|

GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION |

| << GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC |

| ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE >> |

CHAPTER

VII.

GREEK

ARCHITECTURE--Continued.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Same as for Chapter VI.

Also, Bacon and Clarke,

Investigations

at

Assos.

Espouy, Fragments

d'architecture antique.

Harrison and Verrall,

Mythology

and

Monuments of Ancient

Athens. Hitorff et

Zanth, Recueil

des Monuments de S�geste

et

S�linonte.

Magne, Le

Parth�non.

Koldewey and Puchstein,

Die

griechischen Tempel

in

Unteritalien und Sicilien.

Waldstein, The

Argive Her�um.

HISTORIC

DEVELOPMENT. The

history of Greek architecture,

subsequent to the

Heroic

or Primitive Age, may be divided into

periods as follows:

The

ARCHAIC; from 650 to 500 B.C.

The

TRANSITIONAL; from 500 to 460 B.C., or

to the revival of prosperity after

the

Persian

wars.

The

PERICLEAN; from 460 to 400 B.C.

The

FLORID or ALEXANDRIAN;

from 400 to 300 B.C.

The

DECADENT; 300 to 100 B.C.

The

ROMAN; 100 B.C. to 200 A.D.

These

dates are, of course,

somewhat arbitrary; it is impossible to

set exact bounds

to

style-periods, which must inevitably

overlap at certain points, but the

dates, as

given

above, will assist in distinguishing the

successive phases of the

history.

ARCHAIC

PERIOD. The

archaic period is characterized by the

exclusive use of the

Doric

order, which appears in the earliest

monuments complete in all its

parts, but

heavy

in its proportions and coarse in

its execution. The oldest known

temples of this

period

are the Apollo

Temple at

Corinth (650 B.C.?), and the Northern

Temple on

the

acropolis at Selinus

in

Sicily (cir. 610590 B.C.). They

are both of a coarse

limestone

covered with stucco. The columns

are low and massive (4⅓

to

4⅔

diameters

in height), widely spaced, and carry a

very high entablature. The

triglyphs

still

appear around the cella wall under the

pteroma ceiling, an illogical

detail

destined

to disappear in later buildings. Other

temples at Selinus date from

the

middle

or latter part of the sixth century; they

have higher columns and

finer profiles

than

those just mentioned. The great

Temple

of Zeus at

Selinus

was

the earliest of

five

colossal Greek temples of very

nearly identical dimensions; it

measured 360 feet

by

167 feet in plan, but was never

completed. During the second half of the

sixth

century

important Doric temples were

built at P�stum in South Italy,

and

Agrigentum

in Sicily; the somewhat primitive

temple at Assos in Asia Minor,

with

uncouth

carvings of centaurs and monsters on

its architrave, belongs to this

same

period.

The Temple

of Zeus at

Agrigentum

(Fig.

33) is another singular and

exceptional

design, and was the second of the

five colossal temples

mentioned above.

The

pteroma was entirely

enclosed by walls with engaged

columns showing

externally,

and was of extraordinary width. The walls

of the narrow cella were

interrupted

by heavy piers supporting

atlantes, or applied statues under the

ceiling.

There

seem to have been windows

between these figures, but it is not

clear whence

they

borrowed their light, unless it was

admitted by the omission of the

metopes

between

the external triglyphs.

FIG.

33.--TEMPLE OF ZEUS.

AGRIGENTUM.

THE

TRANSITION. During the

transitional period there

was a marked

improvement

in

the proportions, detail, and workmanship

of the temples. The cella was

made

broader,

the columns more slender, the

entablature lighter. The triglyphs

disappeared

from

the cella wall, and sculpture of a higher

order enhanced the architectural

effect.

The

profiles of the mouldings and especially

of the capitals became more

subtle and

refined

in their curves, while the development of the Ionic

order in important

monuments

in Asia Minor was preparing the way for

the splendors of the Periclean

age.

Three temples especially

deserve notice: the Athena

Temple on the

island of

�gina, the

Temple

of Zeus at

Olympia, and the

so-called Theseum--perhaps

a

temple

of Heracles--in Athens. They belong to

the period 470450 B.C.; they are

all

hexastyle

and peripteral, and without triglyphs on the

cella wall. Of the three the

second

in the list is interesting as the scene

of those rites which preceded

and

accompanied

the Panhellenic Olympian games, and as the

central feature of the

Altis,

the

most complete temple-group and

enclosure among all Greek

remains. It was built

of

a coarse conglomerate, finished with

fine stucco, and embellished with

sculpture

by

the greatest masters of the time. The

adjacent Heraion

(temple

of Hera) was a

highly

venerated and ancient shrine,

originally built with wooden columns

which,

according

to Pausanias, were replaced

one by one, as they decayed, by

stone

columns.

The truth of this statement is attested by the

discovery of a singular

variety

of

capitals among its ruins,

corresponding to the various periods at

which they were

added.

The Theseum is the most perfectly

preserved of all Greek temples, and in

the

refinement

of its forms is only surpassed by

those of the Periclean

age.

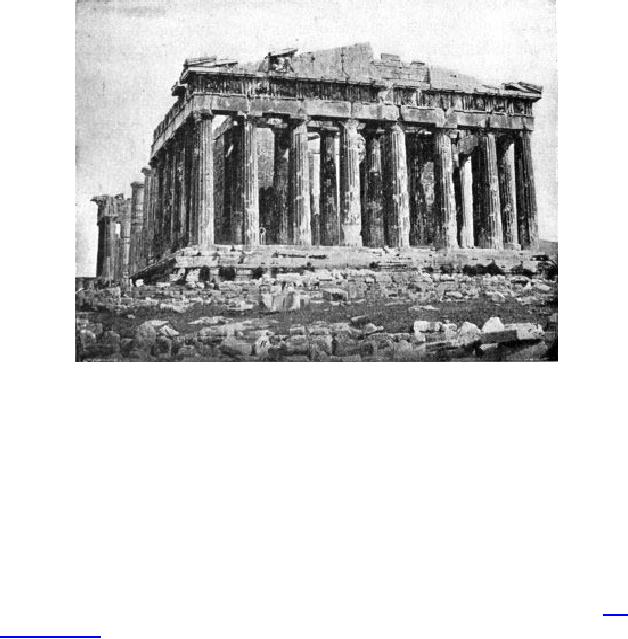

FIG.

34.--RUINS OF THE

PARTHENON.

THE

PERICLEAN AGE. The

Persian wars may be taken as the

dividing line between

the

Transition period and the Periclean

age. The �lan

of

national enthusiasm that

followed

the expulsion of the invader, and the

glory and wealth which accrued to

Athens

as the champion of all Hellas, resulted

in a splendid reconstruction of

the

Attic

monuments as well as a revival of

building activity in Asia Minor. By the

wise

administration

of Pericles and by the genius of Ictinus,

Phidias, and other artists

of

surpassing

skill, the Acropolis at Athens

was crowned with a group of

buildings and

statues

absolutely unrivalled. Chief

among them was the Parthenon, the

shrine of

Athena

Parthenos, which the critics of all

schools have agreed in

considering the

most

faultless in design and execution of all

buildings erected by man (Figs.

31,

34,

and

Frontispiece).

It was an octastyle peripteral

temple, with seventeen columns

on

the

side, and measured 220 by 100 feet on the

top of the stylobate. It was the

work

of

Ictinus and Callicrates, built to enshrine the

noble statue of the goddess

by

Phidias,

a standing chryselephantine figure forty

feet high. It was the

masterpiece of

Greek

architecture not only by reason of its

refinements of detail, but also

on

account

of the beauty of its sculptural

adornments. The frieze about the

cella wall

under

the pteroma ceiling, representing in low

relief with masterly skill

the

Panathenaic

procession; the sculptured groups in the

metopes, and the superb

assemblages

of Olympic and symbolic figures of

colossal size in the pediments,

added

their

majesty to the perfection of the

architecture.

Here

also the horizontal curvatures and

other refinements are found in

their highest

development.

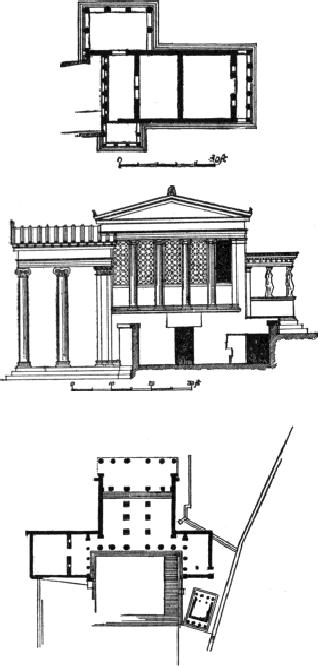

Northward from it, upon the Acropolis, stood the

Erechtheum,

an

excellent

example of the Attic-Ionic style

(Figs. 35, 36). Its singular

irregularities of

plan

and level, and the variety of its

detail, exhibit in a striking way the

Greek

indifference

to mere formal symmetry when

confronted by practical

considerations.

The

motive in this case was the

desire to include in one

design several existing

and

venerated

shrines to Attic deities and

heroes--Athena Polias, Poseidon,

Pandrosus,

Erechtheus,

Boutes, etc. Begun by unknown

architects in 479 B.C., and not

completed

until 408 B.C., it remains in its ruin

still one of the most

interesting and

attractive

of ancient buildings. Its two colonnades

of differing design, its

beautiful

north

doorway, and the unique and noble

caryatid porch or balcony on the

south

monument

of the Ionic order, the amphiprostyle

temple to Nike

Apteros--the

Wingless

Victory--stands on a projecting spur of

the Acropolis to the southwest. It

measures

only 27 feet by 18 feet in plan; the

cella is nearly square; the

columns are

sturdier

than those of the Erechtheum, and the

execution of the monument is

admirable.

It was the first completed of the

extant buildings of the group of

the

Acropolis

and dates from 466 B.C.

FIG.

35.--PLAN OF ERECHTHEUM.

FIG.

36.--WEST END OF ERECHTHEUM,

RESTORED.

FIG.

37.--PROPYL�A AT ATHENS.

PLAN.

In

the Propyl�a

(Fig.

37), the monumental gateway to the

Acropolis, the Doric and

Ionic

orders appear to have been

combined for the first time (437 to 432

B.C.). It

was

the master work of Mnesicles. The front and

rear fa�ades were Doric

hexastyles;

adjoining

the front porch were two projecting

lateral wings employing a

smaller Doric

order.

The central passageway led

between two rows of Ionic columns to the

rear

porch,

entered by five doorways and

crowned, like the front, with a pediment.

The

whole

was executed with the same

splendor and perfection as the other

buildings of

the

Acropolis, and was a worthy gateway to

the group of noble monuments

which

crowned

that citadel of the Attic capital. The

two orders were also

combined in the

temple

of Apollo

Epicurius at

Phigal�a

(Bass�).

This temple was erected in

430

B.C.

by Ictinus, who used the Ionic order

internally to decorate a row of

projecting

piers

instead of free-standing columns in the

naos, in which there was

also a single

Corinthian

column of rather archaic design, which

may have been used as a

support

for

a statue or votive

offering.

ALEXANDRIAN

AGE. A

period of reaction followed the

splendid architectural

activity

of the Periclean age. A succession of

disastrous wars--the Sicilian,

Peloponnesian,

and Corinthian--drained the energies and

destroyed the peace of

European

Greece for seventy-five years,

robbing Athens of her supremacy

and

inflicting

wounds from which she never recovered. In

the latter part of the fourth

century,

however, the triumph of the Macedonian

empire over all the

Mediterranean

lands

inaugurated a new era of architectural

magnificence, especially in Asia

Minor.

The

keynote of the art of this time was

splendor, as that of the preceding age

was

artistic

perfection. The Corinthian order

came into use, as though the Ionic were

not

rich

enough for the sumptuous taste of the

time, and capitals and bases of

novel and

elaborate

design embellished the Ionic temples of

Asia Minor. In the temple of Apollo

Didym�us

at Miletus,

the plinths of the bases were made

octagonal and panelled

with

rich scroll-carvings; and the piers which

buttressed the interior faces of

the

cella-walls

were given capitals of

singular but elegant form, midway between

the

Ionic

and Corinthian types. This

temple belongs to the list of

colossal edifices

already

referred

to; its dimensions were 366 by 163

feet, making it the largest of them

all.

The

famous Artemisium

(temple

of Artemis or Diana) measured 342 by 163

feet.

Several

of the columns of the latter were

enriched with sculptured figures

encircling

the

lower drums of the colossal

shafts.

The

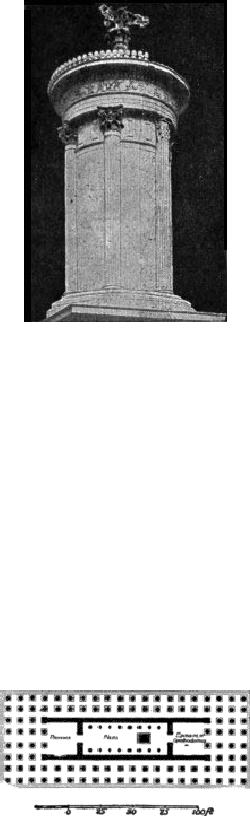

most lavish expenditure was

bestowed upon small structures,

shrines, and

sarcophagi.

The graceful monument still visible in

Athens, erected by the

choragus

Lysicrates

in token of his victory in the

choral competitions, belongs to this

period

(330

B.C.). It is circular, with a slightly

domical imbricated roof, and is

decorated

with

elegant engaged Corinthian

columns (Fig. 38). In the Imperial Museum

at

Constantinople

are several sarcophagi of this

period found at Sidon, but executed

by

Greek

artists, and of exceptional beauty. They

are in the form of temples or

shrines;

the

finest of them, supposed by some to

have been made for

Alexander's favorite

general

Perdiccas, and by others for the Persian

satrap who figures prominently

on

its

sculptured reliefs, is the most

sumptuous work of the kind in existence.

The

exquisite

polychromy of its beautiful

reliefs and the perfection of its rich

details of

cornice,

pediment, tiling, and crestings,

make it an exceedingly interesting

and

instructive

example of the minor architecture of the

period.

FIG.

38.--CHORAGIC

MONUMENT

OF LYSICRATES.

(Restored

model, N.Y.)

THE

DECADENCE. After

the decline of Alexandrian magnificence

Greek art never

recovered

its ancient glory, but the flame

was not suddenly extinguished.

While in

Greece

proper the works of the second and third

centuries B.C., are for the

most part

weak

and lifeless, like the Stoa

of Attalus (175

B.C.) and the Tower

of the Winds

(the

Clepsydra of Andronicus Cyrrhestes, 100

B.C.) at Athens or the Portico of

Philip

in

Delos, there were still a

few worthy works built in Asia Minor. The

splendid Altar

erected

at Pergamon

by

Eumenes II. (circ. 180 B.C.) in the Ionic

order, combined

sculpture

of extraordinary vigor with imposing

architecture in masterly fashion.

At

Aizanoi

an Ionic

Temple

to Zeus, by

some attributed to the Roman

period, but

showing

rather the character of good

late Greek work, deserves

mention for its

elegant

details, and especially for its

frieze-decoration of acanthus leaves and

scrolls

resembling

those of a Corinthian

capital.

FIG.

39.--TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN ZEUS.

ATHENS.

ROMAN

PERIOD. During this

period, i.e.,

throughout the second and first

centuries

B.C.,

the Roman dominion was

spreading over Greek

territory, and the structures

erected

subsequent to the conquest partake of the

Roman character and

mingle

Roman

conceptions with Greek details and

vice

vers�. The

temple of the Olympian

Zeus

at

Athens (Fig. 39), a mighty dipteral

Corinthian edifice measuring 354 by

171

feet,

standing on a vast terrace or

temenos surrounded by a buttressed wall,

was

begun

by Antiochus Epiphanes (170 B.C.) on the

site of an earlier unfinished

Doric

temple

of the time of Pisistratus, and carried

out under the direction of the

Roman

architect,

Cossutius. It was not, however, finally

completed until the time of

Hadrian,

130 A.D. Meanwhile Sulla had despoiled it

of several columns12 which

he

carried

to Rome (86 B.C.), to use in the

rebuilding of the temple of Jupiter on

the

Capitol,

where they undoubtedly served as

models in the development of the

Roman

Corinthian

order. The columns were 57

feet high, with capitals of the

most perfect

Corinthian

type; fifteen are now

standing, and one lies

prostrate near by. To the

Roman

period also belong the

Agora

Gate (circ.

35 B.C.), the Arch

of Hadrian (117

A.D.),

the Odeon

of Regilla or of

Herodes Atticus (143 A.D.), at

Athens, and many

temples

and tombs, theatres, arches,

etc., in the Greek

provinces.

SECULAR

MONUMENTS; PROPYL�A. The

stately gateway by which the

Acropolis

was

entered has already been

described. It was the noblest and

most perfect of a

class

of buildings whose prototype is found in

the monumental columnar porches

of

the

palace-group at Persepolis. The Greeks

never used the arch in these

structures,

nor

did they attach to them the same

importance as did most of the other

nations of

antiquity.

The Altis of Olympia, the national

shrine of Hellenism, appears to

have

had

no central gateway of imposing

size, but a number of insignificant

entrances

disposed

at random. The Propyl�a

of

Sunium,

Priene

and

Eleusis

are

the most

conspicuous,

after those of the Athenian

Acropolis. Of these the Ionic gateway

at

Priene

is the finest, although the later of the

two at Eleusis is interesting for its

anta-

capitals.

(Anta

= a flat

pilaster decorating the end of a

wing-wall and treated with a

base

and capital usually differing from

those of the adjacent columns.)

These are of

Corinthian

type, adorned with winged

horses, scrolls, and anthemions of

an

exuberant

richness of design, characteristic of

this late period.

COLONNADES,

STO�. These

were built to connect public

monuments (as the

Dionysiac

theatre and Odeon at Athens); or

along the sides of great

public squares,

as

at Assos and Olympia (the

so-called Echo

Hall); or as

independent open

public

halls,

as the Stoa

Diple at

Thoricus. They afforded shelter from sun

and rain, places

for

promenading, meetings with friends,

public gatherings, and similar

purposes.

They

were rarely of great size,

and most of them are of rather

late date, though the

archaic

structure at P�stum, known as the

Basilica,

was probably in reality an

open

hall

of this kind.

FIG.

40.--PLAN OF GREEK

THEATRE.

o,

Orchestra; l, Logeion; p, Paraskenai; s,

s, Stoa.

THEATRES,

ODEONS. These

were invariably cut out of the rocky

hillsides, though

in

a few cases (Mantin�a, Myra, Antiphellus)

a part of the seats were sustained by

a

built-up

substructure and walls to eke out the

deficiency of the hill-slope under

them.

The

front of the excavation was enclosed by a

stage and a set scene or

background,

built

up so as to leave somewhat over a

semicircle for the orchestra

or

space enclosed

by

the lower tier of seats

(Fig. 40). An altar to Dionysus

(Bacchus) was the

essential

feature

in the foreground of the orchestra, where

the Dionysiac choral dance

was

performed.

The seats formed successive

steps of stone or marble

sweeping around

the

sloping excavation, with carved

marble thrones for the priests,

archons, and

other

dignitaries. The only architectural

decoration of the theatre was that of the

set

scene

or skene, which with

its wing-walls (paraskenai)

enclosing the stage (logeion)

was

a permanent structure of stone or

marble adorned with doors,

cornices,

pilasters,

etc. This has perished in

nearly every case; but at

Aspendus, in Asia Minor,

there

is one still fairly well preserved, with

a rich architectural decoration on

its

inner

face. The extreme diameter of the

theatres varied greatly; thus at

Aizanoi it is

187

feet, and at Syracuse 495 feet. The

theatre of Dionysus at Athens

(finished 325

B.C.)

could accommodate thirty thousand

spectators.

The

odeon differed from the theatre

principally in being smaller and

entirely covered

in

by a wooden roof. The Odeon

of Regilla, built by

Herodes Atticus in Athens

(143

A.D.),

is a well-preserved specimen of this

class, but all traces of its

cedar ceiling and

of

its intermediate supports

have disappeared.

BUILDINGS

FOR ATHLETIC CONTESTS. These

comprised stadia and

hippodromes

for

races, and gymnasia and pal�str� for

individual exercise, bathing,

and

amusement.

The stadia

and

hippodromes

were

oblong enclosures surrounded by

tiers

of

seats and without conspicuous

architectural features. The

pal�stra

or

gymnasium--for the

terms are not clearly

distinguished--was a combination

of

courts,

chambers, tanks (piscin�) for

bathers and exedr�

or

semicircular recesses

provided

with tiers of seats for spectators and

auditors, destined not merely for

the

exercises

of athletes preparing for the stadium,

but also for the instruction and

diversion

of the public by recitations, lectures,

and discussions. It was the

prototype

of

the Roman therm�, but less

imposing, more simple in plan and

adornment. Every

Greek

city had one or more of them, but they

have almost wholly disappeared,

and

the

brief description by Vitruvius and

scanty remains at Alexandria

Troas and

Ephesus

furnish almost the only information we

possess regarding their form

and

arrangement.

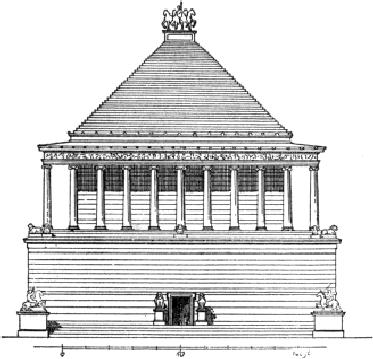

TOMBS.

These

are not numerous, and the most

important are found in Asia

Minor.

The

greatest of these is the famed

Mausoleum

at

Halicarnassus in Caria, the

monument

erected to the king Mausolus by

his widow Artemisia (354 B.C.;

Fig. 41).

It

was designed by Satyrus and

Pythius in the Ionic style, and comprised

a podium or

base

50 feet high and measuring 80 feet by 100

feet, in which was the

sepulchre.

Upon

this base stood a cella

surrounded by thirty-six Ionic columns;

and crowned by

a

pyramidal roof, on the peak of which

was a colossal marble

quadriga at a height of

130

feet. It was superbly

decorated by Scopas and other

great sculptors with

statues,

marble

lions, and a magnificent frieze. The

British Museum possesses fragments

of

this

most imposing monument. At Xanthus the

Nereid

Monument, so

called from its

sculptured

figures of Nereides, was a

somewhat similar design on a

smaller scale,

with

sixteen Ionic columns. At Mylassa

was another tomb with an open

Corinthian

colonnade

supporting a roof formed in a

stepped pyramid. Some of the

later rock-cut

tombs

of Lycia at Myra and Antiphellus may also

be counted as Hellenic

works.

FIG.

41.--MAUSOLEUM AT HALICARNASSUS.

(As

restored by the

author.)

DOMESTIC

ARCHITECTURE. This

never attained great

importance in Greece, and

our

knowledge of the typical Greek

house is principally derived from

literary sources.

Very

few remains of Greek houses

have been found sufficiently well

preserved to

permit

of restoring even the plan. It is

probable that they resembled in

general

arrangement

the houses of Pompeii but that they were

generally insignificant in

size

and

decoration. The exterior walls

were pierced only by the entrance

doors, all light

being

derived from one or more

interior courts. In the Macedonian

epoch there must

have

been greater display and luxury in

domestic architecture, but no remains

have

come

down to us of sufficient importance or

completeness to warrant further

discussion.

MONUMENTS.

In

addition to those already

mentioned in the text the

following should

be

enumerated:

PREHISTORIC PERIOD. In the Islands about

Santorin, remains of houses

antedating 1500

B.C.;

at Tiryns the Acropolis,

walls, and miscellaneous

ruins; the like also at

Mycen�,

besides

various tombs; walls and

gates at Samos, Thoricus,

Menidi, Athens, etc.

ARCHAIC PERIOD. Doric Temples at

Metapontium (by Durm assigned to 610

B.C.), Selinus,

Agrigentum,

P�stum; at Athens the first

Parthenon; in Asia Minor the

primitive Ionic

Artemisium

at Ephesus and the Heraion

at Samos, the latter the

oldest of colossal

Greek

temples.

TRANSITIONAL PERIOD.

At Agrigentum, temples of Concord,

Castor and Pollux,

Demeter,

�sculapius,

all circ. 480 B.C.; temples

at Selinus and

Segesta.

PERICLEAN PERIOD. In Athens the Ionic

temple on the Illissus,

destroyed during the

present

century;

on Cape Sunium the temple of

Athena, 430 B.C., partly

standing; at Nemea,

the

temple

of Zeus; at Tegea, the

temple of Athena Elea (400?

B.C.); at Rhamnus, the

temples

of

Themis and of Nemesis; at

Argos, two temples, stoa,

and other buildings; all

these

were

Doric.

ALEXANDRIAN PERIOD. The temple of Dionysus

at Teos; temple of Artemis

Leucophryne at

Magnesia,

both about 330 B.C. and of

the Ionic order.

DECADENCE AND ROMAN

PERIOD.

At Athens the Stoa of

Eumenes, circ. 170 B.C.;

the

monument

of Philopappus on the Museum

hill, 110 A.D.; the

Gymnasium of Hadrian,

114

to 137 A.D.; the last two of

the Corinthian order.

THEATRES.

Besides those already

mentioned there are

important remains of theatres

at

Epidaurus,

Argos, Segesta, Iassus (400?

B.C.), Delos, Sicyon, and

Thoricus; at Aizanoi,

Myra,

Telmissus, and Patara,

besides many others of less

importance scattered

through

the

Hellenic world. At Taormina

are extensive ruins of a

large Greek theatre rebuilt

in the

Roman

period.

12.

L.

Bevier, in Papers

of the American Classical

School at Athens (vol.

i., pp. 195,

196),

contends that these were

columns left from the old

Doric temple. This is

untenable,

for Sulla would certainly

not have taken the trouble

to carry away

archaic

Doric columns, with such

splendid Corinthian columns

before him.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.