|

EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN |

| << EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING >> |

CHAPTER

XIV.

EARLY

MEDI�VAL ARCHITECTURE.--Continued.

IN

GERMANY, GREAT BRITAIN, AND

SPAIN.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before,

H�bsch and Reber. Bond,

Gothic

Architecture in

England.

Also Brandon, Analysis

of Gothic Architecture.

Boisser�e, Nieder

Rhein.

Ditchfield,

The

Cathedrals of England.

Hasak, Die

romanische und die

gotische

Baukunst

(in

Handbuch

d. Arch.).

L�bke, Die

Mittelalterliche Kunst in

Westfalen.

M�ller,

Denkm�ler

der deutschen Baukunst.

Puttrich, Baukunst

des Mittelalters in

Sachsen.

Rickman, An

Attempt to Discriminate the

Styles of Architecture.

Scott, English

Church

Architecture. Van

Rensselaer, English

Cathedrals.

MEDI�VAL

GERMANY. Architecture

developed less rapidly and

symmetrically in

Germany

than in France, notwithstanding the

strong centralized government of

the

empire.

The early churches were of

wood, and the substitution of stone for

wood

proceeded

slowly. During the Carolingian epoch (800919),

however, a few

important

buildings were erected,

embodying Byzantine and classic

traditions.

Among

these the most notable was

the Minster

or

palatine chapel of Charlemagne

at

Aix-la-Chapelle, an

obvious imitation of San

Vitale at Ravenna. It consisted of

an

octagonal

domed hall surrounded by a vaulted

aisle in two stories, but without

the

eight

niches of the Ravenna plan. It

was preceded by a porch

flanked by turrets. The

Byzantine

type thus introduced was

repeated in later churches, as in the

Nuns' Choir

at

Essen (947) and at Ottmarsheim (1050). In the

great monastery at Fulda

a

basilica

with transepts and with an apsidal choir

at either end was built in

803.

These

choirs were raised above the

level of the nave, to admit of

crypts beneath

them,

as in many Lombard churches; a practice

which, with the reduplication of the

choir

and apse just mentioned, became very

common in German

Romanesque

architecture.

EARLY

CHURCHES. It

was in Saxony that this architecture

first entered upon a

truly

national development. The early

churches of this province and of

Hildesheim

(where

architecture flourished under the favor

of the bishops, as elsewhere under

the

royal

influence) were of basilican plan and

destitute of vaulting, except in the

crypts.

They

were built with massive piers,

sometimes rectangular, sometimes

clustered, the

two

kinds often alternating in the

same nave. Short columns

were, however,

sometimes

used instead of piers,

either alone, as at Paulinzelle and

Limburg-on-the-

Hardt

(102439), or alternating with piers, as at

Hecklingen, Gernrode

(958

1050),

and St.

Godehard at

Hildesheim (1133). A triple eastern

apse, with apsidal

chapels

projecting eastward from the transepts,

were common elements in the

plans,

and

a second apse, choir, and crypt at the

west end were not

infrequent. Externally

the

most striking feature was

the association of two, four, or even six

square or

circular

towers with the mass of the church, and

the elevation of square or

polygonal

turrets

or cupolas over the crossing.

These adjuncts gave a very

picturesque aspect to

edifices

otherwise somewhat wanting in

artistic interest.

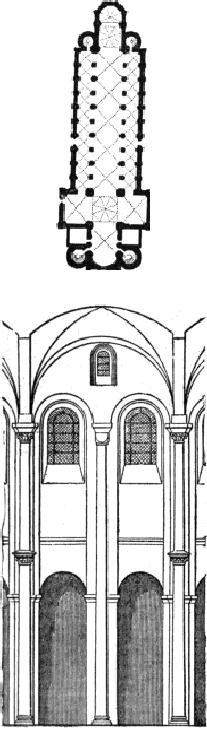

FIG.

99.--PLAN OF MINSTER AT

WORMS.

FIG.

100.--ONE BAY OF CATHEDRAL AT

SPIRES.

RHENISH

CHURCHES. It

was in the Rhine provinces that

vaulting was first

applied

to

the naves of German churches,

nearly a half century after its

general adoption in

France.

Cologne possesses an interesting trio of

churches in which the Byzantine

dome

on squinches or on pendentives, with

three apses or niches

opening into the

central

area, was associated with a

long three aisled nave

(St.

Mary-in-the-Capitol,

begun

in 9th century; Great

St. Martin's, 115070;

Apostles'

Church,

116099:

the

naves vaulted later). The

double chapel at Schwarz-Rheindorf,

near Bonn

(1151),

also has the crossing

covered by a dome on

pendentives.

The

vaulting of the nave itself

was developed in another

series of edifices of

imposing

size,

the cathedrals of Mayence

(1036),

Spires

(Speyer),

and Worms, and the

Abbey

of

Laach, all built in

the 11th century and vaulted early in the 12th. In the

first

three

the main vaulting is in square bays,

each covering two bays of the

nave, the

piers

of which are alternately lighter and

heavier (Figs. 99, 100). At Laach

the

vaulting-bays

are oblong, both in nave and

aisles. There was no triforium

gallery, and

stability

was secured only by excessive

thickness in the piers and clearstory

walls,

and

by bringing down the main vault as near to the

side-aisle roofs as

possible.

FIG.

101.--EAST END OF CHURCH OF

THE APOSTLES,

COLOGNE.

RHENISH

EXTERIORS. These

great churches, together with

those of Bonn

and

Limburg-on-the-Lahn

and the

cathedral of Treves

(Trier,

1047), are interesting, not

only

by their size and dignity of plan and the

somewhat rude massiveness of

their

construction,

but even more so by the picturesqueness

of their external design

(Fig.

101).

Especially successful is the massing of

the large and small turrets with the

lofty

nave-roof

and with the apses at one or both ends.

The systematic use of arcading

to

decorate

the exterior walls, and the introduction

of open arcaded dwarf

galleries

under

the cornices of the apses, gables, and

dome-turrets, gave to these

Rhenish

churches

an external beauty hardly equalled in

other contemporary edifices.

This

method

of exterior design, and the system of

vaulting in square bays over

double

bays

of the nave, were probably

derived from the Lombard churches of

Northern

Italy,

with which the Hohenstauffen emperors had many

political relations.

The

Italian influence is also

encountered in a number of circular

churches of early

date,

as at Fulda (9th-11th century), Dr�gelte,

Bonn (baptistery, demolished), and

in

fa�ades

like that at Rosheim, which is a copy in

little of San Zeno at

Verona.

Elsewhere

in Germany architecture was in a

backward state, especially in

the

southern

provinces. Outside of Saxony,

Franconia, and the Rhine provinces, very

few

works

of importance were erected until the

thirteenth century.

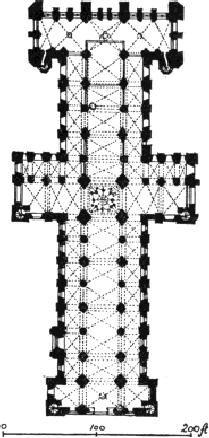

FIG.

102.--PLAN OF DURHAM CATHEDRAL.

SECULAR

ARCHITECTURE. Little

remains to us of the secular architecture

of this

period

in Germany, if we except the great feudal

castles, especially those of

the

Rhine,

which were, after all, rather

works of military engineering than

of

architectural

art. The palace of Charlemagne at Aix is known to

have been a vast and

splendid

group of buildings, partly, at least of

marble; but hardly a vestige of it

remains.

Of the extensive Palace

of Henry III. at

Goslar

there

remain well-defined

ruins

of an imposing hall of assembly in two

aisles with triple-arched windows.

At

Brunswick

the east wing of the Burg

Dankwargerode displays,

in spite of modern

alterations,

the arrangement of the chapel, great

hall, two fortified towers, and

part

of

the residence of Henry the Lion. The

Wartburg

palace

(Ludwig III., cir.

1150)

is

more

generally known--a rectangular hall in

three stories, with windows

effectively

grouped

to form arcades; while at Gelnhausen and

M�nzenberg are ruins of

somewhat

similar buildings. A few of the

Romanesque monasteries of Germany

have

left

partial remains, as at Maulbronn, which

was almost entirely rebuilt

in the Gothic

period,

and isolated buildings in Cologne and

elsewhere. There remain also

in

Cologne

a number of Romanesque private houses

with coupled windows and stepped

gables.

GREAT

BRITAIN. Previous

to the Norman conquest (1066) there was

in the British

Isles

little or no architecture worthy of mention. The few

extant remains of

Saxon

and

Celtic buildings reveal a

singular poverty of ideas and want of

technical skill.

These

scanty remains are mostly of

towers (those in Ireland

nearly all round and

tapering,

with conical tops, their use and

date being the subjects of

much

controversy)

and crypts. The tower of Earl's

Barton is the most important and

best

preserved

of those in England. With the Norman

conquest, however, began

an

extraordinary

activity in the building of churches and

abbeys. William the

Conqueror

himself

founded a number of these, and his Norman

ecclesiastics endeavored to

surpass

on British soil the contemporary

churches of Normandy. The new

churches

differed

somewhat from their French prototypes;

they were narrower and lower, but

much

longer, especially as to the choir and

transepts. The cathedrals of Durham

(10961133)

and Norwich

(same

date) are important examples

(Fig. 102). They also

differed

from the French churches in two important

particulars externally; a

huge

tower

rose usually over the

crossing, and the western portals

were small and

insignificant.

Lateral entrances near the

west end were given

greater importance and

called

Galilees. At Durham a

Galilee chapel (not shown in the plan),

takes the place

of

a porch at the west end,

like the ante-churches of St.

Beno�t-sur-Loire and V�zelay.

THE

NORMAN STYLE. The

Anglo-Norman builders employed the

same general

features

as the Romanesque builders of Normandy, but with

more of picturesqueness

and

less of refinement and technical

elegance. Heavy walls,

recessed arches, round

mouldings,

cubic cushion-caps, clustered

piers, and in doorways a jamb-shaft

for

each

stepping of the arch were

common to both styles. But in England the

Corinthian

form

of capital is rare, its

place being taken by simpler

forms.

NORMAN

INTERIORS. The

interior design of the larger

churches of this period

shows

a close general analogy to

contemporaneous French Norman churches,

as

appears

by comparing the nave of Waltham or

Peterboro' with that of

C�risy-la-For�t,

in

Normandy. Although the massiveness of the

Anglo-Norman piers and walls

plainly

suggests

the intention of vaulting the nave, this

intention seems never to

have been

carried

out except in small churches and

crypts. All the existing abbeys

and

cathedrals

of this period had wooden ceilings or

were, like Durham, Norwich, and

Gloucester,

vaulted at a later date.

Completed as they were with wooden

nave-roofs,

the

clearstory was, without danger,

made quite lofty and furnished with

windows of

considerable

size. These were placed

near the outside of the thick wall, and a

passage

was

left between them and a triple arch on

the inner face of the wall--a

device

imitated

from the abbeys at Caen. The vaulted

side-aisles were low, with

disproportionately

wide pier-arches, above which

was a high triforium gallery under

the

side-roofs. Thus a nearly equal

height was assigned to each

of the three stories of

the

bay, disregarding that subordination of minor to

major parts which gives

interest

to

an architectural composition. The piers

were quite often round, as at

Gloucester,

Hereford,

and Bristol. Sometimes round piers

alternated with clustered piers, as

at

Durham

and Waltham; and in some cases

clustered piers alone were

employed, as at

Peterboro'

and in the transepts of Winchester (Fig.

103).

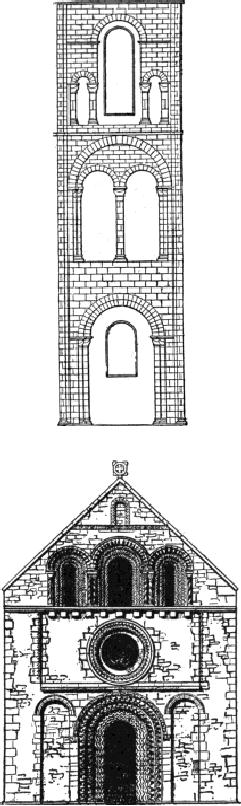

FIG.

103.--ONE BAY OF TRANSEPT, WINCHESTER

CATHEDRAL.

FIG.

104.--FRONT OF IFFLEY

CHURCH.

FA�ADES

AND DOORWAYS. All the

details were of the simplest

character, except

in

the doorways. These were richly

adorned with clustered jamb-shafts

and

elaborately

carved mouldings, but there

was little variety in the details of

this

carving.

The zigzag was the most

common feature, though birds'

heads with the

beaks

pointing toward the centre of the arch

were not uncommon. In the

smaller

churches

(Fig. 104) the doorways were

better proportioned to the whole fa�ade

than

in

the larger ones, in which they appear as

relatively insignificant features. Very

few

examples

remain of important Norman fa�ades in

their original form, nearly all

of

these

having been altered after

the round arch was displaced by the

pointed arch in

the

latter part of the twelfth century. Iffley church

(Fig. 104) is a good example

of

the

style.

SPAIN.

During the

Romanesque period a large

part of Spain was under

Moorish

dominion.

The capture of Toledo, in 1062, by the

Christians, began the

gradual

emancipation

of the country from Moslem rule, and in the northern

provinces a

number

of important churches were

erected under the influence of

French

Romanesque

models. The use of domical

pendentives (as in the Panteon

of

S.

Isidoro, at

Leon, and in the cimborio

or

dome over the choir at the

intersection of

nave

and transepts in old Salamanca cathedral)

was probably derived from

the

domical

churches of Aquitania and Anjou.

Elsewhere the northern Romanesque

type

prevailed

under various modifications, with long

nave and transepts, a short

choir,

and

a complete chevet

with

apsidal chapels. The church of St.

Iago at

Compostella

(1078)

is the finest example of this class.

These churches nearly all had

groined

vaulting

over the side-aisles and barrel-vaults

over the nave, the constructive

system

being

substantially that of the churches of

Auvergne and the Loire Valley.

They

differed,

however, in the treatment of the crossing

of nave and transepts, over

which

was

usually erected a dome or

cupola or pendentives or squinches,

covered externally

by

an imposing square lantern or tower, as

in the Old

Cathedral at

Salamanca,

already

mentioned (112078) and the Collegiate

Church at

Toro.

Occasional

exceptions

to these types are met with, as in the

basilican wooden-roofed church of

S.

Millan at Segovia; in S.

Isidoro at

Leon, with chapels and a later-added

square

eastern

end, and the circular church of the

Templars at Segovia.

The

architectural details of these

Spanish churches did not differ

radically from

contemporary

French work. As in France and England,

the doorways were the

most

ornate

parts of the design, the mouldings

being carved with extreme

richness and the

jambs

frequently adorned with statues, as in

S.

Vincente at

Avila. There was no

such

logical

and reasoned-out system of external

design as in France, and there

is

consequently

greater variety in the fa�ades.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing

about

the

architecture of this period is its

apparent exemption from the influence of

the

Moorish

monuments which abounded on every hand.

This may be explained by the

hatred

which was felt by the Christians for the

Moslems and all their works.

MONUMENTS.

GERMANY:

Previous to 11th century: Circular

churches of Holy Cross at

M�nster,

and of Fulda; palace chapel

of Charlemagne at Aix-la-Chapelle, 804;

St.

Stephen,

Mayence, 990; primitive nave

and crypt of St. Gereon,

Cologne, 10th century;

Lorsch.--11th

century: Churches of Gernrode,

Goslar, and Merseburg in

Saxony;

cathedral

of Bremen; first restoration of

cathedral of Treves (Trier), 1010,

west front,

1047;

Limburg-on-Hardt, 1024; St. Willibrod,

Echternach, 1031; east end of

Mayence

Cathedral,

1036; Church of Apostles and

nave St. Mary-in-Capitol at

Cologne, 1036;

cathedral

of Spires (Speyer) begun 1040;

Cathedral Hildesheim, 1061; St.

Joseph,

Bamberg,

1073; Abbey of Laach, 10931156;

round churches of Bonn,

Dr�gelte,

Nimeguen;

cathedrals of Paderborn and

Minden.--12th century: Churches of

Klus,

Paulinzelle,

Hamersleben, 11001110; Johannisberg, 1130;

St. Godehard.

Hildesheim,

1133;

Worms, the Minster, 111883;

Jerichau, 114460; Schwarz-Rheindorf, 1151;

St.

Michael,

Hildesheim, 1162; Cathedral Brunswick,

117294; Lubeck, 1172; also

churches

of Gaudersheim, W�rzburg, St.

Matthew at Treves, Limburg-on-Lahn,

Sinzig, St.

Castor

at Coblentz, Diesdorf, Rosheim;

round churches of Ottmarsheim

and Rippen

(Denmark);

cathedral of Basle, cathedral

and cloister of Zurich

(Switzerland).

ENGLAND:

Previous to 11th century: Scanty

vestiges of Saxon church

architecture, as

tower

of Earl's Barton, round

towers and small chapels in

Ireland.--11th century:

Crypt

of

Canterbury Cathedral, 1070; chapel

St. John in Tower of London,

1070; Winchester

Cathedral,

107693 (nave and choir

rebuilt later); Gloucester

Cathedral nave, 1089

1100

(vaulted later); Rochester

Cathedral nave, west front

cloisters, and

chapter-house,

10901130;

Carlisle Cathedral nave,

transepts, 10931130; Durham

Cathedral, 1095

1133,

vaulted 1233; Galilee and

chapter-house, 113353; Norwich

Cathedral, 1096,

largely

rebuilt 111893; Hereford Cathedral,

nave and choir,

10991115.--12th

century:

Ely Cathedral, nave, 110733;

St. Alban's Abbey, 1116;

Peterboro' Cathedral,

111745;

Waltham Abbey, early 12th

century; Church of Holy Sepulchre,

Cambridge,

113035;

Worcester Cathedral chapter-house, 1140

(?); Oxford Cathedral

(Christ

Church),

115080; Bristol Cathedral

chapter-house (square), 1155;

Canterbury

Cathedral,

choir of present structure by

William of Sens, 1175; Chichester

Cathedral,

11801204;

Romsey Abbey, late 12th

century; St. Cross Hospital

near Winchester,

1190

(?). Many more or less

important parish churches in

various parts of

England.

SPAIN.

For principal monuments of

9th-12th centuries, see

text, latter part of

this

chapter.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.