAL AND PROCEDURAL ACTIONS

- UNIFIED DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT, CREATING A MILESTONE COPY OF THE DOCUMENT

- DESIGNING LOOK AND FEEL, PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INTERFACE DESIGN

- PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL INFORMATION DESIGN, USE OF TEXT AND COLOR IN VISUAL INTERFACES

- OBSERVING USER: WHAT AND WHEN HOW TO OBSERVE, DATA COLLECTION

- ASKING USERS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES, WALKTHROUGHS

- COMMUNICATING USERS: ELIMINATING ERRORS, POSITIVE FEEDBACK, NOTIFYING AND CONFIRMING

- INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AUDIBLE FEEDBACK, OTHER COMMUNICATION WITH USERS, IMPROVING DATA RETRIEVAL

- EMERGING PARADIGMS, ACCESSIBILITY

- WEARABLE COMPUTING, TANGIBLE BITS, ATTENTIVE ENVIRONMENTS