|

CHAPTER

XX.

EARLY

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Anderson, Architecture

of the Renaissance in

Italy.

Burckhardt,

The

Civilization of the

Renaissance;

Geschichte

der Renaissance in

Italien;

Der

Cicerone.

Cellesi, Sei

Fabbriche di Firenze.

Cicognara, Le

Fabbriche pi� cospicue di

Venezia.

Durm, Die

Baukunst der Renaissance in

Italien (in

Hdbuch.

d. Arch.).

Fergusson,

History

of Modern Architecture.

Geym�ller, La

Renaissance en Toscane.

Montigny

et Famin, Architecture

Toscane.

Moore, Character

of Renaissance

Architecture. M�ntz,

La

Renaissance en Italie et en France �

l'�poque de Charles

VIII.

Palustre,

L'Architecture

de la Renaissance.

Pater, Studies

in the Renaissance.

Symonds,

The

Renaissance of the Fine Arts

in Italy.

Tosi and Becchio, Altars,

Tabernacles, and

Tombs.

THE

CLASSIC REVIVAL. The

abandonment of Gothic architecture in

Italy and the

substitution

in its place of forms

derived from classic models

were occasioned by no

sudden

or merely local revolution. The

Renaissance was the result of a

profound and

universal

intellectual movement, whose

roots may be traced far back into the

Middle

Ages,

and which manifested itself first in

Italy simply because there the

conditions

were

most propitious. It spread through

Europe just as rapidly as similar

conditions

appearing

in other countries prepared the way for

it. The essence of this

far-reaching

movement

was the protest of the individual

reason against the trammels of

external

and

arbitrary authority--a protest which found

its earliest organized

expression in

the

Humanists. In its assertion of the

intellectual and moral rights of the

individual,

the

Renaissance laid the foundations of

modern civilization. The same

spirit, in

rejecting

the authority and teachings of the Church in

matters of purely secular

knowledge,

led to the questionings of the precursors

of modern science and the

discoveries

of the early navigators. But in nothing

did the reaction against

medi�val

scholasticism

and asceticism display itself

more strikingly than in the joyful

enthusiasm

which marked the pursuit of classic

studies. The long-neglected

treasures

of

classic literature were

reopened, almost rediscovered, in the

fourteenth century by

the

immortal trio--Dante, Petrarch, and

Boccaccio. The joy of living, the

hitherto

forbidden

delight in beauty and pleasure for their

own sakes, the exultant

awakening

to

the sense of personal freedom, which

came with the bursting of medi�val

fetters,

found

in classic art and literature their most

sympathetic expression. It was in

Italy,

where

feudalism had never fully established

itself, and where the municipalities

and

guilds

had developed, as nowhere else, the

sense of civic and personal

freedom, that

these

symptoms first manifested

themselves. In Italy, and above all in the

Tuscan

cities,

they appeared throughout the fourteenth

century in the growing

enthusiasm

for

all that recalled the antique culture,

and in the rapid advance of luxury

and

refinement

in both public and private

life.

THE

RENAISSANCE OF THE ARTS. Classic

Roman architecture had never

lost its

influence

on the Italian taste. Gothic art,

already declining in the West, had

never

been

in Italy more than a borrowed garb,

clothing architectural conceptions

classic

rather

than Gothic in spirit. The antique

monuments which abounded on every

hand

were

ever present models for the

artist, and to the Florentines of the

early fifteenth

century

the civilization which had created them

represented the highest ideal

of

human

culture. They longed to revive in

their own time the glories of

ancient Rome,

and

appropriated with uncritical and

undiscriminating enthusiasm the good and

the

bad,

the early and the late forms of

Roman art, Na�vely unconscious of the

disparity

between

their own architectural conceptions and

those they fancied they

imitated,

they

were, unknown to themselves, creating a

new style, in which the details of

Roman

art were fitted in novel

combinations to new requirements. In

proportion as

the

Church lost its hold on the

culture of the age, this new architecture

entered

increasingly

into the service of private luxury and

public display. It created, it is

true,

striking

types of church design, and made of the

dome one of the most

imposing of

external

features; but its most

characteristic products were

palaces, villas,

council

halls,

and monuments to the great and the

powerful. The personal element in

design

asserted

itself as never before in the growth of

schools and the development of

styles.

Thenceforward

the history of Italian architecture

becomes the history of the

achievements

of individual artists.

EARLY

BEGINNINGS. Already

in the 13th century the pulpits of Niccolo

Pisano at

Sienna

and Pisa had revealed that master's

direct recourse to antique

monuments for

inspiration

and suggestion. In the frescoes of Giotto

and his followers, and in the

architectural

details of many nominally Gothic

buildings, classic forms had

appeared

with

increasing frequency during the

fourteenth century. This was

especially true in

Florence,

which was then the artistic capital of

Italy. Never, perhaps, since the

days

of

Pericles, had there been

another community so permeated with the

love of beauty

in

art, and so endowed with the capacity to

realize it. Nowhere else in

Europe at that

time

was there such strenuous

life, such intense feeling,

or such free course

for

individual

genius as in Florence. Her artists, with

unexampled versatility,

addressed

themselves

with equal success to goldsmiths' work,

sculpture, architecture and

engineering--often

to painting and poetry as well; and they

were quick to catch

in

their

art the spirit of the classic revival.

The new movement achieved its

first

architectural

triumph in the dome of the cathedral of

Florence (142064); and it was

Florentine--or

at least Tuscan--artists who planted in

other centres the seeds of

the

new

art that were to spring up in the local

and provincial schools of Sienna,

Milan,

Pavia,

Bologna, and Venice, of Brescia,

Lucca, Perugia, and Rimini, and many

other

North

Italian cities. The movement asserted

itself late in Rome and

Naples, as an

importation

from Northern Italy, but it bore abundant fruit in

these cities in its

later

stages.

PERIODS.

The

classic styles which grew up out of the

Renaissance may be divided

for

convenience into four periods.

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE or

FORMATIVE

PERIOD,

142090; characterized by the

grace

and

freedom of the decorative detail,

suggested by Roman prototypes and

applied to

compositions

of great variety and

originality.

THE HIGH

RENAISSANCE or

FORMALLY

CLASSIC PERIOD, 14901550. During this

period

classic

details were copied with

increasing fidelity, the orders

especially appearing in

almost

all compositions; decoration meanwhile

losing somewhat in grace

and

freedom.

THE EARLY BAROQUE (or BAROCO), 15501600; a period

of classic formality

characterized

by the use of colossal orders,

engaged columns and rather

scanty

decoration.

THE DECLINE or

LATER

BAROQUE,

marked by poverty of invention in the

composition

and

a predominance of vulgar sham and

display in the decoration. Broken

pediments,

huge

scrolls, florid stucco-work and a

general disregard of architectural

propriety

were

universal.

During

the eighteenth century there was a

reaction from these extravagances,

which

showed

itself in a return to the servile copying

of classic models, sometimes

not

without

a certain dignity of composition and

restraint in the decoration.

By

many writers the name Renaissance is

confined to the first period.

This is correct

from

the etymological point of view; but it is impossible

to dissociate the first

period

historically

from those which followed it, down to the final

exhaustion of the artistic

movement

to which it gave birth, in the heavy

extravagances of the Rococo.

FIG.

158.--EARLY RENAISSANCE CAPITAL,

PAL. ZORZI, VENICE.

Another

division is made by the Italians, who

give the name of the Quattrocento

to

the

period which closed with the end of the

fifteenth century, Cinquecento

to

the

sixteenth

century, and Seicento

to the

seventeenth century or Rococo. It

has,

however,

become common to confine the

use of the term Cinquecento to the first

half

of

the sixteenth century.

CONSTRUCTION

AND DETAIL. The

architects of the Renaissance

occupied

themselves

more with form than with construction, and

rarely set themselves

constructive

problems of great difficulty. Although

the new architecture began with

the

colossal dome of the cathedral of

Florence, and culminated in the

stupendous

church

of St. Peter at Rome, it was

pre-eminently an architecture of palaces

and

villas,

of fa�ades and of decorative display.

Constructive difficulties were

reduced to

their

lowest terms, and the constructive

framework was concealed, not

emphasized,

by

the decorative apparel of the design.

Among the masterpieces of the

early

Renaissance

are many buildings of small

dimensions, such as gates,

chapels, tombs

and

fountains. In these the individual

fancy had full sway, and produced

surprising

results

by the beauty of enriched mouldings, of

carved friezes with infant

genii,

wreaths

of fruit, griffins, masks and scrolls; by

pilasters covered with arabesques

as

delicate

in modelling as if wrought in silver; by

inlays of marble, panels of

glazed

terra-cotta,

marvellously carved doors,

fine stucco-work in relief,

capitals and

cornices

of wonderful richness and variety. The

Roman orders appeared only in

free

imitations,

with panelled and carved pilasters for

the most part instead of

columns,

and

capitals of fanciful design,

recalling remotely the Corinthian by

their volutes and

leaves

(Fig. 158). Instead of the low-pitched

classic pediments, there

appears

frequently

an arched cornice enclosing a

sculptured lunette. Doors and

windows

were

enclosed in richly carved frames,

sometimes arched and sometimes

square.

Fa�ades

were flat and unbroken, depending mainly

for effect upon the distribution

and

adornment of the openings, and the design

of doorways, courtyards and

cornices.

Internally vaults and flat ceilings of

wood and plaster were about

equally

common,

the barrel vault and dome occurring far

more frequently than the

groined

vault.

Many of the ceilings of this period are

of remarkable richness and

beauty.

THE

EARLY RENAISSANCE IN FLORENCE: THE DUOMO.

In the

year 1417 a

public

competition was held for

completing the cathedral of Florence by a

dome over

the

immense octagon, 143 feet in

diameter. Filippo

Brunelleschi,

sculptor and

architect

(13771446), who with Donatello had journeyed to

Rome to study there

the

masterworks of ancient art, after

demonstrating the inadequacy of all

the

solutions

proposed by the competitors, was finally

permitted to undertake the

gigantic

task according to his own

plans. These provided for an

octagonal dome in

two

shells, connected by eight

major and sixteen minor ribs, and

crowned by a

lantern

at the top (Fig. 159). This wholly

original conception, by which for the

first

time

(outside of Moslem art) the

dome was made an external

feature fitly terminating

in

the light forms and upward movement of a

lantern, was carried out

between the

years

1420 and 1464. Though in no wise an imitation of

Roman forms, it was

classic

in its spirit, in its

vastness and its simplicity of

line, and was made

possible

solely

by Brunelleschi's studies of Roman

design and construction (Fig.

160).

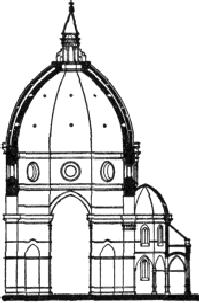

FIG.

159.--SECTION OF DOME OF DUOMO,

FLORENCE.

OTHER

CHURCHES. From

Brunelleschi's designs were

also erected the Pazzi

Chapel

in

Sta. Croce, a charming

design of a Greek cross

covered with a dome at the

intersection,

and preceded by a vestibule with a richly

decorated vault; and the two

great

churches of S.

Lorenzo (1425) and

S.

Spirito (14331476,

Fig. 161). Both

reproduced

in a measure the plan of the Pisa

Cathedral, having a three-aisled

nave

and

transepts, with a low dome over the

crossing. The side aisles

were covered with

domical

vaults and the central aisles with flat

wooden or plaster ceilings. All

the

details

of columns, arches and mouldings

were imitated from Roman

models, and yet

the

result was something

entirely new. Consciously or

unconsciously, Brunelleschi

was

reviving Byzantine rather than

Roman conceptions in the planning and

structural

design

of these domical churches, but the

garb in which he clothed them was

Roman,

at

least in detail. The Old

Sacristy of S.

Lorenzo was another domical

design of great

beauty.

From

this time on the new style was in

general use for church designs.

L.

B. Alberti

(140473),

who had in Rome mastered classic

details more thoroughly

than

Brunelleschi,

remodelled the church of S.

Francesco at

Rimini

with

Roman pilasters

and

arches, and with engaged orders in the

fa�ade, which, however, was

never

completed.

His great work was the church of

S.

Andrea at

Mantua, a

Latin cross in

plan,

with a dome at the intersection (the

present high dome dating

however, only

from

the 18th century) and a fa�ade to which the

conception of a Roman triumphal

arch

was skilfully adapted. His fa�ade of

incrusted marbles for the church of S.

M.

Novella

at Florence was a less

successful work, though its flaring

consoles over the

side

aisles established an unfortunate

precedent frequently imitated in

later churches.

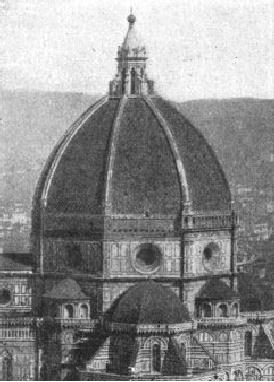

FIG.

160.--EXTERIOR OF DOME OF DUOMO,

FLORENCE.

A

great activity in church-building

marked the period between 1475 and 1490.

The

plans

of the churches erected about this

time throughout north Italy display

an

interesting

variety of arrangements, in nearly all of

which the dome is combined with

the

three-aisled cruciform plan, either as a

central feature at the crossing or as

a

domical

vault over each bay. Bologna and

Ferrara possess a number of churches

of

this

kind. Occasionally the basilican

arrangement was followed, with

columnar

arcades

separating the aisles. More often,

however, the pier-arches were of

the

Roman

type, with engaged columns or

pilasters between them. The

interiors,

presumably

intended to receive painted

decorations, were in most

cases somewhat

bare

of ornament, pleasing rather by

happy proportions and effective

vaulting or rich

flat

ceilings, panelled, painted and

gilded, than by elaborate architectural

detail.

A

similar scantiness of ornament is to be

remarked in the exteriors, excepting

the

fa�ades,

which were sometimes highly ornate; the

doorways, with columns,

pediments,

sculpture and carving, receiving

especial attention. High external

domes

did

not come into general use until the next

period. In Milan, Pavia, and some

other

Lombard

cities, the internal cupola

over the crossing was,

however, covered

externally

by a lofty structure in diminishing

stages, like that of the Certosa at

Pavia

(Fig.

152), or that erected by Bramante for the church of S.

M. delle Grazie at Milan.

At

Prato, in the church of the Madonna

delle Carceri (14951516),

by Giuliano

da

S.

Gallo, the type of

the Pazzi chapel reappears in a

larger scale; the plan is

cruciform,

with equal or nearly equal

arms covered by barrel

vaults, at whose

intersection

rises a dome of moderate

height on pendentives. This

charming edifice,

with

its unfinished exterior of white

marble, its simple and

dignified lines, and

internal

embellishments in della-Robbia ware, is

one of the masterpieces of the

period.

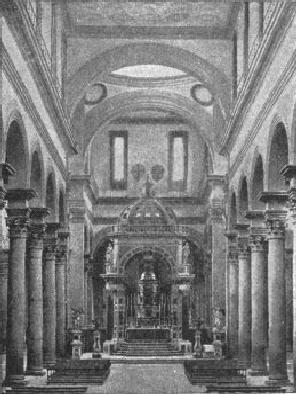

FIG.

161.--INTERIOR OF S. SPIRITO,

FLORENCE.

In

the designing of chapels and oratories

the architects of the early

Renaissance

attained

conspicuous success, these

edifices presenting fewer

structural limitations

and

being more purely decorative in

character than the larger churches.

Such fa�ades

as

that of S.

Bernardino at

Perugia and of the Frati

di S. Spirito at

Bologna are

among

the most delightful products of the

decorative fancy of the 15th

century.

FLORENTINE

PALACES. While

the architects of this period failed to

develop any

new

and thoroughly satisfactory

ecclesiastical type, they attained

conspicuous

success

in palace-architecture. The Riccardi

palace

in Florence (1430) marks the

first

step

of the Renaissance in this direction. It

was built for the great Cosimo di

Medici

by

Michelozzi

(13971473),

a contemporary of Brunelleschi and

Alberti, and a man

of

great talent. Its imposing

rectangular fa�ade, with widely spaced

mullioned

windows

in two stories over a massive

basement, is crowned with a classic

cornice of

unusual

and perhaps excessive size. In

spite of the bold and fortress-like

character of

the

rusticated masonry of these

fa�ades, and the medi�val look they

seem to present

to

modern eyes, they marked a

revolution in style and established a

type frequently

imitated

in later years. The courtyard, in

contrast with this stern exterior,

appears

light

and cheerful (Fig. 162). Its wall is

carried on round arches borne by

columns

with

Corinthianesque capitals, and the arcade

is enriched with sculptured

medallions.

The

Pitti Palace, by

Brunelleschi (1435), embodies the same

ideas on a

more

colossal scale, but lacks the

grace of an adequate cornice. A

lighter and more

ornate

style appeared in 1460 in the P.

Rucellai, by

Alberti, in which for the first

time

classical pilasters in superposed

stages were applied to a

street fa�ade. To

avoid

the

dilemma of either insufficiently

crowning the edifice or making the

cornice too

heavy

for the upper range of pilasters,

Alberti made use of

brackets, occupying the

width

of the upper frieze, and converting the

whole upper entablature into a

cornice.

But

this compromise was not quite

successful, and it remained for later

architects in

Venice,

Verona, and Rome to work out more

satisfactory methods of applying

the

orders

to many-storied palace fa�ades. In the

great P.

Strozzi (Fig.

163), erected in

1490

by Benedetto

da Majano and

Cronaca, the

architects reverted to the earlier

type

of

the P. Riccardi, treating it with greater

refinement and producing one of

the

noblest

palaces of Italy.

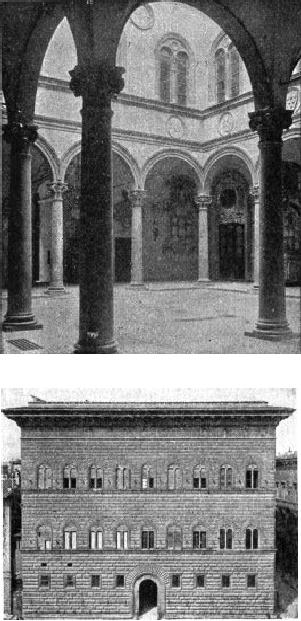

FIG.

162.--COURTYARD OF RICCARDI PALACE,

FLORENCE.

FIG.

163.--FA�ADE OF STROZZI PALACE,

FLORENCE.

COURTYARDS;

ARCADES. These

palaces were all built around

interior courts,

whose

walls rested on columnar

arcades, as in the P. Riccardi (Fig.

162). The origin

of

these arcades may be found in the arcaded

cloisters of medi�val

monastic

churches,

which often suggest classic

models, as in those of St.

Paul-beyond-the-

Walls

and St. John Lateran at

Rome. Brunelleschi not only introduced

columnar

arcades

into a number of cloisters and palace

courts, but also used them

effectively

as

exterior features in the Loggia

S. Paolo and the

Foundling Hospital (Ospedale

degli

Innocenti) at

Florence. The chief drawback in

these light arcades was

their

inability

to withstand the thrust of the vaulting

over the space behind them, and

the

consequent

recourse to iron tie-rods where

vaulting was used. The

Italians, however,

seemed

to care little about this

disfigurement.

MINOR

WORKS. The

details of the new style were

developed quite as rapidly

in

purely

decorative works as in monumental

buildings. Altars, mural

monuments,

tabernacles,

pulpits and ciboria

afforded

scope for the genius of the

most

distinguished

artists. Among those who

were specially celebrated in

works of this

kind

should be named Lucca

della Robbia (140082)

and his successors, Mino

da

Fiesole

(143184)

and Benedetto

da Majano (144297).

Possessed of a wonderful

fertility

of invention, they and their pupils

multiplied their works in

extraordinary

number

and variety, not only throughout north Italy, but

also in Rome and

Naples.

Among

the most famous examples of this

branch of design may be mentioned

a

pulpit

in Sta. Croce by B. da Majano; a

terra-cotta fountain in the sacristy of S.

M.

Novella,

by the della Robbias; the Marsupini tomb

in Sta. Croce, by Desiderio

da

Settignano

(all

in Florence); the della Rovere tomb in S.

M. del Popolo, Rome,

by

Mino

da Fiesole, and in the Cathedral at Lucca

the Noceto tomb and the Tempietto,

by

Matteo

Civitali. It

was in works of this character that the

Renaissance oftenest

made

its first appearance in a new

centre, as was the case in

Sienna, Pisa, Lucca,

Naples,

etc.

NORTH

ITALY. Between

1450 and 1490 the Renaissance presented in

Sienna, in a

number

of important palaces, a sharp

contrast to the prevalent Gothic

style of that

city.

The P.

Piccolomini--a

somewhat crude imitation of the P.

Riccardi in

Florence--dates

from 1463; the P.

del Governo was

built 1469, and the Spannocchi

Palace

in 1470. In

1463 Ant.

Federighi built

there the Loggia

del Papa.

About the

same

time Bernardo

di Lorenzo was

building for Pope Pius II.

(�neas Sylvius

Piccolomini)

an entirely new city, Pienza, with a

cathedral, archbishop's palace,

town

hall

and Papal residence (the

P.

Piccolomini), which

are interesting if not

strikingly

original

works. Pisa possesses few

early Renaissance structures,

owing to the utter

prostration

of her fortunes in the 15th century, and the dominance

of Pisan Gothic

traditions.

In Lucca, besides a wealth of minor

monuments (largely the work of

Matteo

Civitali, 14351501) in various

churches, a number of palaces date

from

this

period, the most important

being the P.

Pretorio and P.

Bernardini. To Milan the

Renaissance

was carried by the Florentine

masters Michelozzi

and

Filarete, to

whom

are

respectively due the Portinari

Chapel in S.

Eustorgio (1462) and the earlier

part

of

the great Ospedale

Maggiore (1457). In the

latter, an edifice of brick with

terra-

cotta

enrichments, the windows were Gothic in

outline--an unusual mixture of

styles,

even in Italy. The munificence of the

Sforzas, the hereditary tyrants of

the

province,

embellished the semi-Gothic Certosa

of

Pavia with a new marble

fa�ade,

begun

1476 or 1491, which in its fanciful and

exuberant decoration, and the

small

scale

of its parts, belongs

properly to the early Renaissance.

Exquisitely beautiful in

detail,

it resembles rather a magnified

altar-piece than a work of

architecture,

properly

speaking. Bologna and Ferrara

developed somewhat late in the century

a

strong

local school of architecture,

remarkable especially for the beauty of

its

courtyards,

its graceful street arcades,

and its artistic treatment of

brick and terra-

cotta

(P.

Bevilacqua,

P.

Fava, at

Bologna; P.

Scrofa,

P.

Roverella, at

Ferrara). About

the

same time palaces with

interior arcades and details in the new

style were erected

in

Verona, Vicenza, Mantua, and other

cities.

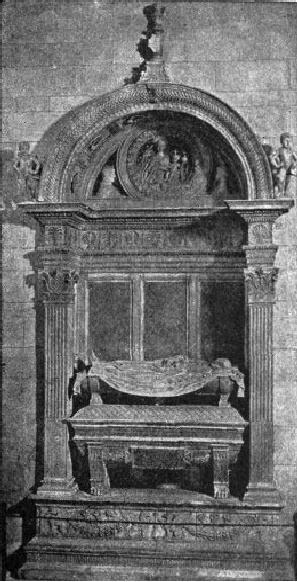

FIG.

164.--TOMB OF PIETRO DI NOCETO,

LUCCA.

VENICE.

In this city

of merchant princes and a wealthy

bourgeoisie, the

architecture

of

the Renaissance took on a new aspect of

splendor and display. It was

late in

appearing,

the Gothic style with its

tinge of Byzantine decorative

traditions having

here

developed into a style well suited to the

needs of a rich and relatively

tranquil

community.

These traditions the architects of the

new style appropriated in a

measure,

as in the marble incrustations of the

exquisite little church of S.

M. dei

Miracoli

(148089),

and the fa�ade of the Scuola

di S. Marco (14851533),

both

by

Pietro

Lombardo.

Nowhere else, unless on the

contemporary fa�ade of the

Certosa

at

Pavia, were marble inlays

and delicate carving, combined with a

framework of thin

pilasters,

finely profiled entablatures and arched

pediments, so lavishly

bestowed

upon

the street fronts of churches and

palaces. The family of the Lombardi

(Martino,

his

sons Moro and Pietro, and grandsons

Antonio and Tullio), with Ant.

Bregno and

Bart.

Buon,

were the leaders in the architectural

Renaissance of this period, and to

them

Venice owes her choicest

masterpieces in the new style. Its first

appearance is

noted

in the later portions of the church of

S.

Zaccaria (14561515),

partly Gothic

internally,

with a fa�ade whose semicircular

pediment and small decorative

arcades

show

a somewhat timid but interesting

application of classic details. In this

church,

and

still more so in S. Giobbe (145193)

and the Miracoli above mentioned,

the

decorative

element predominates throughout. It is

hard to imagine details

more

graceful

in design, more effective in the

swing of their movement, or more

delicate in

execution

than the mouldings, reliefs, wreaths,

scrolls, and capitals one

encounters in

these

buildings. Yet in structural interest, in

scale and breadth of planning,

these

early

Renaissance Venetian buildings hold a

relatively inferior rank.

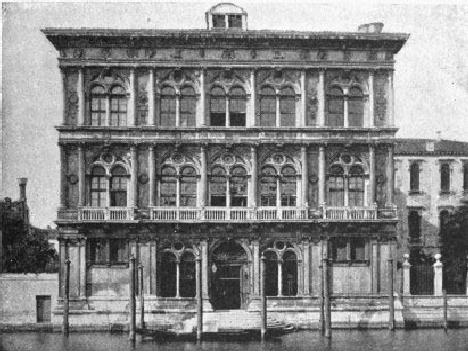

FIG.

165.--VENDRAMINI PALACE,

VENICE.

PALACES.

The

great Court

of the

Doge's

Palace,

begun 1483 by Ant.

Rizzio,

belongs

only in part to the first period. It

shows, however, the lack of

constructive

principle

and of largeness of composition just

mentioned, but its decorative

effect

and

picturesque variety elicit

almost universal admiration.

Like the neighboring

fa�ade

of St. Mark's, it violates nearly

every principle of correct

composition, and yet

in

a measure atones for this capital

defect by its charm of

detail. Far more

satisfactory

from the purely architectural point of view is the

fa�ade of the

P.

Vendramini (Vendramin-Calergi),

by Pietro Lombardo (1481). The simple,

stately

lines

of its composition, the dignity of

its broad arched and

mullioned windows,

separated

by engaged columns--the earliest

example in Venice of this feature,

and

one

of the earliest in Italy--its well-proportioned

basement and upper

stories,

crowned

by an adequate but somewhat heavy

entablature, make this one of the

finest

palaces

in Italy (Fig. 165) It established a type of

large-windowed, vigorously

modelled

fa�ades which later architects

developed, but hardly surpassed. In

the

smaller

contemporary, P. Dario, another type

appears, better suited for

small

buildings,

depending for effect mainly upon

well-ordered openings and

incrusted

panelling

of colored marble.

ROME.

Internal

disorders and the long exile of the

popes had by the end of the

fourteenth

century reduced Rome to utter

insignificance. Not until the second half

of

the

fifteenth century did returning

prosperity and wealth afford the

Renaissance its

opportunity

in the Eternal City. Pope Nicholas V.

had, indeed, begun the

rebuilding

of

St. Peter's from designs by B.

Rossellini, in 1450, but the project

lapsed shortly

after

with the death of the pope. The earliest

Renaissance building in Rome

was the

P.

di Venezia,

begun in 1455, together with the

adjoining porch of S. Marco. In

this

palace

and the adjoining unfinished Palazzetto

we find the influence of the old

Roman

monuments clearly manifested in the court

arcades, built like those of

the

Colosseum,

with superposed stages of massive

piers and engaged columns

carrying

entablatures.

The proportions are awkward, the

details coarse; but the spirit

of

Roman

classicism is here seen in the

germ. The exterior of this palace

is, however,

still

Gothic in spirit. The architects

are unknown; Giuliano

da Majano (145290),

Giacomo

di Pietrasanta, and

Meo

del Caprino (14301501)

are known to have

worked

upon it, but it is not certain in what

capacity.

The

new style, reaching, and in time

overcoming, the conservatism of the

Church,

overthrew

the old basilican traditions. In

S.

Agostino (147983),

by Pietrasanta,

and

S.

M. del Popolo, by

Pintelli (?), piers with

pilasters or half-columns and

massive

arches

separate the aisles, and the crossing is

crowned with a dome. To the

same

period

belong the Sistine chapel and

parts of the Vatican palace, but the

interest of

these

lies rather in their later

decorations than in their somewhat

scanty architectural

merit.

The

architectural renewal of Rome, thus

begun, reached its

culmination in the

following

period.

OTHER

MONUMENTS. The

complete enumeration of even the

most important Early

Renaissance

monuments of Italy is impossible within our

limits. Two or three only

can

here be singled out as suggesting

types. Among town halls of this

period the first

place

belongs to the P.

del Consiglio at

Verona, by Fra

Giocondo (14351515).

In

this

beautiful edifice the fa�ade

consists of a light and graceful arcade

supporting a

wall

pierced with four windows, and covered

with elaborate frescoed

arabesques

(recently

restored). Its unfortunate division by

pilasters into four bays, with a pier

in

the

centre, is a blemish avoided in the

contemporary P.

del Consiglio at

Padua. The

Ducal

Palace at Urbino, by

Luciano

da Laurano (1468), is

noteworthy for its fine

arcaded

court, and was highly famed in

its day. At Brescia S.

M. dei Miracoli is

a

remarkable

example of a cruciform domical church

dating from the close of this

period,

and is especially celebrated for the

exuberant decoration of its

porch and its

elaborate

detail. Few campaniles were

built in this period; the best of them

are at

Venice.

Naples possesses several

interesting Early Renaissance

monuments, chief

among

which are the Porta

Capuana (1484), by

Giul.

da Majano, the

triumphal Arch

of

Alphonso of

Arragon, by Pietro

di Martino, and the

P.

Gravina, by

Gab.

d'Agnolo.

Naples

is also very rich in minor works of the

early Renaissance, in which it

ranks

with

Florence, Venice, and

Rome.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.