|

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT |

| << GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER >> |

CHAPTER

XVI.

GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Adamy,

Corroyer, Enlart, Hasak,

Moore, Reber,

caract�res

de l'architecture fran�aise.

Davies, Architectural

Studies in France.

Ferree,

The

Chronology of the Cathedral

Churches of France.

Johnson, Early

French

Architecture.

King, The

Study book of Medi�val

Architecture and Art.

Lassus and

Viollet-le-Duc,

Notre

Dame de Paris.

Nesfield, Specimens

of Medi�val Architecture.

Pettit,

Architectural

Studies in France.

CATHEDRAL-BUILDING

IN FRANCE. In the

development of the principles

outlined

in the foregoing chapter the

church-builders of France led the way.

They

surpassed

all their contemporaries in readiness of

invention, in quickness and

directness

of reasoning, and in artistic refinement.

These qualities were

especially

manifested

in the extraordinary architectural

activity which marked the second

half

of

the twelfth century and the first half of the

thirteenth. This was the

great age of

cathedral-building

in France. The adhesion of the bishops to

the royal cause, and

their

position in popular estimation as the

champions of justice and human

rights,

led

to the rapid advance of the episcopacy in

power and influence. The cathedral,

as

the

throne-church of the bishop, became a

truly popular institution. New

cathedrals

were

founded on every side,

especially in the Royal Domain and the

adjoining

provinces

of Normandy, Burgundy, and Champagne, and their

construction was

warmly

seconded by the people, the communes, and

the municipalities. "Nothing to-

covered

Europe with railway lines,

can give an idea of the zeal

with which the urban

populations

set about building

cathedrals; . . . a necessity at the end

of the twelfth

century

because it was an energetic

protest against feudalism." The

collapse of the

unscientific

Romanesque vaulting of some of the

earlier cathedrals and the

destruction

by fire of others stimulated this

movement by the necessity for

their

immediate

rebuilding. The entire reconstruction of

the cathedrals of Bayeux,

Bayonne,

Cambray, Evreux, Laon,

Lisieux, Le Mans, Noyon, Poitiers,

Senlis,

Bourges,

Chartres, Paris, and Tours, and the abbey

of St. Denis, all of the

first

importance,

were begun during the same

period, and during the next

quarter-century

those

of Amiens, Auxerre, Rouen,

Reims, S�ez, and many others.

After 1250 the

movement

slackened and finally ceased. Few

important cathedrals were

erected

during

the latter half of the thirteenth century, the

chief among them being

at

Beauvais

(actively begun 1247), Clermont,

Coutances, Limoges, Narbonne,

and

Rodez.

During this period, and through the fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries,

French

architecture

was concerned rather with the

completion and remodelling of

existing

cathedrals

than the founding of new ones. There

were, however, many

important

parish

churches and civil or domestic

edifices erected within this

period.

STRUCTURAL

DEVELOPMENT: VAULTING. By the

middle of the twelfth century

the

use of barrel-vaulting over the

nave had been generally

abandoned and groined

vaulting

with its isolated points of

support and resistance had taken

its place. The

timid

experiments of the Clunisian architects

at V�zelay in the use of the

pointed

arch

and vault-ribs also led, in the

second half of the twelfth century, to

far-reaching

results.

The builders of the great Abbey

Church of

St.

Denis,

near Paris, begun in

1140

by the Abbot Suger, appear to

have been the first to

develop these

tentative

devices

into a system. In the original choir of

this noble church all the arches,

alike

of

the vault-ribs (except the groin-ribs,

which were semi-circles) and of the

openings,

were

pointed and the vaults were

throughout constructed with cross-ribs,

wall-ribs,

and

groin-ribs. Of this early work only the

chapels remain. In other

contemporary

monuments,

as for instance in the cathedral of Sens,

the adoption of these

devices

was

only partial and hesitating.

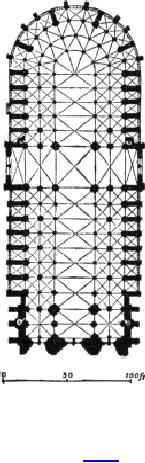

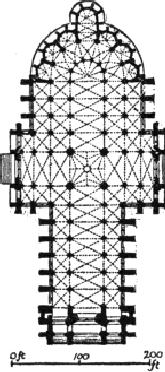

FIG.

116.--PLAN OF NOTRE DAME,

PARIS.

NOTRE

DAME AT PARIS. The next

great step in advance was

taken in the cathedral

Sully

in 1163, on the site of the twin cathedrals of

Ste. Marie and St. �tienne,

and

the

choir was, as usual, the

first portion erected. By 1196 the

choir, transepts, and

one

or two bays of the nave were

substantially finished. The completeness,

harmony,

and

vigor of conception of this remarkable

church contrast strikingly with

the

makeshifts

and hesitancy displayed in many

contemporary monuments in

other

provinces.

The difficult vaulting over the

radiating bays of the double

ambulatory

was

here treated with great

elegance. By doubling the number of

supports in the

exterior

circuit of each aisle (Fig.

116) each trapezoidal bay of the

vaulting was

divided

into three easily managed

triangular compartments. Circular

shafts were used

between

the central and side aisles. The

side aisles were doubled and

those next the

centre

were built in two stories, providing

ample galleries behind a very

open

triforium.

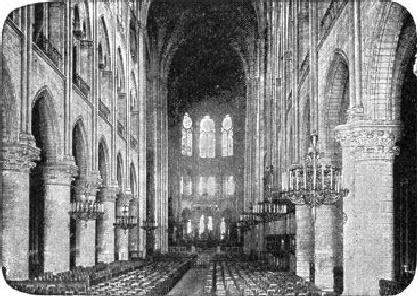

The nave was unusually lofty and covered

with six-part vaults of

admirable

execution.

The vault-ribs were vigorously

moulded and each made to

spring from a

distinct

vaulting-shaft, of which three rested

upon the cap of each of the

massive

piers

below (Fig. 117). The Cathedral

of

Bourges,

begun 1190, closely

resembled

that

of Paris in plan. Both were

designed to accommodate vast

throngs in their

exceptionally

broad central aisles and

double side aisles, but

Bourges has no side-

aisle

galleries, though the inner aisles are

much loftier than the outer ones.

Though

later

in date the vaulting of Bourges is

inferior to that of Notre Dame,

especially in

the

treatment of the trapezoidal bays of the

ambulatory.

FIG.

117.--INTERIOR OF NOTRE DAME,

PARIS.

The

masterly examples set by the

vault-builders of St. Denis and

Notre Dame were

not

at once generally followed. Noyon,

Senlis, and Soissons, contemporary

with

these,

are far less completely

Gothic in style. At Le

Mans the

groined vaulting which

in

1158 was substituted for the original

barrel-vault of the cathedral is of

very

primitive

design, singularly heavy and

awkward, although nearly

contemporary with

that

of Notre Dame (Fig.

118).

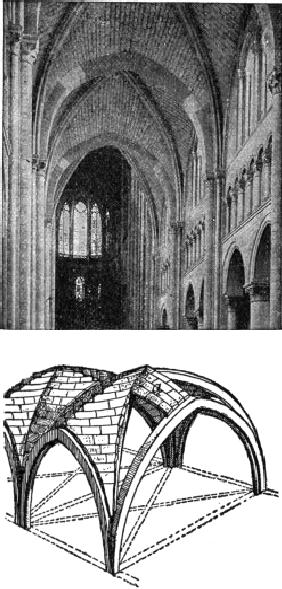

DOMICAL

GROINED VAULTING. The

builders of the South and West,

influenced

by

Aquitanian models, adhered to the

square plan and domical form of

vaulting-bay,

even

after they had begun to employ

groin-ribs. The latter, as at first

used by them in

imitation

of Northern examples, had no organic function in the

vault, which was still

built

like a dome. About 11451160 the

cathedral of St.

Maurice at

Angers

was

vaulted

with square, groin-ribbed vaults,

domical in form but not in

construction.

The

joints no longer described

horizontal circles as in a dome, but

oblique lines

perpendicular

to the groins and meeting in zigzag

lines at the ridge (Fig. 119).

This

method

became common in the West and

was afterward generally

adopted by the

English

architects. The Cathedrals

of

Poitiers

(1162) and

Laval

(La

Trinit�, 1180

1185)

are examples of this system, which at Le

Mans met with the Northern system

and

produced in the cathedral the awkward

compromise described

above.

FIG.

118.--LE MANS CATHEDRAL. NAVE.

FIG.

119.--GROINED VAULT WITH ZIG-ZAG

RIDGE-JOINTS.

a

shows

a small section of filling with

courses parallel to the

ridge, for comparison with

the

other compartments.

THIRTEENTH-CENTURY

VAULTING. Early

in the thirteenth century the

church-

builders

of Northern France abandoned the use of

square vaulting-bays and

six-part

vaults.

By the adoption of groin-ribs and the

pointed arch, the building of

vaults in

oblong

bays was greatly simplified.

Each bay of the nave could

now be covered with

its

own vaulting-bay, thus doing away with

all necessity for alternately light

and

heavy

piers. It is not quite certain when and

where this system was first

adopted for

the

complete vaulting of a church. It

is, however, probable that the

Cathedral

of

Chartres,

begun in 1194 and completed before 1240,

deserves this distinction,

although

it is possible that the vaults of

Soissons and Noyon may slightly antedate

it.

Troyes

(11701267),

Rouen

(12021220),

Reims

(12121242),

Auxerre

(1215

1234,

nave fourteenth century),

Amiens

(12201288),

and nearly all the great

churches

and chapels begun after 1200,

employ the fully developed oblong

vault.

BUTTRESSING.

Meanwhile

the increasing height of the clearstories

and the use of

double

aisles compelled the bestowal of

especial attention upon the buttressing.

The

nave

and choir of Chartres, the choirs of

Notre Dame, Bourges, Rouen,

and Reims,

the

chevet and later the choir of

St. Denis, afford early

examples of the flying-

arches

spanned the side aisles; in

Notre Dame they crossed the

double aisles in a

single

leap. Later the buttresses

were given greater stability

by the added weight of

lofty

pinnacles. An intermediate range of

buttresses and pinnacles was built

over the

intermediate

piers where double aisles

flanked the nave and choir, thus

dividing the

single

flying arch into two arches. At the same

time a careful observation of

statical

defects

in the earlier examples led to the

introduction of subordinate arches and

of

other

devices to stiffen and to beautify the

whole system. At Reims

and

Amiens

these

features received their highest

development, though later examples

are

frequently

much more ornate.

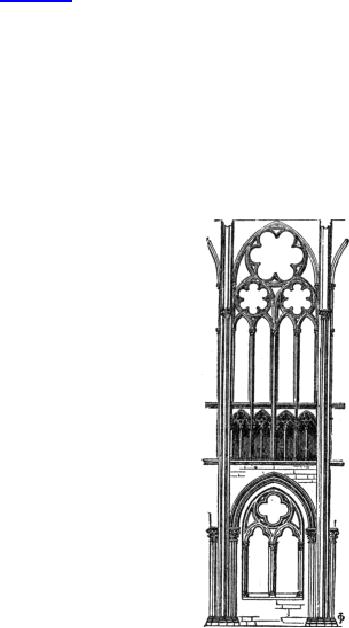

FIG.

120.--ONE BAY, ABBEY OF ST.

DENIS.

INTERIOR

DESIGN. The

progressive change outlined in the

last chapter, by which

the

wall was practically suppressed, the

windows correspondingly enlarged,

and

every

part of the structure made loftier and

more slender, resulted in the

evolution of

a

system of interior design well

represented by the nave of Amiens. The

second story

or

gallery over the side aisle

disappeared, but the aisle itself

was very high. The

triforium

was no longer a gallery, but a richly

arcaded passage in the thickness of

the

wall,

corresponding to the roofing-space over

the aisle, and generally treated

like a

lower

stage of the clearstory. Nearly the whole

space above it was occupied

in each

bay

by the vast clearstory window filled with

simple but effective geometric

tracery

over

slender mullions. The side

aisles were lighted by windows which,

like those in

the

clearstory, occupied nearly the whole

available wall-space under the vaulting.

The

piers

and shafts were all clustered and

remarkably slender. The whole

construction of

this

vast edifice, which covers

nearly eighty thousand

square feet, is a marvel

of

lightness,

of scientific combinations, and of fine

execution. Its great vault rises to

a

height

of one hundred and forty feet. The nave

of St. Denis, though less

lofty,

resembles

it closely in style (Fig. 120).

Earlier cathedrals show less of the

harmony of

proportion,

the perfect working out of the relation

of all parts of the composition of

each

bay, so conspicuous in the Amiens type,

which was followed in most of the

later

churches.

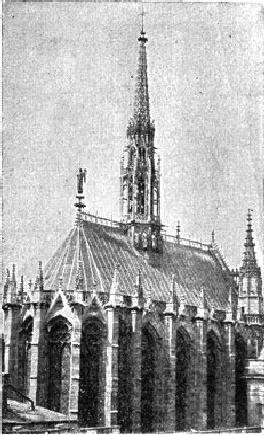

FIG.

121.--THE STE. CHAPELLE,

PARIS.

WINDOWS:

TRACERY. The

clearstory windows of Noyon, Soissons,

Sens, and the

choir

of V�zelay (1200) were simple

arched openings arranged

singly, in pairs, or in

threes.

In the cathedral of Chartres (11941220) they

consist of two arched

windows

with a circle above them, forming a

sort of plate tracery under a

single

arch.

In the chapel windows of the choir at

Reims (1215) the tracery of mullions

and

circles

was moulded inside and out, and the

intermediate triangular spaces

all

pierced

and glazed. Rose windows were

early used in front and transept

fa�ades.

During

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries

they were made of vast size

and great

lightness

of tracery, as in the transepts of Notre

Dame (1257) and the west front of

Amiens

(1288). From the design of these windows

is derived the name Rayonnant,

often

applied to the French Gothic

style of the period 12751375.

THE

SAINTE CHAPELLE. In this

beautiful royal chapel at

Paris, built 124247,

Gothic

design was admirably

exemplified in the noble windows 15 by 50

feet in size,

which

perhaps furnished the models for

those of Amiens and St.

Denis. Each was

divided

by slender mullions into four lancet-like

lights gathered under the rich

tracery

of the window-head. They were filled with

stained glass of the most

brilliant

but

harmonious hues. They occupy the

whole available wall-space, so that the

ribbed

vault

internally seems almost to

rest on walls of glass, so

slender are the

visible

supports

and so effaced by the glow of color in

the windows. Certainly lightness

of

construction

and the suppression of the wall-masonry

could hardly be carried further

than

here (Fig. 121). Among other

chapels of the same type are

those in the palace of

St.

Germain-en-Laye (1240), and a later

example in the ch�teau of Vincennes,

begun

by

Charles VI., but not finished till

1525.

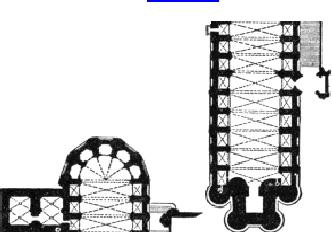

FIG.

122.--PLAN OF AMIENS

CATHEDRAL.

PLANS.

The

most radical change from the

primitive basilican type was, as

already

explained

in the last chapter, the continuation of

the side aisles around the

apse to

form

a chevet; and

later, the addition of chapels

between the external

buttresses.

Radiating

chapels, usually semi-octagons or

semi-decagons in plan, early appeared

as

additions

to the chevet

(Fig.

122). These may have originated in the

apsidal chapels

of

Romanesque churches in Auvergne and the

South, as at Issoire,

Clermont-Ferrand,

Le

Puy, and Toulouse. They generally

superseded the transept-chapels of

earlier

churches,

and added greatly to the beauty of the

interior perspective, especially

when

the

encircling aisles of the chevet

were doubled. Notre Dame, as

at first erected, had

a

double ambulatory, but no chapels.

Bourges has only five very

small semicircular

chapels.

Chartres (choir 1220) and Le Mans, as

reconstructed about the same

date,

have

double ambulatories and radial

chapels. After 1220 the second

ambulatory no

longer

appears. Noyon, Soissons, Reims,

Amiens, Troyes, and Beauvais,

Tours,

Bayeux,

and Coutances, Clermont, Limoges, and

Narbonne all have the

single

ambulatory

and radiating chevet-chapels. The

Lady-chapel in the axis of the

church

was

often made longer and more

important than the other chapels, as at

Amiens, Le

Mans,

Rouen, Bayeux, and Coutances.

Chapels also flanked the

choir in most of the

cathedrals

named above, and Notre Dame

and Tours also have side

chapels to the

nave.

The only cathedrals with complete double

side aisles alike to nave,

choir, and

chevet,

were Notre Dame and Bourges.

It is somewhat singular that the

German

cathedral

of Cologne is the only one in which all

these various characteristic

French

features

were united in one design

(see Fig.

140).

FIG.

123.--PLAN OF

CATHEDRAL

OF ALBY.

Local

considerations had full sway in France,

in spite of the tendency toward unity

of

type.

Thus Dol, Laon, and Poitiers have

square eastward terminations;

Ch�lons has

no

ambulatory; Bourges no transept. In

Notre Dame the transept was

almost

suppressed.

At Soissons one transept, at Noyon both,

had semicircular ends. Alby,

a

late cathedral of brick,

founded in 1280, but mostly built during the

fourteenth

century,

has neither side aisles nor

transepts, its wide nave

being flanked by

chapels

separated

by internal buttresses (Fig.

123).

SCALE.

The

French cathedrals were

nearly all of imposing dimensions. Noyon,

one

of

the smallest, is 333 feet long;

Sens measures 354. Laon,

Bourges, Troyes,

Notre

Dame,

Le Mans, Rouen, and Chartres vary from 396 to 437

feet in extreme

length;

Reims

measures 483, and Amiens, the longest of

all, 521 feet. Notre Dame is

124

feet

wide across the five aisles

of the nave; Bourges, somewhat wider. The

central

aisles

of these two cathedrals, and of Laon,

Amiens, and Beauvais, have a

span of not

far

from 40 feet from centre to centre of the

piers; while the ridge of the

vaulting,

which

in Notre Dame is 108 feet

above the pavement, and in Bourges 125,

reaches

in

Amiens a height of 140 feet, and of

nearly 160 in Beauvais. This

emphasis of the

height,

from 3 to 3� times the clear width of the

nave or choir, is one of the

most

striking

features of the French cathedrals. It

produces an impressive effect, but

tends

to

dwarf the great width of the central

aisle.

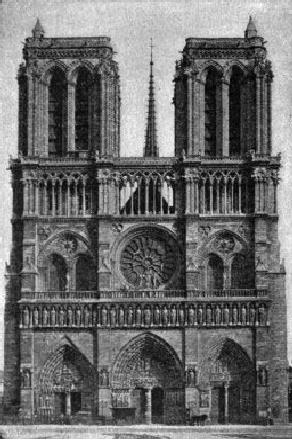

FIG.

124.--WEST FRONT OF NOTRE DAME,

PARIS.

EXTERIOR

DESIGN. Here,

as in the interior, every feature had

its constructive

raison

d'�tre, and the

total effect was determined

by the fundamental structural

scheme.

This was especially true of the

lateral elevations, in which the

pinnacled

buttresses,

the flying arches, and the traceried

windows of the side aisle

and

clearstory,

repeated uniformly at each bay, were the

principal elements of the

design.

The

transept fa�ades and main front allowed

greater scope for invention and

fancy,

but

even here the interior

membering gave the key to the

composition. Strong

buttresses

marked the division of the aisles and

resisted the thrust of the

terminal

pier

arches, and rose windows filled the

greater part of the wall space under the

end

of

the lofty vaulting. The whole structure

was crowned by a steep-pitched

roof of

wood,

covered with lead, copper, or

tiles, to protect the vault from damage

by snow

and

moisture. This roof

occasioned the steep gables which

crowned the transept and

main

fa�ades. The main front was frequently

adorned, above the triple

portal, with a

gallery

of niches or tabernacles filled with

statues of kings. Different

types of

composition

are represented by Chartres,

Notre Dame, Amiens, Reims,

and Rouen, of

which

Notre Dame (Fig. 124) and

Reims are perhaps the

finest. Notre Dame is

especially

remarkable for its stately

simplicity and the even balancing of

horizontal

and

vertical elements.

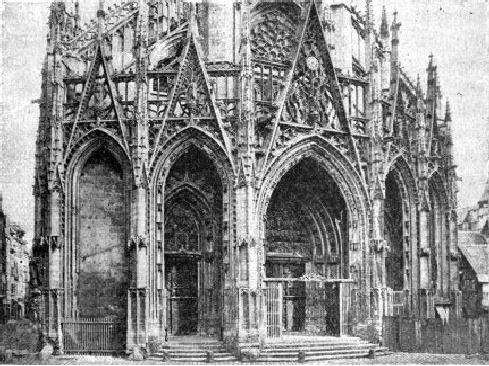

FIG.

125.--WEST FRONT OF ST.

MACLOU, ROUEN.

PORCHES.

In

most French church fa�ades the

porches were the most

striking

features,

with their deep shadows and sculptured

arches. The Romanesque

porches

were

usually limited in depth to the

thickness of the front wall. The Gothic

builders

secured

increased depth by projecting the

portals out beyond the wall, and

crowned

them

with elaborate gables. The vast

central door was divided in

two by a pier

adorned

with a niche and statue. Over this the tympanum of the

arch was carved

with

scriptural reliefs; the jambs and

arches were profusely

adorned with figures of

saints,

apostles, martyrs, and angels, under

elaborate canopies. The porches of

Laon,

Bourges,

Amiens, and Reims are

especially deep and majestic in

effect, the last-

named

(built 1380) being the richest of all.

Some of the transept fa�ades

also had

imposing

portals. Those of Chartres

(12101245)

rank among the finest works

of

Gothic

decorative architecture, the south

porch in some respects

surpassing that of

the

north transept. The portals of the

fifteenth and early sixteenth

centuries were

remarkable

for the extraordinary richness and

minuteness of their tracery and

sculpture,

as at Abbeville, Alen�on, the cathedral

and St. Maclou at Rouen

(Fig.

125),

Tours, Troyes, Vend�me,

etc.

TOWERS

AND SPIRES. The

emphasizing of vertical elements

reached its fullest

expression

in the towers and spires of the churches.

What had been at first merely

a

lofty

belfry roof was rapidly

developed into the spire, rising

three hundred feet or

more

into the air. This development had

already made progress in the

Romanesque

period,

and the south spire of Chartres is a

notable example of late

twelfth-century

steeple

design. The transition from the square

tower to the slender octagonal

pyramid

was

skilfully effected by means of corner

pinnacles and dormers. During and

after

the

thirteenth century the development

was almost wholly in the direction

of

richness

and complexity of detail, not of radical

constructive modification. The

northern

spire of Chartres (1515) and the spires

of Bordeaux, Coutances, Senlis,

and

the

Flamboyant church of St. Maclou at Rouen,

illustrate this development. In

Normandy

central spires were common,

rising over the crossing of

nave and

transepts.

In some cases the designers of

cathedrals contemplated a group of

towers;

this

is evident at Chartres, Coutances, and

Reims. This intention was,

however,

never

realized; it demanded resources

beyond even the enthusiasm of the

thirteenth

century.

Only in rare instances were the

spires of any of the towers completed,

and

the

majority of the French towers

have square terminations, with

low-pitched

wooden

roofs, generally invisible from

below. In general, French

towers are marked

by

their strong buttresses, solid

lower stories, twin windows in each

side of the

belfry

proper--these windows being usually of

great size--and a skilful

management

of

the transition to an octagonal plan for the

belfry or the spire.

CARVING

AND SCULPTURE. The

general superiority of French

Gothic work was

fully

maintained in its decorative

details. Especially fine is the

figure sculpture,

which

in the thirteenth and fourteenth

centuries attained true nobility of

expression,

combined

with great truthfulness and delicacy of

execution. Some of its

finest

productions

are found in the great doorway

jambs of the west portals of

the

cathedrals,

and in the ranks of throned and adoring

angels which adorned their

deep

arches.

These reach their highest

beauty in the portals of Reims (1380).

The

tabernacles

or

carved niches in which such

statues were set were

important elements

in

the decoration of the exteriors of

churches.

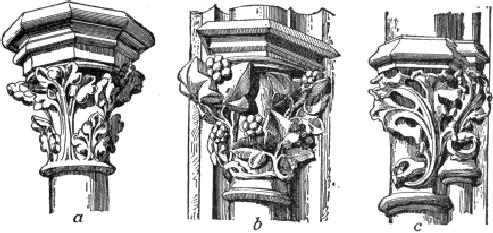

FIG.

126.--FRENCH GOTHIC

CAPITALS.

a,

From Sainte Chapelle, Paris,

13th century. b,

14th-century capital from

transept of

Notre

Dame, Paris. c,

15th-century capital from

north spire of

Chartres.

Foliage

forms were used for nearly

all the minor carved ornaments, though

grotesque

and

human figures sometimes took their

place. The gargoyles through which the

roof-

water

was discharged clear of the

building, were almost always

composed in the form

of

hideous monsters; and symbolic

beasts, like the oxen in the

towers of Laon, or

monsters

like those which peer from the

tower balustrades of Notre

Dame, were

employed

with some mystical significance in

various parts of the building. But

the

capitals

corbels, crockets, and finials

were mostly composed of

floral or foliage

forms.

Those of the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries were for the most part

simple in

mass,

and crisp and vigorous in design,

imitating the strong shoots of

early spring.

The

capitals

were

tall and slender, concave in profile,

with heavy square or

octagonal

abaci.

With the close of the thirteenth century

this simple and forcible style of

detail

disappeared.

The carving became more

realistic; the leaves, larger and

more mature,

were

treated as if applied to the capital or

moulding, not as if they grew out of

it.

The

execution and detail were

finer and more delicate, in harmony with

the

increasing

slenderness and lightness of the

architecture (Fig. 126 a,

b).

Tracery

forms

now

began to be profusely applied to all

manner of surfaces, and

open-work

gables,

wholly unnecessary from the structural point of view,

but highly effective as

decorations,

adorned the portals and crowned the

windows.

LATE

GOTHIC MONUMENTS. So far our

attention has been mainly

occupied with

the

masterpieces erected previous to 1250.

Among the cathedrals, relatively few

in

number,

whose construction is referable to the

second half of the century, that of

Beauvais

stands

first in importance. Designed on a

colossal scale, its

foundations

were

laid in 1225, but it was never

completed, and the portion built--the

choir and

chapels--belonged

really to the second half of the century,

having been completed

in

1270.

But the collapse in 1284 of the central

tower and vaulting of this

incomplete

cathedral,

owing to the excessive loftiness and

slenderness of its supports,

compelled

its

entire reconstruction, the number of the

piers being doubled and the

span of the

pier

arches correspondingly reduced. As thus

rebuilt, the cathedral aisle

was 47 feet

wide

from centre to centre of opposite

piers, and 163 feet high to the top of

the

vault.

Transepts were added after

1500. Limoges

and

Narbonne,

begun in 1272 on

a

large scale (though not

equal in size to Beauvais),

were likewise never

completed.

Both

had choirs of admirable plan, with

well-designed chevet-chapels. Many

other

cathedrals

begun during this period

were completed only after

long delays, as, for

instance,

Meaux, Rodez (1277), Toulouse (1272), and Alby (1282),

finished in the

sixteenth

century, and Clermont (1248), completed under

Napoleon III. But between

1260

or 1275 and 1350, work was actively

prosecuted on many still

incomplete

cathedrals.

The choirs of Beauvais (rebuilding),

Limoges, and Narbonne were

finished

after

1330; and towers, transept-fa�ades,

portals, and chapels added to many

others

of

earlier date.

The

style of this period is sometimes

designated as Rayonnant, from

the

characteristic

wheel tracery of the rose-windows, and

the prevalence of circular

forms

in

the lateral arched windows, of the

late thirteenth and early

fourteenth centuries.

The

great rose windows in the transepts of

Notre Dame, dating from 1257,

are

typical

examples of the style. Those of

Rouen cathedral belong to the

same category,

though

of later date. The fa�ade of

Amiens, completed by 1288, is one of the

finest

works

of this style, of which an early example

is the elaborate parish church of

St.

Urbain

at

Troyes.

THE

FLAMBOYANT STYLE. The

geometric treatment of the tracery and

the minute

and

profuse decoration of this period

gradually merged into the fantastic

and

unrestrained

extravagances of the Flamboyant

style,

which prevailed until the advent

of

the Renaissance--say 1525. The continuous

logical development of forms

ceased,

and

in its place caprice and

display controlled the arts of

design. The finest

monument

of this long period is the

fifteenth-century nave and central

tower of the

church

of St.

Ouen at

Rouen, a parish church of the first rank,

begun in 1318, but

not

finished until 1515. The tracery of the

lateral windows is still

chiefly geometric,

exhibit

in their tracery the florid decoration

and wavy, flame-like lines of this

style.

Slenderness

of supports and the suppression of

horizontal lines are here

carried to an

extreme;

and the church, in spite of its

great elegance of detail,

lacks the vital

interest

and charm of the earlier Gothic

churches. The cathedral of Alen�on and

the

church

of St.

Maclou at

Rouen, have portals with unusually

elaborate detail of

tracery

and carving; while the fa�ade of Rouen

cathedral (1509) surpasses all

other

examples

in the lace-like minuteness of its

open-work and its profusion of

ornament.

The

churches of St.

Jacques at

Dieppe, and of St.

Wulfrand at

Abbeville, the fa�ades

of

Tours and Troyes, are among the

masterpieces of the style. The upper part

of the

fa�ade

of Reims (13801428) belongs to the

transition from the Rayonnant to

the

Flamboyant.

While some works of this

period are conspicuous for the

richness of

their

ornamentation, others are

noticeably bare and poor in

design, like St. Merri

and

St.

S�verin in Paris.

SECULAR

AND MONASTIC ARCHITECTURE. The

building of cathedrals did not

absorb

all the architectural activity of the

French during the Gothic

period, nor did it

by

any means put an end to monastic

building. While there are

few Gothic cloisters

to

equal the Romanesque cloisters of

Puy-en-V�lay, Montmajour, Elne, and

Moissac,

many

of the abbeys either rebuilt their

churches in the Gothic style

after 1150, or

extended

and remodelled their conventual

buildings. The cloisters of

Fontfroide,

Chaise-Dieu,

and the Mont St. Michel rival those of

Romanesque times, while many

new

refectories and chapels were built in the

same style with the cathedrals.

The

most

complete of these Gothic

monastic establishments, that of the

Mont

St. Michel

in

Normandy, presented a remarkable

aggregation of buildings clustering

around the

steep

isolated rock on which stands the

abbey church. This was built in the

eleventh

century,

and the choir and chapels remodelled in

the sixteenth. The great

refectory

and

dormitory, the cloisters, lodgings, and

chapels, built in several vaulted

stories

against

the cliffs, are admirable

examples of the vigorous pointed-arch

design of the

early

thirteenth century.

Hospitals

like

that of St. Jean at Angers

(late twelfth century), or those of

Chartres,

Ourscamps,

Tonnerre, and Beaune, illustrate how

skilfully the French could modify

and

adapt the details of their architecture

to the special requirements of

civil

architecture.

Great numbers of charitable

institutions were built in the middle

ages--

asylums,

hospitals, refuges, and the like--but very few of

those in France are

now

extant.

Town halls were built in the fifteenth

century in some places where a

certain

amount

of popular independence had been

secured. The florid

fifteenth-century

Palais

de Justice at

Rouen

(14991508)

is an example of another branch of

secular

Gothic

architecture. In all these monuments the

adaptation of means to ends

is

admirable.

Wooden ceilings and roofs

replaced stone, wherever

required by great

width

of span or economy of construction.

There was little sculpture; the

wall-spaces

were

not suppressed in favor of stained

glass and tracery; while the roofs

were

usually

emphasized and adorned with elaborate

crestings and finials in lead or

terra-

cotta.

DOMESTIC

ARCHITECTURE. These

same principles controlled the

designing of

houses,

farm buildings, barns, granaries, and the

like. The common

closely-built

French

city house of the twelfth and thirteenth

century is illustrated by many

extant

examples

at Cluny, Provins, and other towns. A

shop opening on the street by a

large

arch,

a narrow stairway, and two or three

stories of rooms lighted by

clustered,

pointed-arched

windows, constituted the common

type. The street front was

usually

gabled

and the roof steep. In the fourteenth or

fifteenth century half-timbered

construction

began to supersede stone for town

houses, as it permitted of

encroaching

upon the street by projecting the upper

stories. Many of the half-

timbered

houses of the fifteenth century were of

elaborate design. The heavy

oaken

uprights

were carved with slender

colonnettes; the horizontal sills,

bracketed out

over

the street, were richly moulded;

picturesque dormers broke the

sky-line, and the

masonry

filling between the beams

was frequently faced with

enamelled tiles.

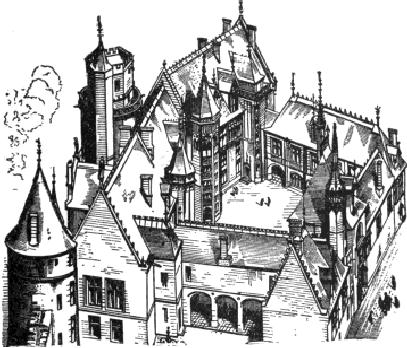

FIG.

127.--HOUSE OF JACQUES COEUR,

BOURGES.

(After

Viollet-le-Duc.)

The

more considerable houses or

palaces of royalty, nobles, and wealthy

citizens

rivalled,

and in time surpassed, the monastic

buildings in richness and splendor.

The

earlier

examples retain the military

aspect, with moat and donjon, as in the

Louvre of

Charles

V., demolished in the sixteenth century. The

finest palaces are of late

date,

and

the type is well represented by the Ducal

Palace at Nancy (1476), the Hotel

de

Cluny

(1485) at

Paris, the Hotel

Jacques Coeur at

Bourges (Fig. 127), and the

east

wing

of Blois (14981515). These palaces

are not only excellently and

liberally

planned,

with large halls, many staircases, and

handsome courts; they are

also

extremely

picturesque with their square and

circular towers, slender

turrets,

elaborate

dormers, and rich carved

detail.

MONUMENTS:

(C. = cathedral; A. = abbey;

trans. = transept; each

edifice is given

under

the date of its

commencement; subsequent alterations in

parentheses.) Between

1130

and 1200: V�zelay A.,

ante-chapel, 1130; St. Germer-de-Fly

C., 11301150

(chapel

later); St. Denis A.,

choir, 1140 (choir rebuilt,

nave and trans., 1240);

Sens C.,

114068

(W. front, 13th century;

chapels, spire, 14th);

Senlis C., 114583

(trans.,

spire,

13th century); Noyon C., 11491200

(W. front, vaults, 13th

century); St.

Germain-des-Pr�s

A., Paris, choir, 1150

(Romanesque nave); Angers

C., 1150 (choir,

trans.,

1274); Langres, 11501200; Laon

C., 11501200; Le Mans C.,

nave, 115058

(choir,

121754); Soissons C., 116070

(choir, 1212; nave chapels, 14th

century);

Poitiers

C., 11621204; Notre Dame,

Paris, choir, 116396 (nave, W.

front finished,

1235;

trans. fronts, and chapels,

125775); Chartres C., W. end, 1170;

rest, mainly

119498

(trans. porches, W. rose, 12101260;

N. spire, 1506); Tours C.,

1170

(rebuilt,

1267; trans., portals, 1375; W. portals,

chapels, 15th century; towers

finished,

150747);

Laval C., 118085 (choir, 16th

century); Mantes, church

Notre Dame,

11801200;

Bourges C., 119095 (E.

end, 1210; W. end, 1275);

St. Nicholas at Caen,

1190

(vaults, 15th century); Reims,

church St. R�my, choir,

end of 12th century

(Romanesque

nave); church St. Leu

d'Esserent, choir late 12th

century (nave, 13th

century);

Lyons C., choir, end of 12th

century (nave, 13th and 14th

centuries); Etampes,

church

Notre Dame, 12th and 13th

centuries.--13th century: Evreux

C., 120275

(trans.,

central tower, 1417; W. front

rebuilt, 16th century); Rouen

C., 120220 (trans.

portals,

1280; W. front, 1507); Nevers, 1211, N.

portal, 1280 (chapels, S. portal,

15th

century);

Reims C., 121242 (W.

front, 1380; W. towers, 1420);

Bayonne C., 1213

(nave,

vaults, W. portal, 14th century);

Troyes C., choir, 1214

(central tower, nave,

W.

portal, and towers, 15th

century); Auxerre C., 121534

(nave, W. end, trans.,

14th

century);

Amiens C., 122088; St.

Etienne at Chalons-sur-Marne, 1230

(spire, 1520);

S�ez

C., 1230, rebuilt 1260 (remodelled 14th

century); Notre Dame de

Dijon, 1230;

Reims,

Lady chapel of Archbishop's

palace, 1230; Chapel Royal at

St. Germain-en-Laye,

1240;

Ste. Chapelle at Paris, 124247

(W. rose, 15th century);

Coutances C., 125474;

Beauvais

C., 124772 (rebuilt 133747;

trans. portals, 150048); Notre

Dame de

Grace

at Clermont, 1248 (finished 1350); D�l

C., 13th century; St.

Martin-des-Champs

at

Paris, nave 13th century

(choir Romanesque); Bordeaux

C., 1260; Narbonne

C.,

12721320;

Limoges, 1273 (finished 16th century);

St. Urbain, Troyes,

1264;

Rodez

C., 12771385 (altered, completed

16th century); church St.

Quentin, 1280

1300;

St. Benigne at Dijon, 128091;

Alby C., 1282 (nave, 14th;

choir, 15th century;

S.

portal, 14731500); Meaux C.,

mainly rebuilt 1284 (W. end

much altered 15th,

finished

16th century); Cahors C.,

rebuilt 128593 (W. front, 15th

century); Orl�ans,

12871328

(burned, rebuilt 16011829).--14th

century: St. Bertrand de

Comminges,

130450;

St. Nazaire at Carcassonne,

choir and trans. on

Romanesque nave;

Montpellier

C., 1364; St. Ouen at Rouen,

choir, 131839 (trans., 140039;

nave,

146491;

W. front, 1515); Royal

Chapel at Vincennes, 1385 (?)-1525.--15th

and 16th

century:

St. Nizier at Lyons rebuilt;

St. S�verin, St. Merri,

St. Germain l'Auxerrois, all

at

Paris;

Notre Dame de l'Epine at

Chalons-sur-Marne; choir of St.

Etienne at Beauvais;

Saintes

C., rebuilt, 1450; St.

Maclou at Rouen (finished 16th

century); church at

Brou;

St.

Wulfrand at Abbeville; abbey of

St. Riquier--these three all

early 16th century.--

HOUSES,

CASTLES,

AND

PALACES:

Bishop's palace at Paris, 1160

(demolished); castle of

Coucy,

122030; Louvre at Paris (the

original ch�teau), 12251350; Palais

de Justice at

Paris,

originally the royal

residence, 12251400; Bishop's palace

at Laon, 1245

(addition

to Romanesque hall); castle

Montargis, 13th century; castle

Pierrefonds,

Bishop's

palace at Narbonnne, palace of

Popes at Avignon--all 14th century;

donjon of

palace

at Poitiers, 1395; H�tel des

Ambassadeurs at Dijon, 1420; house of

Jacques Coeur

at

Bourges, 1443; Palace, Dijon, 1467;

Ducal palace at Nancy, 1476;

H�tel Cluny at

Paris,

1490; castle of Creil, late 15th

century, finished in 16th; E. wing

palace of Blois,

14981515,

for Louis XII.; Palace de

Justice at Rouen, 14991508.

CATH�DRALE,

CHAPELLE,

CONSTRUCTION,

�GLISE,

MAISON,

VO�TE.

21.

Dictionnaire

raisonn� de l'architecture

fran�aise,

vol. ii., pp. 280, 281.

22.

See

Ferree, Chronology

of Cathedral Churches of

France.

23.

This

cathedral will be hereafter referred to,

for the sake of brevity, by

the name

of

Notre

Dame.

Other cathedrals having the

same name will be distinguished by

the

addition

of the name of the city, as

"Notre Dame at Clermont-Ferrand."

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.