|

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL |

| << RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS |

| THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY >> |

CHAPTER

XXIV.

RENAISSANCE

ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN,

AND

PORTUGAL.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before,

Fergusson, Palustre Also, von

Bezold, Die

Baukunst

der

Renaissance in Deutschland, Holland,

Belgien und Dänemark (in

Hdbuch.

d.

Arch.).

Caveda (tr. Kugler),

Geschichte

der Baukunst in Spanien.

Fritsch, Denkmäler

der

deutschen Renaissance (plates).

Junghändel, Die

Baukunst Spaniens.

Lambert und

Stahl,

Motive

der deutschen Architektur.

Lübke, Geschichte

der Renaissance in

Deutschland.

Prentice, Renaissance

Architecture and Ornament in

Spain.

Uhde,

Baudenkmäler

in Spanien.

Verdier et Cattois, Architecture

civile et domestique.

Villa

Amil,

Hispania

Artistica y Monumental.

AUSTRIA;

BOHEMIA. The

earliest appearance of the Renaissance in

the architecture

of

the German states was in the

eastern provinces. Before the

close of the fifteenth

century

Florentine and Milanese architects

were employed in Austria,

Bohemia, and

the

Tyrol, where there are a number of

palaces and chapels in an unmixed

Italian

style.

The portal of the castle of

Mahrisch-Trübau dates from 1492; while to

the

early

years of the 16th century belong a

cruciform chapel at Gran, the remodelling

of

the

castle at Cracow, and the chapel of the

Jagellons in the same city--the

earliest

domical

structure of the German Renaissance,

though of Italian design. The Schloss

Porzia

(1510), at

Spital in Carinthia, is a fine

quadrangular palace, surrounding

a

court

with arcades on three sides, in which the

open stairs form a

picturesque

interruption

with their rampant arches. But for the

massiveness of the details it

might

be a Florentine palace. In addition to

this, the famous Arsenal

at

Wiener-

Neustadt

(1524), the portal of the Imperial Palace

(1552), and the Castle

Schalaburg

on the

Danube (15301601), are attributed to

Italian architects, to

whom

must also be ascribed a number of

important works at Prague.

Chief among

these

the Belvedere

(1536, by

Paolo

della Stella), a

rectangular building

surrounded

by

a graceful open arcade,

above which it rises with a second

story crowned by a

curved

roof; the Waldstein Palace (162129),

by Giov.

Marini, with

its imposing

loggia;

Schloss

Stern, built on the

plan of a six-pointed star (14591565)

and

embellished

by Italian artists with stucco

ornaments and frescoes; and parts of

the

palace

on the Hradschin, by Scamozzi,

attest the supremacy of Italian art in

Bohemia.

The

same is true of Styria, Carinthia, and

the Tyrol; e.g.

Schloss

Ambras at

Innsbrück

(1570).

GERMANY:

PERIODS. The

earliest manifestation of the Renaissance

in what is now

the

German Empire, appeared in the

works of painters like Dürer and

Burkmair, and

in

occasional buildings previous to 1525.

The real transformation of

German

architecture,

however, hardly began until after the

Peace of Augsburg, in 1555. From

that

time on its progress was

rapid, its achievements

being almost wholly in the

domain

of secular architecture--princely and

ducal castles, town halls or

Rathhäuser,

and

houses of wealthy burghers or

corporations. It is somewhat singular

that the

German

emperors should not have

undertaken the construction of a new

imperial

residence

on a worthy scale, the palaces of Munich and

Berlin being aggregations

of

buildings

of various dates about a

nucleus of mediæval origin, and with no

single

portion

to compare with the stately châteaux of

the French kings.

Church

architecture

was neglected, owing to the

Reformation, which turned to its own

uses

the

existing churches, while the Roman

Catholics were too

impoverished to replace

the

edifices they had lost.

The

periods of the German Renaissance

are less well marked than

those of the

French;

but its successive developments follow

the same general progression,

divided

into

three stages:

I.

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE, 15251600, in which the

orders were infrequently

used,

mainly

for porches and for gable decoration. The

conceptions and spirit of

most

monuments

were still strongly tinged

with Gothic feeling.

II.

THE LATE RENAISSANCE, 16001675,

characterized by a dry, heavy treatment,

in

which

too often neither the

fanciful gayety of the previous

period nor the simple and

monumental

dignity of classic design

appears. Broken curves,

large scrolls,

obelisks,

and

a style of flat relief carving

resembling the Elizabethan are

common. Occasional

monuments

exhibit a more correct and

classic treatment after Italian

models.

III.

THE DECLINE OR BAROQUE PERIOD,

16751800, employing the orders in a

style of

composition

oscillating between the extremes of

bareness and of Rococo

over-

decoration.

The ornament partakes of the character of

the Louis XV. and Italian

Jesuit

styles, being most

successful in interior decoration, but

externally running to

the

extreme of unrestrained fancy.

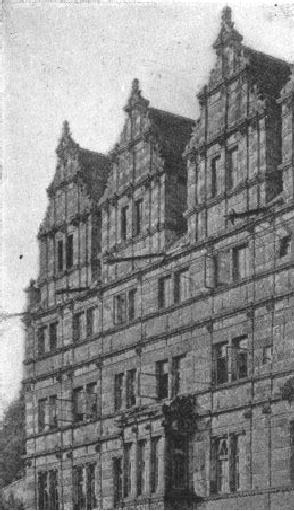

CHARACTERISTICS.

In

none of these periods do we

meet with the sober,

monumental

treatment of the Florentine or Roman

schools. A love of

picturesque

variety

in masses and sky-lines, inherited from

mediæval times, appears in the

high

roofs,

stepped gables and lofty dormers which

are universal. The roofs

often

comprise

several stories, and are

lighted by lofty gables at either

end, and by

dormers

carried up from the side walls through

two or three stories. Gables

and

dormers

alike are built in diminishing

stages, each step adorned

with a console or

scroll,

and the whole treated with pilasters or

colonnettes and entablatures

breaking

over

each support (Fig. 191).

These roofs, dormers, and

gables contribute the

most

noticeable

element to the general effect of

most German Renaissance

buildings, and

are

commonly the best-designed features in

them. The orders are scantily

used and

usually

treated with utter disregard of classic

canons, being generally far

too massive

and

overloaded with ornament. Oriels,

bay-windows, and turrets, starting

from

corbels

or colonnettes, or rarely from the

ground, diversify the façade, and

spires of

curious

bulbous patterns give added

piquancy to the picturesque sky-line. The

plans

seldom

had the monumental symmetry and largeness

of Italian and French models;

courtyards

were often irregular in

shape and diversified with balconies and

spiral

staircase-turrets.

The national leaning was

always toward the quaint and fantastic,

as

well

in the decoration as in the composition.

Grotesques, caryatids, gaînes

(half-

figures

terminating below in sheath-like

supports), fanciful rustication, and

many

other

details give a touch of the Baroque

even to works of early date.

The same

principles

were applied with better

success to interior decoration,

especially in the

large

halls of the castles and town-halls, and

many of their ceilings were

sumptuous

and

well-considered designs, deeply

panelled, painted and gilded in

wood or plaster.

FIG.

191.--SCHLOSS HÄMELSCHENBURG.

CASTLES.

The

Schloss

or

Burg

of the

German prince or duke

retained throughout the

Renaissance

many mediæval characteristics in plan and

aspect. A large proportion

of

these

noble residences were built upon

foundations of demolished feudal

castles,

reproducing

in a new dress the ancient round towers

and vaulted guard-rooms and

halls,

as in the Hartenfels at Torgau, the

Heldburg (both in Saxony), and the

castle of

Trausnitz,

in Bavaria, among many others. The

Castle

at

Torgau

(1540) is

one of the

most

imposing of its class, with

massive round and square towers

showing externally,

and

court façades full of picturesque

irregularities. In the great Castle

at

Dresden

the

plan

is more symmetrical, and the Renaissance

appears more distinctly in the

details

of

the Georgenflügel (153050), though at that early

date the classic orders

were

almost

ignored. The portal of the Heldburg,

however, built in 1562, is a

composition

quite

in the contemporary French vein, with

superposed orders and a

crowning

pediment

over a massive

basement.

Another

important series of castles or

palaces are of more regular

design, in which

the

feudal traditions tend to disappear. The

majority belong to the end of the

16th

and

beginning of the 17th centuries. They are

built around large rectangular

courts

with

arcades in two or three stories on

one or more sides, but

rarely surrounding it

entirely.

In these the segmental arch is

more common than the semicircular,

and

springs

usually from short and stumpy Ionic or

Corinthian columns. The rooms

and

halls

are arranged en

suite, without

corridors, and a large and lofty banquet

hall

forms

the dominant feature of the series. The

earliest of these regularly

planned

palaces

are of Italian design. Chief

among them is the Residenz

at

Landshut

(1536

43),

with a thoroughly Roman plan, by pupils

of Giulio Romano, and exterior

and

court

façades of great dignity

treated with the orders. More German in

its details,

but

equally interesting, is the Fürstenhof

at

Wismar, in

brick and terra-cotta, by

Valentino

di Lira and

Van

Aken (1553); while

in the Piastenschloss

at

Brieg (1547

72),

by Italian architects, the treatment in

parts suggests the richest

works of the

style

of Francis I. In other castles the

segmental arch and stumpy columns or

piers

show

the German taste, as in the Plassenburg, by

Kaspar

Vischer (155464),

the

castle

at Plagnitz, and the Old

Castle at

Stuttgart, all

dating from about 155055.

Heidelberg

Castle, in

spite of its mediæval aspect

from the river and its

irregular

plan,

ranks as the highest achievement of the

German Renaissance in palace

design.

The

most interesting parts among

its various wings built at

different dates--the

earlier

portions still Gothic in

design--are the Otto

Heinrichsbau (1554) and

the

Friedrichsbau

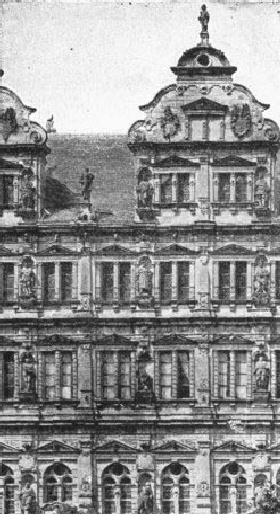

(1601). The

first of these appears

somewhat simpler in its

lines than

the

second, by reason of having

lost its original

dormer-gables. The orders,

freely

treated,

are superposed in three

stories, and twin windows, niches,

statues, gaînes,

medallions

and profuse carving produce an

effect of great gayety and

richness. The

Friedrichsbau

(Fig. 192), less quiet in

its lines, and with high

scroll-gabled and

stepped

dormers, is on the other hand more

soberly decorated and

more

somewhat

the same spirit, but with even

greater simplicity of

detail.

TOWN

HALLS. These

constitute the most interesting

class of Renaissance

buildings

in

Germany, presenting a considerable

variety of types, but nearly all built in

solid

blocks

without courts, and adorned with towers

or spires. A high roof crowns

the

building,

broken by one or more high

gables or many-storied dormers. The

majority

of

these town halls present

façades much diversified by projecting

wings, as at Lemgo

and

Paderborn, or by oriels and turrets, as

at Altenburg

(156264);

and the towers

which

dominate the whole terminate usually in

bell-shaped cupolas, or in

more

capricious

forms with successive swellings and

contractions, as at Dantzic

(1587).

A

few, however, are designed with

monumental simplicity of mass; of

these that at

Bremen

(1612) is

perhaps the finest, with its

beautiful exterior arcade on

strong

Doric

columns. The town hall of Nuremberg is

one of the few with a court, and

presents

a façade of almost Roman

simplicity (161319); that at Augsburg

(1615)

is

equally

classic and more pleasing; while at

Schweinfurt, Rothenburg (1572),

Mülhausen,

etc., are others worthy of

mention.

FIG.

192.--THE FRIEDRICHSBAU,

HEIDELBERG.

CHURCHES.

St. Michael's, at Munich,

is almost the only important church of

the

first

period in Germany (1582), but it is worthy to rank

with many of the most

notable

contemporary Italian churches. A wide

nave covered by a majestic

barrel

vault,

is flanked by side chapels,

separated from each other by

massive piers and

forming

a series of gallery bays

above. There are short

transepts and a choir, all in

excellent

proportion and treated with details

which, if somewhat heavy, are

appropriate

and reasonably correct. The Marienkirche

at

Wolfenbüttel (1608) is a

fair

sample of the parish churches of the

second period. In the exterior of this

church

pointed

arches and semi-Gothic tracery

are curiously associated with

heavy rococo

carving.

The simple rectangular mass,

square tower, and portal with massive

orders

and

carving are characteristic

features. Many of the church-towers are

well

proportioned

and graceful structures in spite of the

fantastic outlines of their

spires.

One

of the best and purest in style is that

of the University Church at

Würzburg

(15871600).

HOUSES.

Many of the

German houses of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries

would

merit extended notice in a

larger work, as among the most

interesting lesser

monuments

of the Renaissance. Nuremberg and

Hildesheim are particularly rich

in

such

houses, built either for private

citizens or for guilds and corporations.

Not a few

of

the half-timbered houses of the time

are genuine works of art, though

interest

chiefly

centres in the more monumental

dwellings of stone. In this

domestic

architecture

the picturesque quality of German design

appears to better

advantage

than

in more monumental edifices, and

their broadly stepped

gables, corbelled

oriels,

florid

portals and want of formal symmetry

imparting a peculiar and

undeniable

charm.

The Kaiserhaus and Wedekindsches Haus at

Hildesheim; Fürstenhaus

at

Leipzig;

Peller, Hirschvogel, and Funk houses at

Nuremberg; the Salt House

at

Frankfurt,

and Ritter House at Heidelberg,

are a few of the most noted

among these

examples

of domestic architecture.

FIG.

193.--ZWINGER PALACE,

DRESDEN.

LATER

MONUMENTS. The

Zwinger

Palace at

Dresden (Fig. 193), is the

most

elaborate

and wayward example of the German palace

architecture of the third

period.

Its details are of the most

exaggerated rococo type,

like confectioner's work

done

in stone; and yet the building has an

air of princely splendor which

partly

atones

for its details. Besides this

palace, Dresden possesses in the

domical

Marienkirche

(Fig.

194) a very meritorious example of late

design. The proportions

are

good, and the detail, if not interesting,

is at least inoffensive, while the whole

is

a

dignified and rational piece of work. At

Vienna are a number of palaces of the

third

period,

more interesting for their beautiful

grounds and parks than for

intrinsic

architectural

merit. As in Italy, this was the period

of stucco, and although in

Vienna

this

cheap and perishable material

was cleverly handled, and the

ornament produced

was

often quaint and effective, the results

lack the permanence and dignity of

true

building

in stone or brick, and may be dismissed

without further mention.

FIG.

194.--CHURCH OF ST. MARY (MARIENKIRCHE),

DRESDEN.

In

minor works the Germans were far

less prolific than the Italians or

Spaniards. Few

of

their tombs were of the first

importance, though one, the Sebald

Shrine,

in

Nuremberg,

by Peter

Vischer (150619),

is a splendid work in bronze, in

the

transitional

style; a richly decorated canopy on

slender metal colonnettes

covering

and

enclosing the sarcophagus of the saint.

There are a large number of

fountains in

the

squares of German and Swiss

cities which display a high order of

design, and are

among

the most characteristic minor products of

German art.

SPAIN.

The

flamboyant Gothic style

sufficed for a while to meet the

requirements of

the

arrogant and luxurious period which in

Spain followed the overthrow of

the

Moors

and the discovery of America. But it was

inevitable that the Renaissance

should

in time make its influence

felt in the arts of the Iberian

peninsula, largely

through

the employment of Flemish artists. In

jewelry and silverwork, arts

which

received

a great impulse from the importation of

the precious metals from the New

World,

the forms of the Renaissance found

special acceptance, so that the new

style

received

the name of the Plateresque

(from

platero,

silversmith). This was a not

inept

name

for the minutely detailed and sumptuous

decoration of the early

Renaissance,

which

lasted from 1500 to the accession of

Philip II. in 1556. It was

characterized

by

surface-decoration spreading over

broad areas, especially

around doors and

windows,

florid escutcheons and Gothic

details mingling with delicately

chiselled

arabesques.

Decorative pilasters with broken

entablatures and carved

baluster-shafts

were

employed with little reference to

constructive lines, but with great

refinement of

detail,

in spite of the exuberant profusion of

the ornament.

To

this style, after the artistic

inaction of Philip II.'s reign,

succeeded the coldly

classic

style practised by Berruguete

and

Herrera, and

called the Griego-Romano.

In

spite

of the attempt to produce works of

classical purity, the buildings of this

period

are

for the most part singularly devoid of

originality and interest. This

style lasted

until

the middle of the seventeenth century, and in the

case of certain works

and

artists,

until its close. It was

followed, at least in ecclesiastical

architecture, by the

so-called

Churrigueresque, a

name derived from an otherwise

insignificant architect,

Churriguera, who

like Maderna and Borromini in Italy,

discarded all the proprieties

of

architecture, and rejoiced in the wildest

extravagances of an untrained fancy

and

debased

taste.

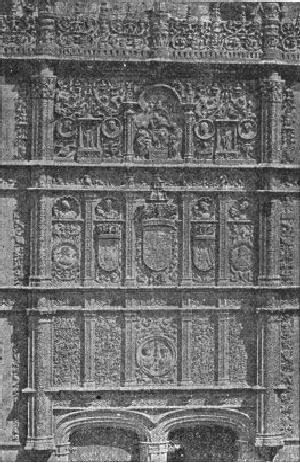

FIG.

195.--DOOR OF THE UNIVERSITY,

SALAMANCA.

EARLY

MONUMENTS. The

earliest ecclesiastical works of the

Renaissance period,

like

the cathedrals of Salamanca, Toledo, and

Segovia, were almost purely

Gothic in

style.

Not until 1525 did the new forms begin to

dominate in cathedral design.

The

cathedral

at Jaen, by

Valdelvira

(1525), an

imposing structure with three

aisles and

side

chapels, was treated

internally with the Corinthian order

throughout. The

Cathedral

of Granada

(1529, by

Diego

de Siloe) is

especially interesting for its

great

domical

sanctuary 70 feet in diameter, and for

the largeness and dignity of

its

conception

and details. The cathedral of Malaga, the

church of San Domingo at

Salamanca,

and the monastery of San Girolamo in the

same city are either wholly

or

in

part Plateresque, and provided with

portals of especial richness of

decoration.

Indeed,

the portal of S. Domingo practically

forms the whole façade.

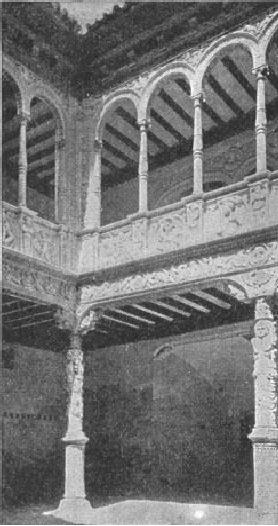

FIG.

196.--CASA DE ZAPORTA:

COURTYARD.

In

secular architecture the Hospital

of

Santa

Cruz at

Toledo, by Enrique

de Egaz

(150416),

is one of the earliest examples of the

style. Here, as also in

the

University

at

Salamanca

(Fig.

195), the portal is the most notable

feature,

suggesting

both Italian and French models in its

details. The great College

at

Alcala

de

Heñares is

another important early monument of the

Renaissance (150017, by

Pedro

Gumiel). In

most designs the preference

was for long façades of

moderate

height,

with a basement showing few openings, and

a bel

étage lighted

by large

windows

widely spaced. Ornament was

chiefly concentrated about the

doors and

windows,

except for the roof balustrades, which

were often exceedingly

elaborate.

Occasionally

a decorative motive is spread

over the whole façade, as in the

Casa

de

las

Conchas at

Salamanca, adorned with cockle-shells

carved at intervals all over

the

front--a

bold and effective device; or the

Infantada palace with its

spangling of

carved

diamonds. The courtyard or patio

was

an indispensable feature of

these

buildings,

as in all hot countries, and was

surrounded by arcades frequently of

the

most

fanciful design overloaded with minute

ornament, as in the Infantado

at

Guadalajara,

the Casa

de Zaporta,

formerly at Saragossa (now removed to

Paris; Fig.

196),

and the Lupiana monastery. The patios in

the Archbishop's

Palace at

Alcala de

Heñares

and the Collegio

de los Irlandeses at

Salamanca are of simpler

design; that

of

the Casa

de Pilatos at

Seville is almost purely Moorish.

Salamanca abounds in

buildings

of this period.

THE

GRIEGO-ROMANO. The

more classic treatment of

architectural designs by the

use

of the orders was introduced by

Alonzo

Berruguete (14801560?),

who studied

in

Italy after 1503. The Archbishop's Palace

and the Doric Gate

of

San

Martino,

both

at Toledo, were his work, as well as the

first palace at Madrid. The Palladio

of

Spain

was, however, by Juan

de Herrera (died

1597), the architect of Valladolid

Cathedral, built under

Philip V. This vast edifice

follows the general lines of

the

earlier

cathedrals of Jaen and Granada, but in a

style of classical correctness

almost

severe

in aspect, but well suited to the grand

scale of the church. The masterpiece

of

this

period was the monastery of the

Escurial,

begun by Juan

Battista of

Toledo, in

1563,

but not completed until nearly one

hundred and fifty years later. Its

final

architectural

aspect was largely due to

Herrera. It is a vast rectangle of 740 ×

580

feet,

comprising a complex of courts,

halls, and cells, dominated by the

huge mass of

the

chapel. This last is an

imposing domical church covering 70,000

square feet,

treated

throughout with the Doric order, and

showing externally a lofty dome

and

campaniles

with domical lanterns, which serve to

diversify the otherwise

monotonous

mass

of the monastery. What the Escurial lacks

in grace or splendor is at least in

a

measure

redeemed by its majestic

scale and varied sky-lines. The

Palace

of

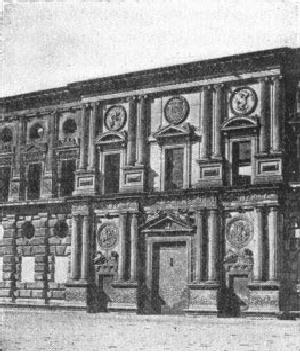

Charles

V. (Fig.

197), adjoining the Alhambra at Granada,

though begun as early as

1527

by Machuca,

was mainly due to Berruguete, and is an

excellent example of the

Spanish

Palladian style. With its

circular court, admirable

proportions and well-

studied

details, this often maligned

edifice deserves to be ranked

among the most

successful

examples of the style. During this

period the cathedral of Seville

received

many

alterations, and the upper part of the

adjoining Moorish tower of the

Giralda,

burned

in 1395, was rebuilt by Fernando

Ruiz in the

prevalent style, and with

considerable

elegance and appropriateness of

design.

Of

the Palace

at

Madrid,

rebuilt by Philip V. after the

burning of the earlier palace

in

1734,

and mainly the work of an Italian, Ivara; the

Aranjuez palace (1739, by

Francisco

Herrera), and the

Palace at San

Ildefonso, it

need only be said that their

chief

merit lies in their size and

the absence of those glaring

violations of good

taste

which

generally characterized the successors of

Churriguera. In ecclesiastical

design

these

violations of taste were

particularly abundant and excessive,

especially in the

façades

and in the sanctuary--huge aggregations of

misplaced and vulgar detail,

with

hardly

an unbroken pediment, column, or arch in

the whole. Some extreme

examples

of

this abominable style are to be found in

the Spanish-American churches of

the

17th

and 18th centuries, as at Chihuahua

(Mexico), Tucson (Arizona), and

other

places.

The least offensive features of the

churches of this period were the

towers,

usually

in pairs at the west end,

some of them showing excellent

proportions and

good

composition in spite of their

execrable details.

FIG.

197.--PALACE OF CHARLES V.,

GRANADA.

Minor

architectural works, such as the

rood screens in the churches of

Astorga and

Medina

de Rio Seco, and many tombs at

Granada, Avila, Alcala,

etc., give evidence

of

superior skill in decorative

design, where constructive

considerations did not limit

the

exercise of the imagination.

PORTUGAL.

The

Renaissance appears to have

produced few notable works

in

Portugal.

Among the chief of these are

the Tower, the

church, and the Cloister,

at

Belem.

These display a riotous

profusion of minute carved ornament, with

a free

commingling

of late Gothic details,

wearisome in the end in spite of the

beauty of its

execution

(150040?). The church of Santa

Cruz at

Coimbra, and that of Luz,

near

Lisbon,

are among the most noted of

the religious monuments of the

Renaissance,

while

in secular architecture the royal

palace at Mafra

is worthy of

mention.

MONUMENTS.

(Mainly

supplementary to preceding text.)

AUSTRIA, BOHEMIA,

etc.: At

Prague,

Schloss Stern, 14591565;

Schwarzenburg Palace, 1544; Waldstein

Palace,

1629;

Salvator Chapel, Vienna, 1515;

Schloss Schalaburg, near Mölk,

15301601;

Standehaus,

Gratz, 1625. At Vienna: Imperial

palace, various dates;

Schwarzenburg and

Lichtenstein

palaces, 18th century.

GERMANY, FIRST PERIOD: Schloss Baden, 151029

and part 156982; Schloss

Merseburg,

1514,

with late 16th-century portals;

Fuggerhaus at Augsburg, 1516; castles

of

Neuenstein,

153064; Celle, 153246 (and

enlarged, 166570); Dessau,

1533;

Leignitz,

portal, 1533; Plagnitz, 1550; Schloss

Gottesau, 155388; castle of

Güstrow,

155565;

of Oels, 15591616; of Bernburg, 1565; of

Heiligenburg, 156987; Münzhof

at

Munich, 1575; Lusthaus (demolished) at

Stuttgart, 1575; Wilhelmsburg Castle

at

Schmalkald,

158490; castle of Hämelschenburg,

15881612.--SECOND PERIOD:

Zunfthaus

at Basle, 1578, in advanced style; so

also Juleum at Helmstädt,

15931612;

gymnasium

at Brunswick, 15921613; Spiesshof at

Basle, 1600; castle at Berlin,

1600

1616,

demolished in great part;

castle Bevern, 1603; Dantzic,

Zeughaus, 1605;

Wallfahrtskirche

at Dettelbach, 1613; castle

Aschaffenburg, 160513;

Schloss

Weikersheim,

160083.--THIRD PERIOD:

Zeughaus at Berlin, 1695; palace at

Berlin by

Schlüter,

16991706; Catholic church, Dresden.

(For Classic Revival, see

next

chapter.)--TOWN HALLS: At Heilbronn, 1535; Görlitz, 1537;

Posen, 1550; Mülhausen,

1552;

Cologne, porch with Corinthian

columns and Gothic arches,

1569; Lübeck

(Rathhaushalle),

1570; Schweinfurt, 1570; Gotha, 1574;

Emden, 157476; Lemgo,

1589;

Neisse, 1604; Nordhausen, 1610;

Paderborn, 161216; Gernsbach,

1617.

SPAIN,

16TH CENTURY:

Monastery San Marcos at

Leon; palace of the Infanta,

Saragossa;

Carcel

del Corte at Baez; Cath. of

Malaga, W. front, 1538, by de Siloë;

Tavera Hospital,

Toledo,

1541, by de Bustamente; Alcazar at

Toledo, 1548; Lonja (Town

Hall) at

Saragossa,

1551; Casa de la Sal, Casa

Monterey, and Collegio de

los Irlandeses, all

at

Salamanca;

Town Hall, Casa de los

Taveras and upper part of

Giralda, all at

Seville.--

17TH CENTURY:

Cathedral del Pilar,

Saragossa, 1677; Tower del

Seo, 1685.--18TH

CENTURY:

palace at Madrid, 1735; at Aranjuez,

1739; cathedral of Santiago, 1738;

Lonja

at Barcelona, 1772.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.