|

ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE |

| << ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS |

| APPENDIX. >> |

CHAPTER

XXVIII.

ORIENTAL

ARCHITECTURE.

INDIA,

CHINA, AND JAPAN.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Cole,

Monographs

of Ancient Monuments of

India.

Conder,

Notes

on Japanese Architecture (in

Transactions of R.I.B.A., for 1886).

Cunningham,

Arch�ological

Survey of India.

Fergusson, Indian

and Eastern Architecture;

Picturesque

Illustrations

of Indian Architecture. Le

Bon, Les

Monuments de l'Inde.

Morse, Japanese

Houses.

Stirling, Asiatic

Researches.

Consult also the Journal

and

the Transactions

of

the

Royal Asiatic

Society.

INTRODUCTORY

NOTE. The

architecture of the non-Moslem countries

and races of

Asia

has been reserved for this

closing chapter, in order not to

interrupt the

continuity

of the history of European styles, with

which it has no affinity and

scarcely

even a point of contact. Among them all,

India alone has

produced

monuments

of great architectural importance. The

buildings of China and

Japan,

although

interesting for their style, methods, and

detail, and so deserving at least

of

brief

mention, are for the most part of

moderate size and of perishable

materials.

Outside

of these three countries

there is little to interest the general

student of

architecture.

INDIA:

PERIODS. It is

difficult to classify the non-Mohammedan

styles of India,

owing

to their frequently overlapping, both

geographically and artistically; while

the

lack

of precise dates in Indian literature

makes the chronology of many of

the

monuments

more or less doubtful. The divisions

given below are a

modification of

those

first established by Fergusson, and

are primarily based on the

three great

religions,

with geographical subdivisions, as

follows:

THE

BUDDHIST STYLE, from the reign of Asoka,

cir.

250

B.C., to the 7th century

A.D.

Its monuments occupy mainly a broad

band running northeast and

southwest,

between

the Indian Desert and the Dekkan.

Offshoots of the style are found as

far

north

as Gandhara, and as far south as

Ceylon.

THE

JAINA STYLE, akin to the

preceding if not derived from it,

covering the same

territory

as well as southern India; from 1000 A.D. to the

present time.

THE

BRAHMAN or HINDU STYLES, extending over

the whole peninsula. They are

sub-divided

geographically into the NORTHERN BRAHMAN, the

CHALUKYAN in the

Dekkan,

and the DRAVIDIAN in the south; this last

style being coterminous with

the

populations

speaking the Tamil and cognate languages.

The monuments of these

styles

are mainly subsequent to the 10th century, though a

few date as far back as

the

7th.

The

great majority of Indian monuments

are religious--temples, shrines,

and

monasteries.

Secular buildings do not appear until

after the Moslem conquests,

and

most

of them are quite

modern.

GENERAL

CHARACTER. All

these styles possess certain

traits in common.

While

stone

and brick are both used,

sandstone predominating, the details

are in large

measure

derived from wooden prototypes.

Structural lines are not

followed in the

exterior

treatment, purely decorative

considerations prevailing. Ornament is

equally

lavished

on all parts of the building, and is

bewildering in its amount and

complexity.

Realistic and grotesque sculpture is

freely used, forming

multiplied

horizontal

bands of extraordinary richness and

minuteness of execution.

Spacious

and

lofty interiors are rarely

attempted, but wonderful effects are

produced by

seemingly

endless repetition of columns in

halls, and corridors, and by

external

emphasis

of important parts of the plan by lofty

tower-like piles of

masonry.

The

source of the various Indian styles, the

origin of the forms used, the

history of

their

development, are all wrapped in

obscurity. All the monuments show a

fully

developed

style and great command of

technical resources from the outset.

When,

where,

and how these were attained is as yet an

unsolved mystery. In all its

phases

previous

to the Moslem conquest Indian

architecture appears like an

indigenous art,

borrowing

little from foreign styles, and having no

affinities with the arts of

Occidental

nations.

BUDDHIST

STYLE. Although

Buddhism originated in the sixth century

B.C., the

earliest

architectural remains of the style

date from its wide

promulgation in India

under

Asoka (272236 B.C.). Buddhist

monuments comprise three

chief classes of

structures:

the stupas

or

topes, which

are mounds more or less

domical in shape,

enclosing

relic-shrines of Buddha, or built to mark

some sacred spot; chaityas,

or

temple

halls, cut in the rock; and viharas, or

monasteries. The style of the

detail

varies

considerably in these three

classes, but is in general simpler and

more massive

than

in the other styles of India.

TOPES.

These

are found in groups, of which the most

important are at or near

Bhilsa

in

central India, at Manikyala in the

northwest, at Amravati in the south, and

in

Ceylon

at Ruanwalli and Tuparamaya. The best

known among them is the Sanchi

Tope,

near Bhilsa, 120 feet in

diameter and 56 feet high. It is

surrounded by a richly

carved

stone rail or fence, with

gateways of elaborate workmanship,

having three

sculptured

lintels crossing the carved

uprights. The tope at Manikyala is

larger, and

dates

from the 7th century. It is exceeded in size by many

in Ceylon, that at

Abayagiri

measuring 360 feet in diameter.

Few of the topes retain the

tee, or

model

of

a shrine, which, like a lantern,

once crowned each of

them.

Besides

the topes there are a few

stupas of tower-like form, square in

plan, of which

the

most famous is that at Buddh

Gaya,

near the sacred Bodhi tree,

where Buddha

attained

divine light in 588 B.C.

CHAITYA

HALLS. The

Buddhist speos-temples--so far as known the only

extant

halls

of worship of that religion, except

one at Sanchi--are mostly in the

Bombay

Presidency,

at Ellora, Karli, Ajunta, Nassick, and

Bhaja. The earliest, that at

Karli,

dates

from 78 B.C., the latest (at

Ellora), cir.

600 A.D. They

consist uniformly of a

broad

nave ending in an apse, and

covered by a roof like a

barrel vault, and two

narrow

side aisles. In the apse is the

dagoba

or

relic-shrine, shaped like a

miniature

tope.

The front of the cave was originally

adorned with an open-work screen or

frame

of

wood, while the face of the rock

about the opening was carved

into the semblance

of

a sumptuous structural fa�ade.

Among the finest of these

caverns is that at Karli,

whose

massive columns and impressive

scale recall Egyptian

models, though the

resemblance

is superficial and has no historic

significance. More suggestive is

the

affinity

of many of the columns which stand before

these caves to Persian

prototypes

(see

Fig.

21).

It is not improbable that both Persian and

classic forms were

introduced

into India through the Bactrian kingdom 250

years B.C. Otherwise

we

must

seek for the origin of nearly all

Buddhist forms in a pre-existing

wooden

architecture,

now wholly perished, though its

traditions may survive in the

wooden

screens

in the fronts of the caves. While

some of these caverns are

extremely simple,

as

at Bhaja, others, especially at

Nassick

and

Ajunta,

are of great splendor

and

complexity.

VIHARAS.

Except

at Gandhara in the Punjab, the structural

monasteries of the

Buddhists

were probably all of wood and

have long ago perished. The

Gandhara

monasteries

of Jamalgiri and Takht-i-Bahi present in

plan three or four courts

surrounded

by cells. The centre of one court is in

both cases occupied by a

platform

for

an altar or shrine. Among the ruins

there have been found a number of

capitals

whose

strong resemblance to the Corinthian type

is now generally attributed to

Byzantine

rather than Bactrian influences.

These viharas may therefore be

assigned to

the

6th or 7th century A.D.

The

rock-cut viharas are found in the

neighborhood of the chaityas already

described.

Architecturally,

they are far more elaborate than the

chaityas. Those at

Salsette,

Ajunta,

and Bagh are particularly

interesting, with pillared halls or

courts, cells,

corridors,

and shrines. The hall of the Great

Vihara at

Bagh

is 96

feet square, with

36

columns. Adjoining it is the school-room,

and the whole is fronted by a

sumptuous

rock-cut colonnade 200 feet

long. These caves were

mostly hewn

between

the 5th and 7th centuries, at which time

sculpture was more prevalent

in

Buddhist

works than previously, and some of them

are richly adorned with

figures.

JAINA

STYLE. The

religion and the architecture of the

Jainas so closely

resemble

those

of the Buddhists, that recent authorities

are disposed to treat the

Jaina style as

a

mere variation or continuation of the

Buddhist. Chronologically they are

separated

by

an interval of some three

centuries, cir.

650950

A.D., which have left us almost

no

monuments of either style. The

Jaina is moreover easily

distinguished from the

Buddhist

architecture by the great number and

elaborateness of its

structural

monuments.

The multiplication of statues of Tirthankhar in the

cells about the

temple

courts, the exuberance of sculpture, the

use of domes built in

horizontal

courses,

and the imitation in stone of wooden

braces or struts are among

its

distinguishing

features.

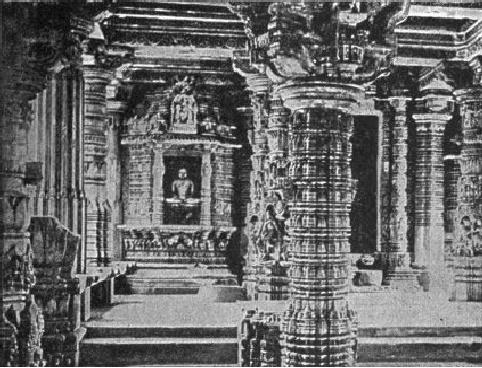

FIG.

226.--PORCH OF TEMPLE ON MOUNT

ABU.

JAINA

TEMPLES. The

earliest examples are on

Mount

Abu in the Indian

Desert.

Built

by Vimalah Sah in 1032, the chief of

these consists of a court measuring

140

�

90 feet, surrounded by cells and a

double colonnade. In the centre

rises the shrine

of

the god, containing his

statue, and terminating in a lofty tower

or sikhra.

An

imposing

columnar porch, cruciform in plan,

precedes this cell (Fig. 226).

The

intersection

of the arms is covered by a dome

supported on eight columns with

stone

brackets

or struts. The dome and columns

are covered with profuse

carving and

sculptured

figures, and the total effect is

one of remarkable dignity and

splendor. The

temple

of Sadri

is much

more extensive, twenty minor domes and

one of larger size

forming

cruciform porches on all four sides of

the central sikhra. The

cells about the

court

are each covered by a small

sikhra, and

these, with the twenty-one domes

(four

of

which are built in three stories), all

grouped about the central

tower and adorned

with

an astonishing variety of detail,

constitute a monument of the first

importance.

It

was built by Khumbo Rana, about 1450. At

Girnar

are

several 12th-century

temples

with enclosed instead of open

vestibules. One of these, that of

Neminatha,

retains

intact its court enclosure and

cells, which in most other

cases have perished.

The

temple at Somnath

resembles

it, but is larger; the dome of its

porch, 33 feet in

diameter,

is the largest Jaina dome in India. Other

notable temples are at

Gwalior,

Khajuraho,

and Parasnatha.

In

all the Jaina temples the salient

feature is the sikhra or vimana.

This is a tower of

approximately

square plan, tapering by a graceful

curve toward a peculiar

terminal

ornament

shaped like a flattened

melon. Its whole surface is variegated by

horizontal

bands

and vertical breaks, covered with

sculpture and carving. Next in

importance

are

the domes, built wholly in horizontal

courses and resting on stone

lintels carried

by

bracketed columns. These

same traits appear in

relatively modern examples, as

at

Delhi.

FIG.

227.--TOWER OF VICTORY,

CHITTORE.

TOWERS.

A

similar predilection for minutely broken

surfaces marks the

towers

which

sometimes adjoin the temples, as at

Chittore (tower of Sri

Allat,

13th

century),

or were erected as trophies of victory,

like that of Khumbo

Rana in

the

same

town (Fig. 227). The combination of

horizontal and vertical lines,

the

distribution

of the openings, and the rich ornamentation of

these towers are very

interesting,

though lacking somewhat in structural

propriety of design.

HINDU

STYLES: NORTHERN BRAHMAN.

The

origin of this style is as yet an

unsolved

problem. Its monuments were mainly built

between 600 and 1200 A.D.,

the

oldest being in Orissa, at

Bhuwanesevar, Kanaruk, and Puri. In

northern India

the

temples are about equally

divided between the two forms of

Brahmanism--the

worship

of Vishnu or Vaishnavism, and that of

Siva or Shaivism--and do not

differ

materially

in style. As in the Jaina style, the

vimana

is their

most striking

feature,

and

this is in most cases adorned with

numerous reduced copies of

its own form

grouped

in successive stages against

its sides and angles. This

curious system of

design

appears in nearly all the great

temples, both of Vishnu and Siva. The

Jaina

melon

ornament is universal, surmounted

generally by an urn-shaped

finial.

In

plan the vimana shrine is preceded by two

or three chambers, square or

polygonal,

some

with and some without columns. The

foremost of these is covered by a

roof

formed

like a stepped pyramid set

cornerwise. The fine porch of the

ruined temple at

Bindrabun

is

cruciform in plan and forms the chief

part of the building, the shrine

at

the

further end being relatively

small and its tower

unfinished or ruined. In

some

modern

examples the antechamber is replaced by

an open porch with a

Saracenic

dome,

as at Benares; in others the old type is

completely abandoned, as in the

temple

at

Kantonnuggur

(170422).

This is a square hall built of

terra-cotta, with four

three-arched

porches and nine towers,

more Saracenic than Brahman in

general

aspect.

The

Kandarya

Mahadeo, at

Khajuraho, is the most noted

example of the northern

Brahman

style, and one of the most

splendid structures extant. A

strong and lofty

basement

supports an extraordinary mass of

roofs, covering the six open

porches and

the

antechamber and hypostyle hall, which

precede the shrine, and rising

in

successive

pyramidal masses until the vimana is

reached which covers the

shrine.

This

is 116 feet high, but seems much

loftier, by reason of the small

scale of its

constituent

parts and the marvellously minute

decoration which covers the whole

structure.

The vigor of its masses and the

grand stairways which lead up to it

give it

a

dignity unusual for its size, 60 � 109

feet in plan (cir.

1000

A.D.).

At

Puri, in Orissa, the Temple

of

Jugganat, with

its double enclosure and

numerous

subordinate

shrines, the Teli-ka-Mandir at Gwalior, and

temples at Udaipur

near

Bhilsa,

at Mukteswara

in

Orissa, at Chittore, Benares, and

Barolli, are

important

examples.

The few tombs erected subsequent to the

Moslem conquest,

combining

Jaina

bracket columns with Saracenic

domes, and picturesquely situated

palaces at

Chittore

(1450), Oudeypore (1580), and Gwalior, should

also be mentioned.

CHALUKYAN

STYLE. Throughout

a central zone crossing the

peninsula from sea to

sea

about the Dekkan, and extending

south to Mysore on the west, the

Brahmans

developed

a distinct style during the

later centuries of the Chalukyan dynasty.

Its

monuments

are mainly comprised between 1050 and the

Mohammedan conquest in

1310.

The most notable examples of the

style are found along the

southwest coast,

at

Hullabid, Baillur, and

Somnathpur.

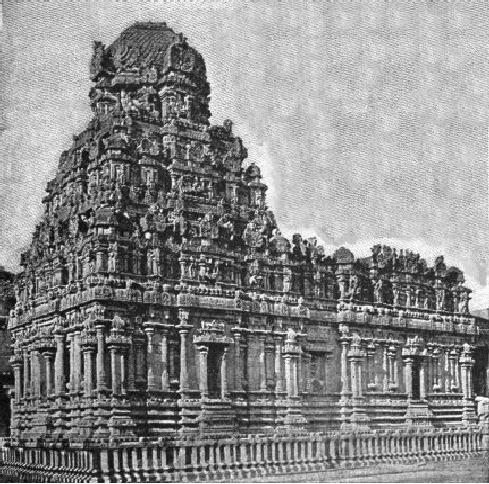

FIG.

228.--TEMPLE AT HULLAB�D.

DETAIL.

TEMPLES.

Chalukyan

architecture is exclusively religious and

its temples are

easily

recognized.

The plans comprise the same

elements as those of the Jainas, but

the

Chalukyan

shrine is always star-shaped

externally in plan, and the vimana takes

the

form

of a stepped pyramid instead of a

curved outline. The Jaina

dome is, moreover,

wholly

wanting. All the details are of

extraordinary richness and beauty, and

the

breaking

up of the surfaces by rectangular

projections is skilfully managed so as

to

produce

an effect of great apparent

size with very moderate dimensions. All

the

known

examples stand on raised

platforms, adding materially to their

dignity. Some

are

double temples, as at Hullabid

(Fig. 228); others are

triple in plan. A noticeable

feature

of the style is the deeply cut

stratification of the lower part of the

temples,

each

band or stratum bearing a

distinct frieze of animals,

figures or ornament,

carved

with

masterly skill. Pierced

stone slabs filling the window

openings are also not

uncommon.

The

richest exemplars of the style

are the temples at Baillur

and

Somnathpur, and at

Hullab�d

the Kait

Iswara and the

incomplete Double

Temple. The Kurti

Stambha, or

gate

at Worangul, and the Great Temple at

Hamoncondah

should

also be mentioned.

DRAVIDIAN

STYLE. The

Brahman monuments of southern India

exhibit a style

almost

as strongly marked as the Chalukyan.

This appears less in their

details than in

their

general plan and conception. The

Dravidian temples are not

single structures,

but

aggregations of buildings of varied

size and form, covering extensive

areas

enclosed

by walls and entered through gates

made imposing by lofty pylons

called

gopuras. As if to

emphasize these superficial

resemblances to Egyptian models,

the

sanctuary

is often low and insignificant. It is

preceded by much more

imposing

porches

(mantapas) and

hypostyle halls or choultries, the

latter being sometimes

of

extraordinary

extent, though seldom lofty. The

choultrie, sometimes called the Hall

of

1,000

Columns, is in some cases

replaced by pillared corridors of

great length and

splendor,

as at Ramisseram

and

Madura.

The

plans are in most cases

wholly

irregular,

and the architecture, so far from resembling the

Egyptian in its scale

and

massiveness,

is marked by the utmost minuteness of

ornament and tenuity of detail,

suggesting

wood and stucco rather than

stone. The Great

Hall at

Chillambaram is

but

10 to 12 feet high, and the corridors at

Ramisseram, 700 feet long,

are but 30

feet

high. The effect of ensemble

of the

Dravidian temples is disappointing. They

lack

the

emphasis of dominant masses and the

dignity of symmetrical and

logical

arrangement.

The very loftiness of the gopuras makes

the buildings of the group

within

seem low by contrast. In nearly

every temple, however, some

one feature

attracts

merited admiration by its

splendor, extent, or beauty.

Such are the

Choultrie, built by

Tirumalla Nayak at Madura (162345),

measuring 333 � 105

feet;

the corridors already mentioned at

Ramisseram and in the Great

Temple at

Madura;

the gopuras at Tarputry

and

Vellore, and the Mantapa

of

Parvati

at

Chillambaram

(15951685). Very noticeable are the

compound columns of this

style,

consisting of square piers with

slender shafts coupled to them and

supporting

brackets,

as at Chillambaram, Peroor, and Vellore;

the richly banded square

piers,

the

grotesques of rampant horses and

monsters, and the endless labor

bestowed upon

minute

carving and ornament in superposed

bands.

OTHER

MONUMENTS. Other

important temples are at Tiruvalur,

Seringham,

Tinevelly,

and Conjeveram, all alike in general

scheme of design, with

enclosures

varying

from 300 to 1,000 feet in length and width. At

Tanjore

is a

magnificent

temple

with two courts, in the larger of which

stands a pagoda

or

shrine with a

pyramidal

vimana, unusual in Dravidian temples, and

beside it the smaller Shrine

of

Soubramanya

(Fig.

229), a structure of unusual beauty of

detail. In both, the vertical

lower

story with its pilasters and

windows is curiously suggestive of

Renaissance

design.

The pagoda dates from the 14th, the

smaller temple from the 15th

century.

ROCK-CUT

RATHS. All the

above temples were built

subsequently to the 12th

century.

The rock-cut shrines date in

some cases as far back as the 7th

century; they

are

called kylas

and

raths, and

are not caves, but isolated

edifices, imitating

structural

designs, but hewn bodily from the rock.

Those at Mahavellipore are

of

diminutive

size; but at Purudkul

there

is an extensive temple with shrine,

choultrie,

and

gopura surrounded by a court enclosure

measuring 250 � 150 feet (9th

century).

More famous still is the elaborate

Kylas

at

Ellora, of

about the same size

as

the

above, but more complex and

complete in its

details.

PALACES.

At Madura,

Tanjore, and Vijayanagar are

Dravidian palaces, built

after

the

Mohammedan conquest and in a mixed

style. The domical octagonal

throne-room

and

the Great

Hall at Madura

(17th century), the most famous

edifices of the kind,

were

evidently inspired from Gothic

models, but how this came about is not

known.

The

Great Hall with its pointed

arched barrel vault of 67 feet

span, its cusped

arches,

round piers, vaulting shafts, and

triforium, appears strangely foreign to

its

surroundings.

FIG.

229.--SHRINE OF SOUBRAMANYA,

TANJORE.

CAMBODIA.

The

subject of Indian architecture cannot be

dismissed without at least

brief

mention of the immense temple of

Nakhon

Wat in

Cambodia. This

stupendous

creation

covers an area of a full square

mile, with its concentric

courts, its

encircling

moat

or lake, its causeways,

porches, and shrines, dominated by a

central structure

200

feet square with nine pagoda-like

towers. The corridors around the inner

court

have

square piers of almost

classic Roman type. The rich

carving, the perfect

masonry,

and the admirable composition of the whole

leading up to the central

mass,

indicate

architectural ability of a high

order.

CHINESE

ARCHITECTURE. No purely

Mongolian nation appears

ever to have

erected

buildings of first-rate importance. It

cannot be denied, however, that

the

Chinese

are possessed of considerable

decorative skill and mechanical

ingenuity; and

these

qualities are the most

prominent elements in their buildings.

Great size and

splendor,

massiveness and originality of

construction, they do not possess. Built

in

large

measure of wood, cleverly

framed and decorated with a certain

richness of color

and

ornament, with a large element of the

grotesque in the decoration, the

Chinese

temples,

pagodas, and palaces are

interesting rather than impressive.

There is not a

single

architectural monument of imposing size

or of great antiquity, so far as we

know.

The celebrated Porcelain

Tower of Nankin is

no longer extant, having

been

destroyed

in the T�ping rebellion in 1850. It was a

nine-storied polygonal

pagoda

236

feet high, revetted with

porcelain tiles, and was built in 1412.

The largest of

Chinese

temples, that of the Great

Dragon at

Pekin, is a circular structure

of

moderate

size, though its enclosure is

nearly a mile square.

Pagodas with diminishing

stories,

elaborately carved entrance

gates and successive terraces

are mainly relied

upon

for effect. They show little structural art, but much

clever ornament. Like

the

monasteries

and the vast lamaseries

of

Thibet, they belong to the Buddhist

religion.

Aside

from the ingenious framing and bracketing

of the carpentry, the most

striking

peculiarity

of Chinese buildings is their

broad-spreading tiled roofs.

These invariably

slope

downward in a curve, and the tiling, with

its hip-ridges, crestings, and

finials

in

terra-cotta or metal, adds

materially to the picturesqueness of the

general effect.

Color

and gilding are freely used,

and in some cases--as in a summer

pavilion at

Pekin--porcelain

tiling covers the walls, with

brilliant effect. The chief

wonder is that

this

resource of the architectural decorator

has not been further developed in

China,

where

porcelain and earthenware are

otherwise treated with such

remarkable skill.

JAPANESE

ARCHITECTURE. Apparently

associated in race with the Chinese

and

Koreans,

the Japanese are far more

artistic in temperament than either of

their

neighbors.

The refinement and originality of their

decorative art have given it a

wide

reputation.

Unfortunately the prevalence of earthquakes

has combined with the

influence

of the traditional habits of the people

to prevent the maturing of a truly

monumental

architecture. Except for the terraces,

gates, and enclosures of their

palaces

and temples, wood is the predominant

building material. It is

used

substantially

as in China, the framing, dovetailing,

bracketing, broad eaves and

tiled

roofs

of Japan closely resembling

those of China. The chief

difference is in the greater

refinement

and delicacy of the Japanese details and

the more monumental

disposition

of

the temple terraces, the beauty of which

is greatly enhanced by skillful

landscape

gardening.

The gateways recall somewhat

those of the Sanchi Tope in India, but

are

commonly

of wood. Owing to the danger from

earthquakes, lofty towers and

pagodas

are

rarely seen.

The

domestic architecture of Japan, though

interesting for its arrangements, and

for

its

sensible and artistic use of the

most flimsy materials, is too

trivial in scale,

detail,

and

construction to receive more than

passing reference. Even the

great palace at

buildings

of wood, with little of splendor or

architectural dignity.

MONUMENTS

(additional

to those in text). BUDDHIST: Topes at

Sanchi, Sonari,

Satdara,

Andher, in Central India; at

Sarnath, near Benares; at

Jelalabad and Salsette;

in

Ceylon

at Anuradhapura, Tuparamaya,

Lankaramaya.--Grotto temples (chaityas),

mainly

in

Bombay and Bengal

Presidencies; at Behar, especially

the Lomash Rishi, and

Cuttack;

at

Bhaja, Bedsa, Ajunta, and

Ellora (Wiswakarma Cave); in

Salsette, the Kenheri

Cave.--

Viharas:

Structural at Nalanda and

Sarnath, demolished; rock-cut in

Bengal, at Cuttack,

Udayagiri

(the Ganesa); in the west,

many at Ajunta, also at

Bagh, Bedsa, Bhaja,

Nassick

(the

Nahapana, Vadnya Sri, etc.),

Salsette, Ellora (the

Dekrivaria, etc.). In Nep�l,

stupas

of

Swayanbunath and

Bouddhama.

JAINA:

Temples at Aiwulli, Kanaruc

(Black Pagoda), and

Purudkul; groups of temples

at

Palitana,

Gimar, Mount Abu, Somnath,

Parisnath; the Sas Bahu at

Gwalior, 1093;

Parswanatha

and Ganthai (650) at

Khajuraho; temple at Gyraspore, 7th

century; modern

temples

at Ahmedabad (Huttising), Delhi,

and Sonaghur; in the south

at Moodbidri,

Sravana

Belgula; towers at

Chittore.

NORTHERN

BRAHMAN: Temples, Parasumareswara (500

A.D.), Mukteswara, and

Great

Temple

(600650), all at Bhuwaneswar,

among many others; of

Papanatha at Purudkul;

grotto

temples at Dhumnar, Ellora,

and Poonah; temples at

Chandravati, Udaipur,

and

Amritsur

(the last modern); tombs of

Singram Sing and others at

Oudeypore; of Rajah

Baktawar

at Ulwar, and others at Goverdhun;

gh�ts or landings at Benares

and elsewhere.

CHALUKYAN:

Temples at Buchropully and

Hamoncondah, 1163; ruins at

Kalyani;

grottoes

of Hazar Khutri.

DRAVIDIAN:

Rock-cut temples (raths) at

Mahavellipore; Tiger Cave at

Saluvan Kuppan;

temples

at Pittadkul (Purudkul), Tiruvalur,

Combaconum, Vellore, Peroor,

Vijayanagar;

pavilions

at Tanjore and

Vijayanagar.

There

are also many temples in

the Kashmir Valley difficult

of assignment to any of

the

above

styles and religions.

28.

See

Transactions R.I.B.A., 52d year, 1886,

article by R. J. Conder, pp.

185

214.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.