|

PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah |

| << CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS |

| GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC >> |

CHAPTER

V.

PERSIAN,

LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Babelon; Bliss,

Excavations

at Jerusalem.

Reber.

Also

Dieulafoy, L'Art

antique de la Perse.

Fellows, Account

of Discoveries in Lycia.

Fergusson,

The

Temple at Jerusalem.

Flandin et Coste, Perse

ancienne.

Perrot and

Chipiez,

History

of Art in Persia;

History

of Art in Phrygia, Lydia,

Caria, and Lycia;

History

of Art in Sardinia and

Jud�a.

Texier, L'Arm�nie

et la Perse;

L'Asie

Mineure.

De

Vog��,

Le

Temple de J�rusalem.

PERSIAN

ARCHITECTURE. With the

Persians, who under Cyrus (536 B.C.)

and

Cambyses

(525 B.C.) became the masters of the

Orient, the Aryan race

superseded

the

Semitic, and assimilated in new

combinations the forms it borrowed from

the

Assyrian

civilization. Under the Ach�menid� (536 to 330

B.C.) palaces were

built

in

Persepolis and Susa of a splendor and

majesty impossible in Mesopotamia,

and

rivalling

the marvels in the Nile Valley. The

conquering nation of warriors who

had

overthrown

the Egyptians and Assyrians was in turn

conquered by the arts of

its

vanquished

foes, and speedily became the

most luxurious of all nations. The

Persians

were

not great innovators in art; but

inhabiting a land of excellent building

resources,

they

were able to combine the

Egyptian system of interior

columns with details

borrowed

from Assyrian art, and suggestions,

derived most probably from the

general

use

in Persia and Central Asia, of

wooden posts or columns as

intermediate supports.

Out

of these elements they evolved an

architecture which has only become

fully

known

to us since the excavations of M. and Mme.

Dieulafoy at Susa in 1882.

ELEMENTS

OF PERSIAN ARCHITECTURE. The

Persians used both crude

and

baked

bricks, the latter far more

freely than was practicable in

Assyria, owing to the

greater

abundance of fuel. Walls when built of the

weaker material were faced

with

baked

brick enamelled in brilliant

colors, or both moulded and enamelled, to

form

colored

pictures in relief. Stone

was employed for walls and

columns, and, in

conjunction

with brick, for the jambs and lintels of

doors and windows.

Architraves

and

ceiling-beams were of wood. The

palaces were erected, as in

Assyria, upon broad

platforms,

partly cut in the rock and partly structural,

approached by imposing

flights

of steps. These palaces were

composed of detached buildings,

propyl�a or

gates

of honor, vast audience-halls open on

one or two sides, and chambers

or

dwellings

partly enclosing or flanking these

halls, or grouped in separate

buildings.

Temples

appear to have been of small

importance, perhaps owing to

habits of out-of-

door

worship of fire and sun. There

are few structural tombs, but

there are a number

of

imposing royal sepulchres cut in the

rock at Naksh-i-Roustam.

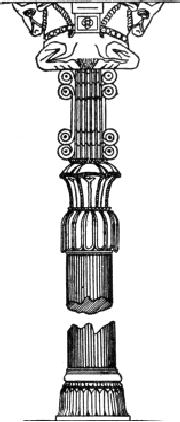

ARCHITECTURAL

DETAILS. The

Persians, like the Egyptians,

used the column as

an

internal feature in hypostyle

halls of great size, and

externally to form porches,

and

perhaps, also, open kiosks

without walls. The great Hall

of Xerxes at

Persepolis

covers

100,000 square feet--more than double the

area of the Hypostyle Hall at

Karnak.

But the Persian column was derived from

wooden prototypes and used

with

wooden

architraves, permitting a wider

spacing than is possible with stone. In

the

present

instance thirty-six columns

sufficed for an area which in the Karnak

hall

contained

one hundred and thirty-four. The shafts

being slender and finely fluted

instead

of painted or carved, the effect

produced was totally different from

that

sought

by the Egyptians. The most striking

peculiarity of the column was the

capital,

which

was forked (Fig. 21). In one

of the two principal types the fork,

formed by the

coupled

fore-parts of bulls or symbolic

monsters, rested directly on the top of

the

shaft.

In the other, two singular members were

interposed between the fork and

the

shaft;

the lower, a sort of double bell or

bell-and-palm capital, and above it,

just

beneath

the fork, a curious combination of

vertical scrolls or volutes,

resembling

certain

ornaments seen in Assyrian furniture. The

transverse architrave rested in

the

fork;

the longitudinal architrave was

supported on the heads of the monsters. A

rich

moulded

base, rather high and in some

cases adorned with carved

leaves or flutings,

supported

the columns, which in the Hall of Xerxes

were over 66 feet high and

6

feet

in diameter. The architraves have

perished, but the rock-cut tomb of Darius

at

Naksh-i-Roustam

reproduces in its fa�ade a

palace-front, showing a

banded

architrave

with dentils--an obvious imitation of the

ends of wooden rafters on

a

lintel

built up of several beams.

FIG.

21.--COLUMN FROM PERSEPOLIS.

These

features of the architrave, as well as the

fine flutings and moulded

bases of the

columns,

are found in Ionic architecture, and in

part, at least, in Lycian

tombs. As all

these

examples date from nearly the

same period, the origin of

these forms and their

mutual

relations have not been fully

determined. The Persian capitals,

however, are

unique,

and so far as known, without direct prototypes or

derivatives. Their

constituent

elements may have been

borrowed from various sources. One

can hardly

help

seeing the Egyptian palm-capital in the

lower member of the compound

type

(Fig.

21).

The

doors and windows had banded

architraves or trims and cavetto cornices

very

Egyptian

in character. The portals were

flanked, as in Assyria, by winged

monsters;

but

these were built up in several

courses of stone, not carved from

single blocks like

their

prototypes. Plaster or, as at Susa,

enamelled bricks, replaced as a

wall-finish

the

Assyrian alabaster wainscot.

These bricks, splendid in

color, and moulded into

relief

pictures covering large

surfaces, are the oldest

examples of the skill of the

Persians

in a branch of ceramic art in which they

have always excelled down to

our

own

day.

LYCIAN

ARCHITECTURE. The

architecture of those Asiatic

peoples which served

as

intermediaries between the ancient

civilizations of Egypt and Assyria on the

one

hand

and of the Greeks on the other, need

occupy us only a moment in

passing.

None

of them developed a complete and

independent style or produced

monuments

of

the first rank. Those chiefly

concerned in the transmission of ideas

were the

Cypriotes,

Phoenicians, and Lycians. The part played

by other Asiatic nations is

too

slight

to be considered here. From

Cyprus the Greeks could have

learned little

beyond

a few elementary notions regarding

sculpture and pottery, although it

is

possible

that the volute-form in Ionic architecture

was originally derived

from

patterns

on Cypriote pottery and from certain

Cypriote steles, where it

appears as a

modified

lotus motive. The Phoenicians

were the world's traders from a very

early

age

down to the Persian conquest. They not only

distributed through the

Mediterranean

lands the manufactures of Egypt and

Assyria, but also

counterfeited

them

and adopted their forms in decorating

their own wares. But they

have

bequeathed

us not a single architectural ruin of

importance, either of temples

or

palaces,

nor are the few tombs still

extant of sufficient artistic

interest to deserve

even

brief mention in a work of this

scope.

In

Lycia, however, there arose

a system of tomb-design which came

near creating a

new

architectural style, and which doubtless

influenced both Persia and the

Ionian

colonies.

The tombs were mostly cut in the

rock, though a few are

free-standing

monolithic

monuments, resembling sarcophagi or

small shrines mounted on a

high

base

or pedestal.

In

all of these tombs we recognize a

manifest copying in stone of

framed wooden

structures.

The walls are panelled, or

imitate open structures

framed of squared

timbers.

The roofs are often gabled,

sometimes in the form of a pointed arch;

they

generally

show a banded architrave, dentils, and a

raking cornice, or else

an

imitation

of broadly projecting eaves with

small round rafters. There

are several with

porches

of Ionic columns; of these, some

are of late date and

evidently copied from

Asiatic

Greek models. Others, and

notably one at Telmissus,

seem to be examples of

a

primitive Ionic, and may indeed have

been early steps in the

development of that

splendid

style which the Ionic Greeks, both in

Asia Minor and in Attica, carried

to

such

perfection.

JEWISH

ARCHITECTURE. The

Hebrews borrowed from the art of every

people with

whom

they had relations, so that we encounter in the few

extant remains of

their

architecture

Egyptian, Assyrian, Phoenician,

Greek, Roman, and

Syro-Byzantine

features,

but nothing like an independent

national style. Among the

most interesting

of

these remains are tombs of

various periods, principally

occurring in the valleys

near

Jerusalem, and erroneously ascribed by

popular tradition to the

judges,

prophets,

and kings of Israel. Some of them

are structural, some cut in the

rock; the

former

(tomb of Absalom, of Zechariah)

decorated with Doric and Ionic

engaged

orders,

were once supposed to be

primitive types of these

orders and of great

antiquity.

They are now recognized to be debased

imitations of late Greek work

of

the

third or second century B.C. They have

Egyptian cavetto cornices and

pyramidal

roofs,

like many Asiatic tombs. The

openings of the rock-cut tombs

have frames or

pediments

carved with rich surface ornament

showing a similar mixture of

types--

Roman

triglyphs and garlands, Syrian-Greek

acanthus leaves, conventional

foliage of

Byzantine

character, and naturalistic carvings of

grapes and local plant-life.

The

carved

arches of two of the ancient city gates

(one the so-called Golden

Gate) in

Jerusalem

display rich acanthus foliage

somewhat like that of the tombs, but

more

vigorous

and artistic. If of the time of Herod or

even of Constantine, as claimed

by

some,

they would indicate that Greek artists in

Syria created the prototypes

of

Byzantine

ornament. They are more

probably, however, Byzantine

restorations of the

6th

century A.D.

The

one great achievement of

Jewish architecture was the

national Temple

of

Jehovah,

represented by three successive

edifices on Mount Moriah, the site of

the

present

so-called "Mosque of Omar." The first,

built by Solomon (1012 B.C.)

(successive

courts, lofty entrance-pylons, the

Sanctuary and the sekos or "Holy

of

Holies")

with Phoenician and Assyrian details and

workmanship (cedar

woodwork,

empaistic

decoration or overlaying with repouss�

metal

work, the isolated brazen

columns

Jachin and Boaz). The whole stood on a

mighty platform built up with

stupendous

masonry and vaulted chambers from the

valley surrounding the rock

on

three

sides. This precinct was

nearly doubled in size by

Herod (18 B.C.) who

extended

it southward by a terrace-wall of still

more colossal masonry. Some

of the

stones

are twenty-two feet long;

one reaches the prodigious

length of forty feet. The

"Wall

of Lamentations" is a part of this terrace, upon which

stood the Temple on a

raised

platform. As rebuilt by Herod, the

Temple reproduced in part the

antique

design,

and retained the porch of Solomon

along the east side; but the whole

was

superbly

reconstructed in white marble with

abundance of gilding. Defended by

the

Castle

of Antonia on the northwest, and

embellished with a new and imposing

triple

colonnade

on the south, the whole edifice, a

conglomerate of Egyptian, Assyrian,

and

Roman

conceptions and forms, was

one of the most singular and yet

magnificent

creations

of ancient art.

The

temple of Zerubbabel (515 B.C.),

intermediate between those

above described,

was

probably less a re-edification of the

first, than a new design. While

based on the

scheme

of the first temple, it appears to

have followed more closely

the pattern

described

in the vision of Ezekiel (chapters

xl.-xlii.). It was far inferior to

its

predecessor

in splendor and costliness. No vestiges

of it remain.

MONUMENTS.

PERSIAN:

at Murghab, the tomb of

Cyrus, known as

Gabr�-Madr�-

Soleiman--a

gabled structure on a seven-stepped

pyramidal basement (525 B.C.).

At

Persepolis

the palace of Darius (521

B.C.); the Propyl�a of

Xerxes, his palace and

his

harem

(?) or throne-hall (480 B.C.).

These splendid structures,

several of them of

vast

size,

resplendent with color and

majestic with their singular

and colossal columns,

must

have

formed one of the most

imposing architectural groups in

the world. At various

points,

tower-like tombs, supposed

erroneously by Fergusson to have

been fire altars. At

Naksh-i-Roustam,

the tomb of Darius, cut in

the rock. Other tombs

near by at Persepolis

proper

and at Pasargad�. At the

latter place remains of the

palace of Cyrus. At Susa

the

palace

of Xerxes and Artaxerxes (480405

B.C.).

There

are no remains of private

houses or temples.

LYCIAN:

the principal Lycian

monuments are found in Myra,

Antiphellus, and

Telmissus.

Some

of the monolithic tombs have

been removed to the British

and other European

museums.

JEWISH:

the temples have been

mentioned above. The palace

of Solomon. The

rock-cut

monolithic

tomb of Siloam. So-called

tombs of Absalom and

Zechariah, structural;

probably

of Herod's time or later.

Rock-cut Tombs of the Kings;

of the Prophets, etc.

City

gates

(Herodian or early Christian

period).

6.

1

Kings vi.-vii.; 2 Chronicles

iii.-iv.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.