|

CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS |

| << EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS |

| PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah >> |

CHAPTER

IV.

CHALD�AN

AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Reber. Also,

Babelon, Manual

of Oriental

Antiquities.

Botta and Flandin, Monuments

de Ninive.

Layard, Discoveries

in Nineveh;

Nineveh

and its Remains.

Loftus, Travels

and Researches in Chald�a and

Susiana.

Perrot

and Chipiez, History

of Art in Chald�a and

Assyria.

Peters, Nippur.

Place,

Ninive

et l'Assyrie.

SITUATION;

HISTORIC PERIODS. The

Tigro-Euphrates valley was the

seat of a

civilization

nearly or quite as old as that of the

Nile, though inferior in

its

monumental

art. The kingdoms of Chald�a and Assyria

which ruled in this valley,

sometimes

as rivals and sometimes as subjects

one of the other, differed

considerably

in

character and culture. But the scarcity

of timber and the lack of good

building-

stone

except in the limestone table-lands and

more distant mountains of

upper

Mesopotamia,

the abundance of clay, and the flatness of the

country, imposed upon

the

builders of both nations similar

restrictions of conception, form, and

material.

Both

peoples, moreover, were

probably, in part at least, of Semitic

race.4 The

Chald�ans

attained civilization as early as 4000

B.C., and had for centuries

maintained

fixed institutions and practised the

arts and sciences when the

Assyrians

began

their career as a nation of conquerors by

reducing Chald�a to

subjection.

The

history of Chald�o-Assyrian art may be

divided into three main periods,

as

follows:

1.

The EARLY CHALD�AN,

4000 to 1250 B.C.

2.

The ASSYRIAN, 1250 to 606 B.C.

3.

The BABYLONIAN, 606 to 538 B.C.

In

538 the empire fell before the

Persians.

GENERAL

CHARACTER OF MONUMENTS. Recent

excavations at Nippur (Niffer),

the

sacred city of Chald�a, have

uncovered ruins older than the Pyramids.

Though of

slight

importance architecturally, they reveal

the early knowledge of the arch and

the

possession

of an advanced culture. The poverty of

the building materials of this

region

afforded only the most limited

resources for architectural effect. Owing

to the

flatness

of the country and the impracticability of building

lofty structures with sun-

dried

bricks, elevation above the

plain could be secured only by

erecting buildings of

moderate

height upon enormous mounds or

terraces, built of crude brick and

faced

with

hard brick or stone. This

led to the development of the stepped

pyramid as the

typical

form of Chald�o-Assyrian architecture. Thick

walls were necessary both

for

stability

and for protection from the burning heat

of that climate. The lack of

stone

for

columns and the difficulty of procuring

heavy beams for long spans

made broad

halls

and chambers impossible. The plans of

Assyrian palaces look like

assemblages

of

long corridors and small

cells (Fig. 18). Neither the

wooden post nor the column

played

any part in this architecture except for

window-mullions and subordinate

arch

was certainly employed for

doors and the barrel-vault for the

drainage-tunnels

under

the terraces, made necessary by the

heavy rainfall. What these

structures

lacked

in durability and height was

made up in decorative magnificence. The

interior

walls

were wainscoted to a height of

eight or nine feet with alabaster

slabs covered

with

those low-relief pictures of hunting

scenes, battles, and gods, which now

enrich

the

museums of London, Paris, and

other modern cities.

Elsewhere painted plaster

or

more

durable enamelled tile in

brilliant colors embellished the

walls, and, doubtless,

rugs

and tapestries added their

richness to this architectural

splendor.

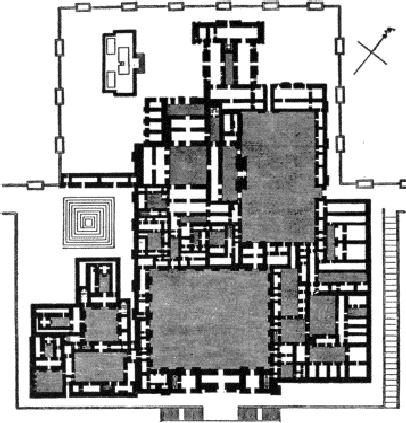

FIG.

18.--PALACE OF SARGON AT

KHORSABAD.

CHALD�AN

ARCHITECTURE. The ruins at

Mugheir (the Biblical Ur),

dating,

perhaps,

from 2200 B.C., belong to the two-storied

terrace or platform of a

temple

to

Sin or Hurki. The wall of sun-dried brick

is faced with enamelled tile. The

shrine,

which

was probably small, has

wholly disappeared from the summit of the

mound.

At

Warka (the ancient Erech)

are two terrace-walls of palaces,

one of which is

ornamented

with convex flutings and with a species

of mosaic in checker

patterns

and

zigzags, formed by terra-cotta

cones or spikes driven into the clay,

their exposed

bases

being enamelled in the desired

colors. The other shows a

system of long,

narrow

panels, in a style suggesting the

influence of Egyptian models through

some

as

yet unknown channel. This panelling

became a common feature of the

later

Assyrian

art (see Fig. 19). At Birs-Nimroud

are the ruins of a stepped

pyramid

surmounted

by a small shrine. Its seven

stages are said to have

been originally faced

with

glazed tile of the seven

planetary colors, gold,

silver, yellow, red, blue,

white,

and

black. The ruins at Nippur, which comprise

temples, altars, and dwellings

dating

from

4000 B.C., have been alluded

to. Babylon, the later capital of

Chald�a, to

which

the shapeless mounds of Mujehbeh and Kasr

seem to have belonged, has

left

no

other recognizable vestige of

its ancient

magnificence.

ASSYRIAN

ARCHITECTURE. Abundant

ruins exist of Nineveh, the Assyrian

capital,

and

its adjacent palace-sites.

Excavations at Koyunjik, Khorsabad, and Nimroud

have

laid

bare a number of these royal

dwellings. Among them are the

palace of Assur-

nazir-pal

(885 B.C.) and two palaces of Shalmaneser

II. (850 B.C.) at Nimroud; the

great

palace of Sargon at Khorsabad (721

B.C.); that of Sennacherib at

Koyunjik

(704

B.C.); of Esarhaddon at Nimroud (650

B.C.); and of Assur-bani-pal at

Koyunjik

(660

B.C.). All of these palaces

are designed on the same

general principle,

best

shown

by the plan (Fig. 18) of the palace of

Sargon at Khorsabad, excavated by

Botta

and

Place.

In

this palace two large and several

smaller courts are

surrounded by a complex

series

of long, narrow halls and small,

square chambers. One court

probably

belonged

to the harem, another to the king's

apartments, others to dependents

and

to

the service of the palace. The crude

brick walls are immensely

thick and without

windows,

the only openings being for doors. The

absence of columns made wide

halls

impossible,

and great size could only be

attained in the direction of

length.

A

terraced pyramid supported an

altar or shrine to the southwest of the

palace; at

the

west corner was a temple,

the substructure of which was crowned by

a cavetto

cornice

showing plainly the influence of Egyptian

models. The whole palace

stood

upon

a stupendous platform faced with cut

stone, an unaccustomed extravagance

in

Assyria.

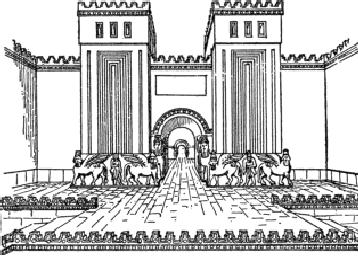

FIG.

19.--GATE, KHORSABAD.

ARCHITECTURAL

DETAILS. There

is no evidence that the Assyrians ever

used

columnar

supports except in minor or accessory

details. There are few halls

in any of

the

ruins too wide to be spanned by

good Syrian cedar beams or

palm timbers, and

these

few cases seem to have had

vaulted ceilings. So clumsy a

feature as the central

wall

in the great hall of Esarhaddon's palace

at Nimroud would never have

been

resorted

to for the support of the ceiling, had the

Assyrians been familiar with

the

use

of columns. That they understood the arch

and vault is proved by their

admirable

terrace-drains

and the fine arched gate in the

walls of Khorsabad (Fig. 19), as well

as

by

bas-reliefs representing dwellings with

domes of various forms.

Moreover, a few

vaulted

chambers of moderate size, and

fallen fragments of crude

brick vaulting of

larger

span, have been found in

several of the Assyrian ruins.

The

construction was extremely

simple. The heavy clay walls

were faced with

alabaster,

burned brick, or enamelled

tiles. The roofs were

probably covered with

stamped

earth, and sometimes paved on top with

tiles or slabs of alabaster to

form

terraces.

Light was introduced most

probably through windows immediately

under

the

roof and divided by small

columns forming mullions, as

suggested by certain

relief

pictures. No other system

seems consistent with the windowless

walls of the

ruins.

It is possible that many rooms depended

wholly on artificial light or on the

scant

rays coming through open

doors. To this day, in the hot season the

population

of

Mosul takes refuge from the torrid heats

of summer in windowless

basements

lighted

only by lamps.

ORNAMENT.

The only

structural decorations seem to

have been the panelling

of

exterior

walls in a manner resembling the

Chald�an terrace-walls, and a form

of

parapet

like a stepped cresting.

There were no characteristic

mouldings, architraves,

capitals,

or cornices. Nearly all the ornament

was of the sort called

applied,

i.e.,

added

after the completion of the structure

itself. Pictures in low relief

covered the

alabaster

revetment. They depicted hunting-scenes,

battles, deities, and

other

mythological

subjects, and are interesting to the

architect mainly for their

occasional

representations

of buildings and details of construction.

Above this wainscot

were

friezes

of enamelled brick ornamented with

symbolic forms used as

decorative

motives;

winged bulls, the "sacred

tree" and mythological monsters, with

rosettes,

palmettes,

lotus-flowers, and guilloches

(ornaments

of interlacing bands winding

about

regularly spaced buttons or

eyes). These ornaments were

also used on the

archivolts

around the great arches of

palace gates. The most

singular adornments of

these

gates were the carved "portal

guardians" set into the deep

jambs--colossal

monsters

with the bodies of bulls, the wings of

eagles, and human heads of

terrible

countenance.

Of mighty bulk, they were yet minutely wrought in

every detail of

head-dress,

beard, feathers, curly hair, and

anatomy.

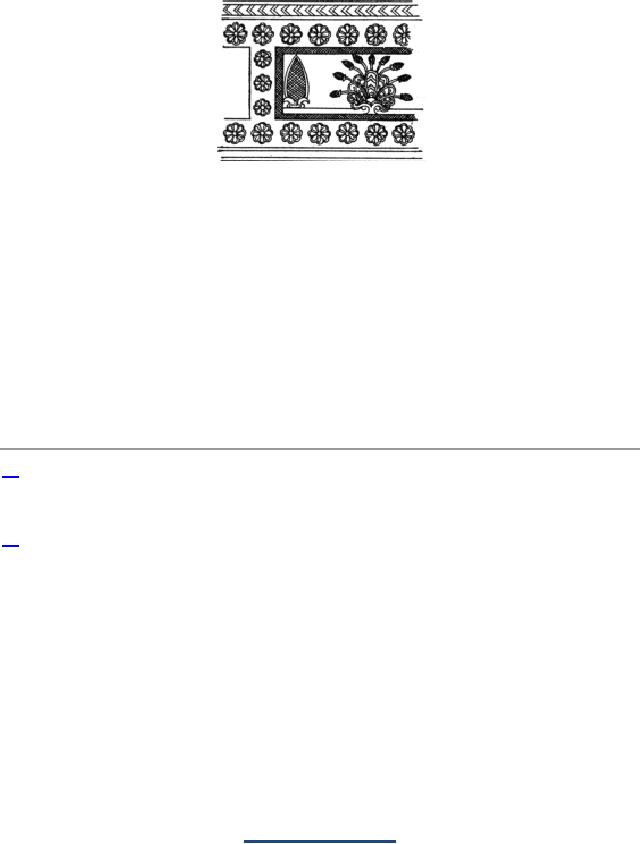

The

purely conventional ornaments mentioned

above--the rosette, guilloche,

and

lotus-flower,

and probably also the palmette,

were derived from Egyptian

originals.

They

were treated, however, in a

quite new spirit and adapted to the

special

materials

and uses of their environment. Thus the form of the

palmette, even if

derived,

as is not unlikely, from the Egyptian lotus-motive,

was assimilated to the

more

familiar palm-forms of Assyria

(Fig. 20).

FIG.

20.--ASSYRIAN ORNAMENT.

Assyrian

architecture never rivalled the

Egyptian in grandeur or constructive

power,

in

seriousness, or the higher artistic

qualities. It did, however, produce

imposing

results

with the poorest resources, and in its

use of the arch and its

development of

ornamental

forms it furnished prototypes for

some of the most characteristic

features

of

later Asiatic art, which profoundly

influenced both Greek and

Byzantine

architecture.

MONUMENTS:

The most important Chald�an

and Assyrian monuments of

which there

are

extant remains, have already

been enumerated in the text.

It is therefore unnecessary

to

duplicate the list

here.

4.

This

is denied by some recent

writers, so far as the

Chald�ans are

concerned,

and

is not intended here to apply to

the Accadians and Summerians

of primitive

Chald�a.

5.

See

Fergusson, Palaces

of Nineveh and Persepolis,

for an ingenious but

unsubstantiated

argument for the use of

columns in Assyrian

palaces.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.