|

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS |

| << RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES |

| RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL >> |

CHAPTER

XXIII.

RENAISSANCE

ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND

THE

NETHERLANDS.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before,

Fergusson, Palustre. Also,

Belcher and

Macartney,

Later

Renaissance Architecture in

England.

Billings, Baronial

and Ecclesiastical

Antiquities

of Scotland.

Blomfield, A

Short History of Renaissance

Architecture in

England.

Britton, Architectural

Antiquities of Great

Britain.

Ewerbeck, Die

Renaissance

in

Belgien und Holland.

Galland, Geschichte

der Hollandischen Baukunst im

Zeitalter

der

Renaissance.

Gotch and Brown, Architecture

of the Renaissance in

England.

Loftie,

Inigo

Jones and Wren.

Nash, Mansions

of England.

Papworth, Renaissance

and Italian

Styles

of Architecture in Great

Britain.

Richardson, Architectural

Remains of the

Reigns

of

Elizabeth and James I. Schayes,

Histoire

de l'architecture en Belgique.

THE

TRANSITION. The

architectural activity of the sixteenth

century in England

was

chiefly devoted to the erection of

vast country mansions for the nobility

and

wealthy

bourgeoisie. In

these seignorial residences a

degenerate form of the Gothic,

known

as the Tudor style, was employed

during the reigns of Henry VII. and

Henry

VIII.,

and they still retained much of the

feudal aspect of the Middle Ages.

This style,

with

its broad, square windows and

ample halls, was well suited

to domestic

architecture,

as well as to collegiate buildings, of which a

considerable number were

erected

at this time. Among the more

important palaces and manor-houses of

this

period

are the earlier parts of Hampton

Court, Haddon and Hengreave

Halls, and the

now

ruined castles of Raglan and

Wolterton.

ELIZABETHAN

STYLE. Under

Elizabeth (15581603) the progress of

classic

culture

and the employment of Dutch and Italian artists

led to a gradual

introduction

of

Renaissance forms, which, as in France,

were at first mingled with

others of

Gothic

origin. Among the foreign

artists in England were the

versatile Holbein,

Trevigi

and Torregiano from Italy, and Theodore

Have, Bernard Jansen, and

Gerard

Chrismas

from Holland. The pointed arch

disappeared, and the orders began to

be

used

as subordinate features in the decoration

of doors, windows, chimneys,

and

mantels.

Open-work balustrades replaced

externally the heavy Tudor

battlements,

and

a peculiar style of carving in flat

relief-patterns, resembling appliqu�

designs

cut

out

with the jigsaw and attached by nails or

rivets, was applied with little

judgment

to

all possible features. Ceilings

were commonly finished in

plaster, with elaborate

interlacing

patterns in low relief; and this, with

the increasing use of

interior

woodwork,

gave to the mansions of this time a

more homelike but less

monumental

aspect

internally. English architects, like

Smithson and Thorpe, now began to win

the

patronage

at first monopolized by foreigners. In

Wollaton

Hall (1580), by

Smithson,

the

orders were used for the main

composition with mullioned windows, much

after

the

fashion of Longleat

House,

completed a year earlier by

his master, John of

Padua.

During the following period, however

(15901610), there was a

reaction

toward

the Tudor practice, and the orders were

again relegated to subordinate

uses.

Of

their more monumental

employment, the Gate

of Honor of

Caius College,

Cambridge,

is one of the earliest examples.

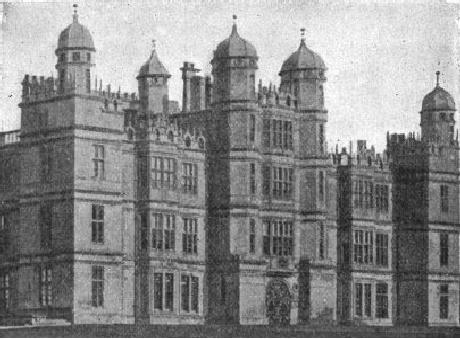

Hardwicke and Charlton Halls,

and

Burghley,

Hatfield, and Holland Houses (Fig. 184),

are noteworthy monuments of

the

style.

FIG.

184.--BURGHLEY HOUSE.

JACOBEAN

STYLE. During the

reign of James I. (160325), details

of classic origin

came

into more general use, but

caricatured almost beyond

recognition. The orders,

though

much employed, were treated without

correctness or grace, and the

ornament

was

unmeaning and heavy. It is not worth while to dwell further upon

this style,

which

produced no important public

buildings, and soon gave way to a

more rigid

classicism.

CLASSIC

PERIOD. If the

classic style was late in

its appearance in England,

its final

sway

was complete and long-lasting. It

was Inigo

Jones (15721652)

who first

introduced

the correct and monumental style of the

Italian masters of classic

design.

For

Palladio, indeed, he seems to

have entertained a sort of

veneration, and the villa

which

he designed at Chiswick was a

reduced copy of Palladio's

Villa Capra, near

Vicenza.

This and other works of his

show a failure to appreciate the

unsuitability of

Italian

conceptions to the climate and tastes of

Great Britain; his efforts

to popularize

Palladian

architecture, without the resources which

Palladio controlled in the way of

decorative

sculpture and painting, were

consequently not always happy in

their

results.

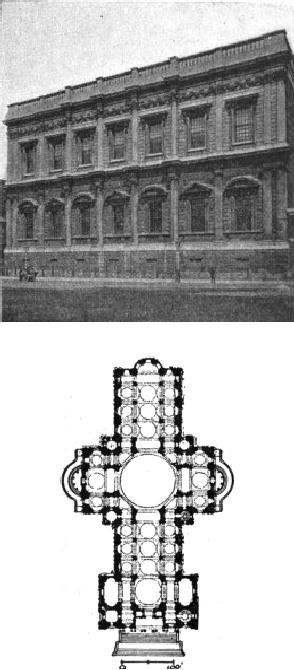

His greatest work was the design for a

new Palace

at Whitehall,

London. Of

this

colossal scheme, which, if completed,

would have ranked as the grandest

palace

of

the time, only the Banqueting

Hall (now

used as a museum) was ever

built (Fig.

185).

It is an effective composition in two

stories, rusticated throughout and

adorned

with

columns and pilasters, and contains a

fine vaulted hall in three

aisles. The plan

of

the palace, which was to have

measured 1,152 � 720 feet, was

excellent, largely

conceived

and carefully studied in its

details, but it was wholly beyond the

resources

of

the kingdom. The garden-front of

Somerset

House (1632;

demolished) had the

same

qualities of simplicity and dignity,

recalling the works of Sammichele.

Wilton

House,

Coleshill, the Villa at Chiswick, and

St. Paul's, Covent Garden,

are the best

known

of his works, showing him to

have been a designer of

ability, but hardly of

the

consummate genius which his

admirers attribute to him.

FIG.

185.--BANQUETING HALL,

WHITEHALL.

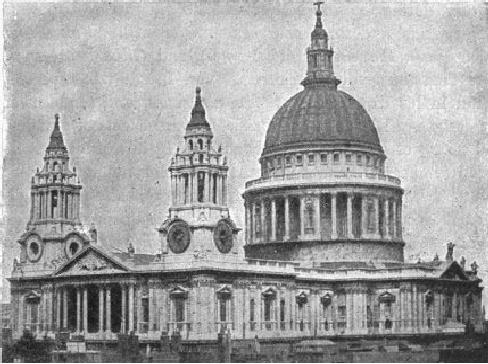

FIG.

186.--PLAN OF ST. PAUL'S,

LONDON.

ST.

PAUL'S CATHEDRAL. The

greatest of Jones's successors

was Sir

Christopher

Wren

(16321723),

principally known as the architect of

St.

Paul's Cathedral,

London,

built to replace the earlier Gothic

cathedral destroyed in the great

fire of

1666.

It was begun in 1675, and its

designer had the rare good fortune to

witness

its

completion in 1710. The plan, as finally adopted,

retained the general

proportions

of an English Gothic church,

measuring 480 feet in length,

with

transepts

250 feet long, and a grand

rotunda 108 feet in diameter at the

crossing

(Fig.

186). The style was strictly

Italian, treated with sobriety and

dignity, if

somewhat

lacking in variety and inspiration.

Externally two stories of the

Corinthian

order

appear, the upper story

being merely a screen to

hide the clearstory and

its

buttresses.

This is an architectural deception, not

atoned for by any special beauty

of

detail.

The dominant feature of the design is the

dome over the central area.

It

consists

of an inner shell, reaching a height of

216 feet, above which rises

the

exterior

dome of wood, surmounted by a

stone lantern, the summit of which is

360

feet

from the pavement (Fig. 187).

FIG.

187.--EXTERIOR OF ST. PAUL'S

CATHEDRAL.

This

exterior dome, springing from a high drum

surrounded by a magnificent

peristyle,

gives to the otherwise commonplace

exterior of the cathedral a

signal

majesty

of effect. Next to the dome the most

successful part of the design is the

west

front,

with its two-storied porch and

flanking bell-turrets. Internally the

excessive

relative

length, especially that of the choir,

detracts from the effect of the dome,

and

the

poverty of detail gives the whole a

somewhat bare aspect. It is

intended to relieve

this

ultimately by a systematic use of

mosaic decoration, especially in the

dome. The

central

area itself, in spite of the awkward

treatment of the four smaller arches of

the

eight

which support the dome, is a noble

design, occupying the whole width of

the

three

aisles, like the Octagon at Ely, and

producing a striking effect of

amplitude and

grandeur.

The dome above it is constructively

interesting from the employment of

a

cone

of brick masonry to support the

stone lantern which rises

above the exterior

wooden

shell. The lower part of the cone

forms the drum of the inner dome,

its

contraction

upward being intended to produce a

perspective illusion of

increased

height.

St.

Paul's ranks among the five

or six greatest domical

buildings of Europe, and is the

most

imposing modern edifice in

England.

WREN'S

OTHER WORKS. Wren

was conspicuously successful in the

designing of

parish

churches in London. St.

Stephen's,

Walbrook, is the most admired of

these,

with

a dome resting on eight

columns. Wren may be called the

inventor of the

English

Renaissance type of steeple, in which a

conical or pyramidal spire

is

harmoniously

added to a belfry on a square

tower with classic details. The

steeple of

Bow

Church,

Cheapside, is the most successful

example of the type. In

secular

architecture

Wren's most important works

were the plan for rebuilding London

after

the

Great Fire; the new courtyard of Hampton

Court, a quiet and

dignified

composition

in brick and stone; the pavilions and

colonnade of Greenwich

Hospital;

the

Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford, and the Trinity

College Library at

Cambridge.

Without

profound originality, these

works testify to the sound

good taste and

intelligence

of their designer.

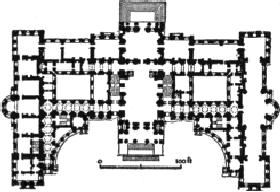

FIG.

188.--PLAN OF BLENHEIM.

THE

18TH CENTURY. The

Anglo-Italian style as used by

Jones and Wren

continued

in

use through the eighteenth century,

during the first half of which a number

of

important

country-seats and some churches

were erected. Van

Brugh (16661726),

Hawksmoor

(16661736),

and Gibbs

(16831751)

were then the leading

architects.

Van

Brugh was especially skilful in

his dispositions of plan and mass, and

produced

in

the designs of Blenheim and Castle Howard

effects of grandeur and variety

of

perspective

hardly equalled by any of his

contemporaries in France or Italy.

Blenheim, with

its monumental plan and the sweeping

curves of its front (Fig.

188),

has

an unusually palatial aspect, though the

striving for picturesqueness is

carried

too

far. Castle Howard is simpler, depending

largely for effect on a

somewhat

inappropriate

dome. To Hawksmoor, his pupil,

are due St.

Mary's, Woolnoth

(1715),

at London, in which by a bold rustication

of the whole exterior and by

windows

set in large recessed arches

he was enabled to dispense wholly with

the

orders;

St. George's, Bloomsbury; the new

quadrangle of All Souls at Oxford,

and

some

minor works. The two most noted

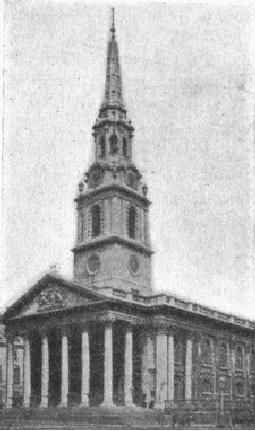

designs of James Gibbs are

St.

Martin's-in-

the-Fields, at

London (1726), and the Radcliffe

Library, at Oxford

(1747). In the

former

the use of a Corinthian portico--a

practically uncalled-for but

decorative

appendage--and

of a steeple mounted on the roof, with no

visible lines of

support

from

the ground, are open to

criticism. But the excellence of the

proportions, and the

dignity

and appropriateness of the composition, both

internally and externally, go far

to

redeem these defects (Fig.

189). The Radcliffe Library is a circular

domical hall

surrounded

by a lower circuit of alcoves and

rooms, the whole treated with

straightforward

simplicity and excellent proportions.

Colin Campbell, Flitcroft,

Kent

and

Wood, contemporaries of Gibbs, may be

dismissed with passing

mention.

FIG.

189.--ST. MARTIN'S-IN-THE-FIELDS,

LONDON.

Sir

William Chambers (172696)

was the greatest of the later

18th-century

architects.

His fame rests chiefly on

his Treatise

on Civil Architecture, and

the

extension

and remodelling of Somerset

House, in which he

retained the general

ordonnance

of

Inigo Jones's design,

adapting it to a frontage of some 600

feet. Robert

Adams, the

designer of Keddlestone Hall, Robert

Taylor (171488),

the architect of

the

Bank of England, and George

Dance, who

designed the Mansion House

and

Newgate

Prison, at London--the latter a vigorous

and appropriate composition

without

the orders--close the list of noted

architects of the eighteenth century. It

was

a

period singularly wanting in

artistic creativeness and spontaneity;

its productions

were

nearly all dull and respectable, or at

best dignified, but without

charm.

BELGIUM.

As in all

other countries where the

late Gothic style had been

highly

developed,

Belgium was slow to accept

the principles of the Renaissance in art.

Long

after

the dawn of the sixteenth century the Flemish

architects continued to

employ

their

highly florid Gothic alike for

churches and town-halls, with which they

chiefly

had

to do. The earliest Renaissance

buildings date from 153040, among

them being

the

H�tel du Saumon, at Malines, at Bruges

the Ancien Greffe, by Jean

Wallot, and

at

Li�ge

the Archbishop's

Palace, by

Borset. The

last named, in the singular

and

capricious

form of the arches and baluster-like

columns of its court,

reveals the taste

of

the age for what was outr�

and

odd; a taste partly due, no

doubt, to Spanish

influences,

as Belgium was in reality from 1506 to

1712 a Spanish province, and

there

was more or less interchange

of artists between the two countries. The

H�tel

de

Ville, at Antwerp,

by Cornelius

de Vriendt or

Floris

(151875),

erected in 1565,

is

the most important monument of the

Renaissance in Belgium. Its fa�ade, 305

feet

long

and 102 feet high, in four stories, is an

impressive creation in spite of

its

somewhat

monotonous fenestration and the

inartistic repetition in the third story

of

the

composition and proportions of the

second. The basement story

forms an open

arcade,

and an open colonnade or loggia runs

along under the roof, thus imparting

to

the

composition a considerable play of light and

shade, enhanced by the

picturesque

central

pavilion which rises to a height of

six stories in diminishing

stages. The style

is

almost Palladian in its

severity, but in general the Flemish

architects disdained the

restrictions

of classic canons, preferring a

more florid and fanciful

effect than could

be

obtained by mere combinations of

Roman columns, arches, and

entablatures. De

Vriendt's

other works were mostly

designs for altars, tabernacles and the

like; among

them

the rood screen in Tournay Cathedral. His

influence may be traced in the

H�tel

de

Ville at Flushing (1594).

FIG.

190.--RENAISSANCE HOUSES,

BRUSSELS.

The

ecclesiastical architecture of the

Flemish Renaissance is almost as

destitute of

important

monuments as is the secular. Ste.

Anne, at

Bruges, fairly illustrates the

type,

which is characterized in general by

heaviness of detail and a cold and

bare

aspect

internally. The Renaissance in Belgium is

best exemplified, after all, by

minor

works

and ordinary dwellings, many of which

have considerable artistic

grace,

though

they are quaint rather than monumental

(Fig. 190). Stepped gables,

high

dormers,

and volutes flanking each

diminishing stage of the design,

give a certain

piquancy

to the street architecture of the

period.

HOLLAND.

Except

in the domain of realistic painting, the

Dutch have never

manifested

pre-eminent artistic endowments, and the

Renaissance produced in

Holland

few monuments of consequence. It began

there, as in many other

places,

with

minor works in the churches, due

largely to Flemish or Italian

artists. About the

middle

of the 16th century two native architects,

Sebastian

van Noye and

William

van

Noort,

first popularized the use of

carved pilasters and of gables or

steep

pediments

adorned with carved scallop-shells, in

remote imitation of the style

of

Francis

I. The principal monuments of the age

were town-halls, and, after the war

of

independence

in which the yoke of Spain was finally

broken (156679), local

administrative

buildings--mints, exchanges and the like.

The Town

Hall of

The

Hague

(1565), with

its stepped gable or great

dormer, its consoles,

statues, and

octagonal

turrets, may be said to have

inaugurated the style generally

followed after

the

war. Owing to the lack of stone, brick

was almost universally

employed, and

stone

imported by sea was only used in

edifices of exceptional cost and

importance.

Of

these the Town

Hall at

Amsterdam holds the first

place. Its fa�ade is of about

the

same

dimensions as the one at Antwerp, but

compares unfavorably with it in

its

monotony

and want of interest. The Leyden

Town Hall, by the

Fleming, Lieven

de

Key

(1597), the

Bourse or Exchange and the Hanse

House at Amsterdam, by Hendrik

de

Keyser,

are also worthy of mention, though many

lesser buildings, built of

brick

combined

with enamelled terra-cotta and stone,

possess quite as much artistic

merit.

DENMARK.

In

Denmark the monuments of the Renaissance

may almost be said to

be

confined to the reign of Christian IV.

(15881648), and do not include a

single

church

of any importance. The royal castles of

the Rosenborg

at

Copenhagen (1610)

and

the Fredericksborg

(15801624),

the latter by a Dutch architect, are

interesting

and

picturesque in mass, with their fanciful

gables, mullioned windows

and

numerous

turrets, but can hardly lay claim to

beauty of detail or purity of style.

The

Exchange

at Copenhagen, built of brick and stone

in the same general style

(1619

40),

is still less interesting both in

mass and detail.

The

only other important Scandinavian

monument deserving of special mention in

so

brief

a sketch as this is the Royal

Palace at

Stockholm,

Sweden (16981753), due

to

a foreign architect, Nicodemus

de Tessin. It is of

imposing dimensions, and

although

simple in external treatment, it

merits praise for the excellent

disposition of

its

plan, its noble court,

imposing entrances, and the general

dignity and

appropriateness

of its architecture.

MONUMENTS

(in

addition to those mentioned in

text). ENGLAND, TUDOR STYLE: Several

palaces

by Henry VIII., no longer extant;

Westwood, later rebuilt;

Gosfield Hall;

Harlaxton.--ELIZABETHAN:

Buckhurst, 1565; Kirby House, 1570,

both by Thorpe; Caius

College,

157075, by Theodore Have; "The

Schools," Oxford, by Thomas

Holt, 1600;

Beaupr�

Castle, 1600.--JACOBEAN: Tombs of Mary of Scotland

and of Elizabeth in

Westminster

Abbey; Audsley Inn; Bolsover

Castle, 1613; Heriot's Hospital,

Edinburgh,

1628.--CLASSIC or

ANGLO-ITALIAN: St. John's

College, Oxford;

Queen's House,

Greenwich;

Coleshill; all by Inigo

Jones, 162051; Amesbury, by Webb;

Combe Abbey;

Buckingham

and Montague Houses; The

Monument, London, 1670, by Wren;

Temple

Bar,

by the same; Winchester

Palace, 1683; Chelsea College;

Towers of Westminster

Abbey,

1696; St. Clement Dane's;

St. James's, Westminster;

St. Peter's, Cornhill,

and

many

others, all by

Wren.--18TH CENTURY:

Seaton Delaval and

Grimsthorpe, by Van

Brugh;

Wanstead House, by Colin

Campbell; Treasury Buildings, by

Kent.

The

most important Renaissance

buildings of BELGIUM and HOLLAND

have

been mentioned

in

the text.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.