|

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING |

| << EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT >> |

CHAPTER

XV.

GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Adamy, Architektonik

des gotischen Stils.

Corroyer,

L'Architecture

gothique.

Enlart, Manuel

d'arch�ologie fran�aise.

Hasak, Einzelheiten

des

Kirchenbaues

(in

Hdbuch

d. Arch.).

Moore, Development

and Character of

Gothic

Architecture.

Parker, Introduction

to Gothic Architecture. Scott,

Medi�val

Architecture.

Viollet-le-Duc,

Discourses

on Architecture;

Dictionnaire

raisonn� de l'architecture

fran�aise.

INTRODUCTORY.

The

architectural styles which were

developed in Western

Europe

during

the period extending from about 1150 to

1450 or 1500, received in an

unscientific

age the wholly erroneous and inept name

of Gothic. This name

has,

however,

become so fixed in common

usage that it is hardly possible to

substitute for

it

any more scientific designation. In

reality the architecture to which it is

applied

was

nothing more than the sequel and

outgrowth of the Romanesque, which we

have

already

studied. Its fundamental principles

were the same; it was

concerned with the

same

problems. These it took up

where the Romanesque builders left them,

and

worked

out their solution under new conditions, until it had

developed out of the

simple

and massive models of the early twelfth

century the splendid cathedrals of

the

thirteenth

and fourteenth centuries in England,

France, Germany, the Low Countries

and

Spain.

THE

CHURCH AND ARCHITECTURE. The twelfth

century was an era of

transition

in

society, as in architecture. The ideas of

Church and State were

becoming more

clearly

defined in the common mind. In the

conflict between feudalism and

royalty

the

monarchy was steadily

gaining ground. The problem of human

right was

beginning

to present itself alongside of the

problem of human might. The

relations

between

the crown, the feudal barons, the pope,

bishops, and abbots, differed

widely

in

France, Germany, England, and other

countries. The struggle among them

for

supremacy

presented itself, therefore, in

varied aspects; but the general

outcome was

essentially

the same. The church began to appear as

something behind and

above

abbots,

bishops, kings, and barons. The

supremacy of the papal authority

gained

increasing

recognition, and the episcopacy began to

overshadow the monastic

institutions;

the bishops appearing generally, but

especially in France, as the

champions

of popular rights. The prerogatives of

the crown became more firmly

established,

and thus the Church and the State emerged

from the social confusion as

the

two institutions divinely appointed for

the government of men.

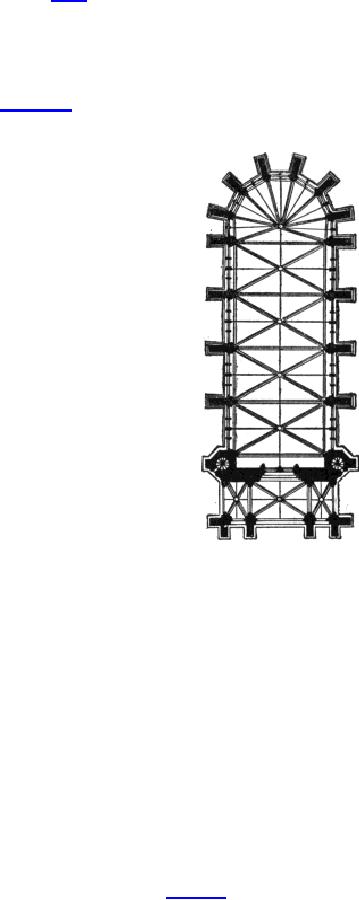

FIG.

105.--CONSTRUCTIVE SYSTEM OF GOTHIC

CHURCH,

ILLUSTRATING

PRINCIPLES OF ISOLATED SUPPORTS AND

BUTTRESSING.

Under

these influences ecclesiastical

architecture advanced with rapid

strides. No

longer

hampered by monastic restrictions, it

called into its service the laity,

whose

guilds

of masons and builders carried from

one diocese to another their

constantly

increasing

stores of constructive knowledge. By a

wise division of labor, each

man

wrought

only such parts as he was

specially trained to undertake. The

master-

builder--bishop,

abbot, or mason--seems to have

planned only the general

arrangement

and scheme of the building, leaving the

precise form of each detail to

be

determined

as the work advanced, according to the

skill and fancy of the artisan

to

whom

it was intrusted. Thus was

produced that remarkable variety in unity

of the

Gothic

cathedrals; thus, also, those

singular irregularities and makeshifts,

those

discrepancies

and alterations in the design, which are

found in every great work of

medi�val

architecture. Gothic architecture

was constantly changing,

attacking new

problems

or devising new solutions of old ones. In

this character of constant flux

and

development

it contrasts strongly with the classic

styles, in which the scheme and

the

principles were easily fixed

and remained substantially unchanged for

centuries.

STRUCTURAL

PRINCIPLES. The

pointed arch, so commonly

regarded as the most

characteristic

feature of the Gothic styles,

was merely an incidental

feature of their

development.

What really distinguished them most

strikingly was the

systematic

application

of two principles which the Roman and

Byzantine builders had

recognized

and applied, but which seem to have

been afterward forgotten until

they

were

revived by the later Romanesque

architects. The first of these

was the

concentration

of strains upon

isolated points of support,

made possible by the

substitution

of groined for barrel vaults.

This led to a corresponding

concentration of

the

masses of masonry at these

points; the building was

constructed as if upon legs

(Fig.

105). The wall became a mere filling-in

between the piers or buttresses, and

in

time

was, indeed, practically

suppressed, immense windows filled with

stained glass

taking

its place. This is well

illustrated in the Sainte

Chapelle at

Paris, built 1242

47

(Figs. 106, 122).

In this remarkable edifice, a series of

groined vaults spring

from

slender

shafts built against deep

buttresses which receive and resist all

the thrusts.

The

wall-spaces between them are wholly

occupied by superb windows filled

with

stone

tracery and stained glass. It would be

impossible to combine the materials

used

more

scientifically or effectively. The

cathedrals of Gerona (Spain) and of

Alby

(France;

Fig.

123)

illustrate the same principle, though in

them the buttresses are

internal

and serve to separate the flanking

chapels.

FIG.

106.--PLAN OF SAINTE CHAPELLE,

PARIS, SHOWING SUPPRESSION OF

SIDE-WALLS.

The

second distinctive principle of

Gothic architecture was that of

balanced

thrusts.

In

Roman buildings the thrust of the

vaulting was resisted wholly by the

inertia of

mass

in the abutments. In Gothic architecture

thrusts were as far as possible

resisted

by

counter-thrusts, and the final resultant

pressure was transmitted by flying

half-

arches

across the intervening portions of the

structure to external buttresses

placed

at

convenient points. This

combination of flying half-arches and

buttresses is called

the

flying-buttress

(Fig.

107). It reached its highest

development in the thirteenth and

fourteenth

centuries in the cathedrals of central

and northern France.

RIBBED

VAULTING. These

two principles formed the structural

basis of the Gothic

styles.

Their application led to the

introduction of two other elements,

second only to

them

in importance, ribbed

vaulting and the

pointed

arch.

The

first of these resulted from the

effort to overcome certain

practical difficulties

encountered

in the building of large groined

vaults. As ordinarily

constructed,

a

groined vault like that in Fig.

47,

must be built as one structure, upon

wooden

centrings

supporting its whole

extent.

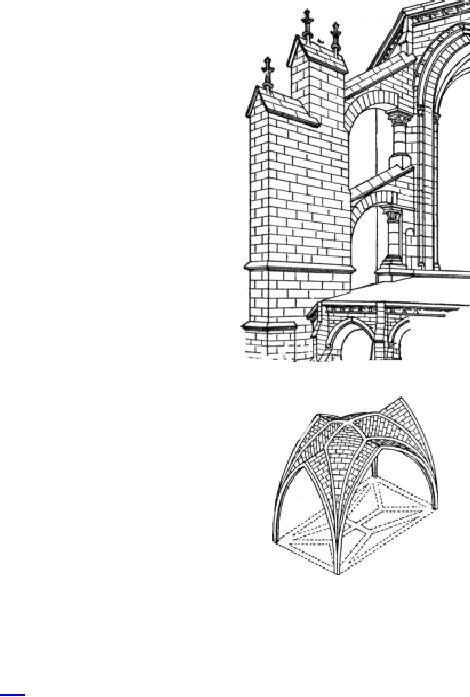

FIG.

107.--EARLY GOTHIC FLYING

BUTTRESS.

FIG.

108.--RIBBED VAULT, ENGLISH TYPE, WITH

DIVIDED GROIN-RIBS AND

RIDGE-RIBS.

The

Romanesque architects conceived the

idea of constructing an

independent

skeleton

of ribs. Two of these were built

against the wall (wall-ribs), two

across the

nave

(transverse ribs); and two others

were made to coincide with the

groins (Figs.

98,

108). The groin-ribs,

intersecting at the centre of the vault,

divided each bay into

four

triangular portions, or compartments,

each of which was really an

independent

vault

which could be separately constructed

upon light centrings supported by

the

groin-ribs

themselves. This principle, though

identical in essence with the

Roman

system

of brick skeleton-ribs for concrete

vaults, was, in application and

detail,

superior

to it, both from the scientific and artistic point of

view. The ribs, richly

moulded,

became, in the hands of the Gothic

architects, important

decorative

features.

In practice the builder gave to

each set of ribs

independently the curvature

he

desired. The vaulting-surfaces were then

easily twisted or warped so as to fit

the

various

ribs, which, being already in

place, served as guides for their

construction.

FIG.

109.--PENETRATIONS AND INTERSECTIONS OF

VAULTS.

a,

a, Penetrations by small semi-circular

vaults sprung from same

level. b, Intersection by

small

semi-circular vault sprung

from higher level; groins

form wavy lines. c,

Intersection

by

narrow pointed vault sprung

from same level; groins

are plane curves.

THE

POINTED ARCH was

adopted to remedy the difficulties

encountered in the

construction

of oblong vaults. It is obvious that

where a narrow semi-cylindrical

vault

intersects

a wide one, it produces

either what are called

penetrations, as at

a

(Fig.

109),

or intersections like that at b, both of

which are awkward in aspect and

hard

to

construct. If, however, one or both

vaults be given a pointed

section, the narrow

vault

may be made as high as the wide one. It

is then possible, with but little

warping

of the vaulting surfaces, to make them

intersect in groins c, which

are

vertical

plane curves instead of wavy

loops like a

and

b.

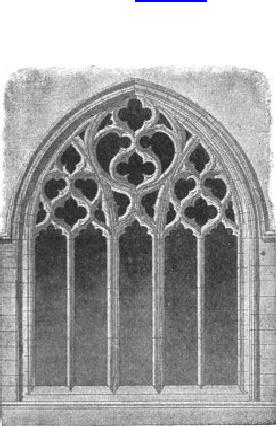

FIG.

110.--PLATE TRACERY,

CHARLTON-ON-OXMORE.

The

Gothic architects availed

themselves to the full of these two

devices. They built

their

groin-ribs of semi-circular or pointed

form, but the wall-ribs and the

transverse

ribs

were, without exception, pointed

arches of such curvature as would

bring the

apex

of each nearly or quite to the

level of the groin intersection. The

pointed arch,

thus

introduced as the most convenient form

for the vaulting-ribs, was soon

applied

to

other parts of the structure.

This was a necessity with the windows and

pier-

arches,

which would not otherwise fit well the wall-spaces

under the wall-ribs of the

nave

and aisle vaulting.

TRACERY

AND GLASS. With the

growth in the size of the windows and the

progressive

suppression of the lateral walls of

vaulted structures, stained

glass came

more

and more generally into use. Its

introduction not only resulted in a

notable

heightening

and enriching of the colors and scheme of

the interior decoration, but

reacted

on the architecture, intensifying the very

causes which led to its

introduction.

It

stimulated the increase in the size of

windows, and the suppression of the

walls,

and

contributed greatly to the development of

tracery.

This latter feature was

an

absolute

necessity for the support of the glass.

Its evolution can be traced

(Figs, 110,

111,

112) from the simple coupling of twin windows under a

single hood-mould, or

discharging

arch, to the florid net-work of the

fifteenth century. In its earlier

forms it

consisted

merely of decorative openings,

circles, and quatrefoils, pierced

through

slabs

of stone (plate-tracery),

filling the window-heads over

coupled windows.

Later

attention

was bestowed upon the form of the

stonework, which was made

lighter and

richly

moulded (bar-tracery),

rather than upon that of the openings

(Fig. 111). Then

the

circular and geometric patterns

employed were abandoned for

more flowing and

capricious

designs (Flamboyant

tracery,

Fig. 112) or (in England) for more

rigid and

rectangular

arrangements (Perpendicular, Fig.

134).

It will be shown later that the

periods

and styles of Gothic architecture

are more easily identified

by the tracery

than

by any other feature.

FIG.

111.--BAR TRACERY, ST. MICHAEL'S,

WARFIELD.

CHURCH

PLANS. The

original basilica-plan underwent

radical modifications

during

the

12th-15th centuries. These resulted in

part from the changes in

construction

which

have been described, and in part from

altered ecclesiastical conditions

and

requirements.

Gothic church architecture was

based on cathedral design; and

the

requirements

of the cathedral differed in many

respects from those of the

monastic

churches

of the preceding period.

The

most important alterations in the plan

were in the choir and transepts. The

choir

was

greatly lengthened, the transepts

often shortened. The choir

was provided with

two

and often four side-aisles, and one or

both of these was commonly

carried

entirely

around the apsidal termination of the

choir, forming a single or

double

ambulatory.

This combination of choir,

apse, and ambulatory was

called, in French

churches,

the chevet.

Another

advance upon Romanesque models

was the multiplication of

chapels--

a

natural consequence of the more popular

character of the cathedral as

compared

with

the abbey. Frequently lateral

chapels were built at each

bay of the side-aisles,

filling

up the space between the deep

buttresses, flanking the nave as well as

the

choir.

They were also carried

around the chevet

in

most of the French

cathedrals

(Paris,

Bourges, Reims, Amiens,

Beauvais, and many others); in many of

those in

Germany

(Magdeburg, Cologne, Frauenkirche at

Treves), Spain (Toledo,

Leon,

Barcelona,

Segovia, etc.), and Belgium (Tournay,

Antwerp). In England the choir

had

more

commonly a square eastward

termination. Secondary transepts

occur

frequently,

and these peculiarities, together with

the narrowness and great length

of

most

of the plans, make of the English

cathedrals a class by

themselves.

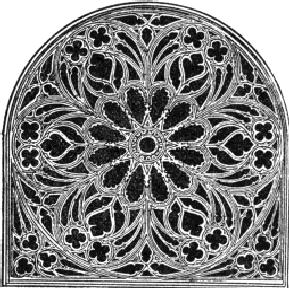

FIG.

112.--ROSE WINDOW, CHURCH OF

ST. OUEN, ROUEN.

PROPORTIONS

AND COMPOSITION. Along

with these modifications of the

basilican

plan should be noticed a great

increase in the height and slenderness of

all

parts

of the structure. The lofty clearstory, the

arcaded triforium-passage or

gallery

beneath

it, the high pointed pier-arches, the

multiplication of slender

clustered

shafts,

and the reduction in the area of the

piers, gave to the Gothic

churches an

interior

aspect wholly different from that of the

simpler, lower, and more

massive

Romanesque

edifices. The perspective effects of the

plans thus modified, especially

of

the

complex choir and chevet

with their

lateral and radial chapels,

were remarkably

enriched

and varied.

The

exterior was even more

radically transformed by these

changes, and by the

addition

of towers and spires to the fronts, and

sometimes to the transepts and to

their

intersection with the nave. The deep

buttresses, terminating in pinnacles,

the

rich

traceries of the great lateral

windows, the triple portals

profusely sculptured,

rose-windows

of great size under the front and

transept gables, combined to

produce

effects

of marvellously varied light and shadow,

and of complex and elaborate

structural

beauty, totally unlike the broad

simplicity of the Romanesque

exteriors.

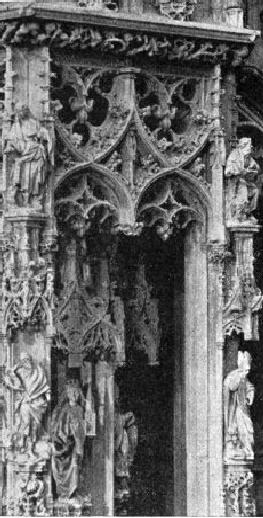

FIG.

113.--FLAMBOYANT DETAIL FROM PULPIT IN

STRASBURG CATHEDRAL.

DECORATIVE

DETAIL. The

medi�val designers aimed to

enrich every

constructive

feature

with the most effective play of lights

and shades, and to embody in the

decorative

detail the greatest possible amount of

allegory and symbolism, and

sometimes

of humor besides. The deep jambs and

soffits of doors and

pier-arches

were

moulded with a rich succession of hollow and

convex members, and

adorned

with

carvings of saints, apostles,

martyrs, and angels. Virtues and

vices, allegories of

reward

and punishment, and an extraordinary world of

monstrous and grotesque

beasts,

devils, and goblins filled the

capitals and door-arches, peeped

over tower-

parapets,

or leered and grinned from gargoyles and

corbels. Another source

of

decorative

detail was the application of

tracery like that of the windows to

wall-

panelling,

to balustrades, to open-work gables, to

spires, to choir-screens, and

other

features,

especially in the late fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries (cathedrals of

York,

Rouen,

Cologne; Henry VII.'s Chapel,

Westminster). And finally in the carving

of

capitals

and the ornamentation of mouldings the

artists of the thirteenth century

and

their

successors abandoned completely the

classic models and traditions which

still

survived

in the early twelfth century. The later

monastic builders began to

look

directly

to nature for suggestions of decorative

form. The lay builders who

sculptured

the

capitals and crockets and finials of the

early Gothic cathedrals

adopted and

followed

to its finality this principle of

recourse to nature, especially to plant

life. At

first

the budding shoots of early

spring were freely imitated

or skilfully

conventionalized,

as being by their thick and vigorous

forms the best adapted

for

translation

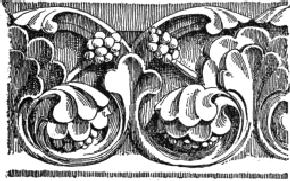

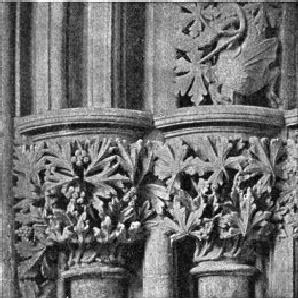

into stone (Fig. 114). During the

thirteenth century the more

advanced

stages

of plant growth, and leaves more complex

and detailed, furnished the

models

for

the carver, who displayed his

skill in a closer and more

literal imitation of their

minute

veinings and indentations (Fig.

115).

FIG.

114.--EARLY GOTHIC

CARVING.

This

artistic adaptation of natural

forms to architectural decoration

degenerated later

into

a minutely realistic copying of natural

foliage, in which cleverness of

execution

took

the place of original invention. The

spirit of display is characteristic of

all late

Gothic

work. Slenderness, minuteness of detail,

extreme complexity and intricacy

of

design,

an unrestrained profusion of decoration

covering every surface, a

lack of

largeness

and vigor in the conceptions, are

conspicuous traits of Gothic

design in the

fifteenth

century, alike in France, England,

Germany, Spain, and the Low

Countries.

Having

worked out to their conclusion the

structural principles bequeathed to

them

by

the preceding centuries, the authors of

these later works seemed to

have devoted

themselves

to the elaboration of mere decorative

detail, and in technical

finish

surpassed

all that had gone before (Fig.

113).

FIG.

115.--CARVING, DECORATED PERIOD,

FROM SOUTHWELL

MINSTER.

CHARACTERISTICS

SUMMARIZED. In the light

of the preceding explanations

Gothic

architecture may be defined as that

system of structural design

and

decoration

which grew up out of the effort to

combine, in one harmonious

and

organic

conception, the basilican plan with a

complete and systematic construction

of

groined

vaulting. Its development was

controlled throughout by considerations

of

stability

and structural propriety, but in the

application of these considerations

the

artistic

spirit was allowed full

scope for its exercise.

Refinement, good taste,

and

great

fertility of imagination characterize the

details and ornaments of

Gothic

structures.

While the Greeks in harmonizing the

requirements of utility and beauty

in

architecture

approached the problem from the �sthetic

side, the Gothic

architects

did

the same from the structural side.

Their admirably reasoned

structures express as

perfectly

the idea of vastness, mystery, and

complexity as do the Greek temples

that

of

simplicity and monumental

repose.

The

excellence of Gothic architecture lay not

so much in its individual details as

in

its

perfect adaptation to the purposes for

which it was developed--its triumphs

were

achieved

in the building of cathedrals and large

churches. In the domain of civil

and

domestic

architecture it produced nothing

comparable with its ecclesiastical

edifices,

because

it was the requirements of the cathedral

and not of the palace, town-hall,

or

dwelling,

that gave it its form and

character.

PERIODS.

The

history of Gothic architecture is

commonly divided into three

periods,

which

are most readily

distinguished by the character of the

window-tracery. These

periods

were not by any means synchronous in the

different countries; but the

order

of

sequence was everywhere the

same. They are here given,

with a summary of the

characteristics

of each.

EARLY POINTED PERIOD.

[Early

French;

Early

English or

Lancet

Period

in England;

Early

German,

etc.] Simple groined vaults;

general simplicity and vigor of

design and

detail;

conventionalized foliage of small

plants; plate tracery, and narrow

windows

coupled

under pointed arch with circular

foiled openings in the window-head.

(In

France,

1160 to 1275.)

MIDDLE POINTED PERIOD.

[Rayonnant

in

France; Decorated

or

Geometric

in

England.]

Vaults

more perfect; in England

multiple ribs and liernes;

greater slenderness and

loftiness

of proportions; decoration much richer,

less vigorous; more

naturalistic

carving

of mature foliage; walls

nearly suppressed, windows of great

size, bar tracery

with

slender moulded or columnar

mullions and geometric combinations

(circles and

cusps)

in window-heads, circular (rose)

windows. (In France, 1275 to

1375.)

FLORID GOTHIC PERIOD.

[Flamboyant

in

France; Perpendicular

in

England.] Vaults of

varied

and richly decorated design; fan-vaulting

and pendants in England,

vault-ribs

curved

into fanciful patterns in Germany and

Spain; profuse and minute

decoration

and

cleverness of technical execution

substituted for dignity of design; highly

realistic

carving

and sculpture, flowing or flamboyant

tracery in France; perpendicular

bars

with

horizontal transoms and four-centred

arches in England; "branch-tracery"

in

Germany.

(In France, 1375 to 1525.)

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.