|

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES |

| << RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS |

| RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS >> |

CHAPTER

XXII.

RENAISSANCE

ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Fergusson, M�ntz,

Palustre. Also Berty,

La

Renaissance

monumentale en France.

Ch�teau, Histoire

et caract�res de

l'architecture

en

France.

Daly, Motifs

historiques d'architecture et de

sculpture. De

Laborde, La

Renaissance

des arts � la cour de

France. Du

Cerceau, Les

plus excellents bastiments

de

France.

L�bke, Geschichte

der Renaissance in

Frankreich.

Mathews, The

Renaissance

under

the Valois Kings.

Palustre, La

Renaissance en France.

Pattison, The

Renaissance

of

the Fine Arts in

France.

Rouyer et Darcel, L'Art

architectural en France.

Sauvageot,

Choix

de palais, ch�teaux, h�tels, et

maisons de France.

ORIGIN

AND CHARACTER. The vitality

and richness of the Gothic style in

France,

even

in its decline in the fifteenth century,

long stood in the way of any

general

introduction

of classic forms. When the Renaissance

appeared, it came as a

foreign

importation,

introduced from Italy by the king and the nobility. It

underwent a

protracted

transitional phase, during which the

national Gothic forms and

traditions

were

picturesquely mingled with those of the

Renaissance. The campaigns of

Charles

VIII.

(1489), Louis XII. (1499), and Francis I. (1515), in

vindication of their

claims

to

the thrones of Naples and Milan, brought

these monarchs and their nobles

into

contact

with the splendid material and artistic

civilization of Italy, then in the full

tide

of the maturing Renaissance. They

returned to France, filled with the

ambition

to

rival the splendid palaces and gardens of

Italy, taking with them Italian artists

to

teach

their arts to the French. But while these

Italians successfully introduced

many

classic

elements and details into French

architecture, they wholly failed to

dominate

the

French master-masons and tailleurs

de pierre in

matters of planning and

general

composition.

The early Renaissance architecture of

France is consequently wholly

unlike

the Italian, from which it derived only minor

details and a certain

largeness

and

breadth of spirit.

PERIODS.

The

French Renaissance and its

sequent developments may be

broadly

divided

into three periods, with subdivisions

coinciding more or less

closely with

various

reigns, as follows:

I.

THE VALOIS PERIOD, or Renaissance proper, 14831589,

subdivided into:

a.

THE TRANSITION,

comprising the reigns of Charles VIII.

and Louis XII. (1483

1515),

and the early years of that of Francis

I.; characterized by a picturesque

mixture

of classic details with Gothic

conceptions.

b.

THE STYLE OF FRANCIS I.,

or Early Renaissance, from about 1520 to

that king's

death

in 1547; distinguished by a remarkable

variety and grace of composition

and

beauty

of detail.

c.

THE ADVANCED RENAISSANCE, comprising the

reigns of Henry II. (1547), Francis

II.

(1559),

Charles IX. (1560), and Henry III. (157489);

marked by the gradual

adoption

of the classic orders and a decline in

the delicacy and richness of the

ornament.

II.

THE BOURBON OR CLASSIC PERIOD (15891715):

a.

STYLE OF HENRY IV., covering his reign and

partly that of Louis XIII. (161045),

employing

the orders and other classic

forms with a somewhat heavy, florid

style of

ornament.

b.

STYLE OF LOUIS XIV., beginning in the preceding

reign and extending through that

of

Louis XIV. (16451715); the great age of

classic architecture in

France,

corresponding

to the Palladian in Italy.

III.

THE DECLINE OR ROCOCO PERIOD,

corresponding with the reign of Louis

XV.

(171574);

marked by pompous extravagance and

capriciousness.

During

this period a reaction set in

toward a severer classicism,

leading to the styles

of

Louis XVI. and of the Empire, to be

treated of in a later

chapter.

THE

TRANSITION. As

early as 1475 the new style made

its appearance in

altars,

tombs,

and rood-screens wrought by French

carvers with the collaboration of

Italian

artificers.

The tomb erected by Charles of Anjou to

his father in Le Mans

cathedral

(1475,

by Francesco

Laurana), the

chapel of St. Lazare in the

cathedral of Marseilles

(1483),

and the tomb of the children of Charles VIII. in Tours

cathedral (1506), by

Michel

Columbe, the

greatest artist of his time

in France, are examples. The

schools

of

Rouen and Tours were especially

prominent in works of this kind, marked

by

exuberant

fancy and great delicacy of

execution. In church architecture

Gothic

traditions

were long dominant, in spite

of the great numbers of Italian prelates

in

France.

It was in ch�teaux,

palaces, and dwellings that the new style

achieved its

most

notable triumphs.

EARLY

CH�TEAUX. The

castle of Charles VIII., at Amboise on

the Loire, shows

little

trace of Italian influence. It was under

Louis XII. that the transformation

of

French

architecture really began. The

Ch�teau

de Gaillon (of

which unfortunately

only

fragments remain in the �cole

des Beaux-Arts at Paris), built for the

Cardinal

George

of Amboise, between 1497 and 1509, by

Pierre

Fain,

was the masterwork of

the

Rouen school. It presented a

curious mixture of styles, with its

irregular plan, its

moat,

drawbridge, and round corner-towers, its

high roofs, turrets, and

dormers,

which

gave it, in spite of many Renaissance

details, a medi�val picturesqueness.

The

Ch�teau

de Blois (the

east and south wings of the

present group), begun for

Louis

XII.

about 1500, was the first of a

remarkable series of royal

palaces which are the

glory

of French architecture. It shows the new

influences in its horizontal

lines and

flat,

unbroken fa�ades of brick and

stone, rather than in its

architectural details

(Fig.

175).

The Ducal

Palace at Nancy and

the H�tel

de Ville at

Orl�ans, by Viart, show

a

similar

commingling of the classic and medi�val

styles.

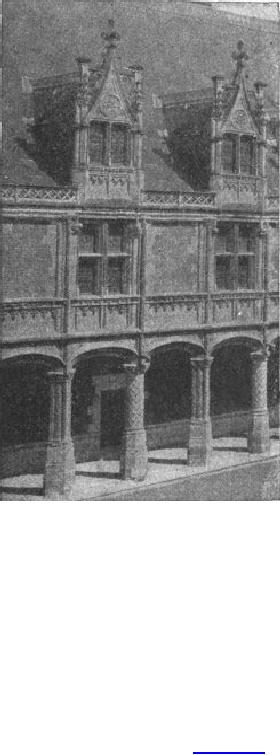

FIG.

175.--BLOIS, COURT FA�ADE OF

WING OF LOUIS XII.

STYLE

OF FRANCIS I. Early

in the reign of this monarch, and partly under the

lead

of

Italian artists, like il Rosso,

Serlio, and Primaticcio, classic

elements began to

dominate

the general composition and Gothic

details rapidly disappeared. A

simple

and

effective system of exterior

design was adopted in the

castles and palaces of this

period.

Finely moulded belt-courses at the

sills and heads of the windows marked

the

different

stories, and were crossed by a

system of almost equally

important vertical

lines,

formed by superposed pilasters

flanking the windows continuously

from

basement

to roof. The fa�ade was

crowned by a slight cornice and

open balustrade,

above

which rose a steep and lofty roof,

diversified by elaborate dormer

windows

like

long panels ornamented with

arabesques of great beauty, or with a

species of

baluster

shaft like a candelabrum,

were preferred to columns, and

were provided

with

graceful capitals of the Corinthianesque

type. The mouldings were minute

and

richly

carved; pediments were

replaced by steep gables, and

mullioned windows with

stone

crossbars were used in

preference to the simpler Italian

openings. In the earlier

monuments

Gothic details were still

used occasionally; and round

corner-towers,

high

dormers, and numerous turrets and

pinnacles appear even in the

ch�teaux of

later

date.

CHURCHES.

Ecclesiastical

architecture received but scant

attention under Francis I.,

and,

so far as it was practised, still

clung tenaciously to Gothic

principles. Among the

few

important churches of this period may be

mentioned St.

Etienne du Mont,

at

Paris

(151738), in which classic and Gothic

features appear in nearly

equal

proportions;

the east end of St.

Pierre, at

Caen, with rich external carving; and

the

great

parish church of St.

Eustache, at

Paris (1532, by Lemercier), in which

the plan

and

construction are purely Gothic, while the

details throughout belong to the

new

style,

though with little appreciation of the spirit and

proportions of classic art. New

fa�ades

were also built for a number of already

existing churches, among which

St.

Michel, at Dijon, is

conspicuous, with its vast

portal arch and imposing

towers. The

Gothic

towers of Tours cathedral were

completed with Renaissance lanterns

or

belfries,

the northern in 1507, the southern in 1547.

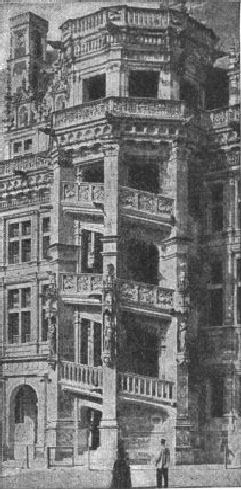

FIG.

176.--STAIRCASE TOWER,

BLOIS.

PALACES.

To the

palace at Blois begun by his

predecessor, Francis I. added

a

northern

and a western wing, completing the court.

The north wing is one of the

masterpieces

of the style, presenting toward the court

a simple and effective

composition,

with a rich but slightly projecting

cornice and a high roof with

elaborate

dormers.

This fa�ade is divided into two

unequal sections by the open

Staircase

Tower

(Fig.

176), a chef-d'oeuvre

in

boldness of construction as well as in

delicacy

and

richness of carving. The outer

fa�ade of this wing is a less ornate but

more

vigorous

design, crowned by a continuous

open loggia under the roof. More

extensive

than

Blois was Fontainebleau, the

favorite residence of the king and of

many of his

successors.

Following in parts the irregular plan of

the convent it replaced, its

other

portions

were more symmetrically

disposed, while the whole was treated

externally

in

a somewhat severe, semi-classic

style, singularly lacking in

ornament. Internally,

however,

this palace, begun in 1528 by Gilles

Le Breton,

was at that time the

most

splendid

in France, the gallery of Francis I.

being especially noted. The

Ch�teau

of

St.

Germain,

near Paris (1539, by Pierre

Chambiges), is of a

very different character.

Built

largely of brick, with flat balustraded

roof and deep buttresses

carrying three

ranges

of arches, it is neither Gothic nor

classic, neither fortress nor

palace in aspect,

but

a wholly unique conception.

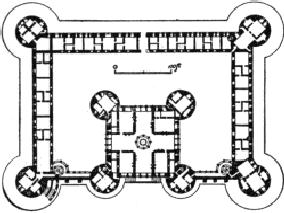

FIG.

177.--PLAN OF CHAMBORD.

The

rural ch�teaux and hunting-lodges erected

by Francis I. display the

greatest

diversity

of plan and treatment, attesting the

inventiveness of the French

genius,

expressing

itself in a new-found language,

whose formal canons it

disdained. Chief

among

them is the Ch�teau

of Chambord (Figs.

177, 178)--"a Fata Morgana in the

midst

of a wild, woody thicket," to use L�bke's

language. This extraordinary

edifice,

resembling

in plan a feudal castle with

curtain-walls, bastions, moat, and

donjon, is

in

its architectural treatment a

palace with arcades, open-stair

towers, a noble

double

spiral

staircase terminating in a graceful

lantern, and a roof of the most

bewildering

complexity

of towers, chimneys, and dormers (1526,

by Pierre

le Nepveu).

The

hunting-lodges

of La Muette and Chalvau, and the so-called

Ch�teau

de Madrid--all

three

demolished during or since the

Revolution--deserve mention, especially

the

last.

This consisted of two rectangular

pavilions, connected by a lofty

banquet-hall,

and

adorned externally with arcades in

Florentine style, and with medallions

and

reliefs

of della Robbia ware (1527, by

Gadyer).

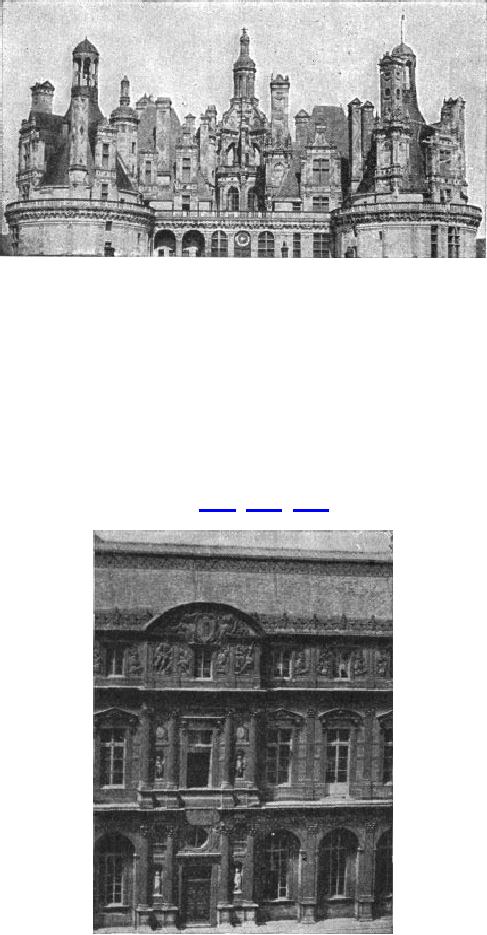

FIG.

178.--VIEW OF CHAMBORD.

THE

LOUVRE. By far the

most important of all the architectural

enterprises of this

reign,

in ultimate results, if not in original

extent, was the beginning of a new

palace

to

replace the old Gothic fortified

palace of the Louvre. To this task

Pierre Lescot was

summoned

in 1542, and the work of erection actually

begun in 1546. The new

palace,

in a sumptuous and remarkably dignified

classic style, was to have

covered

precisely

the area of the demolished fortress. Only

the southwest half, comprising

two

sides of the court, was,

however, undertaken at the outset

(Fig. 179). It

remained

for later monarchs to amplify the

original scheme, and ultimately

to

complete,

late in the present century, the most

extensive and beautiful of all the

FIG.

179.--DETAIL OF COURT OF LOUVRE,

PARIS.

Want

of space forbids more than a

passing reference to the rural castles of

the

nobility,

rivalling those of the king.

Among them Bury, La Rochefoucauld,

Bournazel,

and

especially Azay-le-Rideau

(1520) and

Chenonceaux

(151523),

may be

mentioned,

all displaying that love of rural

pleasure, that hatred of the city and

its

confinement,

which so distinguish the French from the Italian

Renaissance.

OTHER

BUILDINGS. The

H�tel-de-Ville

(town

hall), of Paris, begun

during this

reign,

from plans by Domenico

di Cortona (?),

and completed under Henry IV., was

the

most important edifice of a

class which in later periods

numbered many

interesting

structures. The town hall of Beaugency

(1527) is

one of the best of minor

public

buildings in France, and in its

elegant treatment of a simple

two-storied fa�ade

may

be classed with the Maison

Fran�ois I., at

Paris. This stood formerly

at Moret,

whence

it was transported to Paris and

re-erected about 1830 in somewhat

modified

form.

The large city houses of this period

are legion; we can mention

only the H�tel

Carnavalet

at Paris; the H�tel Bourgtheroude at

Rouen; the H�tel d'�coville at

Caen;

the

archbishop's palace at Sens, and a number

of houses in Orl�ans. The Tomb

of

Louis

XII., at

St. Denis, deserves especial

mention for its fine

proportions and

beautiful

arabesques.

THE

ADVANCED RENAISSANCE. By the

middle of the sixteenth century the

new

style

had lost much of its earlier

charm. The orders, used with

increasing frequency,

were

more and more conformed to

antique precedents. Fa�ades

were flatter and

simpler,

cornices more pronounced,

arches more Roman in

treatment, and a heavier

style

of carving took the place of the

delicate arabesques of the preceding

age. The

reigns

of Henry II. (154759) and Charles IX. (156074)

were especially

distinguished

by the labors of three celebrated

architects: Pierre

Lescot (151578),

who

continued the work on the southwest angle

of the Louvre; Jean

Bullant (1515

78),

to whom are due the right wing of Ecouen

and the porch of colossal

Corinthian

columns

in the left wing of the same, built under Francis I.;

and, finally, Philibert

de

l'Orme

(151570).

Jean

Goujon (151072)

also executed during this

period most of

the

remarkable architectural sculptures which

have made his name

one of the most

illustrious

in the annals of French art. Chief

among the works of de l'Orme was

the

palace

of the Tuileries, built under

Charles IX. for Cath�rine de M�dicis, not

far from

the

Louvre, with which it was ultimately

connected by a long gallery. Of the

vast

plan

conceived for this palace, and comprising

a succession of courts and wings,

only

a

part of one side was erected

(156472). This consisted of a

domical pavilion,

flanked

by low wings only a story and a half

high, to which were added two

stories

under

Henry IV., to the great advantage of the

design. Another masterpiece

was the

Ch�teau

d'Anet, built in

1552 by Henry II. for Diane de Poitiers, of

which,

unfortunately,

only fragments survive. This

beautiful edifice, while retaining

the

semi-military

moat and bastions of feudal

tradition, was planned with

classic

symmetry,

adorned with superposed orders, court

arcades, and rectangular

corner-

pavilions,

and provided with a domical cruciform

chapel, the earliest of its

class in

France.

All the details were unusually pure and

correct, with just enough of

freedom

and

variety to lend a charm wanting in

later works of the period. To the

reign of

Henry

II. belong also the ch�teaux of

Ancy-le-Franc, Verneuil, Chantilly

(the "petit

ch�teau,"

by Bullant), the banquet-hall over the

bridge at Chenonceaux (1556),

several

notable residences at Toulouse, and the

tomb of Francis I. at St. Denis.

The

ch�teaux

of Pailly

and

Sully,

distinguished by the sobriety and

monumental quality

of

their composition, in which the orders

are important elements,

belong to the reign

of

Charles IX., together with the Tuileries,

already mentioned.

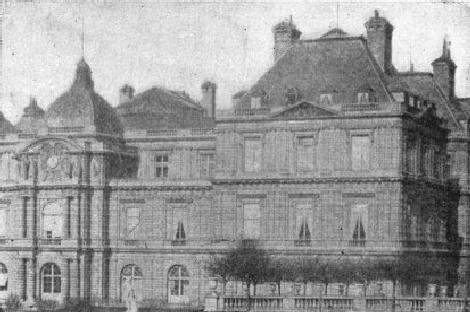

FIG.

180.--THE LUXEMBURG,

PARIS.

THE

CLASSIC PERIOD: HENRY IV. Under this

energetic but capricious

monarch

(15891610)

and his Florentine queen,

Marie de M�dicis, architecture

entered upon

a

new period of activity and a new stage of

development. Without the charm of

the

early

Renaissance or the stateliness of the age of

Louis XIV., it has a touch of the

Baroque,

attributable partly to the influence of

Marie de M�dicis and her Italian

prelates,

and partly to the Italian training of many of the

French architects. The

great

work

of this period was the extension of the

Tuileries by J.

B. du Cerceau, and

the

completion,

by M�t�zeau

and

others, of the long gallery next the

Seine, begun under

Henry

II., with the view of connecting the Tuileries with

the Louvre. In this part of

the

work colossal orders were

used with indifferent effect. Next in

importance was

the

addition to Fontainebleau of a great

court to the eastward, whose

relatively quiet

and

dignified style offers less

contrast than one might expect to the

other wings and

courts

dating from Francis I. More successful

architecturally than either of the

above

was

the Luxemburg

palace,

built for the queen by Salomon

De Brosse, in 1616

(Fig.

180).

Its plan presents the favorite French

arrangement of a main building

separated

from

the street by a garden or court, the

latter surrounded on three

sides by low

wings

containing the dependencies. Externally,

rusticated orders recall the

garden

front

of the Pitti at Florence; but the scale

is smaller, and the projecting

pavilions

and

high roofs give it a grace and

picturesqueness wanting in the Florentine

model.

The

Place

Royale, at

Paris, and the ch�teau of Beaumesnil,

illustrate a type of

brick-

and-stone

architecture much in vogue at this time,

stone quoins decorating

the

windows

and corners, and the orders being

generally omitted.

Under

Louis XIII. the Tuileries were

extended northward and the Louvre as built

by

Lescot

was doubled in size by the

architect Lemercier, the

Pavillon de l'Horloge

being

added

to form the centre of the enlarged court

fa�ade.

CHURCHES.

To this

reign belong also the most

important churches of the

period.

The

church of St.

Paul-St. Louis, at

Paris (1627, by Derrand),

displays the worst

faults

of the time, in the overloaded and

meaningless decoration of its

uninteresting

front.

Its internal dome is the earliest in

Paris. Far superior was the

chapel of the

Sorbonne, a

well-designed domical church by Lemercier, with a

sober and

appropriate

exterior treated with superposed

orders.

PERIOD

OF LOUIS XIV. This

was an age of remarkable literary and

artistic activity,

pompous

and pedantic in many of its

manifestations, but distinguished also

by

productions

of a very high order. Although

contemporary with the Italian

Baroque--

Bernini

having been the guest of

Louis XIV.--the architecture of this

period was free

from

the wild extravagances of that style. In

its often cold and correct

dignity it

resembled

rather that of Palladio, making

large use of the orders in

exterior design,

and

tending rather to monotony than to

overloaded decoration. In interior

design

there

was more of lightness and

caprice. Papier-mach� and stucco

were freely used in

a

fanciful style of relief

ornamentation by scrolls, wreaths,

shells, etc., and

decorative

panelling

was much employed. The whole was

saved from triviality only by the

controlling

lines of the architecture which framed

it. But it was better suited

to

cabinet-work

or to the prettinesses of the boudoir than to

monumental interiors. The

Galerie

d'Apollon, built

during this reign over the

Petite Galerie in the

Louvre,

escapes

this reproach, however, by the sumptuous

dignity of its interior

treatment.

VERSAILLES.

This

immense edifice, built about an

already existing villa of

Louis

XIII.,

was the work of Levau

and

J.

H. Mansart (16471708).

Its erection, with the

laying

out of its marvellous park,

almost exhausted the resources of the

realm, but

with

results quite incommensurate with the

outlay. In spite of its vastness,

its

exterior

is commonplace; the orders are

used with singular monotony, which is

not

redeemed

by the deep breaks and projections of the

main front. There is no

controlling

or dominant feature; there is no

adequate entrance or approach; the

grand

staircases

are badly placed and unworthily

treated, and the different elements of

the

plan

are combined with singular

lack of the usual French

sense of monumental and

rational

arrangement. The chapel is by far the

best single feature in the

design.

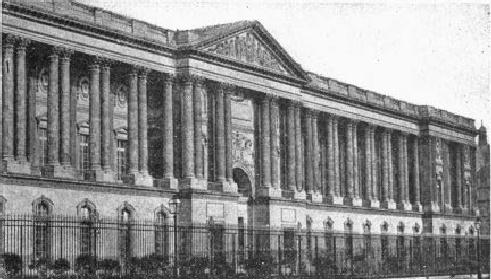

Far

more successful was the

completion of the Louvre, in 1688, from the

designs of

Claude

Perrault, the court

physician, whose plans were

fortunately adopted in

preference

to those of Bernini. For the

east front he designed a

magnificent

Corinthian

colonnade nearly 600 feet

long, with coupled columns upon a

plain high

basement,

and with a central pediment and terminal

pavilions (Fig. 181). The whole

forms

one of the most imposing

fa�ades in existence; but it is a mere

decoration,

having

no practical relation to the building

behind it. Its height required the

addition

of

a third story to match it on the north and

south sides of the court, which as

thus

completed

quadrupled the original area

proposed by Lescot. Fortunately the

style of

Lescot's

work was retained throughout in the court

fa�ades, while externally the

colonnade

was recalled on the south front by a

colossal order of pilasters. The

Louvre

as

completed by Louis XIV. was a

stately and noble palace, as

remarkable for the

surpassing

excellence of the sculptures of Jean

Goujon as for the dignity and

beauty

of

its architecture. Taken in connection

with the Tuileries, it was unrivalled by

any

palace

in Europe except the

Vatican.

FIG.

181.--COLONNADE OF LOUVRE.

OTHER

BUILDINGS. To

Louis XIV. is also due the

vast but uninteresting H�tel

des

Invalides

or

veteran's asylum, at Paris, by J. H.

Mansart. To the chapel of this

institution

was added, in 16801706, the

celebrated Dome

of the

Invalides,

a

masterpiece by the same architect. In

plan it somewhat resembles

Bramante's

scheme

for St. Peter's--a Greek

cross with domical chapels in the four

angles and a

dome

over the centre. The exterior

(Fig. 182), with the lofty gilded dome on

a high

drum

adorned with engaged columns, is

somewhat high for its breadth, but is

a

harmonious

and impressive design; and the interior,

if somewhat cold, is elegant

and

well

proportioned. The chief innovation in the

design was the wide

separation of the

interior

stone dome from the lofty exterior

decorative cupola and lantern of

wood,

this

separation being designed to

meet the conflicting demands of

internal and

external

effect. To the same architect is

due the formal monotony of the Place

Vend�me, all the

houses surrounding it being

treated with a uniform architecture

of

colossal

pilasters, at once monumental and

inappropriate. One of the most

pleasing

designs

of the time is the Ch�teau

de Maisons (1658), by

F.

Mansart,

uncle of J. H.

Mansart.

In this the proportions of the central and

terminal pavilions, the mass

and

lines

of the steep roof �

la Mansarde, the

simple and effective use of the

orders, and

the

refinement of all the details impart a

grace of aspect rare in

contemporary works.

The

same qualities appear also

in the Val-de-Gr�ce, by F.

Mansart and Lemercier,

a

domical church of excellent proportions

begun under Louis XIII. The want of

space

forbids

mention of other buildings of this

period.

FIG.

182.--DOME OF THE INVALIDES.

THE

DECLINE. Under

Louis XV. the pedantry of the classic

period gave place to

a

protracted

struggle between license and the

severest classical correctness.

The

exterior

designs of this time were

often even more

uninteresting and bare than under

Louis

XIV.; while, on the other hand, interior

decoration tended to the extreme

of

extravagance

and disregard of constructive propriety.

Contorted lines and

crowded

scrolls,

shells, and palm-leaves adorned the

mantelpieces, cornices, and ceilings,

to

the

almost complete suppression of

straight lines.

While

these tendencies prevailed in many

directions, a counter-current of

severe

classicism

manifested itself in the designs of a

number of important public

buildings,

in

which it was sought to copy the

grandeur of the old Roman colonnades

and

arcades.

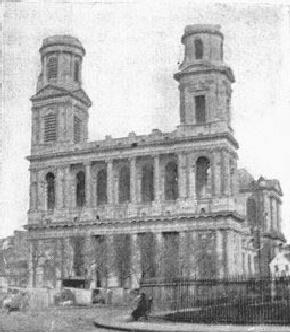

The important church of St.

Sulpice at

Paris (Fig. 183) is an

excellent

example

of this. Its interior, dating from the

preceding century, is well designed,

but

in

no wise a remarkable composition,

following Italian models. The fa�ade,

added in

1755

by Servandoni,

is, on the other hand, one of the

most striking

architectural

objects

in the city. It is a correct and well proportioned

classic composition in two

stories--an

Ionic arcade over a Doric

colonnade, surmounted by two lateral

turrets.

Other

monuments of this classic revival will be

noticed in Chapter XXV.

FIG.

183.--FA�ADE OF ST. SULPICE,

PARIS.

PUBLIC

SQUARES. Much

attention was given to the

embellishment of open

spaces

in

the cities, for which the classic style

was admirably suited. The

most important

work

of this kind was that on the north side of the

Place de la Concorde, Paris.

This

splendid

square, perhaps, on the whole, the

finest in Europe (though many of

its best

features

belong to a later date), was

at this time adorned with the two

monumental

colonnades

by Gabriel.

These colonnades, which form the

decorative fronts for

blocks

of

houses, deserve praise for the

beauty of their proportions, as well as for

the

excellent

treatment of the arcade on which they

rest, and of the pavilions at the

ends.

IN

GENERAL. French

Renaissance architecture is marked by

good proportions and

harmonious

and appropriate detail. Its most

interesting phase was

unquestionably

that

of Francis I., so far, at least, as

concerns exterior design. It

steadily progressed,

however,

in its mastery of planning; and in

its use of projecting

pavilions crowned by

dominant

masses of roof, it succeeded in

preserving, even in severely

classic designs,

a

picturesqueness and variety otherwise

impossible. Roofs, dormers,

chimneys, and

staircases

it treated with especial success; and in

these matters, as well as in

monumental

dispositions of plan, the French have

largely retained their

pre-eminence

to

our own day.

MONUMENTS.

(Mainly

supplementary to text. Ch. =

ch�teau; P. = palace; C. =

cathedral;

Chu. = church; H. = h�tel; T.H. = town

hall.)

TRANSITION:

Blois, E. wing, 1499; Ch.

Meillant; Ch. Chaumont; T.H.

Amboise, 150205.

FRANCIS I.:

Ch. Nantouillet, 151725; Ch.

Blois, W. wing (afterward

demolished) and

N.

wing, 152030; H. Lallemant, Bourges,

1520; Ch. Villers-Cotterets, 152059; P.

of

Archbishop,

Sens, 152135; P. Fontainebleau (Cour

Ovale, Cour d'Adieux,

Gallery

Francis

I., 152734; Peristyle, Chapel St.

Saturnin, 154047, by Gilles

le Breton;

Cour

du

Cheval Blanc, 152731, by P.

Chambiges); H.

Bernuy, Toulouse, 152839;

P.

Granvelle, Besan�on, 153240; T.H.

Niort, T.H. Loches, 153243: H. de

Ligeris

(Carnavalet),

Paris, 1544, by P.

Lescot;

churches of Gisors, nave and

fa�ade, 1530; La

Dalbade,

Toulouse, portal, 1530; St.

Symphorien Tours, 1531; Chu.

Tilli�res, 153446.

ADVANCED RENAISSANCE: Fontaine des

Innocents, Paris, 154750, by

P.

Lescot and

J.

Goujon;

tomb Francis I., at St.

Denis, 1555, by Ph.

de l'Orme; H.

Catelan, Toulouse,

1555;

tomb Henry II., at St.

Denis, 1560; portal S. Michel,

Dijon, 1564; Ch.

Sully,

1567;

T.H. Arras, 1573; P. Fontainebleau (Cour

du Cheval Blanc remodelled,

156466,

by

P.

Girard;

Cour de la Fontaine, same

date); T.H. Besan�on, 1582; Ch.

Charleval,

1585,

by, J.

B. du Cerceau.

STYLE OF HENRY IV.: P. Fontainebleau (Galerie

des Cerfs, Chapel of the

Trinity, Baptistery,

etc.);

P. Tuileries (Pav. de Flore, by

du

Cerceau,

15901610; long gallery

continued);

H�tel

Vog��, at Dijon, 1607; Place

Dauphine, Paris, 1608; P. de Justice,

Paris, Great

Hall,

by S.

de Brosse, 1618; H.

Sully, Paris, 162439; P. Royal,

Paris, by J.

Lemercier,

for

Cardinal Richelieu, 162739; P.

Louvre doubled in size, by

the same; P.

Tuileries

(N.

wing, and Pav. Marsan,

long gallery completed); H.

Lambert, Paris; T.H.

Reims,

1627;

Ch. Blois, W. wing for

Gaston d'Orl�ans, by F.

Mansart, 1635;

fa�ade St. �tienne

du

Mont, Paris, 1610; of St. Gervais,

Paris, 161621, by S.

de Brosse.

STYLE OF LOUIS XIV.: T.H. Lyons, 1646; P. Louvre, E.

colonnade and court

completed,

166070;

Tuileries altered by Le Vau, 1664;

observatory at Paris, 166772; arch

of St.

Denis,

Paris, 1672, by Blondel;

Arch of St. Martin, 1674, by

Bullet;

Banque de France,

H.

de Luyne, H. Soubise, all in

Paris; Ch. Chantilly; Ch. de

Tanlay; P. St. Cloud; Place

des

Victoires,

1685; Chu. St. Sulpice,

Paris, by Le

Vau (fa�ade,

1755); Chu. St. Roch,

Paris,

1653,

by Lemercier

and

de

Cotte;

Notre Dame des Victoires,

Paris, 1656, by Le

Muet and

Bruant.

THE DECLINE:

P. Bourbon, 1722; T.H. Rouen; Halle

aux Bl�s (recently

demolished), 1748;

�cole

Militaire, 175258, by Gabriel; P.

Louvre, court completed, 1754, by

the same;

Madeleine

begun, 1764; H. des Monnaies

(Mint), by Antoine;

�cole de M�decine, 1774,

by

Gondouin; P.

Royal, Great Court, 1784, by

Louis;

Th��tre Fran�ais, 1784 (all

the

above

at Paris); Grand Th��tre,

Bordeaux, 17851800, by Louis;

Pr�fecture at Bordeaux,

by

the same; Ch. de Compiegne,

1770, by Gabriel; P.

Versailles, theatre by the

same;

H.

Montmorency, Soubise, de Varennes,

and the Petit Luxembourg,

all at Paris, by de

Cotte;

public squares at Nancy,

Bordeaux, Valenciennes, Rennes,

Reims.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.