|

RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE |

| << THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY |

| ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS >> |

CHAPTER

XXVI.

RECENT

ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Chateau,

Fergusson. Also Barqui,

L'Architecture

moderne

en France.--Berlin

und seine Bauten (and

a series of similar works on

the

modern

buildings of other German

cities). Daly, Architecture

priv�e du XIXe si�cle.

Garnier,

Le

nouvel Op�ra.

Gourlier, Choix

d'�difices publics.

Licht, Architektur

Deutschlands.

L�bke, Denkm�ler

der Kunst.

L�tzow und Tischler, Wiener

Neubauten.

Narjoux,

Monuments

�lev�s par la ville de Paris,

18501880.

R�ckwardt, Fa�aden

und

Details modernen Bauten.--Sammelmappe

hervorragenden

Concurrenz-Entwurfen.

S�dille,

L'Architecture

moderne.

Selfridge, Modern

French Architecture.

Statham,

Modern

Architecture.

Villars, England,

Scotland, and Ireland (tr.

Henry Frith). Consult

also

Transactions

of the Royal Institute of

British Architects,

and the leading

architectural

journals of recent

years.

MODERN

CONDITIONS. The

nineteenth century has been

pre-eminently an age of

industrial

progress. Its most striking

advances have been along

mechanical, scientific,

and

commercial lines. As a result of this

material progress the general

conditions of

mankind

in civilized countries have

undoubtedly been greatly

bettered. Popular

education

and the printing-press have also

raised the intellectual level of

society,

making

learning the privilege of even the

poorest. Intellectual, scientific,

and

commercial

pursuits have thus largely

absorbed those energies which in

other ages

found

exercise in the creation of artistic

forms and objects. The critical and

sceptical

spirit,

the spirit of utilitarianism and realism,

has checked the free and

general

development

of the creative imagination, at least in

the plastic arts. While in

poetry

and

music there have been

great and noble achievements, the

plastic arts,

including

architecture,

have only of late years

attained a position at all worthy of

the

intellectual

advancement of the times.

Nevertheless

the artistic spirit has

never been wholly crushed out by the

untoward

pressure

of realism and commercialism. Unfortunately it

has repeatedly been

directed

in

wrong channels. Modern arch�ology and the

publication of the forms of

historic

art

by books and photographs have

too exclusively fastened

attention upon the

details

of extinct styles as a source of

inspiration in design. The whole range

of

historic

art is brought within our survey, and while this

has on the one hand

tended

toward

the confusion and multiplication of

styles in modern work, it has on the

other

led

to a slavish adherence to historic

precedent or a literal copying of

historic forms.

Modern

architecture has thus oscillated

between the extremes of

arch�ological

servitude

and of an unreasoning eclecticism. In the

hands of men of inferior

training

the

results have been deplorable

travesties of all styles, or meaningless

aggregations

of

ill-assorted forms.

An

important factor in this demoralization

of architectural design has

been the

development

of new constructive methods, especially

in the use of iron and steel. It

has

been impossible for modern

designers, in their treatment of style,

to keep pace

with

the rapid changes in the structural

use of metal in architecture. The

roofs of

vast

span, largely composed of

glass, which modern methods of

trussing have made

possible

for railway stations, armories, and

exhibition buildings; the

immense

unencumbered

spaces which may be covered by them; the

introduction and

development,

especially in the United States, of the

post-and-girder system of

construction

for high buildings, in which the external

walls are a mere screen

or

filling-in;

these have revolutionized

architecture so rapidly and completely

that

architects

are still struggling and

groping to find the solution of many of

the

problems

of style, scale, and composition which

they have brought

forward.

Within

the last thirty years, however,

architecture has, despite

these new conditions,

made

notable advances. The artistic

emulation of repeated international

exhibitions,

the

multiplication of museums and schools of

art, the general advance in

intelligence

and

enlightenment, have all contributed to

this artistic progress. There

appears to be

more

of the artistic and intellectual quality

in the average architecture of the

present

time,

on both sides of the Atlantic, than at any

previous period in this century.

The

futility

of the arch�ological revival of extinct

styles is generally recognized.

New

conditions

are gradually procuring the

solution of the very problems they

raise.

Historic

precedent sits more lightly on the

architect than formerly, and the

essential

unity

of principle underlying all good

design is coming to be better

understood.26

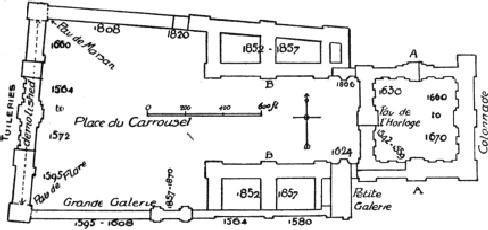

FIG.

208.--PLAN OF LOUVRE AND TUILERIES,

PARIS.

A,

A, the Old Louvre, so

called; B, B, the New

Louvre.

FRANCE.

It is in

France, Germany (including

Austria), and England that the

architectural

progress of this period in Europe

has been most marked. We

have

already

noticed the results of the classic

revivals in these three

countries. Speaking

broadly,

it may be said that in France the

influence of the �cole

des Beaux-Arts,

while

it

has tended to give greater

unity and consistency to the national

architecture, and

has

exerted a powerful influence in

behalf of refinement of taste and

correctness of

style,

has also stood in the way of a

free development of new ideas.

French

architecture

has throughout adhered to the

principles of the Renaissance, though

the

style

has during this century been

modified by various influences. The

first of these

was

the N�o-Grec movement, alluded to in the

last chapter, which broke the

grip of

Roman

tradition in matters of detail and

gave greater elasticity to the

national style.

Next

should be mentioned the Gothic

movement represented by

Viollet-le-Duc,

Lassus,

Ballu, and their followers.

Beginning about 1845, it produced

comparatively

few

notable buildings, but gave a

great impulse to the study of medi�val

arch�ology

and

the restoration of medi�val monuments.

The churches of Ste. Clothilde and

of

St.

Jean de Belleville, at Paris, and the

reconstruction of the Ch�teau de

Pierrefonds,

were

among its direct results.

Indirectly it led to a freer and

more rational

treatment

of

constructive forms and materials than

had prevailed with the academic

designers.

The

church of St.

Augustin, by

Baltard, at

Paris, illustrates this in its

use of iron and

brick

for the dome and vaulting, and the

College

Chaptal, by

E.

Train, in

its

decorative

treatment of brick and tile

externally. The general adoption of iron

for

roof-trusses

and for the construction of markets and

similar buildings tended

further

in

the same direction, the Halles

Centrales at

Paris, by Baltard,

being a notable

example.

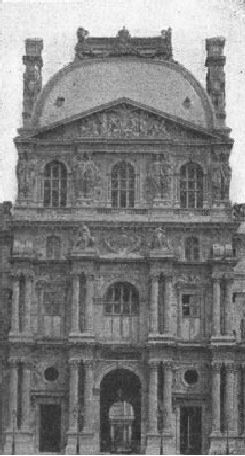

FIG.

209.--PAVILION OF RICHELIEU,

LOUVRE.

THE

SECOND EMPIRE. The

reign of Napoleon III. (185270) was

a period of

exceptional

activity, especially in Paris. The

greatest monument of his reign

was the

completion

of the Louvre

and

Tuileries, under

Visconti

and

Lefuel,

including the

remodelling

of the pavilions de Flore and de Marsan.

The new portions constitute the

most

notable example of modern

French architecture, and the manner in

which the

two

palaces were united deserves

high praise. In spite of certain

defects, this work is

marked

by a combination of dignity, richness, and

refinement, such as are

rarely

found

in palace architecture (Figs. 208, 209).

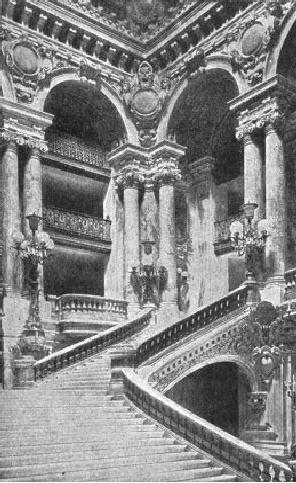

The New

Opera (186375),

by

Garnier

(d. 1898),

stands next to the Louvre in importance

as a national monument.

It

is by far the most sumptuous building for

amusement in existence, but in purity

of

detail

and in the balance and restraint of its

design it is inferior to the work

of

Visconti

and Lefuel (Fig. 210). To this reign

belong the Palais de l'Industrie, by

Viel,

built

for the exhibition of 1855, and several

great railway stations (Gare

du Nord, by

Hitorff,

Gare de l'Est, Gare

d'Orl�ans, etc.), in which the modern

French version of

the

Renaissance was applied with

considerable skill to buildings

largely constructed

of

iron and glass. Town halls and theatres

were erected in great

numbers, and in

decorative

works like fountains and

monuments the French were

particularly

successful.

The fountains of St.

Michel,

Cuvier, and Moli�re, at Paris, and

of

Longchamps, at

Marseilles (Fig. 211), illustrate the

fertility of resource and

elegance

of

detailed treatment of the French in this

department. Mention should also

here be

made

of the extensive enterprises carried out

by Napoleon III., in rectifying

and

embellishing

the street-plan of Paris by new avenues

and squares on a vast

scale,

adding

greatly to the monumental splendor of the

city.

FIG.

210.--GRAND STAIRCASE OF THE

OPERA, PARIS.

THE

REPUBLIC. Since

the disasters of 1870 a number of important

structures have

been

erected, and French architecture

has shown a remarkable vitality and

flexibility

under

new conditions. Its productions have in

general been marked by a

refined taste

and

a conspicuous absence of eccentricity and

excess; but it has for the most

part

trodden

in well-worn paths. The most

notable recent monuments

are, in church

architecture,

the Sacr�-Coeur, at

Montmartre, by Abadie, a

votive church inspired

from

the Franco-Byzantine style of Aquitania;

in civil architecture the new H�tel

de

Ville, at

Paris, by Ballu

and

D�perthes,

recalling the original structure

destroyed by

the

Commune, but in reality an original

creation of great merit; in

scholastic

architecture

the new �cole de M�decine, and the new

Sorbonne, by

N�not, and

in

other

branches of the art the metal-and-glass

exhibition buildings of 1878,

1889,

and

1900. In the last of these the striving

for originality and the effort to

discard

traditional

forms reached the extreme,

although accompanied by much very

clever

detail

and a masterly use of color-decoration.

To these should be added

many

noteworthy

theatres, town-halls, court-houses, and

pr�fectures

in

provincial cities,

and

commemorative columns and monuments

almost without number. In street

architecture

there is now much more variety and

originality than formerly,

especially

in

private houses, and the reaction

against the orders and against

traditional methods

of

design has of late been

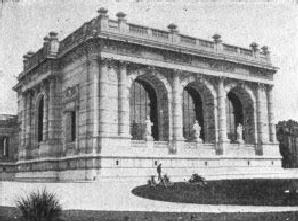

growing stronger. The chief

excellence of modern

French

architecture

lies in its rational

planning, monumental spirit, and

refinement of detail

(Fig.

212).

FIG.

211.--FOUNTAIN OF LONGCHAMPS,

MARSEILLES.

GERMANY

AND AUSTRIA. German

architecture has been more

affected during the

past

fifty years by the arch�ological spirit

than has the French. A

pronounced

medi�val

revival partly accompanied, partly

followed the Greek revival in

Germany,

and

produced a number of churches and a few

secular buildings in the

basilican,

Romanesque,

and Gothic styles. These are

less interesting than those in the

Greek

style,

because medi�val forms are

even more foreign to modern

needs than the

classic,

being compatible only with systems of

design and construction which are

no

longer

practicable. At Munich the Auekirche, by

Ohlmuller, in an

attenuated Gothic

style;

the Byzantine Ludwigskirche, and

Ziebland's

Basilica

following Early

Christian

models;

the Basilica by H�bsch, at

Bulach, and the Votive Church at

Vienna (1856)

by

H. Von Ferstel (18281883) are

notable neo-medi�val monuments. The

last-

named

church may be classed with Ste. Clothilde

at Paris, and St. Patrick's

Cathedral

at

New York, all three being of

approximately the same size and

general style,

recalling

St. Ouen at Rouen. They are

correct and elaborate, but more or

less cold

and

artificial.

FIG.

212.--MUS�E GALLI�RA,

PARIS.

More

successful are many of the German

theatres and concert halls, in

which

Renaissance

and classic forms have been

freely used. In several of

these the attempt

has

been made to express by the

external form the curvilinear plan of the

auditorium,

as

in the Dresden

Theatre, by

Semper

(1841;

Fig. 213), the theatre at Carlsruhe,

by

H�bsch,

and the double winter-summer Victoria

Theatre, at

Berlin, by Titz. But

the

practical

and �sthetic difficulties involved in

this treatment have caused

its general

abandonment.

The Opera

House at

Vienna, by Siccardsburg

and

Van

der Null

(186169),

is rectangular in its masses, and but for

a certain triviality of

detail

would

rank among the most successful

buildings of its kind. The new Burgtheater

in

the

same city is a more elaborately

ornate structure in Renaissance

style, somewhat

florid

and overdone.

Modern

German architecture is at its

best in academic and residential

buildings. The

Bauschule, at

Berlin, by Schinkel, in which brick is

used in a rational and

dignified

design

without the orders; the Polytechnic

School, at Z�rich, by Semper;

university

buildings,

and especially buildings for technical

instruction, at Carlsruhe,

Stuttgart,

Strasburg,

Vienna, and other cities, show a

monumental treatment of the exterior

and

of

the general distribution, combined with a

careful study of practical

requirements.

In

administrative buildings the Germans

have hardly been as successful; and the

new

Parliament

House, at

Berlin, by Wallot, in

spite of its splendor and

costliness, is

heavy

and unsatisfactory in detail. The larger

cities, especially Berlin,

contain many

excellent

examples of house architecture,

mostly in the Renaissance style,

sufficiently

monumental

in design, though usually, like most

German work, inclined to

heaviness

of

detail. The too free use of

stucco in imitation of stone is

also open to

criticism.

FIG.

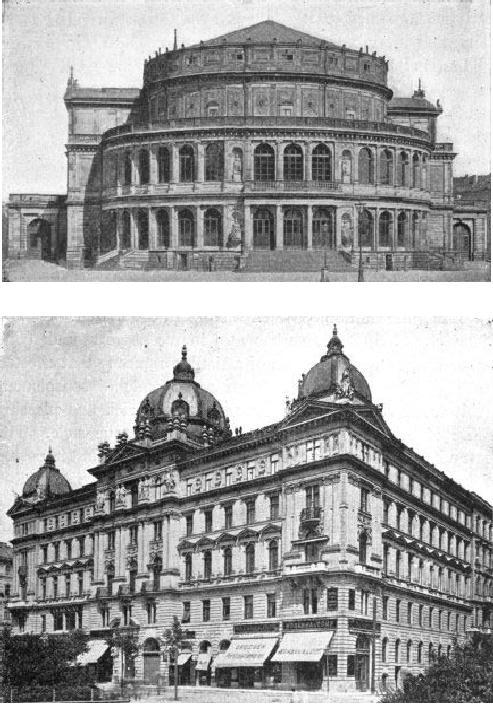

213.--THEATRE AT DRESDEN.

FIG.

214.--BLOCK OF DWELLINGS

(MARIE-THERESIENHOF), VIENNA.

VIENNA.

During the

last thirty years Vienna has

undergone a transformation which

has

made it the rival of Paris as a stately

capital. The remodelling of the

central

portion,

the creation of a series of magnificent

boulevards and squares, and the

grouping

of the chief state and municipal

buildings about these upon a

monumental

scheme

of arrangement, have given the city an

unusual aspect of splendor.

Among

the

most important monuments in this

group are the Parliament

House, by

Hansen,

and

the Town

Hall, by

Schmidt.

This latter is a Neo-Gothic

edifice of great size

and

pretentiousness,

but strangely thin and meagre in detail,

and quite out of harmony

with

its surroundings. The university and

museums are massive piles in

Renaissance

style;

and it is the Renaissance rather than the

classic or Gothic revival

which

prevails

throughout the new city. The great blocks

of residences and apartments

(Fig.

214)

which line its streets are

highly ornate in their architecture, but

for the most

part

done in stucco, which fails

after all to give the aspect of

solidity and durability

which

it seeks to counterfeit.

The

city of Buda-Pesth

has

also in recent years

undergone a phenomenal

transformation

of a similar nature to that effected in

Vienna, but it possesses

fewer

monuments

of conspicuous architectural interest.

The Synagogue

is the

most noted

of

these, a rich and pleasing edifice of

brick in a modified Hispano-Moresque

style.

FIG.

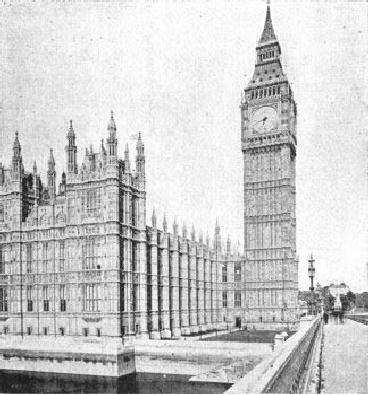

215.--HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT, WESTMINSTER,

LONDON.

GREAT

BRITAIN. During the

closing years of the Anglo-Greek

style a coterie of

enthusiastic

students of British medi�val

monuments--arch�ologists rather

than

architects--initiated

a movement for the revival of the

national Gothic

architecture.

The

first fruits of this movement, led by

Pugin, Brandon, Rickman, and

others (about

183040),

were seen in countless

pseudo-Gothic structures in which the

pointed

arches,

buttresses, and clustered shafts of

medi�val architecture were

imitated or

parodied

according to the designer's ability, with

frequent misapprehension of

their

proper

use or significance. This

unintelligent misapplication of Gothic

forms was,

however,

confined to the earlier stages of the

movement. With increasing light

and

experience

came a more correct and

consistent use of the medi�val

styles, dominated

by

the same spirit of arch�ological

correctness which had produced the

classicismo

of

the Late Renaissance in Italy. This

spirit, stimulated by extensive

enterprises in

the

restoration of the great medi�val

monuments of the United Kingdom, was

fatal

to

any free and original development of the

style along new lines. But it

rescued

church

architecture from the utter meanness and

debasement into which it had

fallen,

and established a standard of taste which

reacted on all other branches

of

design.

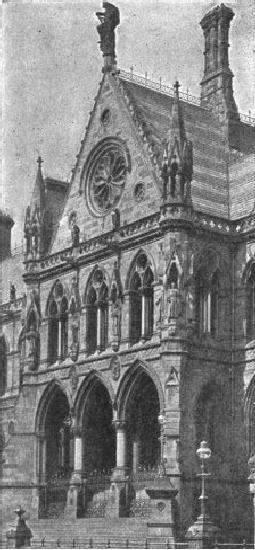

FIG.

216.--ASSIZE COURTS, MANCHESTER.

DETAIL.

THE

VICTORIAN GOTHIC. Between

1850 and 1870 the striving

after

arch�ological

correctness gave place to the

more rational effort to

adapt Gothic

principles

to modern requirements, instead of

merely copying extinct

styles. This

effort,

prosecuted by a number of architects of

great intelligence, culture,

and

earnestness

(Sir Gilbert Scott, George

Edmund Street, William

Burges, and others),

resulted

in a number of extremely interesting

buildings. Chief among these

in size

and

cost stand the Parliament

Houses at

Westminster, by Sir

Charles Barry (begun

1839),

in the Perpendicular style. This

immense structure (Fig. 215),

imposing in its

simple

masses and refined in its

carefully studied detail, is the

most successful

monument

of the Victorian Gothic style. It

suffers, however, from the want of

proper

relation

of scale between its

decorative elements and the vast

proportions of the

edifice,

which belittle its component

elements. It cannot, on the whole, be

claimed as

a

successful vindication of the claims of

the promoters of the style as to

the

adaptability

of Gothic forms to structures

planned and built after the

modern

fashion.

The Assize

Courts at

Manchester (Fig. 216), the New

Museum at

Oxford,

the

gorgeous Albert

Memorial at

London, by Scott, and the

New

Law Courts at

London,

by Street,

are all conspicuous illustrations of the

same truth. They are

conscientious,

carefully studied designs in

good taste, and yet wholly unsuited

in

style

to their purpose. They are

like labored and scholarly

verse in a foreign

tongue,

correct

in form and language, but lacking the

naturalness and charm of true and

unfettered

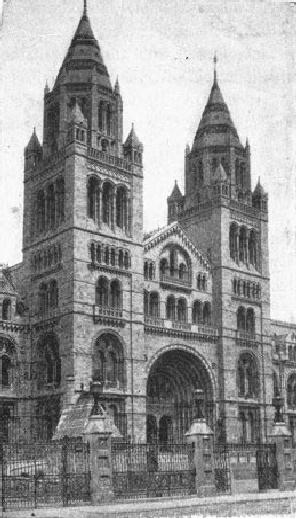

inspiration. A later essay of the

same sort in a slightly

different field is the

Natural

History Museum at

South Kensington, by Waterhouse

(1879), an

imposing

building

in a modified Romanesque style

(Fig. 217).

FIG.

217.--NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM,

LONDON.

OTHER

WORKS. The

Victorian Gothic style

responded to no deep and

general

movement

of the popular taste, and, like the

Anglo-Greek style, was

doomed to

failure

from the inherent incongruity between

modern needs and medi�val

forms.

Within

the last twenty years there

has been a quite general

return to Renaissance

principles,

and the result is seen in a large number

of town-halls, exchanges,

museums,

and colleges, in which Renaissance forms,

with and without the orders,

have

been treated with increasing

freedom and skilful adaptation to the

materials and

special

requirements of each case. The

Albert Memorial Hall (1863, by

General

Scott)

may be taken as an early instance of this

movement, and the Imperial

Institute

(Colonial

offices), by Collcutt, and Oxford Town Hall, by

Aston Webb, as

among

its latest manifestations. In

domestic architecture the so-called

Queen Anne

style

has been much in vogue, as

practised by Norman Shaw, Ernest

George, and

others.

It is really a modern style,

originating in the imitation of the

modified

Palladian

style as used in the brick

architecture of Queen Anne's

time, but freely and

often

artistically altered to meet

modern tastes and

needs.

In

its emancipation from the mistaken

principles of arch�ological revivals, and

in its

evidences

of improved taste and awakened

originality, contemporary

British

architecture

shows promise of good things

to come. It is still inferior to the

French in

the

monumental quality, in technical resource

and refinement of decorative

detail.

ELSEWHERE

IN EUROPE. In

other European countries

recent architecture shows

in

general

increasing freedom and improved

good taste, but both its

opportunities and

its

performance have been

nowhere else as conspicuous as in

France, Germany, and

England.

The costly Bourse and the vast but

overloaded Palais de Justice at

Brussels,

by

Polaert,

are neither of them conspicuous for

refined and cultivated taste. A

few

buildings

of note in Switzerland, Russia, and

Greece might find mention in a

more

extended

review of architecture, but cannot

here even be enumerated. In

Italy,

especially

at Rome, Milan, Naples, and Turin, there

has been a great activity

in

building

since 1870, but with the exception of the

Monument

to Victor Emmanuel

and

the National Museum at Rome, monumental

arcades and passages at Milan and

Naples,

and Campi

Santi or

monumental cemeteries at Bologna,

Genoa, and one or

two

other places, there has

been almost nothing of real

importance built in Italy of

late

years.

26.

See

Appendix

D.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.