|

ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS |

| << RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE |

| ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE >> |

CHAPTER

XXVII.

ARCHITECTURE

IN THE UNITED STATES.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Fergusson,

Statham. Also, Chandler,

The

Colonial

Architecture

of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and

Virginia.

Cleaveland and

Campbell,

American

Landmarks.

Corner and Soderholz,

Colonial

Architecture in New England.

Crane

and Soderholz, Examples

of Colonial Architecture in Charleston

and Savannah.

Drake,

Historic

Fields and Mansions of

Middlesex.

Everett, Historic

Churches of

America.

King, Handbook

of Boston;

Handbook

of New York.

Little, Early

New England

Interiors.

Schuyler, American

Architecture. Van

Rensselaer, H.

H. Richardson and

His

Works.

Wallis, Old

Colonial Architecture and

Furniture.

GENERAL

REMARKS. The

colonial architecture of modern

times presents a

peculiar

phenomenon.

The colonizing nation, carrying into

its new habitat

the

tastes and

practices

of a long-established civilization,

modifies these only with the

utmost

reluctance,

under the absolute compulsion of new

conditions. When the new home is

virgin

soil, destitute of cultivation,

government, or civilized inhabitants,

the

accompaniments

and activities of civilization introduced

by the colonists manifest

themselves

at first in curious contrast to the

primitive surroundings. The

struggle

between

organized life and chaos, the

laborious subjugation of nature to

the

requirements

of our complex modern life, for a

considerable period absorb

the

energies

of the colonists. The amenities of

culture, the higher intellectual

life, the

refinements

of art can, during this period,

receive little attention. Meanwhile a

new

national

character is being formed; the

people are undergoing the

moral training

upon

which their subsequent achievements must

depend. With the conquest of brute

nature,

however, and the gradual emergence of a

more cultivated class, with

the

growth

of commerce and wealth and the consequent

increase of leisure, the

humanities

find more place in the colonial

life. The fine arts appear

in scattered

centres

determined by peculiarly favorable

conditions. For a long time

they retain the

impress,

and seek to reproduce the forms, of the

art of the mother country. But new

conditions

impose a new development. Maturing

commerce with other lands

brings

in

foreign influences, to which the still

unformed colonial art is

peculiarly

susceptible.

Only with political and commercial

independence, fully developed

internal

resources, and a high national culture do

the arts finally attain, as it

were,

their

majority, and enter upon a truly national

growth.

These

facts are abundantly

illustrated by the architectural history

of the United

States.

The only one among the British

colonies to attain political

independence, it is

the

only one among them whose

architecture has as yet entered upon an

independent

course

of development, and this only within the

last twenty-five or thirty years.

Nor

has

even this development produced as yet a

distinctive local style. It

has, however,

originated

new constructive methods, new types of

buildings, and a distinctively

American

treatment of the composition and the

masses; the decorative details

being

still,

for the most part, derived from

historic precedents. The architecture of

the

other

British colonies has

retained its provincial

character, though producing from

time

to time individual works of

merit. In South America and

Mexico the only

buildings

of importance are Spanish,

French, or German in style,

according to the

nationality

of the architects employed. The following

sketch of American

architecture

refers,

therefore, exclusively to its

development in the United States.

FORMATIVE

PERIOD. Buildings

in stone were not undertaken by the

early English

colonists.

The more important structures in the

Southern and Dutch colonies were

of

brick

imported from Europe. Wood

was, however, the material

most commonly

employed,

especially in New England, and its

use determined in large

measure the

form

and style of the colonial architecture.

There was little or no striving

for

architectural

elegance until well into the eighteenth century, when

Wren's influence

asserted

itself in a modest way in the Middle and

Southern colonies. The very

simple

and

unpretentious town-hall at Williamsburg,

Va., and St. Michael's,

Charleston, are

attributed

to him; but the most that can be said for

these, as for the brick

churches

and

manors of Virginia previous to 1725, is

that they are simple in design

and

pleasing

in proportion, without special

architectural elegance. The same is true

of the

wooden

houses and churches of New England of the

period, except that they are

even

simpler

in design.

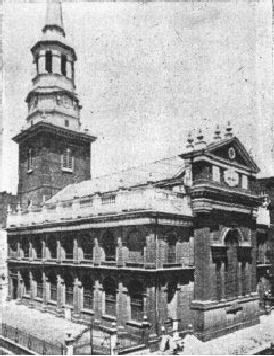

FIG.

218.--CHRIST CHURCH,

PHILADELPHIA.

From

1725 to 1775 increased population and

wealth along the coast

brought about

a

great advance in architecture,

especially in churches and in the

dwellings of the

wealthy.

During this period was developed the

Colonial

style,

based on that of the

reigns

of Anne and the first two Georges in

England, and in church architecture

on

the

models set by Wren and

Gibbs. All the details were,

however, freely modified

by

the

general employment of wood. The

scarcity of architects trained in Old

World

traditions

contributed to this departure from

classic precision of form. The

style,

especially

in interior design, reflected the

cultured taste of the colonial

aristocracy in

its

refined treatment of the woodwork. But

there was little or no architecture of

a

truly

monumental character. Edifices of

stone were singularly few, and

administrative

buildings

were small and modest, owing

to insufficient grants from the Crown,

as

well

as to the poverty of the colonies.

The

churches of this period include a number

of interesting designs,

especially

pleasing

in the forms of their steeples. The

"Old

South" at

Boston (now a museum),

Trinity

at Newport, and St.

Paul's at New

York--one of the few built of stone

(1764)--are

good examples of the style.

Christ

Church at

Philadelphia (172735,

by

Dr. Kearsley) is another example,

historically as well as architecturally

interesting

(Fig.

218); and there are scores of

other churches almost

equally noteworthy,

scattered

through New England, Maryland, Virginia, and the

Middle States.

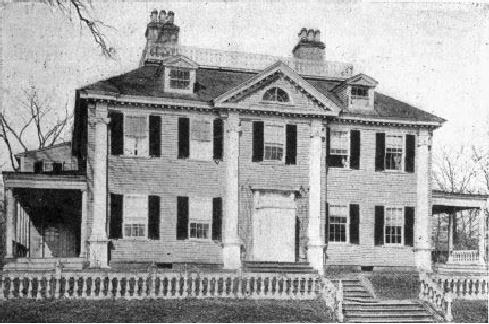

FIG.

219.--CRAIGIE (LONGFELLOW) HOUSE,

CAMBRIDGE.

DWELLINGS.

These

reflect better than the churches the

varying tastes of the

different

colonies. Maryland and Virginia abound in

fine brick manor-houses,

set

amid

extensive grounds walled in and

entered through iron gates of artistic

design.

The

interior finish of these

houses was often elaborate

in conception and admirably

executed.

Westover (1737), Carter's Grove (1737) in

Virginia, and the Harwood and

Hammond

Houses at Annapolis, Md. (1770), are

examples. The majority of the New

England

houses were of wood, more

compact in plan, more varied

and picturesque in

design

than those of the South, but wanting

somewhat of their stateliness. The

interior

finish of wainscot, cornices,

stairs, and mantelpieces shows,

however, the

same

general style, in a skilful and artistic

adaptation of classic forms to the

slender

proportions

of wood construction. Externally the

orders appear in porches and

in

colossal

pilasters, with well designed

entablatures, and windows of Italian

model.

The

influence of the Adams and Sheraton

furniture is doubtless to be seen in

these

quaint

and often charming versions of

classic motives. The Hancock

House, Boston

(of

stone, demolished); the Sherburne

House, Portsmouth (1730); Craigie

House,

Cambridge

(1757, Fig. 219); and Rumford House,

North Woburn (Mass.), are

typical

examples.

In

the Middle States architectural activity

was chiefly centred in

Philadelphia and

New

York, and one or two other towns, where a

number of manor-houses, still

extant,

attest the wealth and taste of the

time. It is noticeable that the veranda

or

piazza

was confined to the Southern

States, but that the climate seems to

have had

little

influence on the forms of roofs.

These were gambrelled,

hipped, gabled, or flat,

alike

in the North and South, according to

individual taste.

PUBLIC

BUILDINGS. Of

public and monumental architecture this

period has little

to

show. Large cities did not exist; New

York, Boston, and Philadelphia were

hardly

more

than overgrown villages. The public

buildings--court-houses and town-halls--

were

modest and inexpensive structures. The

Old State House and Faneuil Hall

at

Boston,

the Town Hall at Newport (R.I.), and Independence Hall

at Philadelphia, the

best

known of those now extant, are not

striking architecturally. Monumental

design

was

beyond the opportunities and means of the

colonies. It was in their churches,

all

of

moderate size, and in their

dwellings that the colonial builders

achieved their

greatest

successes; and these works

are quaint, charming, and

refined, rather than

impressive

or imposing.

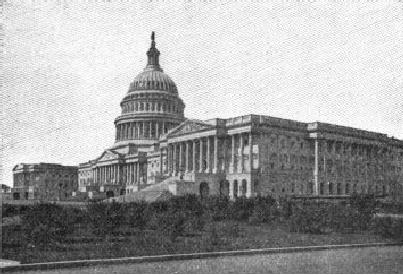

FIG.

220.--NATIONAL CAPITOL,

WASHINGTON.

To

the latter part of the colonial period

belong a number of interesting

buildings

which

remain as monuments of Spanish rule in

California, Florida, and the

Southwest.

The old Fort S. Marco, now Fort Marion

(16561756), and the Catholic

cathedral

(1793; after the fire of 1887 rebuilt in

its original form with the

original

fa�ade

uninjured), both at St. Augustine,

Fla.; the picturesque buildings of

the

California

missions (mainly 17691800), the

majority of them now in ruins;

scattered

Spanish churches in California,

Arizona, and New Mexico, and a few

unimportant

secular buildings, display

among their modern and American

settings a

picturesque

and interesting Spanish aspect and

character, though from the point of

view

of architectural detail they represent

merely a crude phase of

the

Churrigueresque

style.

EARLY

REPUBLICAN PERIOD. Between

the Revolution and the War of 1812,

under

the new conditions of independence and

self-government, architecture took

on

a

more monumental character.

Buildings for the State and National

administrations

were

erected with the rapidly increasing

resources of the country. Stone was

more

generally

used; colonnades, domes, and

cupolas or bell-towers, were

adopted as

indispensable

features of civic architecture. In

church-building the Wren-Gibbs

type

continued

to prevail, but with greater correctness

of classic forms. The gambrel

roof

tended

to disappear from the houses of this

period, and there was some

decline in

the

refinement and delicacy of the details of

architecture. The influence of the

Louis

XVI.

style is traceable in many cases, as in

the New York City Hall (180312, by

McComb

and

Mangin),

one of the very best designs of the

time, and in the delicate

stucco-work

and interior finish of many houses, The

original Capitol

at

Washington--

the

central portion of the present

edifice--by Thornton,

Hallet, and

B.

H. Latrobe

(17931830;

Fig. 220), the State

House at

Boston (1795, by Bulfinch), and

the

University

of Virginia, at Charlotteville, by

Thomas

Jefferson (1817;

recently

destroyed

in part by fire), are the most

interesting examples of the classic

tendencies

of

this period. Their freedom from the

rococo vulgarities generally

prevalent at the

time

in Europe is noticeable.

FIG.

221.--CUSTOM HOUSE, NEW

YORK.

THE

CLASSIC REVIVAL. The

influence of the classic revivals of

Europe began to

appear

before the close of this period, and

reached its culmination

about 183040.

It

left its impress most

strongly on our Federal architecture,

although it invaded

domestic

architecture, producing countless

imitations, in brick and wooden

houses,

of

Grecian colonnades and porticos. One of

its first-fruits was the

White House, or

Executive

Mansion, at Washington, by Hoban

(1792),

recalling the large

English

country

houses of the time. The Treasury

and

Patent

Office buildings

at Washington,

the

Philadelphia Mint, the Sub-treasury

and

Custom

House at New York

(the latter

erected

originally for a bank; Fig. 221), and the

Boston

Custom House are

among

the

important Federal buildings of this

period. Several State

capitols were also

erected

under the same influence; and the Marine

Exchange and Girard

College at

Philadelphia

should also be mentioned as

conspicuous examples of the

pseudo-Greek

style.

The last-named building is a Corinthian

dormitory, its tiers of small

windows

contrasting

strangely with its white marble

columns. These classic

buildings were

solidly

and carefully constructed, but lacked the

grace, cheerfulness, and

appropriateness

of earlier buildings. The Capitol at

Washington was during

this

period

greatly enlarged by terminal

wings with fine Corinthian

porticos, of Roman

rather

than Greek design. The Dome, by

Walters,

was not added until 185873; it

is

a

successful and harmonious

composition, nobly completing

the building.

Unfortunately,

it is an afterthought, built of iron painted to

simulate marble, the

substructure

being inadequate to support a

dome of masonry. The Italian or

Roman

style

which it exemplified, in time superseded

the less tractable Greek

style.

THE

WAR PERIOD. The

period from 1850 to 1876 was one of

intense political

activity

and rapid industrial progress. The

former culminated in the terrible

upheaval

of

the civil war; the latter in the

completion of the Pacific Railroad (1869)

and a

remarkable

development of the mining resources and

manufactures of the country. It

was

a period of feverish commercial

activity, but of artistic stagnation, and

witnessed

the

erection of but few buildings of

architectural importance. A number of

State

capitols,

city halls and churches, of considerable

size and cost but of inferior

design,

attest

the decline of public taste and

architectural skill during

these years. The huge

Municipal

Building at Philadelphia and the still

unfinished Capitol at Albany

are full

of

errors of planning and detail which

twenty-five years of elaboration

have failed to

correct.

Next to the dome of the Capitol at

Washington, completed during

this

period,

of which it is the most signal

architectural achievement, its

most notable

monument

was the St.

Patrick's Cathedral at New York,

by Renwick; a

Gothic

church

which, if somewhat cold and mechanical in

detail, is a stately and

well-

considered

design. Its west front and spires

(completed 1886) are

particularly

successful.

Trinity Church (1843, by Upjohn) and

Grace Church (1840, by

Renwick),

though of earlier date, should be

classed with this cathedral as

worthy

examples

of modern Gothic design.

Indeed, the churches designed in this

style by a

few

thoroughly trained architects

during this period are the

most creditable and

worthy

among its lesser

productions. In general an

undiscriminating eclecticism of

style

prevailed, unregulated by sober

taste or technical training. The

Federal

buildings

by Mullett

were

monuments of perverted design in a

heavy and inartistic

rendering

of French Renaissance motives. The New

York Post Office and the

State,

Army

and Navy Department building at

Washington are examples of this

style.

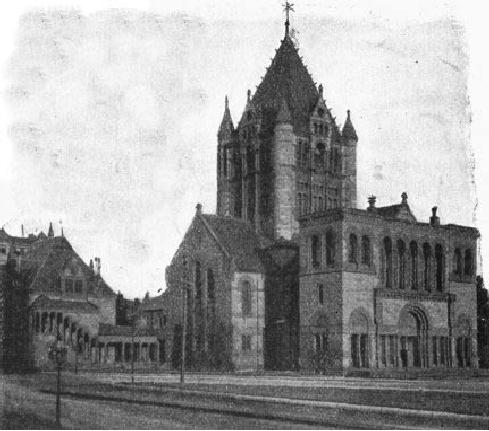

FIG.

222.--TRINITY CHURCH,

BOSTON.

THE

ARTISTIC AWAKENING. Between

1870 and 1880 a remarkable series

of

events

exercised a powerful influence on the

artistic life of the United States.

Two

terrible

conflagrations in Chicago (1871) and

Boston (1872) gave

unexampled

opportunities

for architectural improvement and greatly

stimulated the public

interest

in

the art. The feverish and abnormal

industrial activity which followed the

war and

the

rapid growth of the parvenu spirit

were checked by the disastrous "panic"

of

1873.

With the completion of the Pacific

railways and the settlement of new

communities

in the West, industrial prosperity, when

it returned, was established

on

a

firmer basis. An extraordinary

expansion of travel to Europe

began to disseminate

the

seeds of artistic culture

throughout the country. The successful

establishment of

schools

of architecture in Boston (1866) and

other cities, and the opening

or

enlargement

of art museums in New York, Boston,

Philadelphia, Baltimore,

Detroit,

Milwaukee,

and elsewhere, stimulated the artistic

awakening which now manifested

itself.

In architecture the personal influence of

two men, trained in the Paris

�cole

des

Beaux-Arts, was especially felt--of

R.

M. Hunt (182795)

through his words and

deeds

quite as much as through his works; and

of H.

H. Richardson (182886)

predominantly

through his works. These two men, with

others of less fame but

of

high

ideals and thorough culture, did much to

elevate architecture as an art in

the

public

esteem. To all these influences new

force was added by the

Centennial

Exhibition

at Philadelphia (1876). Here for the

first time the American

people were

brought

into contact, in their own land, with the products of

European and Oriental

art.

It was to them an artistic revelation,

whose results were prompt and

far-

reaching.

Beginning first in the domain of

industrial and decorative art,

its

stimulating

influence rapidly extended to

painting and architecture, and

with

permanent

consequences. American students

began to throng the centres of Old

World

art, while the setting of higher

standards of artistic excellence at

home, and

the

development of important art-industries,

were other fruits of this

artistic

awakening.

The recent Columbian Exhibition at

Chicago (1893), its latest and

most

important

manifestation, has added a new

impulse to the movement, especially

in

architecture.

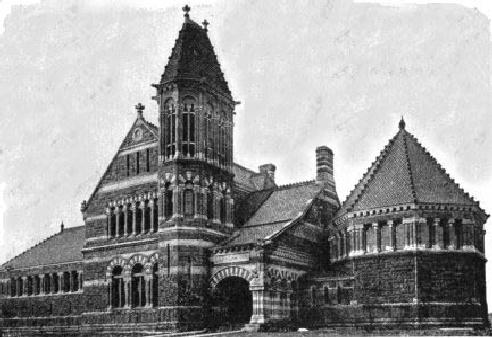

FIG.

223.--LIBRARY AT WOBURN,

MASS.

STYLE

IN RECENT ARCHITECTURE. The

rapid increase in the number of

American

architects trained in Paris or under the

indirect influence of the �cole

des

Beaux-Arts

has been an important factor

in recent architectural progress. Yet it

has

by

no means imposed the French

academic formul� upon American

architecture. The

conditions,

materials, and constructive processes

here prevailing, and above all

the

eclecticism

of the public taste, have

prevented this. The French

influence is perceived

rather

in a growing appreciation of monumental

design in the planning,

composition,

and

setting of buildings, than in any direct

imitation of French models. The

Gothic

revival

which prevailed more or less widely from

1840 to 1875, as already noticed,

and

of which the State

Capitol at Hartford

(Conn.; 187578), and the Fine

Arts

Museum

at

Boston, were among the last

important products, was

generally confined

to

church architecture, for which Gothic

forms are still largely

employed, as in the

Protestant

Cathedral

of

All

Saints now

building at Albany (N.Y.), by an

English

architect.

For the most part the works of the

last twenty years show a more or

less

judicious

eclecticism, the choice of style

being determined partly by the person

and

training

of the designer, partly by the nature of the

building. The powerfully

conceived

works of Richardson, in a free

version of the French Romanesque, for

a

time

exercised a wide influence,

especially among the younger

architects. Trinity

business

buildings, and finally the impressive

County

Buildings at

Pittsburgh (Pa.),

all

treated in this style, are

admirable rather for the strong

individuality of their

designer,

displayed in their vigorous composition,

than on account of the historic

style

he employed (Fig. 223). Yet it appeared

in his hands so flexible and

effective

that

it was widely imitated. But if easy to

use, it is most difficult to

use well; its

forms

are too massive for ordinary

purposes, and in the hands of inferior

designers it

was

so often travestied that it has now

lost its wide popularity.

While a number of

able

architects have continued to

use it effectively in ecclesiastical,

civic, and even

commercial

architecture, it is being generally

superseded by various forms of

the

Renaissance.

Here also a wide eclecticism

prevails, the works of the same

architect

often

varying from the gayest Francis I.

designs in domestic architecture, or

free

adaptations

of Quattrocento details for theatres and

street architecture, to the

most

formal

classicism in colossal

exhibition-buildings, museums, libraries,

and the like.

Meanwhile

there are many more or less

successful ventures in other

historic styles

applied

to public and private edifices.

Underlying this apparent confusion,

almost

anarchy

in the use of historic styles, the

careful observer may detect

certain

tendencies

crystallizing into definite form. New

materials and methods of

construction,

increased attention to detail, a

growing sense of

monumental

requirements,

even the development of the elevator as a

substitute for the grand

staircase,

are leaving their mark on the planning,

the proportions, and the artistic

composition

of American buildings, irrespective of

the styles used. The art is with

us

in

a state of transition, and open to

criticism in many respects; but it

appears to be

full

of life and promise for the

future.

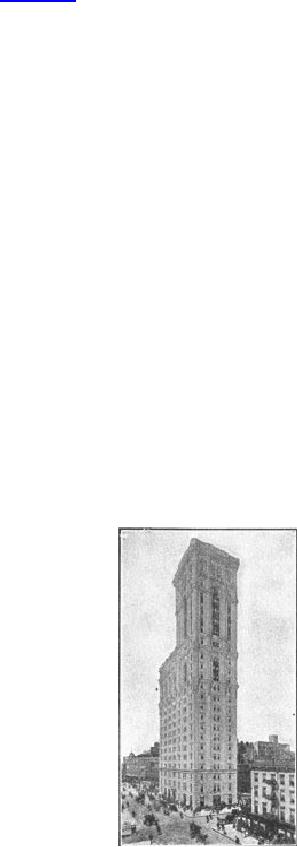

FIG.

224.--"TIMES" BUILDING, NEW

YORK.

COMMERCIAL

BUILDINGS. This

class of edifices has in our

great cities

developed

wholly

new types, which have taken

shape under four imperative influences.

These

are

the demand for fire-proof construction,

the demand for well-lighted offices,

the

introduction

of elevators, and the concentration of

business into limited areas,

within

which

land has become inordinately

costly. These causes have

led to the erection of

buildings

of excessive height (Fig. 224); the

more recent among them

constructed

with

a framework of iron or steel columns and

beams, the visible walls

being a mere

filling-in.

To render a building of twenty stories

attractive to the eye, especially

when

built

on an irregular site, is a difficult

problem, of which a wholly

satisfactory

solution

has yet to be found. There have

been, however, some notable

achievements

in

this line, in most of which the principle

has been clearly recognized

that a lofty

building

should have a well-marked

basement or pedestal and a somewhat

ornate

crowning

portion or capital, the intervening

stories serving as a die or

shaft and

being

treated with comparative simplicity. The

difficulties of scale and of

handling

one

hundred and fifty to three hundred windows of uniform

style have been

surmounted

with conspicuous skill (American

Surety Building and

Broadway

Chambers,

New York; Ames Building, Boston;

Carnegie Building, Pittsburgh;

Union

Trust,

St. Louis).

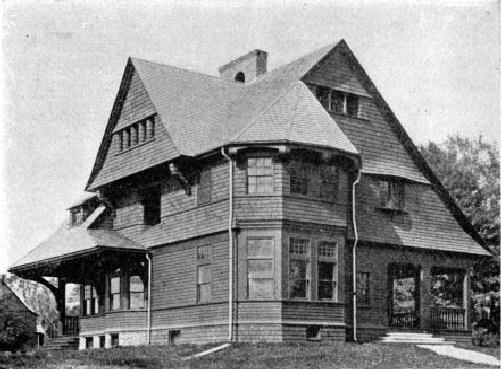

FIG.

225.--COUNTRY HOUSE,

MASSACHUSETTS.

In

some cases, especially in

Chicago and the Middle West, the metallic

framework is

suggested

by slender piers between the

windows, rising uninterrupted from

the

basement

to the top story. In others, especially in New York

and the East, the walls

are

treated as in ordinary masonry

buildings. The Chicago school is

marked by a

more

utilitarian and unconventional treatment,

with results which are

often

extremely

bold and effective, but rarely as

pleasing to the eye as those

attained by

the

more conservative Eastern

school. In the details of American

office-buildings

every

variety of style is to be met with; but the

Romanesque and the Renaissance,

freely

modified, predominate. The tendency

towards two or three well-marked

types

in

the external composition of these

buildings, as above suggested,

promises,

however,

the evolution of a style in which the

historic origin of the details will be

a

secondary

matter. Certain Chicago

architects have developed an

original treatment of

architectural

forms by exaggerating some of the

structural lines, by suppressing

the

mouldings

and more familiar historic

forms, and by the free use of flat

surface

ornament.

The Schiller, Auditorium, and Fisher

Buildings, all at Chicago,

Guaranty

Building,

Buffalo, and Majestic Building,

Detroit, are examples of this

personal style,

which

illustrates the untrammelled freedom of

the art in a land without traditions.27

DOMESTIC

ARCHITECTURE. It is in this

field that the most characteristic

and

original

phases of American architecture

are to be met with, particularly in rural

and

suburban

residences. In these the peculiar

requirements of our varying climates

and

of

American domestic life have

been studied and in large

measure met with great

frankness

and artistic appreciation. The broad

staircase-hall, serving often as a

sort

of

family sitting-room, the piazza, and a

picturesque massing of steep

roofs, have

been

the controlling factors in the evolution

of two or three general types

which

appear

in infinite variations. The material

most used is wood, but this

has had less

influence

in the determination of form than might have

been expected. The

artlessness

of the planning, which is arranged to

afford the maximum of convenience

rather

than to conform to any traditional type,

has been the element of

greatest

artistic

success. It has resulted in

exteriors which are the natural outgrowth

of the

interior

arrangements, frankly expressed, without

affectation of style (Fig. 225).

The

resulting

picturesqueness has, however, in many

cases been treated as an end

instead

of

an incidental result, and the affectation

of picturesqueness has in such

designs

become

as detrimental as any affectation of

style. In the internal treatment

of

American

houses there has also

been a notable artistic

advance, harmony of color

and

domestic comfort and luxury being

sought after rather than

monumental effects.

A

number of large city and country houses

designed on a palatial scale

have,

however,

given opportunity for a more

elaborate architecture; notably the

Vanderbilt,

Villard,

and Huntington residences at New York, the great

country-seat of Biltmore,

near

Asheville (N.C.), in the Francis I.

style (by R. M. Hunt), and many

others.

OTHER

BUILDINGS. American

architects have generally

been less successful

in

public,

administrative, and ecclesiastical

architecture than in commercial

and

domestic

work. The preference for small parish

churches, treated as

audience-rooms

rather

than as places of worship, has

interfered with the development of noble

types

of

church-buildings. Yet there are

signs of improvement; and the new

Cathedral

of

St.

John the Divine at New York,

in a modified Romanesque style,

promises to be a

worthy

and monumental building. In semi-public

architecture, such as

hotels,

theatres,

clubs, and libraries, there

are many notable examples of

successful design.

The

Ponce

de Leon Hotel at

St. Augustine, a sumptuous and

imposing pile in a

free

version

of the Spanish Plateresco; the Auditorium

Theatre at Chicago, the

Madison

Square

Garden and the Casino at New York, may be

cited as excellent in

general

conception

and well carried out in detail,

externally and internally. The Century

and

Metropolitan

Clubs at New York, the Boston

Public Library, the

Carnegie Library at

Pittsburgh,

the Congressional

Library at

Washington, and the recently

completed

Minnesota

State

Capitol at

St. Paul, exemplify in

varying degrees of excellence

the

increasing

capacity of American architects for

monumental design. This was

further

shown

in the buildings of the Columbian

Exposition at

Chicago in 1893. These, in

spite

of many faults of detail, constituted an

aggregate of architectural splendor

such

as

had never before been seen

or been possible on this

side the Atlantic. They further

brought

architecture into closer union with the

allied arts and formed an

object

lesson

in the value of appropriate landscape

gardening as a setting to

monumental

structures.

It

should be said, in conclusion, that with

the advances of recent years in

artistic

design

in the United States there has

been at least as great

improvement in scientific

construction.

The sham and flimsiness of the Civil War

period are passing away,

and

solid

and durable building is becoming

more general throughout the country,

but

especially

in the Northeast and in some of the great

Western cities, notably

in

Chicago.

In this onward movement the Federal

buildings--post-offices, custom-

houses,

and other governmental edifices--have

not, till lately, taken high rank.

Although

solidly and carefully constructed,

those built during the period

18751895

were

generally inferior to the best work

produced by private enterprise, or by

State

and

municipal governments. This

was in large part due to

enactments devolving upon

the

supervising architect at Washington the

planning of all Federal buildings, as

well

as

a burden of supervisory and clerical

duties incompatible with the highest

artistic

results.

Since 1898, however, a more

enlightened policy has

prevailed, and a number

of

notable designs for Federal

buildings have been secured

by carefully-conducted

competitions.

27.

See

Appendix,

D and

E.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.