|

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS |

| << EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE |

| CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS >> |

CHAPTER

III.

EGYPTIAN

ARCHITECTURE--Continued.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Same as for Chapter

II.

TEMPLES.

The

surpassing glory of the New Empire

was its great temples.

Some of

them

were among the most

stupendous creations of structural art.

To temples rather

than

palaces were the resources and

energies of the kings devoted, and

successive

monarchs

found no more splendid outlet for their

piety and ambition than the

founding

of new temples or the extension and

adornment of those already

existing.

By

the forced labor of thousands of

fellaheen (the system is in

force to this day and is

known

as the corv�e)

architectural piles of vast

extent could be erected within

the

lifetime

of a monarch. As in the tombs the

internal walls bore pictures

for the

contemplation

of the Ka, so in the temples the external

walls, for the glory of the

king

and the delectation of the people, were

covered with colored reliefs

reciting the

monarch's

glorious deeds. Internally the worship

and attributes of the gods

were

represented

in a similar manner, in endless

iteration.

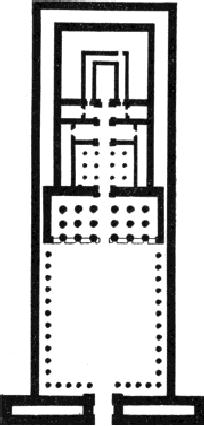

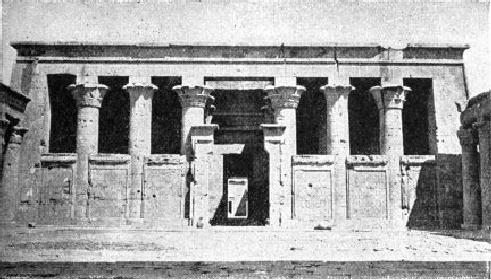

FIG.

9.--TEMPLE OF EDFOU.

PLAN.

THE

TEMPLE SCHEME. This

is admirably shown in the temple of

Khonsu, at

Karnak,

built by Rameses III. (XXth dynasty), and in the

temple of Edfou (Figs. 9

and

10),

though this belongs to the Roman period.

It comprised a sanctuary or sekos,

a

hypostyle (columnar) hall, known as the "hall of

assembly," and a forecourt

preceded

by a double pylon or gateway. Each of

these parts might be made

more or

less

complex in different temples, but the

essential features are

encountered

everywhere

under all changes of form. The building of a

temple began with the

sanctuary,

which contained the sacred chamber and

the shrine of the god, with

subordinate

rooms for the priests and for various

rites and functions.

These

chambers

were low, dark, mysterious,

accessible only to the priests and king.

They

were

given a certain dignity by

being raised upon a sort of

platform above the

general

level,

and reached by a few steps. They were

sumptuously decorated internally

with

ritual

pictures in relief. The hall was

sometimes loftier, but set on a

slightly lower

level;

its massive columns

supported a roof of stone

lintels, and light was

admitted

either

through clearstory windows under the roof of a

central portion higher than

the

sides,

as at Karnak, or over a low screen-wall

built between the columns of the

front

row,

as at Edfou and Denderah. This

method was peculiar to the

Ptolemaic and

Roman

periods. The court was usually

surrounded by a single or double

colonnade;

sometimes,

however, this colonnade only flanked the

sides or fronted the hall, or

again

was wholly wanting. The pylons

were

twin buttress-like masses flanking

the

entrance

gate of the court. They were

shaped like oblong truncated

pyramids,

crowned

by flaring cornices, and were

decorated on the outer face with

masts

carrying

banners, with obelisks, or with seated

colossal figures of the royal

builder.

An

avenue of sphinxes formed the

approach to the entrance, and the whole

temple

precinct

was surrounded by a wall, usually of

crude brick, pierced by one

or more

gates

with or without pylons. The piety of

successive monarchs was

displayed in the

addition

of new hypostyle halls, courts,

pylons, or obelisks, by which the temple

was

successively

extended in length, and sometimes

also in width, by the increased

dimensions

of the new courts. The great Temple of

Karnak most strikingly

illustrates

this

growth. Begun by Osourtesen (XIIth

dynasty) more than 2000 years

B.C., it was

not

completed in its present form until the

time of the Ptolemies, when the last of

the

pylons

and external gates were

erected.

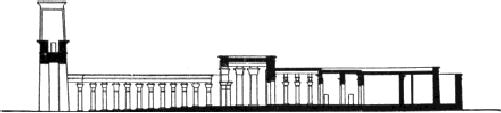

FIG.

10.--TEMPLE OF EDFOU.

SECTION.

The

variations in the details of this general

type were numerous. Thus, at El Kab,

the

temple

of Amenophis III. has the sekos and hall

but no forecourt. At

Deir-el-Medineh

the

hall of the Ptolemaic Hathor-temple is a

mere porch in two parts, while

the

enclosure

within the circuit wall takes the place

of the forecourt. At Karnak all

the

parts

were repeated several times,

and under Amenophis III. (XVIIIth

dynasty)

a

wing was built at a nearly right angle to

the main structure. At Luxor, to a

complete

typical temple were added

three aisles of an unfinished

hypostyle hall, and

an

elaborate forecourt, whose

axis is inclined to that of the other

buildings, owing to

a

bend of the river at that point. At

Abydos a complex sanctuary of many

chambers

extends

southeast at right angles to the general

mass, and the first court is

without

columns.

But in all these structures a certain

unity of effect is produced by the

lofty

pylons,

the flat roofs diminishing in height

over successive portions from the front

to

the

sanctuary, the sloping windowless

walls covered with carved and

painted

pictures,

and the dim and massive interiors of the

columnar halls.

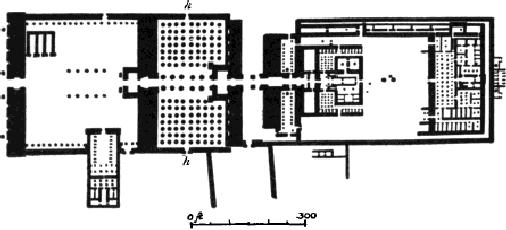

FIG.

11.--TEMPLE OF KARNAK.

PLAN.

TEMPLES

OF KARNAK. Of

these various temples that of

Amen-Ra

is

incomparably

the

largest and most imposing. Its

construction extended through the whole

duration

of

the New Empire, of whose architecture it

is a splendid r�sum�

(Fig.

11). Its

extreme

length is 1,215 feet, and its

greatest width 376 feet. The sanctuary

and its

accessories,

mainly built by Thothmes I. and Thothmes III.,

cover an area nearly

456

�

290 feet in extent, and comprise two

hypostyle halls and countless

smaller halls

and

chambers. It is preceded by a narrow

columnar vestibule and two

pylons

enclosing

a columnar atrium and two obelisks. This

is entered from the Great

Hypostyle

Hall (h

in

Fig. 11; Fig. 12), the noblest

single work of Egyptian

architecture,

measuring 340 � 170 feet, and containing

134 columns in sixteen

rows,

supporting a massive stone

roof. The central columns with

bell-capitals are 70

feet

high and nearly 12 feet in

diameter; the others are

smaller and lower, with lotus-

bud

capitals, supporting a roof

lower than that over the three

central aisles.

A

clearstory of stone-grated windows makes

up the difference in height

between

these

two roofs. The interior, thus lighted,

was splendid with painted

reliefs, which

helped

not only to adorn the hall but to give

scale to its massive parts.

The whole

stupendous

creation was the work of three

kings--Rameses I., Seti I., and

Rameses

II.

(XIXth dynasty).

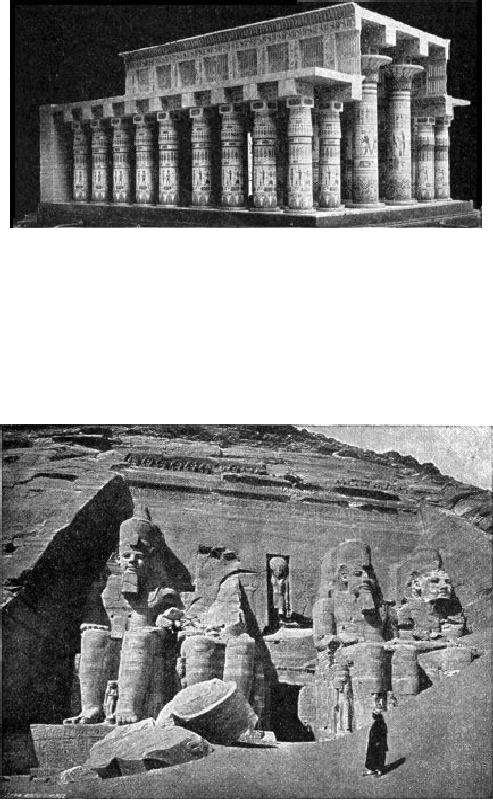

FIG.

12.--CENTRAL PORTION OF HYPOSTYLE

HALL AT KARNAK.

(From

model in Metropolitan Museum, New

York.)

In

front of it was the great court,

flanked by columns, and still

showing the ruins of a

central

avenue of colossal pillars

begun, but never completed, by the

Bubastid kings

of

the XXIId dynasty. One or two smaller

structures and the curious lateral

wing

built

by Amenophis III., interrupt the otherwise

orderly and symmetrical advance

of

this

plan from the sanctuary to the huge first

pylon (last in point of date) erected

by

the

Ptolemies.

FIG.

13.--GREAT TEMPLE OF

IPSAMBOUL.

The

smaller temple of Khonsu,

south of that of Amen-Ra, has

already been alluded

to

as

a typical example of templar

design. Next to Karnak in importance

comes the

Temple

of Luxor in

its immediate neighborhood. It

has two forecourts adorned

with

double-aisled

colonnades and connected by what seems to

be an unfinished hypostyle

hall.

The Ramesseum

and the

temples of Medinet

Abou and

Deir-El-Bahari

have

already

been mentioned. At Gournah and Abydos

are the next most

celebrated

temples

of this period; the first famous for

its rich clustered lotus-columns, the

latter

for

its beautiful sanctuary

chambers, dedicated each to a

different deity, and covered

with

delicate painted reliefs of the

time of Seti I.

GROTTO

TEMPLES. Two

other styles of temple

remain to be noticed. The first

is

the

subterranean or grotto temple, of which

the two most famous, at

Ipsamboul

(Abou-simbel),

were excavated by Rameses II. They

are truly colossal

conceptions,

reproducing

in the native rock the main features of

structural temples, the court

being

represented by the larger of two chambers

in the Greater Temple (Fig.

13)

Their

fa�ades are adorned with

colossal seated figures of the

builder; the smaller

has

also

two effigies of Nefert-Ari, his

consort. Nothing more striking and

boldly

impressive

is to be met with in Egypt than these

singular rock-cut fa�ades.

Other

rock-cut

temples of more modest

dimensions are at Addeh,

Feraig, Beni-Hassan

(the

"Speos

Artemidos"), Beit-el-Wali, and Silsileh.

At Gherf-Hossein, Asseboua, and

Derri

are

temples partly excavated and partly

structural.

PERIPTERAL

TEMPLES. The

last type of temple to be noticed is

represented by only

three

or four structures of moderate size; it

is the peripteral, in which a

small

chamber

is surrounded by columns, usually

mounted on a terrace with vertical

walls.

They

were mere chapels, but are

among the most graceful of

existing ruins. At

Phil�

are

two structures, one by Nectanebo, the

other Ptolemaic, resembling

peripteral

temples,

but without cella-chambers or roofs. They may

have been waiting-courts

for

the

adjoining temples. That at Elephantine

(Amenophis III.) has square

piers at the

sides,

and columns only at the ends. Another by

Thothmes II., at Medinet

Abou,

formed

only a part (the sekos?) of a larger

plan. At Edfou is another, belonging to

the

Ptolemaic

period.

LATER

TEMPLES. After

the architectural inaction of the

Decadence came a

marvellous

recrudescence of splendor under the

Ptolemies, whose Hellenic

origin and

sympathies

did not lead them into the mistaken

effort to impose Greek

models upon

Egyptian

art. The temples erected under their

dominion, and later under Roman

rule,

vied

with the grandest works of the Ramessid�,

and surpassed them in the rich

elaboration

and variety of their architectural

details. The temple at Edfou

(Figs. 9,

10,

14) is the most perfectly preserved, and

conforms most closely to the

typical

plan;

that of Isis, at Phil�, is the most

elaborate and ornate. Denderah

also possesses

a

group of admirably preserved

temples of the same period. At

Esneh, and at

Kalabsh�

and Kardassy or Ghertashi in Nubia

are others. In all these one

notes

innovations

of detail and a striving for effect

quite different from the simpler

majesty

of

the preceding age (Fig. 14). One peculiar

feature is the use of screen

walls built

into

the front rows of columns of the

hypostyle hall. Light was

admitted above these

walls,

which measured about half the height of

the columns and were interrupted

at

the

centre by a curious doorway cut through

their whole height and without any

lintel.

Long disused types of

capital were revived and

others greatly elaborated;

and

the

wall-reliefs were arranged in

bands and panels with a regularity and

symmetry

rather

Greek than Egyptian.

FIG.

14.--EDFOU. FRONT OF HYPOSTYLE

HALL.

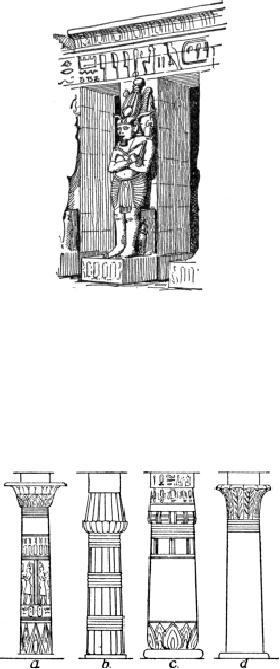

ARCHITECTURAL

DETAILS. With the

exception of a few purely utilitarian

vaulted

structures,

all Egyptian architecture was

based on the principle of the lintel.

Artistic

splendor

depended upon the use of painted and

carved pictures, and the

decorative

treatment

of the very simple supports employed.

Piers and columns sustained

the

roofs

of such chambers as were too

wide for single lintels, and

produced, in halls

like

those

of Karnak, of the Ramesseum, or of

Denderah, a stupendous effect by

their

height,

massiveness, number, and colored

decoration. The simplest piers

were plain

square

shafts; others, more

elaborate, had lotus stalks and

flowers or heads of

Hathor

carved upon them. The most striking

were those against whose

front faces

were

carved colossal figures of

Osiris, as at Luxor, Medmet Abou, and

Karnak (Fig.

15).

The columns, which were seldom

over six diameters in

height, were treated

with

greater

variety; the shafts, slightly

tapering upward, were either round or

clustered in

section,

and usually contracted at the base. The

capitals with which they were

crowned

were usually of one of the

five chief types described

below. Besides round

and

clustered shafts, the Middle Empire and a

few of the earlier monuments of

the

New

Empire employed polygonal or

slightly fluted shafts, as at Beni

Hassan and

Karnak;

these had a plain square

abacus, with sometimes a cushion-like

echinus

beneath

it. A round plinth served as a base for

most of the columns.

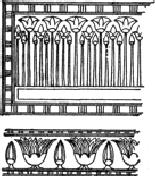

CAPITALS.

The

five chief types of capital

were: a, the

plain lotus bud, as at

Karnak

(Great

Hall); b, the

clustered lotus bud (Beni-Hassan,

Karnak, Luxor, Gournah, etc.);

c, the

campaniform

or

inverted bell (central

aisles at Karnak, Luxor, the

Ramesseum);

d, the

palm-capital, frequent in the later

temples; and e, the

Hathor-headed, in which

heads

of Hathor adorn the four faces of a

cubical mass surmounted by a

model of a

shrine

(Sedinga, Edfou, Denderah,

Esneh). These types were

richly embellished and

varied

by the Ptolemaic architects, who gave a

clustered or quatrefoil plan to the

bell-

capital,

or adorned its surface with palm

leaves. A few other forms

are met with as

exceptions.

The first four are shown in Fig.

16.

FIG.

15.--OSIRID PIER (MEDINET

ABOU).

Every

part of the column was richly decorated in

color. Lotus-leaves or

petals

swathed

the swelling lower part of the shaft,

which was elsewhere covered

with

successive

bands of carved pictures and of

hieroglyphics. The capital was

similarly

covered

with carved and painted ornament,

usually of lotus-flowers or leaves,

or

alternate

stalks of lotus and

papyrus.

FIG.

16.--TYPES OF COLUMN.

a,

Campaniform; b, Clustered

Lotus-Column;

c,

Simple Lotus-Column; d,

Palm-Column.

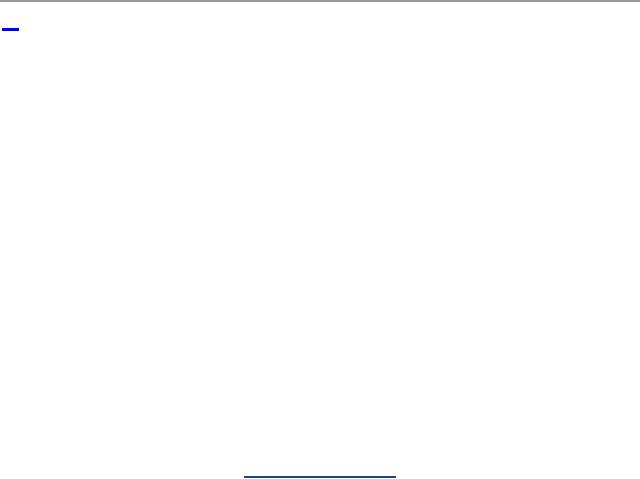

The

lintels were plain and

square in section, and often of

prodigious size. Where

they

appeared

externally they were crowned with a

simple cavetto cornice, its

curved

surface

covered with colored flutings

alternating with cartouches

of

hieroglyphics.

Sometimes,

especially on the screen walls of the

Ptolemaic age, this was

surmounted

by

a cresting of adders or ur�i in

closely serried rank. No other form of

cornice or

cresting

is met with. Mouldings as a means of

architectural effect were

singularly

lacking

in Egyptian architecture. The only

moulding known is the clustered

torus

(torus

= a

convex moulding of semicircular

profile), which resembles a bundle

of

reeds

tied together with cords or

ribbons. It forms an astragal under the

cavetto

cornice

and runs down the angles of the pylons and

walls.

FIG.

17.--EGYPTIAN FLORAL

ORNAMENT-FORMS.

POLYCHROMY

AND ORNAMENT. Color

was absolutely essential to the

decorative

scheme.

In the vast and dim interiors, as well as in the

blinding glare of the sun,

mere

sculpture or relief would have

been wasted. The application of

brilliant color to

pictorial

forms cut in low relief, or outlined by

deep incision with the edges of

the

figures

delicately rounded (intaglio

rilievo)

was the most appropriate

treatment

possible.

The walls and columns were

covered with pictures treated in this

way, and

the

ceilings and lintels were

embellished with symbolic forms in the

same manner.

All

the ornaments, as distinguished from the

paintings, were symbolical, at

least in

their

origin. Over the gateway was the

solar disk or globe with

wide-spread wings,

the

symbol of the sun winging its way to the

conquest of night; upon the ceiling

were

sacred

vultures, zodiacs, or stars

spangled on a blue ground.

Externally the temples

presented

only masses of unbroken wall; but these,

as well as the pylons, were

covered

with huge pictures of a historical

character. Only in the tombs do we

find

painted

ornament of a purely conventional sort

(Fig. 17). Rosettes, diaper

patterns,

spirals,

and checkers are to be met with in them; but many of

these can be traced

to

symbolic

origins.3

DOMESTIC

ARCHITECTURE. The only

remains of palaces are the

pavilion of

Rameses

III. at Medinet Abou, and another at

Semneh. The Royal Labyrinth

has so

completely

perished that even its site

is uncertain. The Egyptians lived so much

out

of

doors that the house was a

less important edifice than in

colder climates.

Egyptian

dwellings

were probably in most cases

built of wood or crude brick, and

their

disappearance

is thus easily explained. Relief

pictures on the monuments indicate

the

use

of wooden framing for the walls, which

were probably filled in with

crude brick

or

panels of wood. The architecture

was extremely simple.

Gateways like those of

the

temples

on a smaller scale, the cavetto

cornice on the walls, and here and

there a

porch

with carved columns of wood or

stone, were the only details

pretending to

elegance.

The ground-plans of many houses in ruined

cities, as at Tel-el-Amarna and

a

nameless city of Amenophis IV., are

discernible in the ruins; but the

superstructures

are wholly wanting. It was in

religious and sepulchral

architecture

that

the constructive and artistic genius of

the Egyptians was most fully

manifested.

MONUMENTS:

The principal necropolis

regions of Egypt are centred

about Ghizeh and

ancient

Memphis for the Old Empire

(pyramids and mastabas),

Thebes for the

Middle

Empire

(Silsileh, Beni Hassan), and

Thebes (Vale of the Kings,

Vale of the Queens)

and

Abydos

for the New Empire.

The

Old Empire has also left us

the Sphinx, Sphinx temple,

and the temple at

Meidoum.

The

most important temples of

the New Empire were those of

Karnak (the great

temple,

the

southern or temple of Khonsu), of

Luxor, Medinet Abou (great

temple of Rameses III.,

lesser

temples of Thothmes II. and III. with

peripteral sekos; also

Pavilion of Rameses

III.);

of Abydos; of Gournah; of Eilithyia

(Amenophis III.); of Soleb

and Sesebi in Nubia;

of

Elephantine (peripteral); the

tomb temple of Deir-el-Bahari,

the Ramesseum, the

Amenopheum;

hemispeos at Gherf Hossein; two

grotto temples at

Ipsamboul.

At

Mero� are pyramids of the

Ethiopic kings of the

Decadence.

Temples

of the Ptolemaic period:

Phil�, Denderah.

Temples

of the Roman period: Koum

Ombos, Edfou; Kalabsh�,

Kardassy and Dandour

in

Nubia;

Esneh.

3.

See

Goodyear's Grammar

of the Lotus for

an elaborate and

ingenious

presentation

of the theory of a common

lotus-origin for all the

conventional forms

occurring

in Egyptian ornament.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.