|

GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC |

| << PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah |

| GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION >> |

CHAPTER

VI.

GREEK

ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Reber. Also,

Anderson and Spiers,

Architecture

of

Greece

and Rome.

Baumeister, Denkm�ler

der Klassischen

Alterthums.

B�tticher,

Tektonik

der Hellenen.

Chipiez, Histoire

critique des ordres grecs.

Curtius, Adler and

Treu,

Die

Ausgrabungen zu Olympia.

Durm, Antike

Baukunst (in

Handbuch

d. Arch.).

Frazer,

Pausanias'

Description of Greece.

Hitorff, L'architecture

polychrome chez

les

Grecs.

Michaelis, Der

Parthenon.

Penrose, An

Investigation, etc., of

Athenian

Architecture.

Perrot and Chipiez,

History

of Art in Primitive

Greece;

La

Gr�ce de

l'Epop�e;

La

Gr�ce archa�que.

Stuart and Revett, Antiquities

of Athens.

Tarbell, History

of

Greek Art.

Texier, L'Asie

Mineure.

Wilkins, Antiquities

of Magna Gr�cia.

GENERAL

CONSIDERATIONS. Greek

art marks the beginning of

European

civilization.

The Hellenic race gathered up

influences and suggestions from both

Asia

and

Africa and fused them with others,

whose sources are unknown, into an

art

intensely

national and original, which was to

influence the arts of many races

and

nations

long centuries after the

decay of the Hellenic states. The

Greek mind,

compared

with the Egyptian or Assyrian, was

more highly intellectual, more

logical,

more

symmetrical, and above all more

inquiring and analytic. Living

nowhere remote

from

the sea, the Greeks became

sailors, merchants, and colonizers. The

Ionian

kinsmen

of the European Greeks, speaking a

dialect of the same language,

populated

the

coasts of Asia Minor and many of the

islands, so that through them the

Greeks

were

open to the influences of the Assyrian,

Phoenician, Persian, and

Lycian

civilizations.

In Cyprus they encountered Egyptian

influences, and finally, under

Psammetichus,

they established in Egypt itself the

Greek city of Naukratis. They

were

thus by geographical situation, by

character, and by circumstances,

peculiarly

fitted

to receive, develop, and transmit the

mingled influences of the East and

the

South.

Olympiad,

776 B.C. The earliest monuments of that

historic architecture which

developed

into the masterpieces of the Periclean and

Alexandrian ages, date from

the

middle

of the following century. But there are a

number of older buildings,

belonging

presumably

to the so-called Heroic Age, which,

though seemingly unconnected with

the

later historic development of

Greek architecture, are

still worthy of note. They

are

the work of a people somewhat advanced in

civilization, probably the

Pelasgi,

who

preceded the Dorians on Greek

soil, and consist mainly of

fortifications, walls,

gates,

and tombs, the most important of which

are at Mycen�

and

Tiryns. At

the

latter

place is a well-defined acropolis, with

massive walls in which are

passages

covered

by stones successively overhanging or

corbelled until they meet. The

masonry

is of huge stones piled without

cement. At Mycen� the city wall is

pierced

by

the remarkable Lion

Gate (Fig.

22), consisting of two jambs and a huge

lintel,

over

which the weight is relieved by a

triangular opening. This is

filled with a

sculptured

group, now much defaced, representing two

rampant lions flanking

a

singular

column which tapers downward. This

symbolic group has relations

with

Hittite

and Phrygian sculptures, and with the

symbolism of the worship of

Rhea

Cybele.

The masonry of the wall is carefully

dressed but not regularly coursed.

Other

primitive

walls and gates showing

openings and embryonic arches of

various forms,

are

found widely scattered, at Samos and

Delos, at Phigaleia, Thoricus,

Argos and

many

other points.

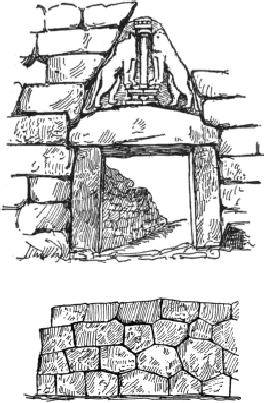

FIG.

22.--LION GATE AT MYCEN�.

FIG.

23.--POLYGONAL MASONRY.

The

very earliest are hardly more than

random piles of rough stone.

Those which

may

fairly claim notice for their artistic

masonry are of a later date

and of two kinds:

the

coursed, and the polygonal or Cyclopean,

so called from the tradition that

they

were

built by the Cyclopes. These Cyclopean

walls were composed of

large, irregular

polygonal

blocks carefully fitted

together and dressed to a fairly smooth

face (Fig.

23).

Both kinds were used

contemporaneously, though in the course of

time the

regular

coursed masonry finally superseded the

polygonal.

THOLOS

OF ATREUS. All

these structures present,

however, only the rudiments of

architectural

art. The so-called Tholos

(or

Treasury) of Atreus, at

Mycen�, on the

other

hand, shows the germs of truly artistic

design (Fig. 24). It is in reality a

tomb,

and

is one of a large class of

prehistoric tombs found in almost

every part of the

globe,

consisting of a circular stone-walled and

stone-roofed chamber buried under

a

tumulus

of earth. This one is a

beehive-shaped construction of horizontal

courses of

masonry,

with a stone-walled passage, the

dromos,

leading to the entrance

door.

Though

internally of domical form, its

construction with horizontal beds in

the

masonry

proves that the idea of the true dome

with the beds of each course

pitched

at

an angle always normal to the

curve of the vault, was not yet grasped.

A small

sepulchral

chamber opens from the great

one, by a door with the customary

relieving

triangle

over it.

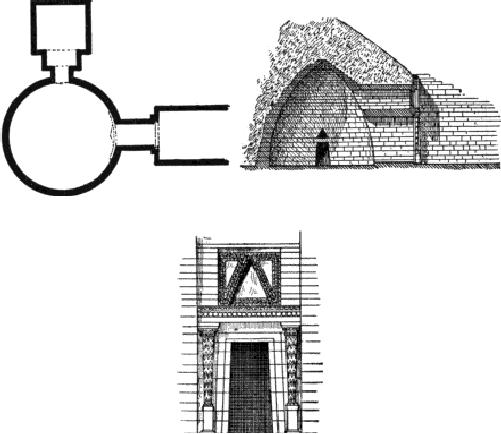

FIG.

24.--THOLOS OF ATREUS. PLAN AND

SECTION.

FIG.

25.--THOLOS OF ATREUS. DOORWAY.

Traces

of a metal lining have been

found on the inner surface of the dome and on

the

jambs

of the entrance door. This

entrance is the most artistic and

elaborate part of

the

edifice (Fig. 25). The main opening is

enclosed in a three-banded frame, and

was

once

flanked by columns which, as shown by

fragments still existing and by

marks

on

either side the door,

tapered downward as in the sculptured column

over the Lion

Gate.

Shafts, bases, and capitals

were covered with zig-zag

bands or chevrons of

fine

spirals.

This well-studied decoration, the

banded jambs, and the curiously

inverted

columns

(of which several other

examples exist in or near

Mycen�), all point to a

fairly

developed art, derived partly from

Egyptian and partly from Asiatic

sources.

That

Egyptian influences had affected this

early art is further proved by a

fragment

of

carved and painted ornament on a

ceiling in Orchomenos, imitating

with

remarkable

closeness certain ceiling

decorations in Egyptian

tombs.

HISTORIC

MONUMENTS; THE ORDERS. It

was the Dorians and Ionians

who

developed

the architecture of classic Greece.

This fact is perpetuated in

the

traditional

names, Doric and Ionic,

given to the two systems of columnar

design

which

formed the most striking

feature of that architecture. While in

Egypt the

column

was used almost exclusively

as an internal support and decoration, in

Greece

it

was chiefly employed to

produce an imposing exterior

effect. It was the

most

important

element in the temple architecture of the

Greeks, and an almost

indispensable

adornment of their gateways,

public squares, and temple

enclosures.

To

the column the two races named above

gave each a special and

radically distinct

development,

and it was not until the Periclean age that the two

forms came to be

used

in conjunction, even by the mixed

Doric-Ionic people of Attica.

Each of the two

types

had its own special shaft,

capital, entablature, mouldings, and

ornaments,

although

considerable variation was

allowed in the proportions and minor

details.

The

general type, however,

remained substantially unchanged from

first to last. The

earliest

examples known to us of either order show

it complete in all its parts,

its

later

development being restricted to the

refining and perfecting of its

proportions

and

details. The probable origin of

these orders will be separately

considered

later

on.

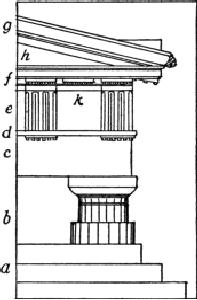

FIG.

26.--GREEK DORIC

ORDER.

A,

Crepidoma, or stylobate; b, Column; c,

Architrave; d, T�nia; e, Frieze; f,

Horizontal

cornice;

g, Raking cornice; h, Tympanum of

pediment; k, Metope.

THE

DORIC. The column of

the Doric order (Figs. 26, 27)

consists of a tapering

shaft

rising directly from the stylobate or

platform and surmounted by a capital

of

great

simplicity and beauty. The shaft is

fluted with sixteen to twenty

shallow

channellings

of segmental or elliptical section,

meeting in sharp edges or

arrises.

The

capital

is made up of a circular cushion or

echinus

adorned

with fine grooves

called

annul�, and a

plain square abacus

or

cap Upon this rests a plain

architrave or

epistyle, with a

narrow fillet, the t�nia, running

along its upper edge. The

frieze

above

it is divided into square panels,

called the metopes,

separated by vertical

triglyphs

having

each two vertical grooves and

chamfered edges. There is a

triglyph

over

each column and one over

each intercolumniation, or two in rare

instances

where

the columns are widely spaced. The

cornice consists of a broadly

projecting

corona

resting

on a bed-mould

of

one or two simple mouldings. Its under

surface,

called

the soffit, is

adorned with mutules,

square, flat projections having

each

eighteen

gutt�

depending

from its under side. Two or three

small mouldings run

along

the upper edge of the corona, which

has in addition, over each

slope of the

gable,

a gutter-moulding or cymatium. The

cornices along the horizontal

edges of the

roof

have instead of the cymatium a row of

antefix�,

ornaments of terra-cotta or

marble

placed opposite the foot of

each tile-ridge of the roofing. The

enclosed

triangular

field of the gable, called the

tympanum,

was in the larger

monuments

adorned

with sculptured groups resting on the

shelf formed by the horizontal

cornice

below.

Carved ornaments called

acroteria

commonly

embellished the three angles

of

the

gable or pediment.

POLYCHROMY.

It

has been fully proved, after

a century of debate, that all this

elaborate

system of parts, severe and

dignified in their simplicity of form,

received a

rich

decoration of color. While the

precise shades and tones

employed cannot be

predicated

with certainty, it is well established that the

triglyphs were painted

blue

and

the metopes red, and that all the

mouldings were decorated with

leaf-ornaments,

"eggs-and-darts,"

and frets, in red, green,

blue, and gold. The walls and

columns

were

also colored, probably with

pale tints of yellow or buff, to reduce the

glare of

the

fresh marble or the whiteness of the

fine stucco with which the surfaces

of

masonry

of coarser stone were

primed. In the clear Greek

atmosphere and outlined

against

the brilliant sky, the Greek temple must

have presented an aspect of

rich,

sparkling

gayety.

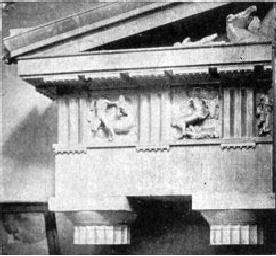

FIG.

27.--DORIC ORDER OF THE

PARTHENON.

ORIGIN

OF THE ORDER. It is

generally believed that the details of

the Doric frieze

and

cornice were reminiscences of a

primitive wood construction. The

triglyph

suggests

the chamfered ends of cross-beams

made up of three planks

each; the

mutules,

the sheathing of the eaves; and the

gutt�, the heads of the spikes

or

trenails

by which the sheathing was secured. It is

known that in early astylar

temples

the

metopes were left open like

the spaces between the ends of

ceiling-rafters. In the

earlier

peripteral temples, as at Selinus, the

triglyph-frieze is retained around

the

cella-wall

under the ceiling of the colonnade, where

it has no functional

significance,

as

a survival from times antedating the

adoption of the colonnade, when the

tradition

of

a wooden roof-construction showing

externally had not yet been

forgotten.

A

similar wooden origin for the

Doric column has been

advocated by some, who

point

to the assertion of Pausanias that in the

Doric Heraion at Olympia the

original

wooden

columns had with one exception

been replaced by stone

columns as fast as

they

decayed. This, however, only

proves that wooden columns

were sometimes used

in

early buildings, not that the Doric

column was derived from them. Others

would

derive

it from the Egyptian columns of Beni

Hassan, which it certainly resembles.

But

they

do not explain how the Greeks could

have been familiar with the

Beni Hassan

column

long before the opening of

Egypt to them under Psammetichus; nor

why,

granting

them some knowledge of Egyptian

architecture, they should have

passed

over

the splendors of Karnak and Luxor to copy

these inconspicuous tombs

perched

high

up on the cliffs of the Nile. It would

seem that the Greeks invented this

form

independently,

developing it in buildings which have

perished; unless, indeed,

they

brought

the idea with them from their primitive Aryan

home in Asia.

THE

IONIC ORDER was

characterized by greater slenderness of

proportion and

elegance

of detail than the Doric, and depended

more on carving than on color

for

the

decoration of its members

(Fig. 28). It was adopted in the fifth

century B.C. by

the

people of Attica, and used both for

civic and religious buildings,

sometimes alone

and

sometimes in conjunction with the Doric.

The column was from eight to ten

diameters

in height, against four and one-third to

seven for the Doric. It stood on

a

base

which was usually composed of two tori

separated by a scotia

(a

concave

moulding

of semicircular or semi-elliptical

profile), and was sometimes

provided also

with

a square flat base-block, the plinth.

There was much variety in the

proportions

and

details of these mouldings, which

were often enriched by

flutings or carved

guilloches.

The tall shaft bore twenty-four deep

narrow flutings separated by

narrow

fillets.

The capital was the most

peculiar feature of the order. It

consisted of a bead

or

astragal

and

echinus, over which was a

horizontal band ending on

either side in a

scroll

or volute, the sides of which presented

the aspect shown in Fig. 29. A

thin

moulded

abacus was interposed

between this member and the

architrave.

The

Ionic capital was marked by two awkward

features which all its richness

could

not

conceal. One was the protrusion of the

echinus beyond the face of the

band

above

it, the other was the disparity

between the side and front views of the

capital,

especially

noticeable at the corners of a colonnade.

To obviate this,

various

contrivances

were tried, none wholly

successful. Ordinarily the two adjacent

exterior

sides

of the corner capital were

treated alike, the scrolls at their

meeting being bent

out

at an angle of 45�, while the two inner faces

simply intersected, cutting

each

other

in halves.

FIG.

28.--GREEK IONIC ORDER.

(MILETUS.)

The

entablature comprised an architrave of

two or three flat bands crowned by

fine

mouldings;

an uninterrupted frieze, frequently

sculptured in relief; and a

simple

cornice

of great beauty. In addition to the

ordinary bed-mouldings there

was in most

examples

a row of narrow blocks or dentils

under the

corona, which was

itself

crowned

by a high cymatium of extremely graceful

profile, carved with the rich

"honeysuckle"

(anthemion)

ornament. All the mouldings were

carved with the "egg-

and-dart,"

heart-leaf and anthemion ornaments, so

designed as to recall by their

outline

the profile of the moulding itself. The

details of this order were

treated with

much

more freedom and variety than

those of the Doric. The pediments of

Ionic

buildings

were rarely or never adorned

with groups of sculpture. The volutes

and

echinus

of the capital, the fluting of the shaft, the

use of a moulded circular

base,

and

in the cornice the high corona and

cymatium, these were

constant elements in

every

Ionic order, but all other details

varied widely in the different

examples.

FIG.

29.--SIDE VIEW OF IONIC

CAPITAL.

ORIGIN

OF THE IONIC ORDER. The

origin of the Ionic order has

given rise to

almost

as much controversy as that of the Doric. Its

different elements

were

apparently

derived from various sources. The

Lycian tombs may have

contributed the

denticular

cornice and perhaps also the

general form of the column and capital.

In

the

Persian architecture of the sixth

century B.C., the high moulded

base, the narrow

flutings

of the shaft, the carved bead-moulding

and the use of scrolls in the

capital

are

characteristic features, which may have

been borrowed by the Ionians

during the

same

century, unless, indeed, they were

themselves the work of Ionic or

Lycian

workmen

in Persian employ. The banded

architrave and the use of the volute in

the

decoration

of stele-caps (from στηλη

=

a memorial stone or column standing

isolated

and

upright), furniture, and minor structures

are common features in

Assyrian,

Lycian,

and other Asiatic architecture of

early date. The volute or

scroll itself as an

independent

decorative motive may have

originated in successive variations

of

development

into the final form of the order was the work of the

Ionian Greeks, and

it

was in the Ionian provinces of Asia Minor

that the most splendid examples of

its

use

are to be found (Halicarnassus, Miletus,

Priene, Ephesus), while the

most

graceful

and perfect are those of

Doric-Ionic Attica.

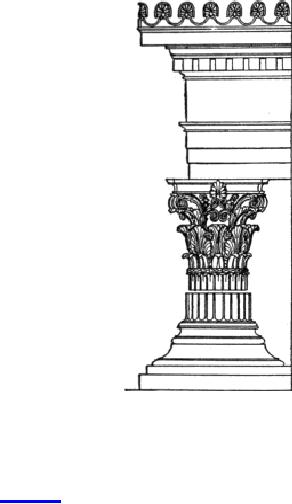

FIG.

30.--GREEK CORINTHIAN

ORDER.

(From

the monument of

Lysicrates.)

THE

CORINTHIAN ORDER. This

was a late outgrowth of the Ionic rather

than a

new

order, and up to the time of the Roman

conquest was only used for

monuments

of

small size (see Fig.

38).

Its entablature in pure Greek

examples was identical

with

the

Ionic; the shaft and base were only

slightly changed in proportion and

detail. The

capital,

however, was a new departure,

based probably on metallic

embellishments of

altars,

pedestals, etc., of Ionic style. It

consisted in the best examples of a high

bell-

shaped

core surrounded by one or two

rows of acanthus leaves,

above which were

pairs

of branching scrolls meeting at the

corners in spiral volutes.

These served to

support

the angles of a moulded abacus with

concave sides (Fig. 30). One

example,

from

the Tower of the Winds (the clepsydra of

Andronicus Cyrrhestes) at Athens,

has

only

smooth pointed palm-leaves and no

scrolls above a single row of

acanthus

leaves.

Indeed, the variety and disparity

among the different examples

prove that we

have

here only the first steps

toward the evolution of an independent

order, which it

was

reserved for the Romans to fully

develop.

GREEK

TEMPLES; THE TYPE. With the

orders as their chief

decorative element the

Greeks

built up a splendid architecture of

religious and secular monuments.

Their

noblest

works were temples, which they

designed with the utmost simplicity

of

general

scheme, but carried out with a mastery of

proportion and detail which

has

never

been surpassed. Of moderate

size in most cases, they

were intended

primarily

to

enshrine the simulacrum of the deity, and not,

like Christian churches,

to

accommodate

great throngs of worshippers. Nor

were they, on the other hand,

sanctuaries

designed, like those of

Egypt, to exclude all but a privileged

few from

secret

rites performed only by the priests and

king. The statue of the deity

was

enshrined

in a chamber, the naos

(see

plan, Fig. 31), often of

considerable size, and

accessible

to the public through a columnar porch

the pronaos. A

smaller chamber,

the

opisthodomus,

was sometimes added in the

rear of the main sanctuary, to

serve

as

a treasury or depository for votive

offerings. Together these

formed a windowless

structure

called the cella,

beyond which was the rear

porch, the posticum

or

epinaos.

This

whole structure was in the larger

temples surrounded by a colonnade,

the

peristyle, which

formed the most splendid

feature of Greek architecture. The

external

aisle

on either side of the cella

was called the pteroma. A

single gabled roof

covered

the

entire building.

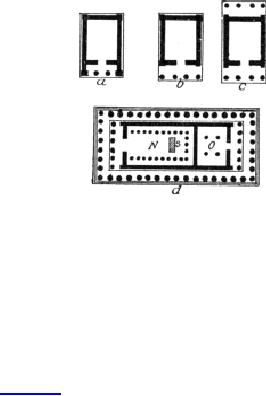

FIG.

31.--TYPES OF GREEK TEMPLE

PLANS.

a,

In Antis; b, Prostyle; c, Amphiprostyle;

d, Peripteral (The Parthenon); N,

Naos; O,

Opisthodomus;

S, Statue.

The

Greek colonnade was thus an

exterior feature, surrounding the

solid cella-wall

instead

of being enclosed by it as in Egypt. The

temple was a public, not a

royal

monument;

and its builders aimed, not as in

Egypt at size and overwhelming

sombre

majesty,

but rather at sunny beauty and the

highest perfection of

proportion,

There

were of course many variations of the

general type just described. Each

of

these

has received a special name,

which is given below with explanations

and is

illustrated

in Fig. 31.

In

antis; with a

porch having two or more

columns enclosed between the

projecting

side-walls

of the cella.

Prostylar

(or

prostyle); with a columnar porch in front

and no peristyle.

Amphiprostylar

(or

-style); with columnar porches at both

ends but no peristyle.

Peripteral;

surrounded by columns.

Pseudoperipteral; with

false or engaged columns built into the

walls of the cella,

leaving

no pteroma.

Dipteral; with

double lateral ranges of

columns (see Fig.

39).

Pseudodipteral; with a

single row of columns on each

side, whose distance from

the

wall

is equal to two intercolumniations of the

front.

Tetrastyle,

hexastyle,

octastyle,

decastyle,

etc.; with four, six, eight, or ten

columns in

the

end rows.

CONSTRUCTION.

All the

temples known to us are of stone, though

it is evident

from

allusions in the ancient writers that

wood was sometimes used in

early times.

The

finest temples, especially

those of Attica, Olympia, and

Asia Minor, were of

marble.

In Magna Gr�cia, at Assos, and in

other places where marble

was wanting,

limestone,

sandstone, or lava was

employed and finished with a thin, fine

stucco.

The

roof was almost invariably

of wood and gabled, forming at the

ends pediments

decorated

in most cases with sculpture. The

disappearance of these inflammable

and

perishable

roofs has given rise to

endless speculations as to the lighting

of the cellas,

which

in all known ruins, except one at

Agrigentum, are destitute of

windows. It has

been

conjectured that light was admitted

through openings in the roof, and even

that

the

central part of the cella was wholly

open to the sky. Such an arrangement

is

termed

hyp�thral, from an

expression used in a description by

Vitruvius;9

but

this

description

corresponds to no known structure, and the

weight of opinion now

inclines

against the use of the hyp�thral

opening, except possibly in

one or two of

the

largest temples, in which a part of the

cella in front of the statue may have

been

thus

left open. But even this partial

hyp�thros

is not

substantiated by direct

evidence.

It hardly seems probable that the

magnificent chryselephantine statues

of

such

temples were ever thus left

exposed to the extremes of the climate,

which are

often

severe even in Greece. In the

model of the Parthenon designed by Ch.

Chipiez

for

the Metropolitan Museum in New York, a small

clerestory opening through the

roof

admits a moderate amount of light to the

cella; but this ingenious device

rests

on

no positive evidence (see Frontispiece).

It seems on the whole most

probable that

the

cella was lighted entirely

by artificial illumination; but the

controversy in its

present

state is and must be wholly

speculative.

The

wooden roof was covered with

tiles of terra-cotta or marble. It

was probably

ceiled

and panelled on the under side, and richly

decorated with color and gold.

The

pteroma

had under the exterior roof a ceiling of

stone or marble, deeply

panelled

between

transverse architraves.

The

naos and opisthodomus being in the

larger temples too wide to

be spanned by

single

beams, were furnished with

interior columns to afford

intermediate support.

To

avoid the extremes of too

great massiveness and excessive

slenderness in these

columns,

they were built in two stages, and

advantage was taken of

this

arrangement,

in some cases, at least, to

introduce lateral galleries into the

naos.

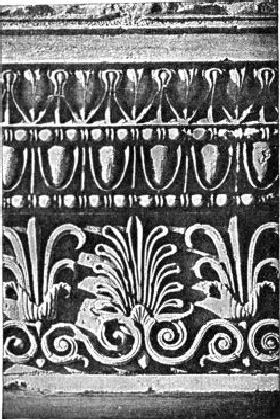

FIG.

32.--CARVED ANTHEMION ORNAMENT.

ATHENS.

SCULPTURE

AND CARVING. All the

architectural membering was

treated with the

greatest

refinement of design and execution, and

the aid of sculpture, both in

relief

and

in the round, was invoked to give

splendor and significance to the

monument.

The

statue of the deity was the

focus of internal interest, while

externally, groups of

statues

representing the Olympian deities or the

mythical exploits of gods,

demigods,

and

heroes, adorned the gables.

Relief carvings in the friezes and

metopes

commemorated

the favorite national myths. In these

sculptures we have the

finest

known

adaptations of pure sculpture--i.e.,

sculpture treated as such and

complete in

itself--to

an architectural framework. The noblest

examples of this decorative

sculpture

are those of the Parthenon,

consisting of figures in the full round from

the

pediments,

groups in high relief from the metopes,

and the beautiful frieze of the

Panathenaic

procession from the cella-wall under the

pteroma ceiling. The

greater

part

of these splendid works are

now in the British Museum, whither they

were

removed

by Lord Elgin in 1801. From

Olympia, �gina, and Phigaleia,

other master-

works

of the same kind have been

transferred to the museums of Europe. In

the

Doric

style there was little

carving other than the sculpture, the

ornament being

mainly

polychromatic. Greek Ionic and Corinthian

monuments, however, as well as

minor

works such as steles,

altars, etc., were richly

adorned with carved

mouldings

and

friezes, festoons, acroteria, and

other embellishments executed with the

chisel.

The

anthemion ornament, a form related to the

Egyptian lotus and

Assyrian

palmette,

most frequently figures in

these. It was made into

designs of wonderful

vigor

and beauty (Fig. 32).

DETAIL

AND EXECUTION. In the

handling and cutting of stone the

Greeks

displayed

a surpassing skill and delicacy.

While ordinarily they were

content to use

stones

of moderate size, they never

hesitated at any dimension necessary for

proper

effect

or solid construction. The lower drums of

the Parthenon peristyle are 6

feet

6�

inches in diameter, and 2 feet 10

inches high, cut from single

blocks of Pentelic

marble.

The architraves of the Propyl�a at Athens

are each made up of two

lintels

placed

side by side, the longest 17

feet 7 inches long, 3 feet

10 inches high, and

2

feet 4 inches thick. In the colossal

temples of Asia Minor, where the

taste for the

vast

and grandiose was more

pronounced, blocks of much greater

size were used.

These

enormous stones were cut and

fitted with the most scrupulous

exactness. The

walls

of all important structures were built in

regular courses throughout,

every stone

carefully

bedded with extremely close

joints. The masonry was

usually laid up

without

cement and clamped with metal;

there is no filling in with rubble

and

concrete

between mere facings of cut

stone, as in most modern work. When the

only

available

stone was of coarse texture

it was finished with a coating of

fine stucco, in

which

sharp edges and minute detail

could be worked.

The

details were, in the best

period, executed with the most

extraordinary refinement

and

care. The profiles of capitals and

mouldings, the carved ornament, the

arrises of

the

flutings, were cut with marvellous

precision and delicacy. It has

been rightly said

that

the Greeks "built like Titans and

finished like jewellers." But this

perfect finish

was

never petty nor wasted on unworthy or

vulgar design. The just relation of

scale

between

the building and all its parts

was admirably maintained; the

ornament was

distributed

with rare judgment, and the vigor of

its design saved it from

all

appearance

of triviality.

The

sensitive taste of the Greeks

led them into other refinements than

those of mere

mechanical

perfection. In the Parthenon especially,

but also in lesser degree in

other

temples,

the seemingly straight lines of the

building were all slightly

curved, and the

vertical

faces inclined. This was

done to correct the monotony and

stiffness of

absolutely

straight lines and right angles, and

certain optical illusions which

their

acute

observation had detected. The long

horizontal lines of the stylobate and

cornice

were

made convex upward; a similar

convexity in the horizontal corona of

the

pediment

counteracted the seeming concavity

otherwise resulting from its

meeting

with

the multiplied inclined lines of the

raking cornice. The columns

were almost

imperceptibly

inclined toward the cella, and the

corner intercolumniations made

a

trifle

narrower than the rest; while the

vertical lines of the arrises of the

flutings were

made

convex outward with a curve of the utmost

beauty and delicacy. By these

and

other

like refinements there was

imparted to the monument an elasticity and

vigor of

aspect,

an elusive and surprising beauty

impossible to describe and not to

be

explained

by the mere composition and general

proportions, yet manifest to

every

cultivated

eye.10

7.

For

enlargement on this topic

see Appendix

A.

8.

As

contended by W. H. Goodyear in his

Grammar

of the Lotus.

9.

Lib.

III., Cap. I.

10.

These

refinements, first noticed by

Allason in 1814, and later

confirmed by

Cockerell

and Haller as to the

columns, were published to

the world in 1838 by

Hoffer,

verified by Penrose in 1846, and

further developed by the

investigations of

Ziller

and later observers.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.