|

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE |

| << GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION |

| ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE >> |

CHAPTER

VIII.

ROMAN

ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Anderson and

Spiers, Baumeister, Reber.

Choisy,

L'Art

de b�tir chez les

Romains.

Desgodetz, Rome

in her Ancient Grandeur.

Durm, Die

Baukunst

der Etrusker;

Die

Baukunst der Romer.

Lanciani, Ancient

Rome in the Light

of

Modern Discovery;

New

Tales of Old Rome;

Ruins

and Excavations of Ancient

Rome.

De

Martha, Arch�ologie

�trusque et romaine.

Middleton, Ancient

Rome in 1888.

LAND

AND PEOPLE. The

geographical position of Italy conferred

upon her special

and

obvious advantages for taking up and

carrying northward and westward the

arts

of

civilization. A scarcity of good

harbors was the only drawback

amid the blessings

of

a glorious climate, fertile

soil, varied scenery, and rich

material resources. From

a

remote

antiquity Dorian colonists had occupied

the southern portion and the

island

of

Sicily, enriching them with splendid

monuments of Doric art; and

Phoenician

commerce

had brought thither the products of

Oriental art and industry. The

foundation

of Rome in 753 B.C. established the

nucleus about which the sundry

populations

of Italy were to crystallize into the

Roman nation, under the

dominating

influence

of the Latin element. Later on, the

absorption of the conquered

Etruscans

added

to this composite people a race of

builders and engineers, as yet rude

and

uncouth

in their art, but destined to become a

powerful factor in developing the

new

architecture

that was to spring from the contact of

the practical Romans with the

noble

art of the Greek centres.

GENERAL

CHARACTERISTICS. While

the Greeks bequeathed to posterity the

most

perfect

models of form in literary and plastic

art, it was reserved for the Romans

to

work

out the applications of these to

every-day material life. The

Romans were above

all

things a practical people.

Their consummate skill as

organizers is manifest in the

marvellous

administrative institutions of their

government, under which they

united

the

most distant and diverse

nationalities. Seemingly deficient in

culture, they were

yet

able to recast the forms of

Greek architecture in new moulds, and to

evolve

therefrom

a mighty architecture adapted to wholly

novel conditions. They

brought

engineering

into the service of architecture, which they

fitted to the varied

requirements

of government, public amusement,

private luxury, and the common

comfort.

They covered the antique world with

arches and amphitheatres, with

villas,

baths,

basilicas, and temples, all bearing the

unmistakable impress of Rome,

though

wrought

by artists and artisans of divers

races. Only an extraordinary genius

for

organization

could have accomplished such

results.

The

architects of Rome marvellously

extended the range of their art, and gave

it a

flexibility

by which it accommodated itself to the

widest variety of materials

and

conditions.

They made the arch and vault the basis of

their system of design,

employing

them on a scale previously undreamed of,

and in combinations of

surpassing

richness and majesty. They systematized

their methods of construction

so

that

soldiers and barbarians could

execute the rough mass of their

buildings, and

formulated

the designing of the decorative details

so that artisans of moderate

skill

could

execute them with good effect. They

carried the principle of repetition

of

motives

to its utmost limit, and sought to

counteract any resulting monotony by

the

scale

and splendor of the design. Above all

they developed planning into a fine

art,

displaying

their genius in a wonderful variety of

combinations and in an unfailing

sense

of the demands of constructive propriety,

practical convenience, and

artistic

effect.

Where Egyptian or Greek

architecture shows one type of plan, the

Roman

shows

a score.

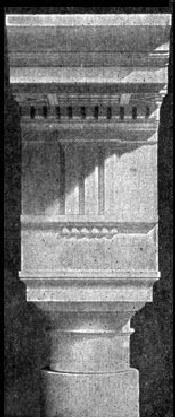

FIG.

42.--ROMAN DORIC ORDER. (THEATRE OF

MARCELLUS).

GREEK

INFLUENCE. Previous

to the closing years of the Republic the

Romans had

no

art but the Etruscan. The few buildings of

importance they possessed were

of

Etruscan

design and workmanship, excepting a

small number built by Greek

hands.

It

was not until the Empire that Roman

architecture took on a truly national

form.

True

Roman architecture is essentially

imperial. The change from the

primitive

Etruscan

style to the splendors of the imperial

age was due to the conquest of

the

Greek

states. Not only did the Greek campaigns

enrich Rome with an

unprecedented

wealth

of artistic spoils; they also

brought into Italy hosts of Greek

artists, and filled

the

minds of the campaigners with the

ambition to realize in their own

dominions the

marble

colonnades, the temples, theatres, and

propyl�a of the Greek cities they

had

pillaged.

The Greek orders were

adopted, altered, and applied to

arcaded designs as

well

as to peristyles and other open

colonnades. The marriage of the column and

arch

gave

birth to a system of forms as

characteristic of Roman architecture as

the Doric

or

Ionic colonnade is of the Greek.

THE

ROMAN ORDERS. To

meet the demands of Roman

taste the Etruscan column

was

retained with its simple

entablature; the Doric and Ionic were

adopted in a

modified

form; the Corinthian was developed into a

complete and independent

order,

and

the Composite was added to the

list. A regular system of

proportions for all

these

five orders was gradually

evolved, and the mouldings were

profiled with arcs of

circles

instead of the subtler Greek

curves. In the building of many-storied

structures

the

orders were superposed, the

more slender over the

sturdier, in an orderly and

graded

succession. The immense extent and number

of the Roman buildings, the

coarse

materials often used, the

relative scarcity of highly trained

artisans, and above

all,

the necessity of making a given amount of

artistic design serve for the

largest

possible

amount of architecture, combined to

direct the designing of detail

into

uniform

channels. Thus in time was

established a sort of canon of

proportions, which

was

reduced to rules by Vitruvius, and

revived in much more detailed and

precise

form

by Vignola in the sixteenth

century.

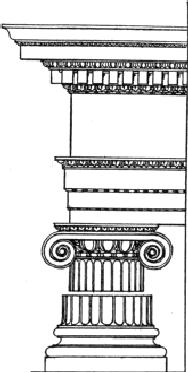

FIG.

43.--ROMAN IONIC ORDER.

In

each of the orders, including the

Doric, the column was given a

base one half of a

diameter

in height (the unit of measurement

being the diameter of the lower part

of

the

shaft, the crassitudo

of

Vitruvius). The shaft was

made to contract about

one-

sixth

in diameter toward the capital, under

which it was terminated by an astragal

or

collar

of small mouldings; at the base it

ended in a slight flare and

fillet called the

cincture. The

entablature was in all cases

given not far from one quarter the

height of

the

whole column. The Tuscan

order

was a rudimentary or Etruscan

Doric with a

column

seven diameters high and a simple

entablature without triglyphs, mutules,

or

dentils.

But few examples of its use

are known. The Doric

(Fig.

42) retained the

triglyphs

and metopes, the mutules and gutt� of the

Greek; but the column was

made

eight diameters high, he

shaft was smooth or had deep

flutings separated by

narrow

fillets, and was usually

provided with a simple moulded

base on a square

plinth.

Mutules were used only over the

triglyphs, and were even

replaced in some

cases

by dentils; the corona was

made lighter than the Greek, and a

cymatium

replaced

the antefix� on the lateral cornices. The

Ionic underwent fewer

changes,

and

these principally in the smaller

mouldings and details of the capital. The

column

was

nine diameters high (Fig. 43). The

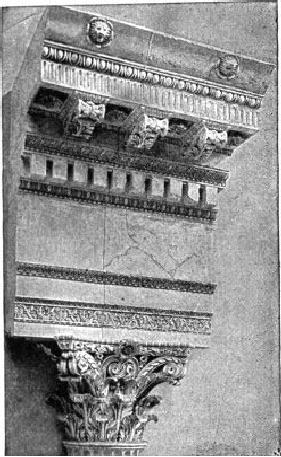

Corinthian

was

made into an independent

order

by the designing of a special base of

small tori

and

scoti�, and by

sumptuously

carved

modillions

or

brackets enriching the cornice and

supporting the corona

above

a

denticulated bed-mould (Fig. 44). Though

the first designers of the modillion

were

probably

Greeks, it must, nevertheless, be taken

as really a Roman device,

worthily

completing

the essentially Roman Corinthian

order. The Composite

was

formed by

combining

into one capital portions of the Ionic

and Corinthian, and giving to it a

simplified

form of the Corinthian cornice. The

Corinthian order remained,

however,

the

favorite order of Roman

architecture.

FIG.

44.--CORINTHIAN ORDER (TEMPLE OF

CASTOR AND POLLUX).

USE

OF THE ORDERS. The

Romans introduced many innovations in the

general use

and

treatment of the orders. Monolithic

shafts were preferred to

those built up of

superposed

drums. The fluting was omitted on these,

and when hard and semi-

precious

stone like porphyry or verd-antique

was the material, it was highly

polished

to

bring out its color. These

polished monoliths were

often of great size, and

they

were

used in almost incredible

numbers.

Another

radical departure from Greek

usage was the mounting of columns

on

pedestals

to secure greater height without

increasing the size of the column and

its

entablature.

The Greek anta

was

developed into the Roman pilaster or

flattened wall-

column,

and every free column, or range of

columns perpendicular to the fa�ade,

had

its

corresponding pilaster to support the

wall-end of the architrave. But the

most

radical

innovation was the general

use of engaged columns as

wall-decorations or

buttresses.

The engaged column projected from the wall by

more than half its

diameter,

and was built up with the wall as a part of its

substance (Fig. 45). The

entablature

was in many cases advanced only

over the columns, between which

it

was

set back almost to the plane

of the wall. This practice is open to the

obvious

criticism

that it makes the column appear

superfluous by depriving it of its

function

of

supporting the continuous entablature.

The objection has less

weight when the

projecting

entablature over the column serves as a

pedestal for a statue or

similar

object,

which restores to the column its function as a

support (see the Arch of

Constantine,

Fig.

63).

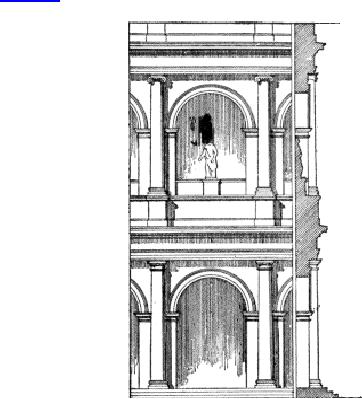

FIG.

45.--ROMAN ARCADE WITH ENGAGED

COLUMNS

(From

the Colosseum.)

ARCADES.

The

orders, though probably at first

used only as free supports

in

porticos

and colonnades, were early

applied as decorations to arcaded

structures.

This

practice became general with the

multiplication of many-storied arcades

like

those

of the amphitheatres, the engaged columns

being set between the arches

as

buttresses,

supporting entablatures which marked the

divisions into stories (Fig.

45).

This

combination has been

assailed as a false and illogical

device, but the criticism

proceeds

from a too narrow conception of

architectural propriety. It is

defensible

upon

both artistic and logical grounds; for it

not only furnishes a most desirable

play

of

light and shade and a pleasing contrast

of rectangular and curved lines, but

by

emphasizing

the constructive divisions and elements

of the building and the vertical

support

of the piers, it also contributes to the

expressiveness and vigor of the

design.

VAULTING.

The

Romans substituted vaulting in

brick, concrete, or masonry

for

wooden

ceilings wherever possible, both in

public and private edifices. The

Etruscans

were

the first vault-builders, and the Cloaca

Maxima, the great sewer of

Republican

Rome

(about 500 B.C.) still

remains as a monument of their engineering

skill.

Probably

not only Etruscan engineers (whose

traditions were perhaps

derived from

Asiatic

sources in the remote past), but

Asiatic builders also from

conquered eastern

provinces,

were engaged together in the

development of the wonderful system

of

vaulted

construction to which Roman architecture

so largely owed its

grandeur.

Three

types of vault were commonly

used: the barrel-vault, the groined or

four-part

vault,

and the dome.

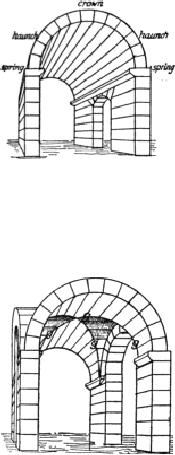

FIG.

46.--BARREL VAULT.

The

barrel vault (Fig. 46) was

generally semi-cylindrical in section,

and was used to

cover

corridors and oblong halls,

like the temple-cellas, or was

bent around a curve,

as

in amphitheatre passages.

FIG.

47.--GROINED VAULT.

g,

g, Groins.

The

groined vault is formed by the

intersection of two barrel-vaults (Fig.

47). When

several

compartments of groined vaulting

are placed together over an

oblong plan,

a

double advantage is secured.

Lateral windows can be carried up to the

full height

of

the vaulting instead of being

stopped below its springing;

and the weight and

thrust

of the vaulting are concentrated upon a

number of isolated points instead

of

being

exerted along the whole extent of the

side walls, as with the barrel-vault.

The

Romans

saw that it was sufficient to

dispose the masonry at these

points in masses

at

right angles to the length of the hall, to

best resist the lateral thrust of the

vault.

The

dome was in almost all Roman

examples supported on a circular wall

built up

four

or eight arches over a

square or octagonal plan, is not found in true

Roman

buildings.

The

Romans made of the vault something

more than a mere constructive

device. It

became

in their hands an element of interior

effect at least equally

important with

the

arch and column. No style of architecture

has ever evolved nobler

forms of

ceiling

than the groined vault and the dome.

Moreover, the use of vaulting

made

possible

effects of unencumbered spaciousness and

amplitude which could never

be

compassed

by any combination of piers and columns.

It also assured to the

Roman

monuments

a duration and a freedom from danger of

destruction by fire

impossible

with

any wooden-roofed architecture, however

noble its form or careful

its execution.

CONSTRUCTION.

The

constructive methods of the Romans

varied with the

conditions

and resources of different provinces, but

were everywhere dominated

by

the

same practical spirit. Their

vaulted architecture demanded for the

support of its

enormous

weights and for resistance to its

disruptive thrusts, piers and

buttresses of

great

mass. To construct these wholly of cut

stone appeared preposterous

and

wasteful

to the Roman. Italy abounds in clay,

lime, and a volcanic product,

pozzolana

(from

Puteoli or Pozzuoli, where it

has always been obtained in

large quantities),

which

makes an admirable hydraulic

cement. With these materials it

was possible to

employ

unskilled labor for the great bulk of

this massive masonry, and to erect

with

the

greatest rapidity and in the most

economical manner those

stupendous piles

which,

even in their ruin, excite the admiration

of every beholder.

FIG.

48.--ROMAN WALL MASONRY.

a,

Brickwork; b, Tufa ashlar; r,

Opus reticulatum; i, Opus

incertum.

STONE,

CONCRETE, AND BRICK MASONRY. For

buildings of an externally

decorative

character such as temples,

arches of triumph, and amphitheatres, as

well

as

in all places where brick and

concrete were not easily

obtained, stone was

employed.

The walls were built by laying up the

inner and outer faces in ashlar

or

cut

stone, and filling in the intermediate

space with rubble (random

masonry of

uncut

stone) laid up in cement, or with

concrete of broken stone and

cement dumped

into

the space in successive layers. The

cement converted the whole into

a

conglomerate

closely united with the face-masonry. In

Syria and Egypt the

local

preference

for stones of enormous size

was gratified, and even

surpassed, as in

Herod's

terrace-walls for the temple at

Jerusalem, and in the splendid structures

of

Palmyra

and Baalbec. In Italy, however, stones of

moderate size were

preferred, and

when

blocks of unusual dimensions occur, they

are in many cases marked with

false

joints,

dividing them into apparently smaller

blocks, lest they should dwarf

the

building

by their large scale. The general

use in the Augustan period of

marble for a

decorative

lining or wainscot in interiors

led in time to the objectionable

practice of

coating

buildings of concrete with an apparel of

sham marble masonry, by

carving

false

joints upon an external veneer of thin

slabs of that material. Ordinary

concrete

walls

were frequently faced with

small blocks of tufa, called,

according to the manner

of

its application, opus

reticulatum,

opus

incertum,

opus

spicatum,

etc. (Fig. 48). In

most

cases, however, the facing

was of carefully executed

brickwork, covered

sometimes

by a coating of stucco. The bricks

were large, measuring from

one to two

feet

square where used for quoins

or arches, but triangular where they

served only as

facings.

Bricks were also used in the

construction of skeleton ribs for

concrete vaults

of

large span.

VAULTING.

Here,

as in the wall-masonry, economy and

common sense devised

methods

extremely simple for accomplishing

vast designs. While the

smaller vaults

were,

so to speak, cast in concrete upon

moulds made of rough boards,

the enormous

weight

of the larger vaults precluded their

being supported, while drying

or

"setting,"

upon timber centrings built up from the

ground. Accordingly, a skeleton

of

light

ribs was first built on

wooden centrings, and these

ribs, when firmly "set,"

became

themselves supports for intermediate

centrings on which to cast the

concrete

fillings

between the ribs. The whole vault, once

hardened, formed really a

monolithic

curved

lintel, exerting no thrust whatever, so

that the extraordinary precautions

against

lateral disruption practised by the

Romans were, in fact, in many

cases quite

superfluous.

DECORATION.

The

temple of Castor and Pollux in the

Forum (long miscalled

the

temple

of Jupiter Stator), is a typical

example of Roman architectural

decoration, in

which

richness was preferred to the

subtler refinements of design

(see Fig.

44).

The

splendid

figure-sculpture which adorned the Greek

monuments would have

been

inappropriate

on the theatres and therm� of Rome or the

provinces, even had

there

been

the taste or the skill to produce it.

Conventional carved ornament

was

substituted

in its place, and developed into a

splendid system of highly

decorative

forms.

Two principal elements appear in this

decoration--the acanthus-leaf, as

the

basis

of a whole series of wonderfully varied

motives; and symbolism,

represented

principally

by what are technically termed

grotesques--incongruous

combinations of

natural

forms, as when an infant's body

terminates in a bunch of foliage (Fig.

49).

Only

to a limited extent do we find true

sculpture employed as decoration, and

that

mainly

for triumphal arches or memorial

columns.

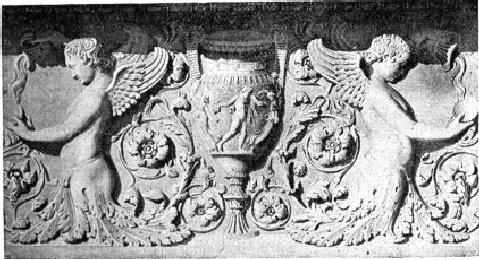

FIG.

49--ROMAN CARVED ORNAMENT.

(Lateran

Museum.)

The

architectural mouldings were

nearly always carved, the

Greek water-leaf and

egg-

and-dart

forming the basis of most of the

enrichments; but these were

greatly

elaborated

and treated with more minute detail than

the Greek prototypes.

Friezes

and

bands were commonly

ornamented with the foliated scroll or

rinceau

(a

convenient French term for which we have

no equivalent). This motive

was as

characteristic

of Roman art as the anthemion was of the

Greek. It consists of a

continuous

stem throwing out alternately on either

side branches which curl into

spirals

and are richly adorned with rosettes,

acanthus-leaves, scrolls, tendrils,

and

blossoms.

In the best examples the detail

was modelled with great care

and

minuteness,

and the motive itself was

treated with extraordinary variety and

fertility

of

invention. A derived and enriched form of

the anthemion was sometimes

used for

bands

and friezes; and grotesques, dolphins,

griffins, infant genii, wreaths,

festoons,

ribbons,

eagles, and masks are also

common features in Roman

relief carving.

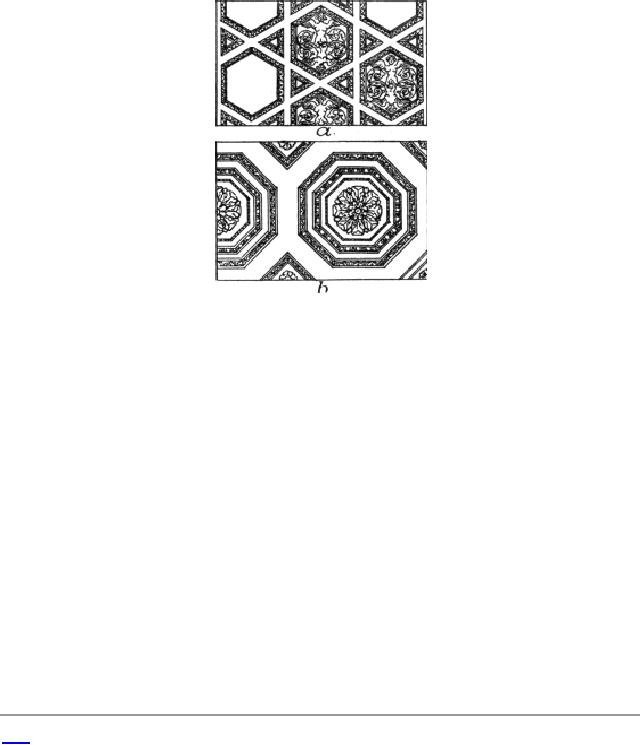

The

Romans made great use of

panelling and of moulded plaster in

their interior

decoration,

especially for ceilings. The panelling of

domes and vaults was

usually

roughly

shaped in their first

construction and finished afterward in

stucco with rich

moulding

and rosettes. The panels were not

always square or rectangular, as

in

Greek

ceilings, but of various geometric

forms in pleasing combinations

(Fig. 50). In

works

of a small scale the panels and

decorations were wrought in relief in a

heavy

coating

of plaster applied to the finished

structure, and these stucco

reliefs are

among

the most refined and charming

products of Roman art. (Baths of Titus;

Baths

at

Pompeii; Palace of the C�sars and

tombs at Rome.)

FIG.

50.--ROMAN CEILING PANELS.

(a,

From Palmyra; b,

Basilica of Constantine.)

COLOR

DECORATION. Plaster

was also used as a ground

for painting, executed in

distemper

or by the encaustic process, wax

liquefied by a hot iron being the

medium

for

applying the color in the latter

case. Pompeii and Herculaneum furnish

countless

examples

of brilliant wall-painting in which

strong primary colors form the

ground,

and

a semi-naturalistic, semi-fantastic

representation of figures, architecture

and

landscape

is mingled with festoons, vines, and

purely conventional ornament.

Mosaic

was

also employed to decorate

floors and wall-spaces, and sometimes for

ceilings.13

The

later imperial baths and

palaces were especially rich in

mosaic of the kind called

opus

Grecanicum, executed with numberless

minute cubes of stone or glass, as in

the

Baths

of Caracalla and the Villa of Hadrian at

Tivoli.

To

the walls of monumental interiors,

such as temples, basilicas, and

therm�,

splendor

of color was given by

veneering them with thin slabs of rare

and richly

colored

marble. No limit seems to have

been placed upon the costliness or amount

of

these

precious materials. Byzantine

architecture borrowed from this practice

its

system

of interior color

decoration.

13.

See

Van Dyke's History

of Paintings, p.

33.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.