|

EARLY MEDIÃVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE |

| << SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE |

| EARLY MEDIÃVAL ARCHITECTURE.âContinued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN >> |

CHAPTER

XIII.

EARLY

MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE

IN

ITALY AND FRANCE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Cattaneo,

L'Architecture

en Italie.

Chapuy, Le

moyen age

monumental.

Corroyer, Architecture

romane.

Cummings, A

History of Architecture in

Italy.

Enlart, Manuel

d'archéologie française.

Hübsch, Monuments

de l'architecture

chrétienne.

Knight, Churches

of Northern Italy.

Lenoir, Architecture

monastique.

Osten,

Bauwerke

in der Lombardei.

Quicherat, Mélanges

d'histoire et d'archéologie.

Reber,

History

of Mediæval Architecture.

Révoil, Architecture

romane du midi de la

France.

Rohault de Fleury, Monuments

de Pise.

Sharpe, Churches

of Charente.

De

Verneilh,

L'Architecture

byzantine en France.

Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire

raisonné de

l'architecture

française (especially

in Vol. I., Architecture religieuse);

Discourses

on

Architecture.

EARLY

MEDIÆVAL EUROPE. The fall of

the Western Empire in 476 A.D.

marked

the

beginning of a new era in architecture

outside of the Byzantine Empire. The

so-

called

Dark Ages which followed this event

constituted the formative period of

the

new

Western civilization, during which the

Celtic and Germanic races

were being

Christianized

and subjected to the authority and to the educative

influences of the

Church.

Under these conditions a new architecture

was developed, founded upon

the

traditions

of the early Christian builders,

modified in different regions by

Roman or

Byzantine

influences. For Rome

recovered early her antique

prestige, and Roman

monuments

covering the soil of Southern

Europe, were a constant

object lesson to

the

builders of that time. To this new

architecture of the West, which in the

tenth

and

eleventh centuries first

began to achieve worthy and monumental

results, the

generic

name of Romanesque

has

been commonly given, in

spite of the great

diversity

of its manifestations in different

countries.

CHARACTER

OF THE ARCHITECTURE. Romanesque

architecture was pre-

eminently

ecclesiastical. Civilization and culture

emanated from the Church, and her

requirements

and discipline gave form to the builder's

art. But the basilican style,

which

had so well served her purposes in the

earlier centuries and on classic

soil,

was

ill-suited to the new conditions.

Corinthian columns, marble

incrustations, and

splendid

mosaics were not to be had for the asking

in the forests of Gaul or

Germany,

nor could the Lombards and Ostrogoths in

Italy or their descendants

reproduce

them. The basilican style was

complete in itself, possessing no

seeds of

further

growth. The priests and monks of Italy and

Western Europe sought to

rear

with

unskilled labor churches of

stone in which the general dispositions

of the

basilica

should reappear in simpler,

more massive dress, and, as far as

possible, in a

fireproof

construction with vaults of stone.

This problem underlies all the

varied

phases

of Romanesque architecture; its final

solution was not, however,

reached until

the

Gothic period, to which the Romanesque

forms the transition and

stepping-stone.

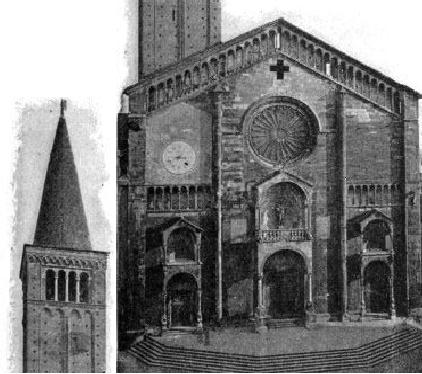

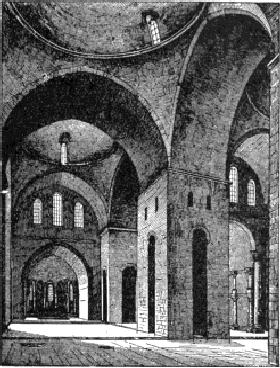

FIG.

90.--INTERIOR OF SAN AMBROGIO,

MILAN.

MEDIÆVAL

ITALY. Italy in the

Dark Ages stood midway between the

civilization of

the

Eastern Empire and the semi-barbarism of

the West. Rome, Ravenna, and

Venice

early

became centres of culture and

maintained continuous commercial

relations with

the

East. Architecture did not lack

either the inspiration or the means for

advancing

on

new lines. But its advance

was by no means the same

everywhere. The unifying

influence

of the church was counterbalanced by the

provincialism and the local

diversities

of the various Italian states, resulting

in a wide variety of styles.

These,

however,

may be broadly grouped in four divisions:

the Lombard, the

Tuscan-

Romanesque, the

Italo-Byzantine, and the

unchanged Basilican

or

Early Christian,

which

last, as was shown in Chapter X.,

continued to be practised in

Rome

throughout

the Middle Ages.

LOMBARD

STYLE. Owing to the

general rebuilding of ancient

churches under the

more

settled social conditions of the

eleventh and twelfth centuries, little

remains to

us

of the architecture of the three

preceding centuries in Italy, except the

Roman

basilicas

and a few baptisteries and circular

churches, already mentioned

in

Chapter

X. The so-called Lombard monuments

belong mainly to the eleventh and

twelfth

centuries. They are found not only in

Lombardy, but also in Venetia and

the

Æmilia.

Milan, Pavia, Piacenza, Bologna, and

Verona were important

centres of

development

of this style. The churches were

nearly all vaulted, but the plans

were

basilican,

with such variations as resulted from

efforts to meet the exigencies

of

vaulted

construction. The nave was

narrowed, and instead of rows of

columns

carrying

a thin clearstory wall, a few massive

piers of masonry, connected by

broad

pier-arches,

supported the heavy ribs of the

groined vaulting, as in S.

Ambrogio,

Milan

(Fig. 90). To resist the thrust of the main vault, the

clearstory was

sometimes

suppressed,

the side aisle carried up in two

stories forming galleries, and

rows of

chapels

added at the sides, their

partitions forming buttresses. The

piers were often

of

clustered section, the better to

receive the various arches and

ribs they supported.

The

vaulting was in square

divisions or vaulting-bays,

each embracing two

pier-

arches

which met upon an intermediate pier

lighter than the others. Thus the

whole

aspect

of the interior was revolutionized. The

lightness, spaciousness, and

decorative

elegance

of the basilicas were here

exchanged for a sombre and massive

dignity

severe

in its plainness. The Choir

was sometimes raised a few

feet above the nave,

to

allow

of a crypt and confessio

beneath,

reached by broad flights of

steps from the

nave.

Sta. Maria della Pieve at

Arezzo (9th-11th century), S.

Michele at

Pavia (late

11th

century), the Cathedral

of Piacenza (1122),

S.

Ambrogio at Milan

(12th

century),

and S.

Zeno at

Verona (1139) are notable

monuments of this style.

FIG.

91.--WEST FRONT AND

CAMPANILE

OF

CATHEDRAL, PIACENZA.

LOMBARD

EXTERIORS. The few

architectural embellishments employed on

the

simple

exteriors of the Lombard churches

were usually effective and well

composed.

Slender

columnettes or long pilasters, blind

arcades, and open arcaded

galleries

under

the eaves gave light and shade to

these exteriors. The façades

were mere

frontispieces

with a single broad gable, the

three aisles of the church being

merely

suggested

by flat or round pilasters dividing the front

(Fig 91). Gabled porches,

with

columns

resting on the backs of lions or

monsters, adorned the doorways.

The

carving

was often of a fierce and

grotesque character. Detached

bell-towers or

campaniles

adjoined

many of these churches; square and

simple in mass, but with

well-distributed

openings and well-proportioned belfries

(Piacenza S. Zeno at

Verona,

etc.).18

THE

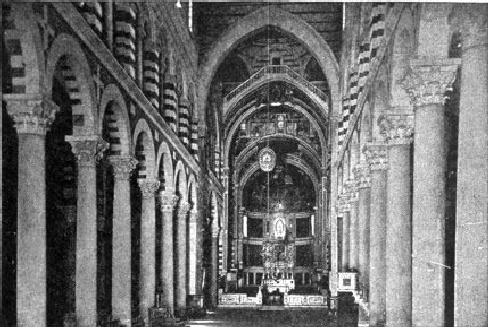

TUSCAN ROMANESQUE. The

churches of this style (sometimes

called the

Pisan)

were less vigorous but more

elegant and artistic in design than the

Lombard.

They

were basilicas in plan, with timber

ceilings and high clearstories on

columnar

arcades.

In their decoration, both internal and

external, they betray the influence

of

Byzantine

traditions, especially in the use of

white and colored marble in

alternating

bands

or in panelled veneering. Still

more striking is the external

decorative

application

of wall-arcades, sometimes occupying the

whole height of the wall and

carried

on flat pilasters, sometimes in

superposed stages of small

arches on slender

columns

standing free of the wall. In general the

decorative element prevailed

over

the

constructive in the design of these

picturesquely beautiful churches,

some of

which

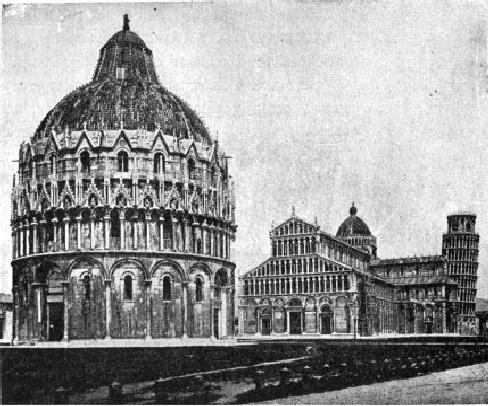

are of noble size. The

Duomo

(cathedral)

of Pisa, built

10631118, is the

finest

monument of the style (Figs. 92, 93). It is 312

feet long and 118 wide,

with

long

transepts and an elliptical dome of

later date over the

crossing

(the

intersection

of

nave and transepts). Its richly arcaded

front and banded flanks

strikingly

exemplify

the illogical and unconstructive but highly

decorative methods of the

Tuscan

Romanesque builders. The circular

Baptistery

(1153), with

its lofty domical

central

hall surrounded by an aisle, an imposing

development of the type

established

by

Constantine, and the famous Leaning

Tower (1174), both

designed with external

arcading,

combine with the Duomo to form the most

remarkable group of

ecclesiastical

buildings in Italy, if not in Europe

(Fig. 92).

FIG.

92.--BAPTISTERY, CATHEDRAL, AND LEANING

TOWER, PISA.

The

same style appears in more

flamboyant shape in some of the

churches of Lucca.

The

cathedral S.

Martino (1060;

façade, 1204; nave altered in

fourteenth century)

is

the finest and largest of these;

S.

Michele (façade,

1288) and S. Frediano (twelfth

century)

have the most elaborately

decorated façades. The same

principles of design

appear

in the cathedral and several other

churches in Pistoia and Prato; but

these

belong,

for the most part, to the Gothic

period.

FIG.

93.--INTERIOR OF PISA

CATHEDRAL.

FLORENCE.

The church of

S.

Miniato, in the

suburbs of Florence, is a

beautiful

example

of a modification of the Pisan style. It

is in plan a basilica with two

piers

interrupting

the colonnade on each side of the

nave and supporting

powerful

transverse

arches. The interior is embellished with

bands and patterns in black

and

white,

and the woodwork of the open-timber roof

is elegantly decorated with

fine

patterns

in red, green, blue, and

gold--a treatment common in

early mediæval

churches,

as at Messina, Orvieto, etc. The

exterior is adorned with wall-arches

of

classic

design and with panelled veneering in

white and dark marble, instead of

the

horizontal

bands of the Pisan churches.

This system of external

decoration,

a

blending of Pisan and Italo-Byzantine

methods, became the established

practice in

Florence,

lasting through the whole Gothic period.

The Baptistery

of

Florence,

originally

the cathedral, an imposing polygonal

domical edifice of the tenth

century,

presents

externally one of the most

admirable examples of this practice. Its

marble

veneering

in black and white, with pilasters and

arches of excellent design,

is

attributed

by Vasari to Arnolfo di Cambio, but is by

many considered to be much

older,

although restored by that architect in

1294.

Suggestions

of the Pisan arcade system

are found in widely scattered examples in

the

east

and south of Italy, mingled with features

of Lombard and Byzantine design.

In

Apulia,

as at Bari, Caserta Vecchia (1100),

Molfetta (1192), and in Sicily, the

Byzantine

influence is conspicuous in the use of

domes and in many of the

decorative

details.

Particularly is this the case at Palermo

and Monreale, where the

churches

erected

after the Norman conquest--some of them

domical, some basilican--show

a

strange

but picturesque and beautiful mixture of

Romanesque, Byzantine, and

Arabic

forms.

The Cathedral

of

Monreale

and the

churches of the Eremiti

and

La

Martorana

at

Palermo are the most

important.

The

Italo-Byzantine

style

has already found mention in the

latter part of Chapter XI.

Venice

and Ravenna were its chief

centres; while the influence, both of the

parent

style

and of its Italian offshoot was, as we

have just shown, very widespread.

WESTERN

ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE. In

Western Europe the unrest

and

lawlessness

which attended the unsettled relations of

society under the feudal

system

long

retarded the establishment of that social

order without which architectural

progress

is impossible. With the eleventh century

there began, however, a

great

activity

in building, principally among the

monasteries, which represented all

that

there

was of culture and stability

amid the prevailing disorder.

Undisturbed by war,

the

only abodes of peaceful labor,

learning, and piety, they had become rich

and

powerful,

both in men and land. Probably the more or

less general apprehension

of

the

supposed impending end of the world in

the year 1000 contributed to this

result

by

driving unquiet consciences to seek

refuge in the monasteries, or to endow

them

richly.

The

monastic builders, with little technical

training, but with plenty of willing

hands,

sought

out new architectural paths to meet their

special needs. Remote from

classic

and

Byzantine models, and mainly dependent on

their own resources, they

often

failed

to realize the intended results. But

skill came with experience, and

with

advancing

civilization and a surer mastery of

construction came a finer

taste and

greater

elegance of design. Meanwhile military

architecture developed a new

science

of

building, and covered Europe with

imposing castles, admirably

constructed and

often

artistic in design as far as military

exigencies would permit.

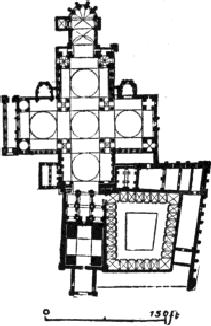

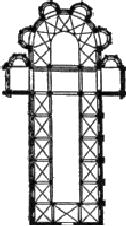

FIG.

94.--PLAN OF ST.

FRONT.

CHARACTER

OF THE STYLE. The

Romanesque architecture of the eleventh

and

twelfth

centuries in Western Europe

(sometimes called the Round-Arched

Gothic)

was

thus predominantly though not exclusively

monastic. This gave it a

certain unity

of

character in spite of national and

local variations. The problem which the

wealthy

orders

set themselves was, like

that of the Lombard church-builders in Italy, to

adapt

the

basilica plan to the exigencies of

vaulted construction. Massive

walls, round

arches

stepped or recessed to lighten

their appearance, heavy

mouldings richly

carved,

clustered piers and jamb-shafts,

capitals either of the cushion

type

or

imitated

from the Corinthian, and strong and

effective carving--all these

are features

alike

of French, German, English, and

Spanish Romanesque

architecture.

THE

FRENCH ROMANESQUE. Though

monasticism produced remarkable

results in

France,

architecture there did not wholly depend

upon the monasteries. Southern

Gaul

(Provence) was full of classic

remains and classic traditions while at

the same

Front

at

Perigueux, built in 1120, reproduced the plan of

St. Mark's with singular

fidelity,

but without its rich decoration, and with

pointed instead of round

arches

(Figs.

94, 95). The domical cathedral of

Cahors

(10501100),

an obvious imitation

of

S. Irene at Constantinople, and the later

and more Gothic Cathedral of

Angoulême

display

a notable advance in architectural

skill outside of the monasteries.

Among the

abbeys,

Fontevrault

(11011119)

closely resembles Angoulême, but

surpasses it in

the

elegance of its choir and

chapels. In these and a number of other

domical

churches

of the same Franco-Byzantine type in

Aquitania, the substitution of the

Latin

cross in the plan for the Greek cross

used in St. Front, evinces

the Gallic

tendency

to work out to their logical end new

ideas or new applications of old

ones.

These

striking variations on Byzantine

themes might have developed into

an

independent

local style but for the overwhelming

tide of Gothic influence which

later

poured

in from the North.

FIG.

95.--INTERIOR OF ST. FRONT,

PERIGUEUX.

Meanwhile,

farther south (at Arles,

Avignon, etc.), classic

models strongly

influenced

the

details, if not the plans, of an

interesting series of churches

remarkable especially

for

their porches rich with figure sculpture

and for their elaborately carved

details.

The

classic archivolt, the Corinthian

capital, the Roman forms of

enriched mouldings,

are

evident at a glance in the porches of

Notre Dame des Doms at

Avignon, of the

church

of St. Gilles, and of St.

Trophime at Arles.

FIG.

96.--PLAN OF NOTRE DAME DU PORT,

CLERMONT.

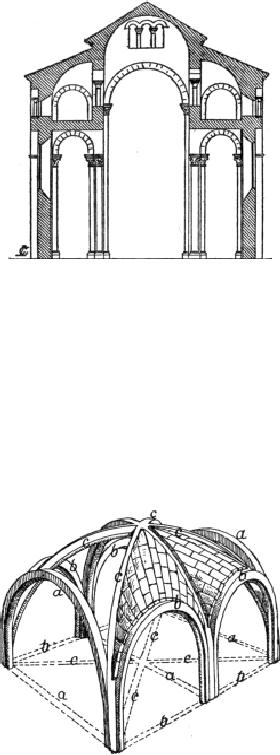

DEVELOPMENT

OF VAULTING. It

was in Central France, and mainly

along the

Loire,

that the systematic development of

vaulted church architecture began.

Naves

covered

with barrel-vaults appear in a number of

large churches built during

the

eleventh

and twelfth centuries, with apsidal and

transeptal chapels and aisles

carried

around

the apse, as in St. Etienne,

Nevers, Notre

Dame du Port at

Clermont-Ferrand

(Fig.

96), and St.

Paul at

Issoire. The thrust of these ponderous

vaults was clumsily

resisted

by half-barrel vaults over the

side-aisles, transmitting the strain to

massive

side-walls

(Fig. 97), or by high side-aisles with

transverse barrel or groined

vaults

over

each bay. In either case the

clearstory was suppressed--a

fact which mattered

little

in the sunny southern provinces. In the

more cloudy North, in Normandy,

Picardy,

and the Royal Domain, the nave-vault

was raised higher to admit

of

clearstory

windows, and its section was

in some cases made like a

pointed arch, to

diminish

its thrust, as at Autun. But

these eleventh-century vaults

nearly all fell in,

and

had to be reconstructed on new principles. In this

work the Clunisians seem to

have

led the way, as at Cluny

(1089) and

Vézelay

(1100). In the

latter church, one

of

the finest and most interesting

French edifices of the twelfth century, a

groined

vault

replaced the barrel-vault, though the

oblong plan of the vaulting-bays, due

to

the

nave being wider than the

pier-arches, led to somewhat awkward

twisted

surfaces

in the vaulting. But even here the

vaults had insufficient lateral

buttressing,

and

began to crack and settle; so that in the

great ante-chapel, built thirty

years

later,

the side-aisles were made in two

stories, the better to resist the thrust,

and the

groined

vaults themselves were

constructed of pointed section.

These seem to be the

earliest

pointed groined vaults in

France. It was not till the second half

of that

century,

however (11501200), that the flying buttress

was combined with

such

vaults,

so as to permit of high clearstories for the

better lighting of the nave; and

the

problem

of satisfactorily vaulting an oblong

space with a groined vault was

not

solved

until the following century.

FIG.

97.--SECTION OF NOTRE DAME DU PORT,

CLERMONT.

ONE-AISLED

CHURCHES. In the

Franco-Byzantine churches already

described this

difficulty

of the oblong vaulting-bay did not occur,

owing to the absence of

side-aisles

and

pier-arches. Following this conception of

church-planning, a number of

interesting

parish churches and a few cathedrals

were built in various parts of

France

in

which side-recesses or chapels took the

place of side-aisles. The

partitions

separating

them served as abutments for the groined

or barrel-vaults of the nave. The

cathedrals

of Autun

(1150) and

Langres

(1160), and in

the fourteenth century that

of

Alby, employed this arrangement, common

in many earlier Provençal

churches

which

have disappeared.

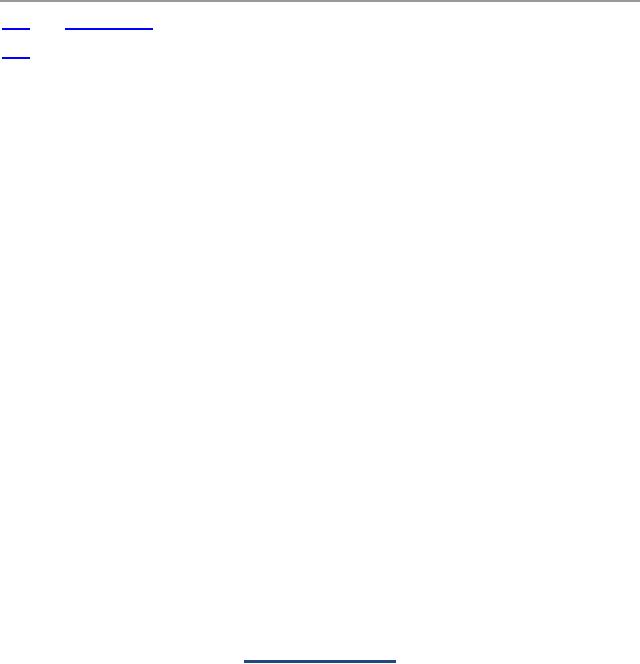

FIG.

98.--A SIX-PART RIBBED VAULT, SHOWING TWO

COMPARTMENTS WITH THE FILLINGS

COMPLETE.

a,

a, Transverse ribs (doubleaux); b, b,

Wall-ribs (formerets); c, c, Groin-ribs

(diagonaux).

(All

the ribs are

semicircles.)

SIX-PART

VAULTING. In the

Royal Domain great

architectural activity does

not

appear

to have begun until the beginning of the

Gothic period in the middle of

the

twelfth

century. But in Normandy, and especially at Caen and

Mont St. Michel, there

were

produced, between 1046 and 1120, some

remarkable churches, in which a

high

clearstory was secured in

conjunction with a vaulted nave, by the

use of "six-

part"

vaulting (Fig. 98). This was

an awkward expedient, by which a square

vaulting-

bay

was divided into six parts

by the groins and by a middle transverse

rib,

necessitating

two narrow skew vaults meeting at the

centre. This

unsatisfactory

device

was retained for over a century, and

was common in early Gothic

churches

both

in France and Great Britain. It

made it possible to resist the thrust by

high side-

aisles,

and yet to open windows above

these under the cross-vaults. The

abbey

churches

of St.

Etienne (the

Abbaye aux Hommes) and Ste.

Trinité (Abbaye

aux

Dames),

at Caen, built in the time of William the

Conqueror, were among the

most

magnificent

churches of their time, both in size and

in the excellence and ingenuity of

their

construction. The great abbey church of

Mont

St. Michel (much

altered in later

times)

should also be mentioned

here. At the same time these

and other Norman

churches

showed a great advance in their

internal composition. A

well-developed

triforium

or subordinate gallery was

introduced between the pier-arches

and

clearstory,

and all the structural membering of the

edifice was better

proportioned

and

more logically expressed than in

most contemporary work.

ARCHITECTURAL

DETAILS. The

details of French Romanesque

architecture varied

considerably

in the several provinces, according as

classic, Byzantine, or

local

influences

prevailed. Except in a few of the

Aquitanian churches, the round arch

was

universal.

The walls were heavy and built of

rubble between facings of

stones of

moderate

size dressed with the axe.

Windows and doors were widely

splayed to

diminish

the obstruction of the massive walls, and

were treated with jamb-shafts

and

recessed

arches. These were usually

formed with large cylindrical

mouldings, richly

carved

with leaf ornaments, zigzags,

billets, and grotesques. Figure-sculpture

was

more

generally used in the South than in the

North. The interior piers

were

sometimes

cylindrical, but more often

clustered, and where square

bays of four-part

or

six-part vaulting were

employed, the piers were

alternately lighter and

heavier.

Each

shaft had its independent

capital either of the block type or of a

form

resembling

somewhat that of the Corinthian order.

During the eleventh century it

became

customary to carry up to the main

vaulting one or more shafts

of the

compound

pier to support the vaulting

ribs. Thus the division of the nave into

bays

was

accentuated, while at the same time the

horizontal three-fold division of

the

height

by a well-defined triforium between the

pier-arches and clearstory began to

be

likewise

emphasized.

VAULTING.

The

vaulting was also divided

into bays by transverse ribs, and

where it

was

groined the groins themselves

began in the twelfth century to be marked

by

groin-ribs.

These were constructed

independently of the vaulting, and the four or

six

compartments

of each vaulting-bay were then built in,

the ribs serving, in part at

least,

to support the centrings for this

purpose. This far-reaching principle,

already

applied

by the Romans in their concrete

vaults, appears as a re-discovery, or

rather

an

independent invention, of the builders of

Normandy at the close of the

eleventh

century.

The flying buttress was a later

invention; in the round-arched buildings

of

the

eleventh and twelfth centuries the

buttressing was mainly internal, and

was

incomplete

and timid in its arrangement.

EXTERIORS.

The

exteriors were on this account

plain and flat. The windows were

small,

the mouldings simple, and towers

were rarely combined with the

body of the

church

until after the beginning of the twelfth century. Then

they appeared as mere

belfries

of moderate height, with pyramidal

roofs and effectively arranged

openings,

the

germs of the noble Gothic

spires of later times.

Externally the western

porches

and

portals were the most

important features of the design,

producing an imposing

effect

by their massive arches, clustered

piers, richly carved mouldings, and

deep

shadows.

CLOISTERS,

ETC. Mention

should be made of the other

monastic buildings which

were

grouped around the abbey

churches of this period. These

comprised refectories,

chapter-halls,

cloistered courts surrounded by the

conventual cells, and a

large

number

of accessory structures for kitchens,

infirmaries, stores, etc. The

whole

formed

an elaborate and complex aggregation of

connected buildings, often of

great

size

and beauty, especially the refectories

and cloisters. Most of these

conventual

buildings

have disappeared, many of them having

been demolished during the

Gothic

period

to make way for more elegant

structures in the new style. There

remain,

however,

a number of fine cloistered courts in

their original form, especially in

Southern

France. Among the most

remarkable of these are

those of Moissac,

Elne,

and

Montmajour.

MONUMENTS.

ITALY.

(For basilicas and domical

churches of 6th-12th centuries

see pp.

118,

119.)--Before 11th century: Sta.

Maria at Toscanella, altered 1206; S.

Donato,

Zara;

chapel at Friuli; baptistery at

Boella. 11th century: S. Giovanni,

Viterbo; Sta. Maria

della

Pieve, Arezzo; S. Antonio,

Piacenza, 1014; Eremiti, 1132, and La

Martorana,

1143,

both at Palermo; Duomo at

Bari, 1027 (much altered);

Duomo and baptistery,

Novara,

1030; Duomo at Parma, begun 1058;

Duomo at Pisa, 10631118; S.

Miniato,

Florence,

106312th century; S. Michele at

Pavia and Duomo at Modena,

late 11th

century.--12th

century: in Calabria and

Apulia, cathedrals of Trani, 1100;

Caserta,

Vecchia,

11001153; Molfetta, 1162; Benevento;

churches S. Giovanni at

Brindisi,

S.

Niccolo at Bari, 1139. In Sicily,

Duomo at Monreale, 11741189. In

Northern Italy,

S.

Tomaso in Limine, Bergamo, 1100

(?); Sta. Giulia, Brescia;

S. Lorenzo, Milan,

rebuilt

1119;

Duomo at Piacenza, 1122; S. Zeno at

Verona, 1139; S. Ambrogio, Milan,

1140,

vaulted

in 13th century; baptistery at Pisa,

11531278; Leaning Tower, Pisa,

1174.--

14th

century: S. Michele, Lucca, 1188; S.

Giovanni and S. Frediano,

Lucca. In Dalmatia,

cathedral

at Zara, 11921204. Many castles and

early town-halls, as at Bari,

Brescia,

Lucca,

etc.

FRANCE:

Previous to 11th century: St.

Germiny-des-Prés, 806, Chapel of the

Trinity, St.

Honorat-des-Lérins;

Ste. Croix de Montmajour.--11th

century: Cérisy-la-Forêt and

abbey

church

of Mont St. Michel, 1020 (the

latter altered in 12th and 16th

centuries); Vignory;

St.

Genou; porch of St.

Bénoit-sur-Loire, 1030; St. Sépulchre at

Neuvy, 1045; Ste.

Trinité

(Abbaye aux Dames) at Caen,

1046, vaulted 1140; St. Etienne

(Abbaye aux

Hommes)

at Caen, same date; St.

Front at Perigueux, 1120; Ste.

Croix at Quimperlé,

1081;

cathedral, Cahors, 10501110; abbey

churches of Cluny (demolished)

and

Vézelay,

10891100; circular church of

Rieux-Mérinville, church of St.

Savin in

Auvergne,

the churches of St. Paul at

Issoire and Notre-Dame-du-Port at

Clermont, St.

Hilaire

and Notre-Dame-la-Grande at Poitiers;

also St. Sernin (Saturnin)

at Toulouse, all at

close

of 11th and beginning of 12th

century.--12th century: Domical

churches of

Aquitania

and vicinity; Solignac and

Fontévrault, 1120; St. Etienne

(Périgueux), St.

Avit-

Sénieur;

Angoulême, Souillac, Broussac,

etc., early 12th century;

St. Trophime at

Arles,

1110,

cloisters later; church of

Vaison; abbeys and cloisters

at Montmajour, Tarascon,

Moissac

(with fragments of a 10th-century

cloister built into present

arcades); St. Paul-

du-Mausolée;

Puy-en-Vélay, with fine church. Many

other abbeys, parish

churches, and a

few

cathedrals in Central and

Northern France

especially.

18.

See

Appendix

B.

et

seq.;

also de Verneilh, L'Architecture

byzantine en France.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTUREâContinued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÃAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTUREâContinued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTUREâContinued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÃVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÃVAL ARCHITECTURE.âContinued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALYâContinued:BRAMANTEâS WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.