|

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN |

| << GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS. >> |

CHAPTER

XVIII.

GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE

NETHERLANDS,

AND

SPAIN.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before,

Corroyer, Reber. Also,

Adler, Mittelalterliche

Backstein-Bauwerke

des preussischen Staates.

Essenwein (Hdbuch.

d. Arch.),

Die

romanische

und die gothische Baukunst;

der Wohnbau.

Hasak, Die

romanische und die

gothische

Baukunst; Kirchenbau;

Einzelheiten

des Kirchenbaues (both

in Hdbuch.

d.

Arch.).

Hase and others, Die

mittelalterlichen Baudenkm�ler

Niedersachsens.

Kallenbach,

Chronologie

der deutschen mittelalterlichen

Baukunst.

L�bke, Ecclesiastical

Art

in Germany during the Middle

Ages.

Redtenbacher, Leitfaden

zum Studium der

mittelalterlichen

Baukunst.

Street, Gothic

Architecture in Spain.

Uhde, Baudenkm�ler

in

Spanien.

Ungewitter, Lehrbuch

der gothischen

Constructionen.

Villa Amil, Hispania

Artistica

y Monumental.

EARLY

GOTHIC WORKS. The

Gothic architecture of Germany is

less interesting to

the

general student than that of France and

England, not only because

its

development

was less systematic and more

provincial, but also because it

produced

fewer

works of high intrinsic merit. The

introduction into Germany of the

pointed

style

was tardy, and its progress slow.

Romanesque architecture had

created

imposing

types of ecclesiastical architecture,

which the conservative Teutons

were

slow

to abandon. The result was a

half-century of transition and a mingling

of

Romanesque

and Gothic forms. St.

Castor, at Coblentz, built as late as

1208, is

wholly

Romanesque. Even when the pointed

arch and vault had finally come

into

general

use, the plan and the constructive system

still remained

predominantly

Romanesque.

The western apse and short

sanctuary of the earlier plans

were

retained.

There was no triforium, the clearstory

was insignificant, and the whole

aspect

low and massive. The Germans avoided, at

first, as did the English, the

constructive

audacities and difficulties of the French

Gothic, but showed less

of

invention

and grace than their English

neighbors. When, however, through

the

influence

of foreign models, especially of the

great French cathedrals, and

through

the

employment of foreign architects, the

Gothic styles were at last

thoroughly

domesticated,

a spirit of ostentation took the

place of the earlier

conservatism.

Technical

cleverness, exaggerated ingenuity of

detail, and constructive tours

de force

characterize

most of the German Gothic work of the

late fourteenth and of the

fifteenth

century. This is exemplified in the

slender mullions of Ulm, the lofty

and

complicated

spire of Strasburg, and the curious

traceries of churches and houses

in

Nuremberg.

PERIODS.

The

periods of German medi�val

architecture corresponded in

sequence,

though

not in date, with the movement elsewhere.

The maturing of the true Gothic

styles

was preceded by more than a

half-century of transition.

Chronologically the

periods

may be broadly stated as

follows:

THE TRANSITIONAL, 11701225.

THE EARLY POINTED, 12251275.

THE MIDDLE OR DECORATED, 12751350.

THE FLORID,

13501530.

These

divisions are, however, far

less clearly defined than in

France and England.

The

development of forms was

less logical and consequential, and

less uniform in the

different

provinces, than in those western

lands.

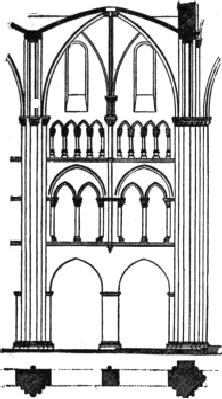

FIG.

139.--ONE BAY OF CATHEDRAL OF ST.

GEORGE, LIMBURG.

CONSTRUCTION.

As

already remarked, a tenacious hold of

Romanesque methods is

observable

in many German Gothic monuments.

Broad wall-surfaces with

small

windows

and a general massiveness and lowness of

proportions were long

preferred

to

the more slender and lofty forms of true

Gothic design. Square

vaulting-bays were

persistently

adhered to, covering two aisle-bays. The

six-part system was only

rarely

resorted

to, as at Schlettstadt, and in St. George

at Limburg-on-the-Lahn (Fig. 139).

The

ribbed vault was an imported

idea, and was never

systematically developed.

Under

the final dominance of French models in

the second half of the thirteenth

century,

vaulting in oblong bays

became more general, powerfully

influenced by

buildings

like Freiburg, Cologne,

Oppenheim, and Ratisbon cathedrals. In

the

fourteenth

century the growing taste for elaboration

and rich detail led to the

introduction

of multiplied decorative ribs.

These, however, did not come into

use, as

in

England, through a logical development of

constructive methods, but purely

as

decorative

features. The German multiple-ribbed

vaulting is, therefore, less

satisfying

than

the English, though often elegant.

Conspicuous examples of its

application are

found

in the cathedrals of Freiburg, Ulm,

Prague, and Vienna; in St.

Barbara at

Kuttenberg,

and many other important churches. But

with all the richness and

complexity

of these net-like vaults the

Germans developed nothing

like the fan-

vaulting

or chapter-house ceilings of

England.

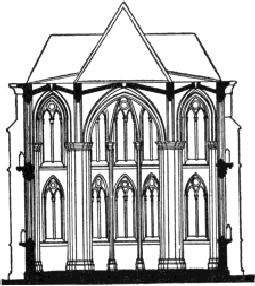

SIDE

AISLES. The

most notable structural

innovation of the Germans was

the

raising

of the side aisles to the same

height as the central aisle in a number

of

important

churches. They thus created a distinctly

new type, to which German

writers

have given the name of

hall-church. The

result of this innovation was

to

transform

completely the internal perspective of

the church, as well as its

structural

membering.

The clearstory disappeared; the central

aisle no longer dominated

the

interior;

the pier-arches and side-walls were

greatly increased in height, and

flying

buttresses

were no longer required. The whole

design appeared internally

more

spacious,

but lost greatly in variety and in

interest. The cathedral of St.

Stephen at

Vienna

is the most imposing instance of this

treatment, which first appeared in

the

church

of St. Elizabeth at Marburg (123583;

Fig. 140). St. Barbara at

Kuttenberg,

St.

Martin's at Landshut (1404), and the cathedral of

Munich are others

among

many

examples of this type.

FIG.

140.--SECTION OF ST. ELIZABETH,

MARBURG.

TOWERS

AND SPIRES. The

same fondness for spires which had

been displayed in

the

Rhenish Romanesque churches

produced in the Gothic period a number

of

strikingly

beautiful church steeples, in which

openwork tracery was

substituted for

the

solid stone pyramids of

earlier examples. The most

remarkable of these spires

are

those

of Freiburg (1300), Strasburg, and

Cologne cathedrals, of the church

at

Esslingen,

St. Martin's at Landshut, and the

cathedral of Vienna. In these

the

transition

from the simple square tower

below to the octagonal belfry and

spire is

generally

managed with skill. In the remarkable

tower of the cathedral at

Vienna

(1433)

the transition is too gradual, so that

the spire seems to start from the

ground

and

lacks the vigor and accent of a

simpler square lower

portion. The over-elaborate

spire

of Strasburg

(1429, by

Junckher of Cologne; lower

parts and fa�ade, 1277

1365,

by Erwin

von Steinbach and

his sons) reaches a height

of 468 feet; the spires

of

Cologne, completed in 1883 from the

original fourteenth-century drawings,

long

lost

but recovered by a happy accident,

are 500 feet high. The

spires of Ratisbon

and

Ulm

cathedrals

have also been recently

completed in the original

style.

DETAILS.

German

window tracery was best

where it most closely

followed French

patterns,

but it tended always towards the

faults of mechanical stiffness and

of

technical

display in over-slenderness of shafts and

mullions. The windows,

especially

in

the "hall-churches," were apt to be too

narrow for their height. In the

fifteenth

century

ingenuity of geometrical combinations

took the place of grace of

line, and

later

the tracery was often

tortured into a stone caricature of

rustic-work of

interlaced

and twisted boughs and twigs,

represented with all their bark and

knots

(branch-tracery). The

execution was far superior to the

design. The carving of

foliage

in

capitals, finials, etc.,

calls for no special mention for

its originality or its

departure

from

French types.

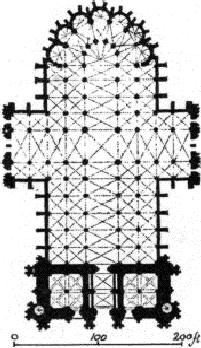

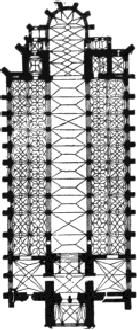

FIG.

141.--COLOGNE CATHEDRAL.

PLAN.

PLANS.

In

these there was more

variety than in any other part of Europe

except

Italy.

Some churches, like

Naumburg, retained the Romanesque

system of a second

western

apse and short choir. The

Cistercian churches generally had

square east

ends,

while the polygonal eastern apse without

ambulatory is seen in St.

Elizabeth at

Marburg,

the cathedrals of Ratisbon, Ulm and

Vienna, and many other churches.

The

introduction

of French ideas in the thirteenth

century led to the adoption in

a

number

of cases of the chevet with a single

ambulatory and a series of

radiating

apsidal

chapels. Magdeburg

cathedral

(120811) was the first erected on

this plan,

which

was later followed at

Altenburg, Cologne, Freiburg,

L�beck, Prague and

Zwettl,

in St. Francis at Salzburg and

some other churches. Side

chapels to nave or

choir

appear in the cathedrals of L�beck,

Munich, Oppenheim, Prague and

Zwettl.

Cologne

Cathedral, by far the

largest and most magnificent of all, is

completely

French

in plan, uniting in one design the

leading characteristics of the most

notable

French

churches (Fig. 141). It has

complete double aisles in both

nave and choir,

three-aisled

transepts, radial chevet-chapels and twin

western towers. The

ambulatory

is, however, single, and

there are no lateral

chapels. A typical

German

treatment

was the eastward termination of the

church by polygonal chapels, one

in

the

axis of each aisle, the

central one projecting

beyond its neighbors. Where

there

were

five aisles, as at Xanten, the

effect was particularly

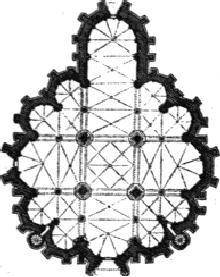

fine. The plan of the curious

polygonal

church of Our

Lady (Liebfrauenkirche;

122743) built on the site of the

ancient

circular baptistery at Treves, would

seem to have been produced

by doubling

such

an arrangement on either side of the

transverse axis (Fig.

142).

FIG.

142.--CHURCH OF OUR LADY,

TREVES.

HISTORICAL

DEVELOPMENT. The

so-called Golden

Portal of

Freiburg

in

the

Erzgebirge

is perhaps the first distinctively

Gothic work in Germany, dating

from

1190.

From that time on, Gothic

details appeared with increasing

frequency,

especially

in the Rhine provinces, as shown in many

transitional structures.

Gelnhausen

and

Aschaffenburg are early 13th-century

examples; pointed arches

and

vaults

appear in the Apostles' and St. Martin's

churches at Cologne; and the

great

church

of St.

Peter and St. Paul

at

Neuweiler in Alsace has an

almost purely Gothic

nave

of the same period. The churches of

Bamberg,

Fritzlar, and

Naumburg, and

in

Westphalia

those of M�nster

and

Osnabr�ck,

are important examples of

the

transition.

The French influence, especially the

Burgundian, appears as early as

1212

in

the cathedral of Magdeburg, imitating the

choir of Soissons, and in the

structural

design

of the Liebfrauenkirche at Treves as

already mentioned; it reached

complete

ascendancy

in Alsace at Strasburg

(nave

124075), in Baden at Freiburg

(nave

1270)

and in Prussia at Cologne

(12481320).

Strasburg Cathedral is

especially

remarkable

for its fa�ade, the work of Erwin von

Steinbach and his sons

(1277

1346),

designed after French

models, and its north spire, built in the

fifteenth

century.

Cologne Cathedral, begun in 1248 by

Gerhard

of Riel in

imitation of the

newly

completed choir of Amiens,

was continued by Master

Arnold

and

his son John,

and

the choir was consecrated in 1322. The

nave and W. front were built during

the

first

half of the 14th century, though the towers were not

completed till 1883.

FIG.

143.--PLAN OF ULM CATHEDRAL.

In

spite of its vast size and

slow construction, it is in style the

most uniform of all

great

Gothic cathedrals, as it is the most

lofty (excepting the choir of Beauvais)

and

the

largest excepting Milan and Seville.

Unfortunately its details, though pure

and

correct,

are singularly dry and mechanical, while

its very uniformity deprives it of

the

picturesque

and varied charm which results from a

mixture of styles recording the

labors

of successive generations. The same

criticism may be raised against the

late

cathedral

of Ulm

(choir,

13771449; nave, 1477; Fig. 143). The

Cologne influence

is

observable in the widely separated

cathedrals of Utrecht in the Netherlands,

Metz

in

the W., Minden and Halberstadt

(begun

1250; mainly built after 1327) in

Saxony,

and in the S. in the church of St.

Catherine at

Oppenheim. To the E. and S.,

in

the cathedrals of Prague

(Bohemia)

by Matthew

of Arras (134452)

and Ratisbon

(or

Regensburg, 1275) the French influence

predominates, at least in the details

and

construction.

The last-named is one of the most

dignified and beautiful of

German

Gothic

churches--German in plan, French in

execution. The French influence

also

manifests

itself in the details of many of the

peculiarly German churches with

aisles

of

equal height.

More

peculiarly German are the

brick churches of North Germany, where

stone was

almost

wholly lacking. In these, flat walls,

square towers, and decoration by

colored

tiles

and bricks are characteristic, as at

Brandenburg (St. Godehard and

St.

Catherine,

13461400), at Prentzlau,

T�ngerm�nde, K�nigsberg, &c.

L�beck

possesses

notable monuments of brick

architecture in the churches of St.

Mary and

St.

Catherine, both much alike in plan and in the flat and

barren simplicity of their

exteriors.

St.

Martin's at

Landshut

in the

South is also a notable

brick church.

LATE

GOTHIC. As in

France and England, the fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries

were

mainly occupied with the completion of

existing churches, many of which, up

to

that

time, were still without

naves. The works of this period show the

exaggerated

attenuation

of detail already alluded to, though

their richness and elegance

sometimes

atone for their mechanical character. The

complicated ribbed vaults

of

this

period are among its

most striking features.

Spire-building was as general as

was

the

erection of central square

towers in England, during the

same period. To this

time

also belong the overloaded

traceries and minute detail of the

St.

Sebald and

St.

Lorenz

churches and of several secular

buildings at Nuremberg, the fa�ade

of

Chemnitz

Cathedral, and similar works. The

nave and tower of St.

Stephen at Vienna

(13591433),

the church of Sta. Maria in Gestade in the

same city, and the

cathedral

of Kaschau in Hungary, are Austrian

masterpieces of late Gothic

design.

SECULAR

BUILDINGS. Germany

possesses a number of important examples

of

secular

Gothic work, chiefly municipal

buildings (gates and town halls) and

castles.

The

first completely Gothic

castle or palace was not built until

1280, at Marienburg

(Prussia),

and was completed a century later. It

consists of two courts, the earlier

of

the

two forming a closed square and

containing the chapel and chapter-house

of the

Order

of the German knights. The later and

larger court is less regular,

its chief

feature

being the Great

Hall of the Order,

in two aisles. All the vaulting is of

the

richest

multiple-ribbed type. Other castles

are at Marienwerder, Heilsberg (1350)

in

E.

Prussia, Karlstein in Bohemia (1347), and

the Albrechtsburg

at

Meissen in Saxony

(147183).

Among

town halls, most of which date from the

fourteenth and fifteenth

centuries

may

be mentioned those of Ratisbon

(Regensburg), M�nster and

Hildesheim,

Halberstadt,

Brunswick,

L�beck, and Bremen--the last two of

brick. These, and the

city

gates, such as the Spahlenthor

at

Basle (Switzerland) and others at

L�beck and

Wismar,

are generally very picturesque

edifices. Many fine guildhalls

were also built

during

the last two centuries of the Gothic

style; and dwelling-houses of the

same

period,

of quaint and effective design, with

stepped or traceried gables, lofty

roofs,

openwork

balconies and corner turrets,

are to be found in many cities. Nuremberg

is

especially

rich in these.

THE

NETHERLANDS, as might be

expected from their position, underwent

the

influences

of both France and Germany. During the

thirteenth century, largely

through

the intimate monastic relations

between Tournay and Noyon, the

French

influence

became paramount in what is now Belgium,

while Holland remained more

strongly

German in style. Of the two countries

Belgium developed by far the

most

interesting

architecture. Some of its

cathedrals, notably those of Tournay,

Antwerp,

Brussels,

Malines (Mechlin), Mons and Louvain, rank

high among structures of

their

class,

both in scale and in artistic treatment.

The Flemish town halls and

guildhalls

merit

particular attention for their size and

richness, exemplifying in a worthy

manner

the wealth, prosperity, and independence

of the weavers and merchants of

Antwerp,

Ypres, Ghent (Gand), Louvain, and

other cities in the fifteenth

century.

CATHEDRALS

AND CHURCHES. The

earliest purely Gothic edifice in

Belgium was

the

choir of Ste.

Gudule (1225) at

Brussels, followed in 1242 by the choir

and

transepts

of Tournay,

designed with pointed vaults,

side chapels, and a

complete

chevet. The

transept-ends are round, as at Noyon. It

was surpassed in splendor

by

the

Cathedral

of

Antwerp

(13521422),

remarkable for its seven-aisled

nave and

narrow

transepts. It covers some 70,000

square feet, but its great

size is not as

effective

internally as it should be,

owing to the poverty of the details and

the lack of

finely

felt proportion in the various parts. The

late west front (14221518)

displays

the

florid taste of the wealthy Flemish

burgher population of that period, but is

so

rich

and elegant, especially its lofty and

slender north spire, that its

over-decoration

is

pardonable. The cathedral of St.

Rombaut at

Malines (choir, 1366; nave,

1454

64)

is a more satisfactory church, though

smaller and with its western

towers

incomplete.

The cathedral of Louvain

belongs

to the same period (13731433).

St.

Wandru

at Mons

(14501528) and St.

Jacques at

Li�ge (152258) are

interesting

parish

churches of the first rank, remarkable

especially for the use of color in

their

internal

decoration, for their late tracery and

ribbed vaulting, and for the absence

of

Renaissance

details at that late

period.

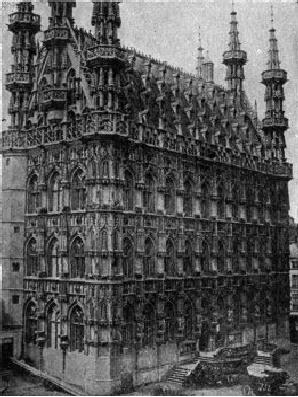

FIG.

144.--TOWN HALL, LOUVAIN.

TOWN

HALLS: GUILDHALLS. These

were really the most

characteristic Flemish

edifices,

and are in most cases the

most conspicuous monuments of

their respective

cities.

The Cloth

Hall of

Ypres

(1304) is the

earliest and most imposing

among

them;

similar halls were built not much

later at Bruges,

Louvain,

Malines

and

Ghent. The town

halls were mostly of later

date, the earliest being that of

Bruges

(1377).

The town halls of Brussels

with

its imposing and graceful tower, of

Louvain

(144863;

Fig. 144) and of Ouden�rde

(early

16th century) are

conspicuous

monuments

of this class.

In

general, the Gothic architecture of

Belgium presents the traits of a

borrowed style,

which

did not undergo at the hands of its

borrowers any radically novel

or

fundamental

development. The structural design is

usually lacking in vigor

and

organic

significance, but the details are

often graceful and well designed,

especially

on

the exterior. The tendency was

often towards over-elaboration,

particularly in the

later

works.

The

Gothic architecture of Holland

and of the

Scandinavian

countries

offers so little

that

is highly artistic or inspiring in

character, that space cannot well be

given in this

work,

even to an enumeration of its

chief monuments.

SPAIN

AND PORTUGAL. The

beginnings of Gothic architecture in

Spain followed

close

on the series of campaigns from 1217 to 1252, which

began the overthrow of

the

Moorish dominion. With the resulting

spirit of exultation and the wealth

accruing

from

booty, came a rapid development of

architecture, mainly under French

influence.

Gothic architecture was at this

date, under St. Louis,

producing in France

some

of its noblest works. The

great cathedrals of Toledo

and

Burgos,

begun

between

1220 and 1230, were the earliest purely

Gothic churches in Spain.

San

Vincente

at

Avila and the Old

Cathedral at

Salamanca, of somewhat earlier

date,

present

a mixture of round- and pointed-arched

forms, with the Romanesque

elements

predominant. Toledo

Cathedral,

planned in imitation of Notre

Dame and

Bourges,

but exceeding them in width, covers 75,000

square feet, and thus

ranks

among

the largest of European cathedrals.

Internally it is well proportioned and well

detailed,

recalling the early

French masterworks, but

its exterior is

less

commendable.

In

the contemporary cathedral of Burgos the

exterior is at least as interesting as

the

interior.

The west front, of German design,

suggests Cologne by its twin

openwork

spires

(Fig. 145); while the crossing is

embellished with a sumptuous dome

and

lantern

or cimborio,

added as late as 1567. The chapels at the

east end, especially

that

of the Condestabile (1487), are ornate to

the point of overloading, a fault to

which

late Spanish Gothic work is

peculiarly prone. Other

thirteenth-century

cathedrals

are those of Leon

(1260),

Valencia

(1262), and

Barcelona

(1298),

all

exhibiting

strongly the French influence in the

plan, vaulting, and vertical

proportions.

The models of Bourges and Paris with

their wide naves, lateral

chapels

and

semicircular chevets were

followed in the cathedral of Barcelona,

in a number of

fourteenth-century

churches both there and elsewhere, and in

the sixteenth-century

cathedral

of Segovia. In Sta. Maria del Pi at

Barcelona, in the collegiate church

at

Manresa,

and in the imposing nave of the Cathedral

of

Gerona

(1416,

added to

choir

of 1312, the latter by a Southern French

architect, Henri de Narbonne), the

influence

of Alby in southern France is

discernible. These are

one-aisled churches

with

internal buttresses separating the

lateral chapels. The nave of

Gerona is 73 feet

wide,

or double the average clear width of

French or English cathedral

naves. The

resulting

effect is not commensurate with the

actual dimensions, and shows

the

inappropriateness

of Gothic details for compositions so

Roman in breadth and

simplicity.

FIG.

145.--FA�ADE OF BURGOS

CATHEDRAL.

SEVILLE.

The

largest single edifice in

Spain, and the largest church built

during the

Middle

Ages in Europe, is the Cathedral

of Seville,

begun in 1401 on the site of a

Moorish

mosque. It covers 124,000 square

feet, measuring 415 � 298 feet, and

is

a

simple rectangle comprising

five aisles with lateral

chapels. The central aisle is

56

ft.

wide and 145 high; the side

aisles and chapels diminish

gradually in height, and

with

the uniform piers in six rows

produce an imposing effect, in

spite of the lack of

transepts

or chevet. The somewhat similar

New

Cathedral of

Salamanca (1510

1560)

shows the last struggles of the

Gothic style against the

incoming tide of the

Renaissance.

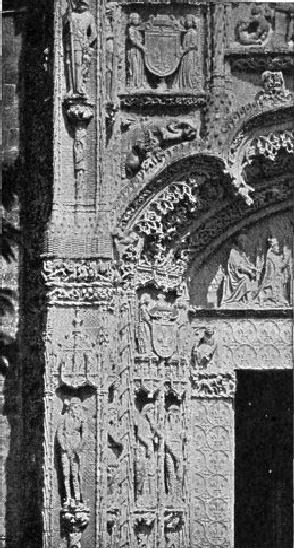

LATER

MONUMENTS. These

all partake of the over-decoration which

characterized

the

fifteenth century throughout Europe. In

Spain this decoration was

even less

constructive

in character, and more purely fanciful

and arbitrary, than in the

northern

lands; but this very rejection of all

constructive pretense gives it a

peculiar

charm

and goes far to excuse its

extravagance (Fig. 146). Decorative

vaulting-ribs

were

made to describe geometric

patterns of great elegance.

Some of the late

Gothic

vaults

by the very exuberance of imagination shown in

their designs, almost

disarm

criticism.

Instead of suppressing the walls as far

as possible, and emphasizing all

the

vertical

lines, as was done in France

and England, the later Gothic

architects of Spain

delighted

in broad wall-surfaces and multiplied

horizontal lines. Upon these

surfaces

they

lavished carving without restraint and

without any organic relation to

the

structure

of the building. The arcades of cloisters

and interior courts (patios)

were

formed

with arches of fantastic curves

resting on twisted columns; and

internal

chapels

in the cathedrals were covered with

minute carving of exquisite

workmanship,

but wholly irrational design. Probably

the influence of Moorish

decorative

art accounts in part for these

extravagances. The eastern chapels in

Burgos

cathedral,

the votive church of San

Juan de los Reyes at

Toledo and many portals of

churches,

convents and hospitals illustrate

these tendencies.

FIG.

146.--DETAIL, PORTAL S. GREGORIO,

VALLADOLID.

PORTUGAL

is an

almost unknown land architecturally. It

seems to have adopted

the

Gothic

styles very late in its

history. Two monuments, however,

are conspicuous, the

convent

churches of Batalha (13901520) and

Belem, both

marked by an extreme

overloading

of carved ornament. The Mausoleum

of King Manoel in the

rear of the

church

at Batalha is, however, a

noble creation, possibly by an

English master. It is a

polygonal

domed edifice, some 67 feet

in diameter, and well designed,

though

covered

with a too profuse and somewhat

mechanical decoration of

panels,

pinnacles,

and carving.

MONUMENTS:

GERMANY (C = cathedral; A = abbey; tr. =

transepts).--13th century:

Transitional

churches: Bamberg C.;

Naumburg C.; Collegiate

Church, Fritzlar; St.

George,

Limburg-on-Lahn;

St. Castor, Coblentz;

Heisterbach A.;--all in early

years of 13th

century.

St. Gereon, Cologne, choir

121227; Liebfrauenkirche, Treves, 122744;

St.

Elizabeth,

Marburg, 123583; Sts. Peter

and Paul, Neuweiler, 1250;

Cologne C., choir

12481322

(nave 14th century; towers

finished 1883); Strasburg

C., 125075 (E.

end

Romanesque;

fa�ade 12771365; tower 142939);

Halberstadt C., nave 1250

(choir

1327;

completed 1490); Altenburg

C., choir 125565 (finished

1379); Wimpfen-im-Thal

church

125978; St. Lawrence, Nuremberg,

1260 (choir 143977); St.

Catherine,

Oppenheim,

12621317 (choir 1439); Xanten,

Collegiate Church, 1263; Freiburg

C.,

1270

(W. tower 1300; choir 1354);

Toul C., 1272; Meissen C.,

choir 1274 (nave

131242);

Ratisbon C., 1275; St.

Mary's, L�beck, 1276; Dominican

churches at

Coblentz,

Gebweiler; and in Switzerland at

Basle, Berne, and

Zurich.--14th century:

Wiesenkirche,

S�st, 1313; Osnabr�ck C., 1318

(choir 1420); St. Mary's,

Prentzlau,

1325;

Augsburg C., 13211431; Metz C., 1330

rebuilt (choir 1486); St.

Stephen's C.,

Vienna,

1340 (nave 15th century; tower

1433); Zwette C., 1343;

Prague C., 1344;

church

at Thann, 1351 (tower finished 16th

century); Liebfrauenkirche,

Nuremberg,

135561;

St. Sebaldus Church,

Nuremberg, 136177 (nave Romanesque);

Minden C.,

choir

1361; Ulm C., 1377 (choir 1449; nave

vaulted 1471; finished 16th century);

Sta.

Barbara,

Kuttenberg, 1386 (nave

1483); Erfurt C.;

St. Elizabeth,

Kaschau;

Schlettstadt

C.--15th century: St. Catherine's,

Brandenburg, 1401; Frauenkirche,

Esslingen,

1406 (finished 1522); Minster at

Berne, 1421; Peter-Paulskirche,

G�rlitz,

142397;

St. Mary's, Stendal, 1447;

Frauenkirche, Munich, 146888; St.

Martin's,

Landshut,

1473.

SECULAR MONUMENTS. Schloss Marienburg, 1341;

Moldau-bridge and tower,

Prague,

1344;

Karlsteinburg, 134857; Albrechtsburg,

Meissen, 147183; Nassau

House,

Nuremberg,

1350; Council houses (Rathha�ser) at

Brunswick, 1393; Cologne,

140715;

Basle;

Breslau; L�beck; M�nster;

Prague; Ulm; City Gates of

Basle, Cologne,

Ingolstadt,

Lucerne.

THE NETHERLANDS.

Brussels C. (Ste. Gudule), 122680;

Tournai C., choir 1242

(nave

finished

1380); Notre Dame, Bruges,

123997; Notre Dame, Tongres, 1240;

Utrecht C.,

1251;

St. Martin, Ypres, 1254;

Notre Dame, Dinant, 1255;

church at Dordrecht;

church

at

Aerschot, 1337; Antwerp C., 13521411

(W. front 14221518); St.

Rombaut,

Malines,

135566 (nave 145664); St.

Wandru, Mons, 14501528; St.

Lawrence,

Rotterdam,

1472; other 15th century churches--St.

Bavon, Haarlem; St.

Catherine,

Utrecht;

St. Walpurgis, Sutphen; St.

Bavon, Ghent (tower 1461);

St. Jaques, Antwerp;

St.

Pierre,

Louvain; St. Jacques,

Bruges; churches at Arnheim,

Breda, Delft; St.

Jacques,

Li�ge,

1522.--SECULAR: Cloth-hall, Ypres, 12001304;

cloth-hall, Bruges, 1284; town

hall,

Bruges, 1377; town hall, Brussels,

140155; town hall, Louvain, 144863;

town

hall,

Ghent, 1481; town hall, Oudenarde, 1527;

Standehuis, Delft, 1528; cloth-halls

at

Louvain,

Ghent, Malines.

SPAIN.--13th

century: Burgos C., 1221

(fa�ade 144256; chapels 1487;

cimborio

1567);

Toledo C., 122790 (chapels 14th

and 15th centuries); Tarragona

C., 1235;

Leon

C., 1250 (fa�ade 14th century);

Valencia C., 1262 (N. transept

13501404;

fa�ade

13811418); Avila C., vault

and N. portal 12921353 (finished

14th century);

St.

Esteban, Burgos; church at

Las Huelgas.--14th century:

Barcelona C., choir

1298

1329

(nave and transepts 1448;

fa�ade 16th century); Gerona

C., 131246 (nave

added

1416);

S. M. del Mar, Barcelona, 132883; S. M.

del Pino, Barcelona, same

date;

Collegiate

Church, Manresa, 1328; Oviedo

C., 1388 (tower very late);

Pampluna C.,

1397

(mainly 15th century).--15th century:

Seville C., 1403 (finished 16th

century;

cimborio

151767); La Seo, Saragossa (finished

1505); S. Pablo, Burgos, 141535;

El

Parral,

Segovia, 1459; Astorga C., 1471;

San Juan de los Reyes,

Toledo, 1476;

Carthusian

church, Miraflores, 1488; San

Juan, and La Merced,

Burgos.--16th century:

Huesca

C., 1515; Salamanca New Cathedral,

151060; Segovia C., 1522; S. Juan de

la

Puerta,

Zamorra.

SECULAR.--Porta

Serra�os, Valencia, 1349; Casa

Consistorial, Barcelona, 136978;

Casa

de

la Disputacion, same city;

Casa de las Lonjas,

Valencia, 1482.

PORTUGAL.

At Batalha, church and

mausoleum of King Manoel,

finished 1515; at Belem,

monastery,

late Gothic.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.