|

THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY |

| << RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL |

| RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE >> |

CHAPTER

XXV.

THE

CLASSIC REVIVALS IN

EUROPE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Fergusson. Also

Chateau, Histoire

et caract�res de

l'architecture

en France;

and L�bke, Geschichte

der Architektur.

(For the most

part,

however,

recourse must be had to the

general histories of architecture,

and to

monographs

on special cities or

buildings.)

THE

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. By the

end of the seventeenth century the

Renaissance,

properly speaking, had run its

course in Europe. The increasing

servility

of

its imitation of antique

models had exhausted its

elasticity and originality.

Taste

rapidly

declined before the growth of the

industrial and commercial spirit in

the

eighteenth

century. The ferment of democracy and the

disquiet of far-reaching

political

changes had begun to preoccupy the

minds of men to the detriment of

the

arts.

By the middle of the eighteenth century,

however, the extravagances of the

Rococo,

Jesuit, and Louis XV. styles had

begun to pall upon the popular

taste. The

creative

spirit was dead, and nothing

seemed more promising as a

corrective for

these

extravagances than a return to classic

models. But the demand was for a

literal

copying

of the arcades and porticos of Rome, to

serve as frontispieces for buildings

in

which

modern requirements should be

accommodated to these antique

exteriors,

instead

of controlling the design. The result

was a manifest gain in the

splendor of

the

streets and squares adorned by

these highly decorative frontispieces,

but at the

expense

of convenience and propriety in the

buildings themselves. While

this

academic

spirit too often sacrificed

logic and originality to an arbitrary

symmetry and

to

the supposed canons of Roman

design, it also, on the other hand,

led to a

stateliness

and dignity in the planning, especially

in the designing of vestibules,

stairs,

and halls, which render many of the

public buildings it produced well

worthy

of

study. The architecture of the Roman

Revival was pompous and

artificial, but

seldom

trivial, and its somewhat

affected grandeur was a

welcome relief from the

dull

extravagance of the styles it

replaced.

THE

GREEK REVIVAL. The

Roman revival was, however,

displaced in England and

Germany

by the Greek Revival, which set in

near the close of the eighteenth

century.

This

was the result of a newly awakened

interest in the long-neglected monuments

of

Attic

art which the discoveries of Stuart and

Revett--sent out in 1732 by the

London

Society

of Dilettanti--had once more

made known to the world. It led to a

veritable

furore

in

England for Greek Doric and Ionic

columns, which were

applied

indiscriminately

to every class of buildings, with utter

disregard of propriety. The

British

taste was at this time at

its lowest ebb, and failed

to perceive the poverty of

Greek

architecture when deprived of its

proper adornments of carving and

sculpture,

which

were singularly lacking in the

British examples. Nevertheless the

Greek style in

England

had a long run of popular favor,

yielding only during the reign of the

present

sovereign

to the so-called Victorian Gothic, a

revival of medi�val forms. In

Germany

the

Greek Revival was

characterized by a more cultivated

taste and a more

rational

application

of its forms, which were

often freely modified to suit

modern needs. In

France,

where the Roman Revival under

Louis XV. had produced fairly

satisfactory

results,

and where the influence of the Royal

School of Fine Arts

(�cole

des Beaux-

Arts)

tended to perpetuate the principles of

Roman design, the Greek

Revival found

no

footing. The Greek forms

were seen to be too severe

and intractable for present

requirements.

About 1830, however, a modified

style of design, known since as

the

N�o-Grec,

was introduced by the exertions of a

small coterie of talented

architects;

and

though its own life was

short, it profoundly influenced French

art in the

direction

of freedom and refinement for a long

time afterward. In Italy there

was

hardly

anything in the nature of a true revival

of either Roman or Greek

forms. The

few

important works of the late

eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries were

conceived

in the spirit of the late Renaissance,

and took from the prevalent revival

of

classicism

elsewhere merely a greater

correctness of detail, not any radical

change of

form

or spirit.

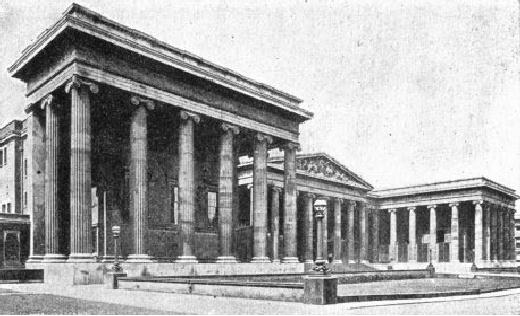

FIG.

198.--BRITISH MUSEUM,

LONDON.

ENGLAND.

There

was, strictly speaking, no

Roman revival in Great

Britain. The

modified

Palladian style of Wren and

Gibbs and their successors continued

until

superseded

by the Greek revival. The first fruit of

the new movement seems to

have

been

the Bank

of England at

London, by Sir

John Soane (1788). In

this edifice the

Greco-Roman

order of the round temple at Tivoli was

closely copied, and applied to

a

long

fa�ade, too low for its

length and with no sufficient stylobate,

but fairly effective

with

its recessed colonnade and

unpierced walls. The British

Museum, by

Robert

Smirke

(Fig.

198), was a more ambitious

essay in a more purely Greek

style. Its

colossal

Ionic colonnade was, however, a

mere frontispiece, applied to a

badly

planned

and commonplace building, from which it cut off

needed light. The

more

modest

but appropriate columnar fa�ade to the

Fitzwilliam

Museum at

Cambridge,

by

Bassevi,

was a more successful

attempt in the same direction,

better proportioned

and

avoiding the incongruity of modern

windows in several stories. These

have

always

been the stumbling-block of the revived

Greek style. The difficulties they

raise

are

avoided, however, in buildings

presenting but two stories, the order

being

applied

to the upper story, upon a high stylobate

serving as a basement. The High

School

and the

Royal Institution at Edinburgh, and the

University at London, by

Wilkins,

are for this reason, if for no other,

superior to the British Museum and

other

many-storied

Anglo-Greek edifices. In spite of all

difficulties, however, the

English

extended

the applications of the style with doubtful

success not only to all manner of

public

buildings, but also to country

residences. Carlton House,

Bowden Park, and

Grange

House are instances of this

misapplication of Greek forms.

Neither did it

prove

more tractable for ecclesiastical

purposes. St.

Pancras's Church

at London, and

several

churches by Thomson

(181775),

in Glasgow, though interesting as

experiments

in such adaptation, are not to be

commended for imitation. The

most

successful

of all British Greek designs is

perhaps St.

George's Hall at

Liverpool (Fig.

199),

whose imposing peristyle and

porches are sufficiently

Greek in spirit and

detail

to

class it among the works of the

Greek Revival. But its great

hall and its interior

composition

are really Roman and not

Greek, emphasizing the teaching of

experience

that

Greek architecture does not

lend itself to the exigencies of

modern civilization to

nearly

the same extent as the

Roman.

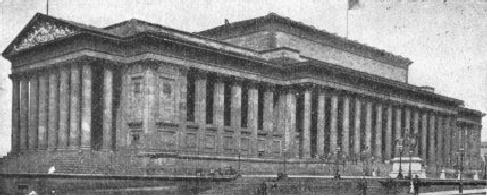

FIG.

199.--ST. GEORGE'S HALL,

LIVERPOOL.

GERMANY.

During the

eighteenth century the classic

revival in Germany, which at

first

followed Roman precedents

(as in the columns carved with

spirally ascending

reliefs

in front of the church of St.

Charles Borromeo, at

Vienna), was directed

into

the

channel of Greek imitation by the

literary works of Winckelmann,

Lessing,

Goethe,

and others, as well as by the interest

aroused by the discoveries of

Stuart

and

Revett. The Brandenburg

Gate at

Berlin (1784, by Langhans) was an

early

example

of this Hellenism in architecture, and

one of its most successful

applications

to

civic purposes. Without precisely

copying any Greek structure, it

was evidently

inspired

from the Athenian Propyl�a, and nothing

in its purpose is foreign to

the

style

employed. The greatest activity in the

style came later, however,

and was

greatly

stimulated by the achievements of

Fr.

Schinkel (17711841),

one of the

greatest

of modern German architects.

While in the domical church of St.

Nicholas at

Potsdam,

he employed Roman forms in a

modernized Roman conception,

and

followed

in one or two other buildings the

principles of the Renaissance,

his

predilections

were for Greek architecture. His

masterpiece was the Museum

at

Berlin,

with an imposing portico of 18 Ionic

columns (Fig. 200). This

building with

its

fine rotunda was excellently

planned, and forms, in conjunction with

the New

Museum

by

Stuhler

(184355),

a noble palace of art, to whose

monumental

requirements

and artistic purpose the Greek

colonnades and pediments were

not

inappropriate.

Schinkel's greatest successor

was Leo

von Klenze (17841864),

whose

more

textual reproductions of Greek

models won him great favor and

wide

employment.

The Walhalla

near

Ratisbon is a modernized Parthenon,

internally

vaulted

with glass; elegant externally, but

too obvious a plagiarism to be

greatly

admired.

The Ruhmeshalle

at Munich, a

double L partly enclosing a colossal

statue

of

Bavaria, and devoted to the commemoration

of Bavaria's great men, is copied

from

no

Greek building, though purely Greek in

design and correct to the smallest

detail.

In

the Glyptothek

(Sculpture

Gallery), in the same city, the one

distinctively Greek

feature

introduced by Klenze, an Ionic portico,

is also the one inappropriate

note in

the

design. The Propyl�a

at Munich, by

the same (Fig. 201), and the Court

Theatre

at

Berlin, by Schinkel, are

other important examples of the

style. The latter is

externally

one of the most beautiful

theatres in Europe, though less

ornate than

many.

Schinkel's genius was here

remarkably successful in adapting

Greek details to

the

exigent difficulties of theatre

design, and there is no suggestion of

copying any

known

Greek building.

FIG.

200.--THE OLD MUSEUM,

BERLIN.

In

Vienna the one

notable monument of the

Classic Revival is

the

Reichsrathsgeb�ude

or

Parliament House, by Th.

Hansen (1843), an

imposing two-

storied

composition with a lofty central

colonnade and lower side-wings,

harmonious

in

general proportions and pleasingly

varied in outline and

mass.

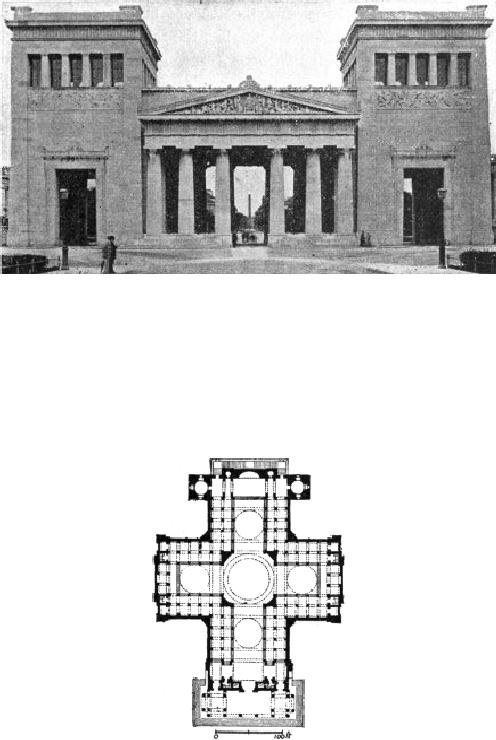

FIG.

201.--THE PROPYL�A,

MUNICH.

In

general, the Greek Revival in

Germany presents the aspect of a

sincere striving

after

beauty, on the part of a limited number of

artists of great talent,

misled by the

idea

that the forms of a dead civilization

could be galvanized into new life in

the

service

of modern needs. The result

was disappointing, in spite of the

excellent

planning,

admirable construction and carefully

studied detail of these

buildings, and

the

movement here as elsewhere

was foredoomed to

failure.

FIG.

202.--PLAN OF PANTH�ON,

PARIS.

FRANCE.

In

France the Classic Revival, as we

have seen, had made its

appearance

during

the reign of Louis XV. in a number of

important monuments which

expressed

the

protest of their authors against the

caprice of the Rococo style then in

vogue. The

colonnades

of the Garde-Meuble, the fa�ade of St.

Sulpice, and the coldly

beautiful

Panth�on

(Figs.

202, 203) testified to the conviction in the

most cultured minds

of

the

time that Roman grandeur was

to be attained only by copying the forms

of

Roman

architecture with the closest possible

approach to correctness. In the

Panth�on,

the greatest ecclesiastical monument of

its time in France

(otherwise

known

as the church of Ste. Gen�vi�ve), the

spirit of correct classicism

dominates the

interior

as well as the exterior. It is a Greek

cross, measuring 362 � 267 feet, with

a

dome

265 feet high, and internally 69

feet in diameter. The four arms

have domical

vaulting

and narrow aisles separated by Corinthian

columns. The whole interior is a

cold

but extremely elegant composition. The

most notable features of the

exterior are

its

imposing portico of colossal

Corinthian columns and the fine

peristyle which

surrounds

the drum of the dome, giving it great

dignity and richness of

effect.

FIG.

203.--EXTERIOR OF PANTH�ON,

PARIS.

The

dome, which is of stone throughout,

has three shells, the

intermediate shell

serving

to support the heavy stone

lantern. The architect was

Soufflot

(171381).

The

Grand

Th��tre, at

Bordeaux (1773, by Victor

Louis),

one of the largest and

finest

theatres in Europe, was

another product of this movement,

its stately

colonnade

forming one of the chief

ornaments of the city. Under Louis XVI.

there

was

a temporary reaction from this somewhat

pompous affectation of

antique

grandeur;

but there were few important

buildings erected during that unhappy

reign,

and

the reaction showed itself mainly in a

more delicate and graceful

style of interior

decoration.

It was reserved for the Empire to

set the seal of official

approval on the

Roman

Revival.

The

Arch of Triumph of the Carrousel, behind the

Tuileries, by Percier

and Fontaine,

the

magnificent Arc de l'�toile, at the

summit of the Avenue of the Champs

Elys�es,

by

Chalgrin; the wing

begun by Napoleon to connect the

Tuileries with the Louvre on

the

land side, and the church of the Madeleine, by

Vignon,

erected as a temple to the

heroes

of the Grande Arm�e, were all

designed, in accordance with the

expressed will

of

the Emperor himself, in a style as

Roman as the requirements of each

case would

permit.

All these monuments, begun

between 1806 and 1809, were completed

after

the

Restoration. The Arch

of the

Carrousel

is a

close copy of Roman models;

that of

the

�toile

(Fig.

204) was a much more original

design, of colossal dimensions.

Its

admirable

proportions, simple composition and

striking sculptures give it a

place

among

the noblest creations of its

class. The Madeleine

(Fig.

205), externally a

Roman

Corinthian temple of the largest

size, presents internally an

almost Byzantine

conception

with the three pendentive domes that

vault its vast nave, but all

the

details

are Roman. However suitable

for a pantheon or mausoleum, it

seems

strangely

inappropriate as a design for a Christian

church. To these monuments

should

be added the Bourse

or

Exchange, by Brongniart,

heavy in spite of its

Corinthian

peristyle, and the river front of the

Corps

L�gislatif or

Palais Bourbon, by

Poyet, the only

extant example of a dodecastyle

portico with a pediment. All of

these

designs

are characterized by great

elegance of detail and excellence of

execution, and

however

inappropriate in style to modern

uses, they add immensely to the

splendor

of

the French capital. Unquestionably no

feature can take the place

of a Greek or

Roman

colonnade as an embellishment for broad

avenues and open squares, or as

the

termination

of an architectural vista.

FIG.

204.--ARC DE L'�TOILE,

PARIS.

The

Greek revival took little hold of the

Parisian imagination. Its forms

were too

cold,

too precise and fixed, too

intractable to modern requirements to

appeal to the

French

taste. It counts but one

notable monument, the church of St.

Vincent de

Paul, by

Hittorff, who

sought to apply to this design the

principles of Greek

external

polychromy;

but the frescoes and ornaments failed to

withstand the Parisian

climate,

and

were finally erased. The N�o-Grec

movement already referred to,

initiated by

Duc,

Duban, and Labrouste about 1830, aimed

only to introduce into modern

design

the

spirit and refinement, the purity and

delicacy of Greek art, not its

forms (Fig.

206).

Its chief monuments were the

remodelling, by Duc, of the

Palais

de Justice,

of

which

the new west fa�ade is the most

striking single feature; the

beautiful Library

of

the �cole des Beaux-Arts, by

Duban; the

library of Ste.

Gen�vi�ve, by

Labrouste,

in

which a long fa�ade is treated without a

pilaster or column, simple arches

over a

massive

basement forming the dominant

motive, while in the interior a system

of

iron

construction with glazed domes

controls the design; and the

commemorative

Colonne

Juillet, by Duc, the

most elegant and appropriate of all

modern memorial

columns.

All these buildings, begun

between 1830 and 1850 and completed

at

various

dates, are distinguished by a

remarkable purity and freedom of

conception

and

detail, quite unfettered by the

artificial trammels of the official

academic style

then

prevalent.

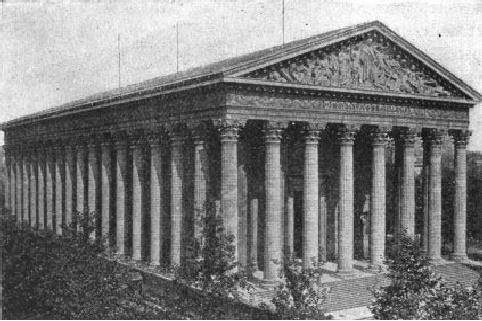

FIG.

205.--THE MADELEINE,

PARIS.

THE

CLASSIC REVIVAL ELSEWHERE.

The

other countries of Europe

have little to

show

in the way of imitations of classic

monuments or reproductions of

Roman

colonnades.

In Italy the church of S.

Francesco di Paola, at

Naples, in quasi-

imitation

of the Pantheon at Rome, with

wing-colonnades, and the Superga, at

Turin

(1706,

by Ivara); the

fa�ade of the San Carlo

Theatre, at Naples, and the

Braccio

Nuovo

of the Vatican (1817, by Stern)

are the monuments which come the

nearest to

the

spirit and style of the Roman

Revival. Yet in each of these

there is a large

element

of originality and freedom of treatment

which renders doubtful their

classification

as examples of that movement.

A

reflection of the Munich school is seen

in the modern public buildings of

Athens,

designed

in some cases by German

architects, and in others by native

Greeks. The

University,

the Museum buildings, the Academy of Art and

Science, and other

edifices

exemplify fairly successful efforts to

adapt the severe details of

classic Greek

art

to modern windowed structures. They

suffer somewhat from the too

liberal use of

stucco

in place of marble, and from the

conscious affectation of an extinct

style. But

they

are for the most part pleasing and

monumental designs, adding

greatly to the

beauty

of the modern city.

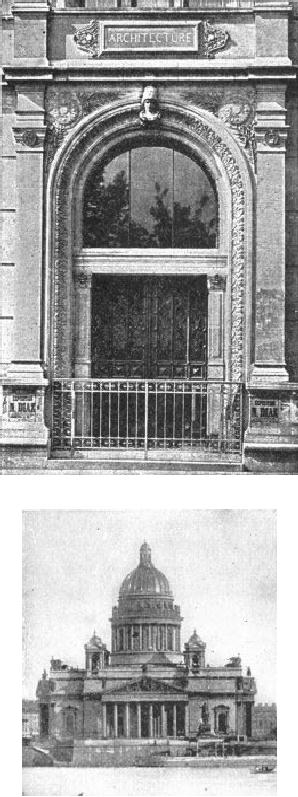

FIG.

206.--DOORWAY, �COLE DES BEAUX-ARTS,

PARIS.

FIG.

207.--ST. ISAAC'S CATHEDRAL,

ST. PETERSBURG.

In

Russia, during and after the

reign of Peter the Great (16891725),

there appeared

a

curious mixture of styles. A style

analogous to the Jesuit in Italy and

the

Churrigueresque

in Spain was generally

prevalent, but it was in many cases

modified

by

Muscovite traditions into nondescript

forms like those of the

Kremlin, at

Moscow,

or

the less extravagant Citadel

Church and Smolnoy Monastery at

St. Petersburg.

Along

with this heavy and barbarous style,

which prevails generally in the

numerous

palaces

of the capital, finished in stucco with

atrocious details, a more

severe and

classical

spirit is met with. The church of the Greek

Rite at

St. Petersburg

combines

a

Roman domical interior with an

exterior of the Greek Doric

order. The Church of

Our

Lady of Kazan has

a semicircular colonnade projecting from

its transept,

copying

as nearly as may be the colonnades in front of

St. Peter's. But the

greatest

classic

monument in Russia is the Cathedral

of St. Isaac (Fig.

207), at St.

Petersburg,

a vast rectangular edifice with four

Roman Corinthian

pedimental

colonnades

projecting from its faces, and a

dome with a peristyle crowning

the

whole.

Despite many defects of detail, and the

use of cast iron for the dome,

which

pretends

to be of marble, this is one of the most

impressive churches of its

size in

Europe.

Internally it displays the costliest

materials in extraordinary profusion,

while

externally

its noble colonnades go far to

redeem its bare attic and

the material of its

dome.

The Palace

of the Grand Duke

Michael, which

reproduces, with

improvements,

Gabriel's colonnades of the Garde

Meuble at Paris on its

garden

front,

is a nobly planned and commendable

design, agreeably contrasting with

the

debased

architecture of many of the public

buildings of the city. The Admiralty

with

its

Doric pilasters, and the New

Museum, by von

Klenze of Munich, in a skilfully

modified

Greek style, with effective

loggias, are the only other

monuments of the

classic

revival in Russia which can find

mention in a brief sketch

like this. Both

are

notable

and in many respects admirable buildings,

in part redeeming the vulgarity

which

is unfortunately so prevalent in the

architecture of St.

Petersburg.

The

MONUMENTS

of the

Classic Revival have been

referred to in the foregoing text

at

sufficient length to preclude the

necessity of further enumeration

here.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.