|

CHAPTER

XIX.

GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED; As before, Corroyer,

Reber. Also, Cummings,

A

History of

Architecture

in Italy. De

Fleury, La

Toscane au moyen �ge.

Gruner, The

Terra Cotta

Architecture

of Northern Italy.

Mothes, Die

Baukunst des Mittelalters in

Italien.

Norton,

Historical

Studies of Church Building in

the Middle Ages.

Osten, Bauwerke

der

Lombardei.

Street, Brick

and Marble Architecture of

Italy.

Willis, Remarks

on the

Architecture

of the Middle Ages,

especially of Italy.

GENERAL

CHARACTER. The

various Romanesque styles which had grown

up in

Italy

before 1200 lacked that unity of

principle out of which alone a new

and

homogeneous

national style could have

been evolved. Each province

practised its

own

style and methods of building,

long after the Romanesque had

given place to the

Gothic

in Western Europe. The Italians

were better decorators than

builders, and

cared

little for Gothic structural principles.

Mosaic and carving, sumptuous

altars

and

tombs, veneerings and inlays of

colored marble, broad flat

surfaces to be covered

with

painting and ornament--to secure these

they were content to build crudely,

to

tie

their insufficiently buttressed vaults

with unsightly iron tie-rods, and to

make

their

church fa�ades mere screen-walls, in form

wholly unrelated to the buildings

behind

them.

When,

therefore, under foreign influences

pointed arches, tracery,

clustered shafts,

crockets

and finials came into use, it

was merely as an imported

fashion. Even when

foreign

architects (usually Germans)

were employed, the composition, and in

large

measure

the details, were still Italian and

provincial. The church of St. Francis

at

Assisi

(122853, by Jacobus

of Meruan, a

German, superseded later by an

Italian,

Campello),

and the cathedral of Milan (begun 1389,

perhaps by Henry

of Gmund),

are

conspicuous illustrations of this.

Rome built basilicas all through the

Middle

Ages.

Tuscany continued to prefer flat

walls veneered with marble to the

broken

surfaces

and deep buttresses of France and

Germany. Venice developed a

Gothic

style

of fa�ade-design wholly her own. Nowhere but in Italy

could two such utterly

diverse

structures as the Certosa at Pavia and

the cathedral at Milan have

been

erected

at the same time.

CLIMATE

AND TRADITION. Two

further causes militated

against the

domestication

of Gothic art in Italy. The first was the

brilliant atmosphere, which

made

the vast traceried windows of

Gothic design, and its

suppression of the wall-

surfaces,

wholly undesirable. Cool, dim interiors,

thick walls, small windows and

the

exclusion

of sunlight, all necessary to Italian

comfort, were incompatible with

Gothic

ideals

and methods. The second obstacle

was the persistence of classic

traditions of

form,

both in construction and decoration. The

spaciousness and breadth of

interior

planning

which characterized Roman design, and

its amplitude of scale in

every

feature,

seem never to have lost

their hold on the Italians. The narrow lofty

aisles,

multiplied

supports and minute detail of the Gothic

style were repugnant to

the

classic

predilections of the Italian builders.

The Roman acanthus and

Corinthian

capital

were constantly imitated in their

Gothic buildings, and the round

arch

continued

all through the Middle Ages to be used in

conjunction with the pointed

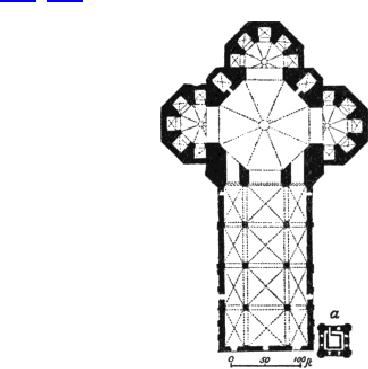

FIG.

147.--DUOMO AT FLORENCE. PLAN.

a,

Campanile.

EARLY

BUILDINGS. It is hard to

determine how and by whom Gothic forms

were

first

introduced into Italy, but it was most

probably through the agency of the

monastic

orders. Cistercian churches

like that at Chiaravalle near Milan

(120821),

and

most of those erected by the

mendicant orders of the Franciscans

(founded

1210)

and Dominicans (1216), were built with

ribbed vaults and pointed

arches.

The

example set by these orders

contributed greatly to the general

adoption of the

foreign

style. S.

Francesco at

Assisi,

already mentioned, was the

first completely

Gothic

Franciscan church, although

S.

Francesco at

Bologna,

begun a few years

later,

was finished a little earlier. The

Dominican church of SS.

Giovanni e Paolo

and

the great Franciscan church of Sta.

Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, both at

Venice,

were

built a little later. Sta.

Maria Novella at

Florence (1278), and Sta.

Maria sopra

Minerva

at

Rome (1280), both by the brothers

Sisto

and

Ristoro, and

S.

Anastasia at

Verona

(1261) are the masterpieces of the

Dominican builders. S.

Andrea at

Vercelli

in

North Italy, begun in 1219 under a foreign

architect, is an isolated early

example

of

lay Gothic work. Though somewhat English

in its plan, and (unlike most

Italian

churches)

provided with two western spires in the

English manner, it is in all other

respects

thoroughly Italian in aspect. The church at

Asti, begun in 1229,

suggests

German

models by its high side

walls and narrow windows.

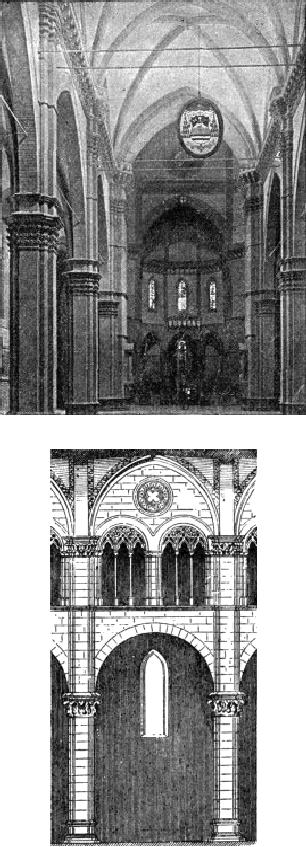

FIG.

148.--NAVE OF DUOMO AT FLORENCE.

FIG.

149.--ONE BAY, NAVE OF CATHEDRAL OF SAN

MARTINO, LUCCA.

CATHEDRALS.

The

greatest monuments of Italian Gothic

design are the

cathedrals,

in

which, even more than was the

case in France, the highly developed

civic pride of

the

municipalities expressed itself.

Chief among these half

civic, half religious

monuments

are the cathedrals of Sienna

(begun

in 1243), Arezzo

(1278),

Orvieto

(1290),

Florence

(the

Duomo,

Sta. Maria del Fiore, begun

1294 by Arnolfo di

Cambio),

Lucca

(S.

Martino, 1350), Milan

(13891418),

and S.

Petronio at

Bologna

(1390).

They are all of imposing size; Milan is

the largest of all Gothic

cathedrals

except

Seville. S. Petronio was

planned to be 600 feet long, the

present structure

with

its three broad aisles and

flanking chapels being

merely the nave of the

intended

edifice.

The Duomo at Florence (Fig. 147) is 500

feet long and covers

82,000

square

feet, while the octagon at the crossing

is 143 feet in diameter. The effect

of

these

colossal dimensions is,

however, as in a number of these large

Italian interiors,

singularly

belittled by the bareness of the walls,

by the great size of the

constituent

parts

of the composition, and by the lack of

architectural subdivisions and

multiplied

detail

to serve as a scale by which to gauge the

scale of the ensemble.

INTERIOR

TREATMENT. It

was doubtless intended to

cover these large

unbroken

wall-surfaces

and the vast expanse of the vaults

over naves of extraordinary

breadth,

with

paintings and color decoration.

This would have remedied their

present

nakedness

and lack of interest, but it was only in

a very few instances carried out.

The

double church of S. Francesco at Assisi,

decorated by Cimabue, Giotto,

and

other

early Tuscan painters, the

Arena Chapel at Padua,

painted by Giotto, the

Spanish

Chapel of S. M.

Novella, Florence, and the east

end of S. Croce,

Florence,

are

illustrations of the splendor of effect

possible by this method of decoration.

The

bareness

of effect in other, unpainted interiors

was emphasized by the plainness

of

the

vaults destitute of minor ribs. The

transverse ribs were usually

broad arches with

flat

soffits, and the vaulting was

often sprung from so low a point as to

leave no

room

for a triforium. Mere bull's-eyes often

served for clearstory windows, as

in

S.

Anastasia at Verona, S. Petronio at

Bologna, and the Florentine Duomo.

The

cathedral

of S.

Martino at

Lucca (Fig. 149) is one of the

most complete and

elegant

of

Italian Gothic interiors, having a

genuine triforium with traceried arches.

Even

here,

however, there are round

arches without mouldings, flat pilasters,

broad

transverse

ribs recalling Roman arches,

and insignificant bull's-eyes in the

clearstory.

The

failure to produce adequate

results of scale in the interiors of the

larger Italian

churches,

has been already alluded to.

It is strikingly exemplified in the Duomo

at

Florence,

the nave of which is 72 feet wide, with

four pier-arches each over 55

feet

in

span. The immense vault, in square

bays, starts from the level of the

tops of these

arches.

The interior (Fig. 148) is singularly

naked and cold, giving no

conception of

its

vast dimensions. The colossal

dome is an early work of the Renaissance.

It is not

known

how Fr.

Talenti, who in 1357

enlarged and vaulted the nave and

planned the

east

end, proposed to cover the

great octagon. The east end

is the most effective part

of

the design both internally and

externally, owing to the relatively

moderate scale of

the

15 chapels which surround the apsidal

arms of the cross. In S. Petronio

at

Bologna,

begun 1390 by Master

Antonio, the

scale is better handled. The

nave, 300

feet

long, is divided into six

bays, each embracing two

side chapels. It is 46 feet

wide

and

132 feet high, proportions which

approximate those of the French

cathedrals,

and

produce an impression of size

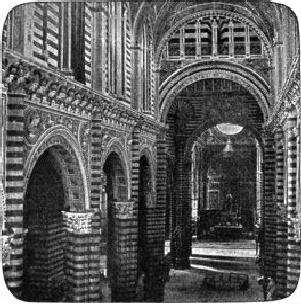

somewhat unusual in Italian churches.

Orvieto

has

internally

little that suggests Gothic architecture;

like many Franciscan and

Dominican

churches it is really a timber-roofed

basilica with a few pointed

windows.

The

mixed Gothic and Romanesque

interior of Sienna

Cathedral (Fig.

150), with its

round

arches and six-sided dome,

unsymmetrically placed over the

crossing, is one of

the

most impressive creations of Italian

medi�val art. Alternate courses of

black and

white

marble add richness but not

repose to the effect of this interior:

the same is

true

of Orvieto, and of some other

churches. The basement baptistery of

S.

Giovanni,

under

the east end of Sienna

Cathedral, is much more purely Gothic in

detail.

FIG.

150.--INTERIOR OF SIENNA

CATHEDRAL.

In

these, and indeed in most Italian

interiors, the main interest centres

less in the

excellence

of the composition than in the accessories of

pavements, pulpits,

choir-

stalls,

and sepulchral monuments. In these the

decorative fancy and skill of

the

Italians

found unrestrained exercise, and produced

works of surpassing interest

and

merit.

EXTERNAL

DESIGN. The

greatest possible disparity

generally exists between

the

sides

and west fronts of the Italian churches.

With few exceptions the flanks

present

nothing

like the variety of sky-line and of light

and shade customary in northern

and

western

lands. The side walls are

high and flat, plain, or striped with

black and

white

masonry (Sienna, Orvieto), or

veneered with marble (Duomo at

Florence) or

decorated

with surface-ornament of thin pilasters and

arcades (Lucca). The

clearstory

is

low; the roof low--pitched and hardly visible from

below. Color, rather

than

structural

richness, is generally sought for: Milan

Cathedral is almost the only

exception,

and goes to the other extreme, with

its seemingly countless

buttresses,

pinnacles

and statues.

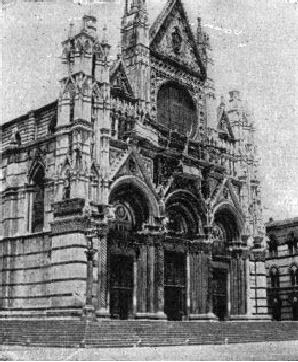

The

fa�ades, on the other hand, were

treated as independent

decorative

compositions,

and were in many cases remarkably

beautiful works, though

having

little

or no organic relation to the main

structure. The most celebrated

are those of

Sienna

(cathedral

begun 1243; fa�ade 1284 by Giovanni

Pisano;

Fig. 151) and

Orvieto

(begun

1290 by Lorenzo

Maitani;

fa�ade 1310). Both of these

are

sumptuous

polychromatic compositions in marble,

designed on somewhat

similar

lines,

with three high gables fronting the

three aisles, with deeply

recessed portals,

pinnacled

turrets flanking nave and

aisles, and a central circular window.

That of

Orvieto

is furthermore embellished with mosaic

pictures, and is the more brilliant

in

color

of the two. The medi�val fa�ades of the

Florentine Gothic churches

were never

completed;

but the elegance of the panelling and of the

tracery with twisted shafts

in

the

flanks of the cathedral, and the florid

beauty of its side doorways

(late 14th

century)

would doubtless if realized with equal

success on the fa�ades,

have

produced

strikingly beautiful results. The

modern fa�ade of the Duomo, by the

late

De

Fabris (1887) is a

correct if not highly imaginative version

of the style so applied.

The

front of Milan cathedral (soon to be

replaced by a new fa�ade), shows a

mixture

of

Gothic and Renaissance forms.

Ferrara

Cathedral,

although internally

transformed

in

the last century, retains its

fine 13th-century three-gabled and

arcaded screen

front;

one of the most Gothic in

spirit of all Italian fa�ades. The

Cathedral

of

Genoa

presents

Gothic windows and deeply

recessed portals in a fa�ade built in

black and

white

bands, like Sienna cathedral

and many churches in Pistoia and

Pisa.

FIG.

151.--FA�ADE OF SIENNA

CATHEDRAL.

Externally

the most important feature

was frequently a cupola or

dome over the

crossing.

That of Sienna has already

been mentioned; that of Milan is a

sumptuous

many-pinnacled

structure terminating in a spire 300

feet high. The Certosa

at

Pavia

(Fig.

152) and the earlier Carthusian church of

Chiaravalle have internal

cupolas or

domes

covered externally by many-storied

structures ending in a tower

dominating

the

whole edifice. These two churches,

like many others in Lombardy, the

�milia

and

Venetia, are built of brick,

moulded terra-cotta being

effectively used for the

cornices,

string-courses, jambs and ornaments of

the exterior. The Certosa at Pavia

is

contemporary

with the cathedral of Milan, to which it offers a

surprising contrast,

both

in style and material. It is wholly built of

brick and terra-cotta, and,

save for its

ribbed

vaulting, possesses hardly a single

Gothic feature or detail. Its

arches,

mouldings,

and cloisters suggest both the Romanesque

and the Renaissance styles by

their

semi-classic character.

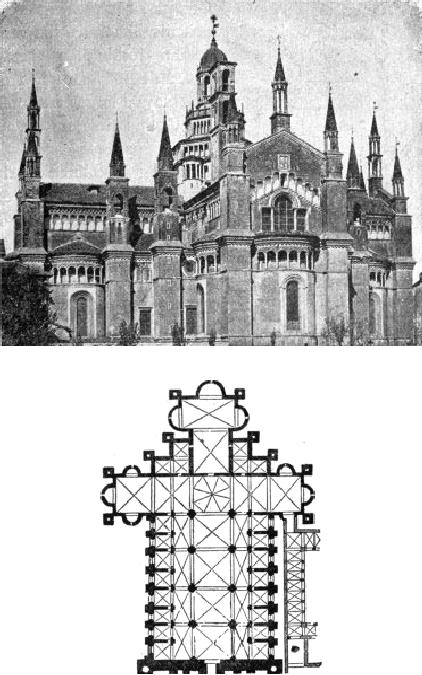

FIG.

152.--EXTERIOR OF THE CERTOSA,

PAVIA.

FIG.

153.--PLAN OF CERTOSA AT PAVIA.

PLANS.

The

wide diversity of local

styles in Italian architecture

appears in the plans

as

strikingly as in the details In general

one notes a love of

spaciousness which

expresses

itself in a sometimes disproportionate

breadth, and in the wide spacing

of

the

piers. The polygonal chevet with

its radial chapels is but

rarely seen; S.

Lorenzo

at

Naples, Sta. Maria dei Servi

and S. Francesco at Bologna are

among the most

important

examples. More frequently the chapels

form a range along the east

side of

the

transepts, especially in the Franciscan

churches, which otherwise retain

many

basilican

features. A comparison of the plans of S.

Andrea at Vercelli, the Duomo at

Florence,

the cathedrals of Sienna and Milan, S.

Petronio at Bologna and the

Certosa

at

Pavia (Fig. 153), sufficiently

illustrates the variety of Italian Gothic

plan-types.

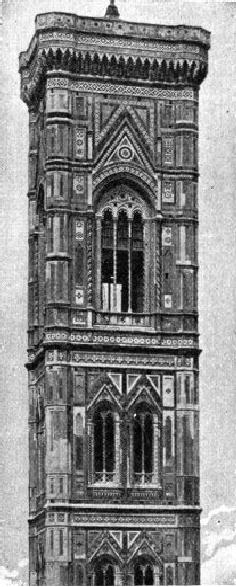

FIG.

154.--UPPER PART OF CAMPANILE,

FLORENCE.

ORNAMENT.

Applied

decoration plays a large part in all

Italian Gothic designs.

Inlaid

and mosaic patterns and panelled

veneering in colored marble

are essential

features

of the exterior decoration of most

Italian churches. Florence

offers a fine

example

of this treatment in the Duomo, and in its

accompanying Campanile

or

bell-

tower,

designed by Giotto

(1335), and

completed by Gaddi

and

Talenti.

This

beautiful

tower is an epitome of Italian Gothic

art. Its inlays, mosaics, and

veneering

are

treated with consummate elegance, and

combined with incrusted reliefs of

great

beauty.

The tracery of this monument and of the side

windows of the adjoining

cathedral

is lighter and more graceful than is

common in Italy. Its beauty

consists,

however,

less in movement of line than in

richness and elegance of carved and

inlaid

ornament.

In the Or

San Michele--a

combined chapel and granary in

Florence dating

from

1330--the tracery is far less light and

open. In general, except in

churches like

the

Cathedral of Milan, built under German

influences, the tracery in

secular

monuments

is more successful than in ecclesiastical

structures. Venice developed

the

designing

of tracery to greater perfection in her

palaces than any other Italian

city

(see

below).

MINOR

WORKS. Italian

Gothic art found freer expression in

semi-decorative works,

like

tombs, altars and votive

chapels, than in more monumental

structures. The

fourteenth

century was particularly rich in canopy

tombs, mostly in churches, though

some

were erected in the open air,

like the celebrated Tombs

of the Scaligers in

Verona

(13291380). Many of those in churches in and

near Rome, and others

in

south

Italy, are especially rich in inlay of

opus

Alexandrinum upon their

twisted

columns

and panelled sarcophagi. The family of the

Cosmati

acquired

great fame for

work

of this kind during the thirteenth

century.

The

little marble chapel of Sta.

Maria della Spina, on the Arno,

at Pisa, is an

instance

of the successful decorative use of

Gothic forms in minor

buildings.

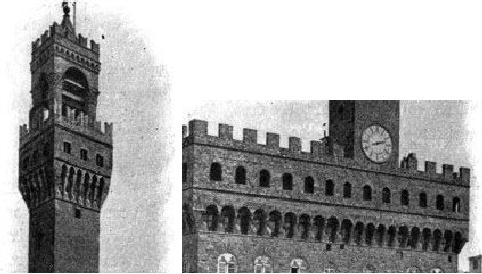

FIG.

155.--UPPER PART OF

PALAZZO

VECCHIO, FLORENCE.

TOWERS.

The

Italians always preferred the

square tower to the spire, and in

most

cases

treated it as an independent campanile.

Following Early Christian

and

Romanesque

traditions, these square

towers were usually built with

plain sides

unbroken

by buttresses, and terminated in a flat

roof or a low and inconspicuous

cone

or pyramid. The Campanile at Florence

already mentioned is by far the

most

beautiful

of these designs (Fig. 154). The

campaniles of Sienna, Lucca, and

Pistoia

are

built in alternate white and black

courses, like the adjoining

cathedrals. Verona

and

Mantua have towers with octagonal

lanterns. In general, these

Gothic towers

differ

from the earlier Romanesque models only

in the forms of their openings.

Though

dignified in their simplicity and size,

and usually well proportioned,

they

lack

the beauty and interest of the French,

English, and German steeples and

towers.

SECULAR

MONUMENTS. In

their public halls, open

loggias, and

domestic

architecture

the Italians were able to

develop the application of Gothic

forms with

greater

freedom than in their church-building,

because unfettered by

traditional

methods

of design. The early and vigorous growth

of municipal and popular

institutions

led, as in the Netherlands, to the

building of two classes of public

halls--

the

town hall proper or Podest�, and the

council hall, variously called

Palazzo

Communale,

Pubblico, or

del

Consiglio. The town

halls, as the seat of authority,

usually

have a severe and fortress-like

character; the Palazzo

Vecchio at

Florence is

the

most important example (1298, by

Arnolfo di Cambio; Fig. 155). It is

especially

remarkable

for its tower, which, rising 308 feet in

the air, overhangs the street

nearly

6 feet, its front wall resting on the

face of the powerfully corbelled cornice

of

the

palace. The court and most of the

interior were remodelled in the

sixteenth

century.

At Sienna is a somewhat similar

structure in brick, the Palazzo

Pubblico.

At

Pistoia

the Podest� and the Communal Palace

stand opposite each other;

in both of

these

the courtyards still retain their

original aspect. At Perugia,

Bologna, and

Viterbo

are others of some

importance; while in Lombardy, Bergamo,

Como,

Cremona,

Piacenza and other towns possess

smaller halls with open

arcades below,

of

a more elegant and pleasing

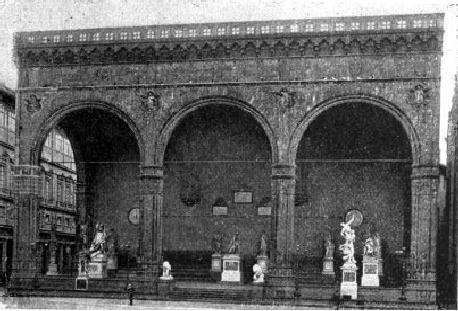

aspect. More successful still

are the open loggias

or

tribunes

erected for the gatherings of public

bodies. The Loggia

dei Lanzi at

Florence

(1376,

by Benci

di Cione and

Simone

di Talenti) is the

largest and most famous

of

these

open vaulted halls, of which

several exist in Florence and

Sienna. Gothic only

in

their minor details, they are Romanesque

or semi-classic in their broad

round

arches

and strong horizontal lines and

cornices (Fig. 156).

PALACES

AND HOUSES: VENICE. The northern

cities, especially Pisa,

Florence,

Sienna,

Bologna, and Venice, are rich in

medi�val public and private

palaces and

dwellings

in brick or marble, in which pointed

windows and open arcades are

used

with

excellent effect. In Bologna and

Sienna brick is used, in

conjunction with details

executed

in moulded terra-cotta, in a highly

artistic and effective way.

Viterbo,

nearer

Rome, also possesses many

interesting houses with street

arcades and open

stairways

or stoops leading to the main

entrance.

The

security and prosperity of Venice in the

Middle Ages, and the ever

present

influence

of the sun-loving East, made the

massive and fortress-like architecture

of

the

inland cities unnecessary. Abundant

openings, large windows full of

tracery of

great

lightness and elegance, projecting

balconies and the freest use of

marble

veneering

and inlay--a survival of Byzantine

traditions of the 12th century--give

to

the

Venetian houses and palaces an

air of gayety and elegance found

nowhere else.

While

there are few Gothic

churches of importance in Venice, the

number of

medi�val

houses and palaces is very large.

Chief among these is the

Doge's

Palace

(Fig.

157), adjoining the church of St. Mark. The

two-storied arcades of the west

and

south

fronts date from 1354, and originally

stood out from the main edifice,

which

was

widened in the next century, when the present

somewhat heavy walls, laid

up in

red,

white and black marble in a species of

quarry-pattern, were built over

the

arcades.

These arcades are beautiful

designs, combining massive

strength and grace

in

a manner quite foreign to

Western Gothic ideas.

Lighter and more ornate is the

Ca

d'Oro, on the Grand

Canal; while the Foscari,

Contarini-Fasan, Cavalli, and

Pisani

palaces,

among many others, are

admirable examples of the style. In

most of these a

traceried

loggia occupies the central

part, flanked by walls

incrusted with marble and

pierced

by Gothic windows with carved mouldings,

borders, and balconies. The

Venetian

Gothic owes its success

largely to the absence of structural

difficulties to

interfere

with the purely decorative development of

Gothic details.

FIG.

156.--LOGGIA DEI LANZI,

FLORENCE.

MONUMENTS.

13th

Century: Cistercian abbeys

Fossanova and Casamari,

cir.

1208; S.

Andrea,

Vercelli,

1209; S. Francesco, Assisi, 122853;

Church at Asti, 1229; Sienna

C., 124359

(cupola

125964; fa�ade 1284); S. M. Gloriosa

dei Frari, Venice, 125080

(finished 1388);

Sta.

Chiara, Assisi, 1250; Sta.

Trinit�, Florence, 1250; S. Antonio,

Padua, begun 1256;

SS.

Giovanni

e Paolo, Venice, 1260 (?)-1400;

Sta. Anastasia, Verona, 1261;

Naples C., 12721314

(fa�ade

1299; portal 1407; much altered

later); S. Lorenzo, Naples, 1275;

Campo Santo, Pisa,

127883;

Arezzo C., 1278; S. M. Novella,

Florence, 1278; S. Eustorgio, Milan,

1278; S. M.

sopra

Minerva, Rome, 1280; Orvieto

C., 1290 (fa�ade 1310; roof

1330); Sta. Croce,

Florence,

1294

(fa�ade 1863); S. M. del

Fiore, or C., Florence, 12941310

(enlarged 1357; E. end 1366;

dome

142064; fa�ade 1887); S. Francesco,

Bologna.--14th century: Genoa

C., early 14th

century;

S. Francesco, Sienna, 1310; San

Domenico, Sienna, about same

date; S. Giovanni in

Fonte,

Sienna, 1317; S. M. della Spina,

Pisa, 1323; Campanile, Florence, 1335; Or

San

Michele,

Florence, 1337; Milan C., 1386 (cupola

16th century; fa�ade 16th-19th

century; new

fa�ade

building 1895); S. Petronio,

Bologna, 1390; Certosa, Pavia, 1396

(choir, transepts,

cupola,

cloisters, 15th and 16th centuries);

Como C., 1396 (choir and

transepts 1513); Lucca

C.

(S.

Martino), Romanesque building

remodelled late in 14th century;

Verona C.; S. Fermo,

Maggiore;

S. Francesco, Pisa; S. Lorenzo,

Vicenza.--15th century: Perugia

C.; S. M. delle

Grazie,

Milan,

1470 (cupola and exterior E.

part later).

FIG.

157.--WEST FRONT VIEW OF

DOGE'S PALACE,

VENICE.

SECULAR BUILDINGS: Pal. Pubblico, Cremona,

1245; Pal. Podest� (Bargello),

Florence,

1255

(enlarged 133345); Pal. Pubblico,

Sienna, 12891305 (many later

alterations);

Pal.

Giureconsulti, Cremona, 1292; Broletto,

Monza, 1293; Loggia dei

Mercanti,

Bologna,

1294; Pal. Vecchio, Florence, 1298;

Broletto, Como; Pal. Ducale

(Doge's

Palace),

Venice, 131040 (great windows 1404;

extended 142338; courtyard 15th

and

16th

centuries); Loggia dei

Lanzi, Florence, 1335; Loggia

del Bigallo, 1337;

Broletto,

Bergamo,

14th century; Loggia dei

Nobili, Sienna, 1407; Pal.

Pubblico, Udine, 1457;

Loggia

dei Mercanti, Ancona; Pal.

del Governo, Bologna; Pal.

Pepoli, Bologna;

Palaces

Conte

Bardi, Davanzati, Capponi,

all at Florence; at Sienna,

Pal. Tolomei, 1205;

Pal.

Saracini,

Pal. Buonsignori; at Venice,

Pal. Contarini-Fasan, Cavalli,

Foscari, Pisani, and

many

others; others in Padua and

Vicenza.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.