|

SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE |

| << BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS |

| EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE >> |

CHAPTER

XII.

SASSANIAN

AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE.

(ARABIAN,

MORESQUE, PERSIAN, INDIAN, AND

TURKISH.)

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Bourgoin,

Les

Arts Arabes.

Coste, Monuments

du Caire;

Monuments

modernes de la Perse.

Cunningham, Arch�ological

Survey of India.

Fergusson,

Indian

and Eastern Architecture. De

Forest, Indian

Architecture and

Ornament.

Flandin et Coste, Voyage

en Perse.

Franz-Pasha, Die

Baukunst des Islam.

Gayet,

L'Art

Arabe;

L'Art

Persan.

Girault de Prangey, Essai

sur l'architecture des

Arabes

en Espagne,

etc. Goury and Jones,

The

Alhambra.

Jacob, Jeypore

Portfolio of

Architectural

Details. Le

Bon, La

civilisation des Arabes;

Les

monuments de l'Inde.

Owen

Jones, Grammar

of Ornament.

Parvill�e, L'Architecture

Ottomane.

Prisse

d'Avennes,

L'Art

Arabe.

Texier, Description

de l'Arm�nie, la Perse,

etc.

GENERAL

SURVEY. While

the Byzantine Empire was at

its zenith, the new faith of

Islam

was conquering Western Asia

and the Mediterranean lands with a

fiery

rapidity,

which is one of the marvels of history.

The new architectural styles which

grew

up in the wake of these conquests, though

differing widely in conception and

detail

in the several countries, were yet

marked by common characteristics which

set

them

quite apart from the contemporary

Christian styles. The predominance

of

decorative

over structural considerations, a

predilection for minute

surface-ornament,

the

absence of pictures and sculpture,

are found alike in Arabic,

Persian, Turkish,

and

Indian buildings, though in varying

degree. These new styles,

however, were

almost

entirely the handiwork of artisans

belonging to the conquered races,

and

many

traces of Byzantine, and even

after the Crusades, of Norman and

Gothic

design,

are recognizable in Moslem

architecture. But the Orientalism of

the

conquerors

and their common faith, tinged with the

poetry and philosophic

mysticism

of the Arab, stamped these

works of Copts, Syrians, and

Greeks with an

unmistakable

character of their own, neither Byzantine

nor Early Christian.

ARABIC

ARCHITECTURE. In the

building of mosques and tombs,

especially at

Cairo,

this architecture reached a remarkable

degree of decorative elegance,

and

sometimes

of dignity. It developed slowly, the Arabs not

being at the outset a race

of

builders.

The early monuments of Syria and

Egypt were insignificant, and the

sacred

Kaabah

at

Mecca and the mosque at Medina hardly

deserve to be called

architectural

monuments

at all. The most important early

works were the mosques of

'Amrou

at

Cairo

(642, rebuilt and enlarged early in the

eighth century), of El

Aksah on

the

Temple

platform at Jerusalem (691, by

Abd-el-Melek), and of El

Walid at

Damascus

(705732,

recently seriously injured by

fire). All these were simple

one-storied

structures,

with flat wooden roofs carried on

parallel ranges of columns

supporting

pointed

arches, the arcades either

closing one side of a square

court, or surrounding

it

completely. The long perspectives of the

aisles and the minute decoration of

the

archivolts

and ceilings alone gave them

architectural character. The beautiful

Dome

of

the Rock (Kubbet-es-Sakhrah,

miscalled the Mosque of Omar) on the

Temple

platform

at Jerusalem is either a remodelled

Constantinian edifice, or in large

part

composed

of the materials of one.

FIG.

80.--MOSQUE OF SULTAN HASSAN,

CAIRO: SANCTUARY.

a,

Mihr�b, b, Mimber.

The

splendid mosque of Ibn

Touloun (876885)

was built on the same plan as that

of

Amrou, but with cantoned piers instead of

columns and a corresponding

increase

in

variety of perspective and richness of

effect. With the incoming of the

Fatimite

dynasty,

however, and the foundation of the

present city of Cairo (971),

vaulting

began

to take the place of wooden

ceilings, and then appeared the germs of

those

extraordinary

applications of geometry to decorative

design which were henceforth

to

be

the most striking feature of

Arabic ornament. Under the Ay�b dynasty,

which

began

with Sal�h-ed-din (Saladin) in 1172,

these elements, of which the

great

Barkouk

mosque

(1149) is the most imposing early

example, developed slowly in the

domical

tombs of the Karafah

at

Cairo, and prepared the way for the

increasing

richness

and splendor of a long series of

mosques, among which those of

Kalaoun

(12841318),

Sultan

Hassan (1356),

El

Mu'ayyad (1415), and

Ka�d

Bey (1463),

were

the most conspicuous examples

(Fig. 80). They mark, indeed,

successive

advances

in complexity of planning, ingenuity of

construction, and elegance of

decoration.

Together they constitute an epoch in

Arabic architecture, which

coincides

closely

with the development of Gothic vaulted

architecture in Europe, both in

the

stages

and the duration of its

advances.

The

mosques of these three

centuries are, like the

medi�val monasteries,

impressive

aggregations

of buildings of various sorts

about a central court of ablutions.

The

tomb

of the founder, residences for the

imams, or

priests, schools (madrassah),

and

hospitals

(m�rist�n) rival in

importance the prayer-chamber. This

last is, however,

the

real focus of interest and

splendor; in some cases, as in

Sultan Hassan, it is a

simple

barrel-vaulted chamber open to the

court; in others an oblong

arcaded hall

with

many small domes; or again, a

square hall covered with a high pointed

dome on

pendentives

of intricately beautiful stalactite-work

(see below). The

ceremonial

requirements

of the mosque were simple.

The-court must have its fountain

of

ablutions

in the centre. The prayer-hall, or mosque

proper, must have its

mihr�b,

or

niche,

to indicate the kibleh, the

direction of Mecca; and its

mimber, or

high, slender

pulpit

for the reading of the K�ran. These

were the only absolutely

indispensable

features

of a mosque, but as early as the ninth

century the minaret

was

added, from

which

the call to prayer could be

sounded over the city by the mueddin. Not until

the

Ayubite

period, however, did it begin to

assume those forms of varied

and

picturesque

grace which lend to Cairo so much of

its architectural

charm.

ARCHITECTURAL

DETAILS. While

Arabic architecture, in Syria and

Egypt alike,

possesses

more decorative than constructive

originality, the beautiful forms of

its

domes,

pendentives, and minarets, the simple

majesty of the great pointed

barrel-

vaults

of the Hassan mosque and similar

monuments, and the graceful lines of

the

universally

used pointed arch, prove the

Coptic builders and their later

Arabic

successors

to have been architects of

great ability. The Arabic

domes, as seen both in

the

mosques and in the remarkable group of

tombs commonly called "tombs of

the

Khal�fs,"

are peculiar not only in their

pointed outlines and their rich

external

decoration

of interlaced geometric motives, but

still more in the external and

internal

treatment

of the pendentives, exquisitely decorated

with stalactite ornament.

This

ornament,

derived, no doubt, from a combination of

minute corbels with rows of

small

niches, and presumably of Persian

origin, was finally developed into a

system

of

extraordinary intricacy, applicable

alike to the topping of a niche or

panel, as in

the

great doorways of the mosques, and to the

bracketing out of minaret

galleries

(Figs.

81, 82).

Its applications show a bewildering

variety of forms and an

extraordinary

aptitude for intricate geometrical

design.

DECORATION.

Geometry,

indeed, vied with the love of

color in its hold on the

Arabic

taste. Ceiling-beams were

carved into highly ornamental forms

before

receiving

their rich color-decoration of red,

green, blue, and gold. The

doors and the

mimber

were

framed in geometric patterns with

slender intersecting bars

forming

complicated

star-panelling. The voussoirs of arches

were cut into curious

interlocking

forms;

doorways and niches were

covered with stalactite corbelling, and

pavements

and

wall-incrustations, whether of marble or

tiling, combined brilliancy and

harmony

of

color with the perplexing beauty of

interlaced star-and-polygon patterns

of

marvellous

intricacy. Stained glass

added to the interior color-effect, the

patterns

being

perforated in plaster, with a bit of

colored glass set into each

perforation--

a

device not very durable, perhaps, but

singularly decorative.

FIG.

81.--MOSQUE OF KA�D BEY,

CAIRO.

OTHER

WORKS. Few

of the medi�val Arabic palaces

have remained to our

time.

That

they were adorned with a splendid

prodigality appears from

contemporary

accounts.

This splendor was internal

rather than external; the palace,

like all the

larger

and richer dwellings in the East,

surrounded one or more

courts, and

presented

externally an almost unbroken wall. The

fountain in the chief court, the

diw�n

(a

great, vaulted reception-chamber

opening upon the court and raised

slightly

above

it), the d�r, or

men's court, rigidly

separated from the hareem

for the

women,

were

and are universal elements in

these great dwellings. The

more common city-

houses

show as their most striking features

successively corbelled-out stories

and

broad

wooden eaves, with lattice-screens

covering single windows, or

almost a whole

fa�ade,

composed of turned work (mashrabiyya), in

designs of great

beauty.

The

fountains, gates, and minor works of the

Arabs display the same

beauty in

decoration

and color, the same general

forms and details which characterize

the

larger

works, but it is impossible here to

particularize further with regard to

them.

FIG.

82.--MOORISH DETAIL,

ALHAMBRA.

Showing

stalactite and perforated

work, Moorish cusped arch,

Hispano-Moresque capitals,

and

decorative inscriptions.

MORESQUE.

Elsewhere

in Northern Africa the Arabs produced no

such important

works

as in Egypt, nor is the architecture of the

other Moslem states so

well

preserved

or so well known. Constructive design would

appear to have been

there

even

more completely subordinated to

decoration; tiling and plaster-relief

took the

place

of more architectural elements and

materials, while horseshoe and

cusped

arches

were substituted for the simpler and

more architectural pointed

arch (Fig. 82).

The

courts of palaces and public

buildings were surrounded by

ranges of horseshoe

arches

on slender columns; these

last being provided with

capitals of a form rarely

seen

in Cairo. Towers were built of much

more massive design than the

Cairo

minarets,

usually with a square, almost

solid shaft and a more open

lantern at the

top,

sometimes in several diminishing

stories.

HISPANO-MORESQUE.

The

most splendid phase of this

branch of Arabic

architecture

is found not in Africa but in Spain, which

was overrun in 710713 by

the

Moors, who established there the

independent Khalifate of Cordova.

This was

later

split up into petty kingdoms, of which the

most important were

Granada,

Seville,

Toledo, and Valencia. This

dismemberment of the Khalifate led in

time to the

loss

of these cities, which were

one by one recovered by the

Christians during the

fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries; the capture of

Granada, in 1492, finally

destroying

the Moorish rule.

The

dominion of the Moors in Spain

was marked by a high civilization and

an

extraordinary

activity in building. The style they

introduced became the

national

style

in the regions they occupied, and even

after the expulsion of the Moors

was

used

in buildings erected by Christians and by

Jews. The "House of Pilate,"

at

Seville,

is an example of this, and the general

use of the Moorish style in

Jewish

synagogues,

down to our own day, both in Spain and abroad,

originated in the

erection

of synagogues for the Jews in Spain by

Moorish artisans and in

Moorish

style,

both during and after the period of

Moslem supremacy.

Besides

innumerable mosques, castles,

bridges, aqueducts, gates, and

fountains, the

Moors

erected several monuments of

remarkable size and magnificence.

Specially

worthy

of notice among them are the

Great Mosque at Cordova, the

Alcazars of

Seville

and Malaga, the Giralda at Seville, and

the Alhambra at Granada.

FIG.

83.--INTERIOR OF THE GREAT

MOSQUE AT CORDOVA.

The

Mosque

at Cordova,

begun in 786 by `Abd-er-Rahman, enlarged

in 876, and

again

by El Mansour in 976, is a vast arcaded hall 375

feet � 420 feet in

extent,

but

only 30 feet high (Fig. 83). The rich

wooden ceiling rests upon

seventeen rows of

thirty

to thirty-three columns each, and two

intersecting rows of piers, all

carrying

horseshoe

arches in two superposed ranges, a

large portion of those about

the

sanctuary

being cusped, the others

plain, except for the alternation of

color in the

voussoirs.

The mihr�b

niche

is particularly rich in its minutely

carved incrustations

and

mosaics, and a dome ingeniously

formed by intersecting ribs

covers the

sanctuary

before it. This form of dome occurs

frequently in Spain.

The

Alcazars

at

Seville and Malaga, which have

been restored in recent

years,

present

to-day a fairly correct counterpart of

the castle-palaces of the

thirteenth

century.

They display the same general

conceptions and decorative features as

the

Alhambra,

which they antedate. The Giralda

at

Seville is, on the other hand,

unique.

It

is a lofty rectangular tower, its

exterior panelled and covered with a

species of

quarry-ornament

in relief; it terminated originally in

two or three diminishing

stages

or

lanterns, which were replaced in the

sixteenth century by the present

Renaissance

belfry.

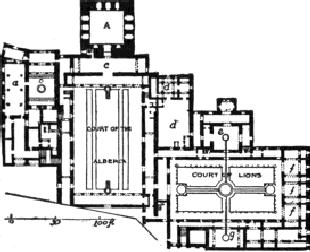

FIG.

84.--PLAN OF THE

ALHAMBRA.

A,

Hall of Ambassadors; a, Mosque; b,

Court of Mosque; c, Sala

della Barca; d, d,

Baths;

e,

Hall of the Two Sisters; f, f, f,

Hall of the Tribunal; g,

Hall of the

Abencerrages.

The

Alhambra

is

universally considered to be the

masterpiece of Hispano-Moresque

art,

partly no doubt on account of its

excellent preservation. It is most

interesting as

an

example of the splendid citadel-palaces

built by the Moorish conquerors, as

well

as

for its gorgeous color-decoration of

minute quarry-ornament stamped or

moulded

in

the wet plaster wherever the walls

are not wainscoted with tiles. It

was begun in

1248

by Mohammed-ben-Al-Hamar, enlarged in 1279 by

his successor, and again

in

1306,

when its mosque was built. Its plan

(Fig. 84) shows two large

courts and a

smaller

one next the mosque, with three

great square chambers and many of

minor

importance.

Light arcades surround the

Court of the Lions with its

fountain, and

adorn

the ends of the other chief

court; and the stalactite pendentive,

rare in

Moorish

work, appears in the "Hall of Ambassadors" and

some other parts of

the

edifice.

But its chief glory is its

ornamentation, less durable,

less architectural than

that

of the Cairene buildings, but making up

for this in delicacy and richness.

Minute

vine-patterns

and Arabic inscriptions are

interwoven with waving intersecting

lines,

forming

a net-like framework, to all of which

deep red, blue, black, and

gold give an

indescribable

richness of effect.

The

Moors also overran Sicily in

the eighth century, but while their

architecture there

profoundly

influenced that of the Christians who

recovered Sicily in 1090, and

copied

the style of the conquered Moslems,

there is too little of the original

Moorish

architecture

remaining to claim mention

here.

SASSANIAN.

The

Sassanian empire, which during the four

centuries from 226 to

641

A.D. had withstood Rome and extended

its own sway almost to India, left

on

Persian

soil a number of interesting monuments

which powerfully influenced the

Mohammedan

style of that region. The Sassanian

buildings appear to have

been

principally

palaces, and were all vaulted. With their

long barrel-vaulted

halls,

combined

with square domical chambers, as in

Firouz-Abad and Serbistan, they

exhibit

reminiscences of antique Assyrian

tradition. The ancient Persian

use of

columns

was almost entirely

abandoned, but doors and windows

were still treated

with

the banded frames and cavetto-cornices of

Persepolis and Susa. The

Sassanians

employed

with these exterior details

others derived perhaps from

Syrian and

Byzantine

sources. A sort of engaged

buttress-column and blind arches

repeated

somewhat

aimlessly over a whole fa�ade

were characteristic features;

still more so

the

huge arches, elliptical or

horse-shoe shaped, which formed the

entrances to these

palaces,

as in the T�k-Kesra at Ctesiphon.

Ornamental details of a debased

Roman

type

appear, mingled with more

gracefully flowing leaf-patterns

resembling early

Christian

Syrian carving. The last

great monument of this style was the

palace at

Mashita

in Moab, begun by the last Chosroes

(627), but never finished, an

imposing

and

richly ornamented structure about 500 �

170 feet, occupying the centre of

a

great

court.

PERSIAN-MOSLEM

ARCHITECTURE. These

Sassanian palaces must have

strongly

influenced

Persian architecture after the

Arab conquest in 641. For

although the

architecture

of the first six centuries

after that date suffered

almost absolute

extinction

at the hands of the Mongols under Genghis

Khan, the traces of Sassanian

influence

are still perceptible in the

monuments that rose in the following

centuries.

The

dome and vault, the colossal

portal-arches, and the use of brick and

tile are

evidences

of this influence, bearing no resemblance

to Byzantine or Arabic types.

The

Moslem

monuments of Persia, so far as their

dates can be ascertained,

are all

subsequent

to 1200, unless tradition is correct in

assigning to the time of Haroun Ar

Rashid

(786) certain curious tombs

near Bagdad with singular

pyramidal roofs. The

ruined

mosque at Tabriz (1300), and the

beautiful domical Tomb

at

Sultaniyeh

(1313)

belong to the Mogul period. They show all the

essential features of the

later

architecture

of the Sufis (14991694), during

whose dynastic period were

built the

still

more splendid and more

celebrated Meidan

or

square, the great mosque

of

Mesjid

Shah, the Bazaar and the College or

Medress of Hussein Shah, all at

Ispahan,

and

many other important monuments at

Ispahan, Bagdad, and Teheran. In

these

structures

four elements especially claim

attention; the pointed bulbous

dome, the

round

minaret, the portal-arch rising

above the adjacent portions of the

building, and

the

use of enamelled terra-cotta

tiles as an external decoration. To

these may be

added

the ogee arch (ogee

=

double-reversed curve), as an occasional

feature. The

vaulting

is most ingenious and beautiful, and

its forms, whether executed

in brick or

in

plaster, are sufficiently

varied without resort to the perplexing

complications of

stalactite

work. In Persian decoration the most

striking qualities are the harmony

of

blended

color, broken up into minute patterns and

more subdued in tone than in

the

Hispano-Moresque,

and the preference of flowing lines and

floral ornament to the

geometric

puzzles of Arabic design.

Persian architecture influenced both

Turkish and

Indo-Moslem

art, which owe to it a large part of their

decorative charm.

INDO-MOSLEM.

The

Mohammedan architecture of India is so

distinct from all the

native

Indian styles and so related to the art of

Persia, if not to that of the

Arabs,

that

it properly belongs here

rather than in the later chapter on

Oriental styles. It

was

in the eleventh century that the states of India

first began to fall

before

Mohammedan

invaders, but not until the end of the

fifteenth century that the great

Mogul

dynasty was established in

Hindostan as the dominant power. During

the

intervening

period local schools of

Moslem architecture were

developing in the

Pathan

country of Northern India (11931554), in Jaunpore and

Gujerat (1396

1572),

in Scinde, where Persian

influence predominated; in Kalburgah and

Bidar

(13471426).

These schools differed

considerably in spirit and detail; but

under the

Moguls

(14941706) there was less

diversity, and to this dynasty we owe

many of

the

most magnificent mosques and

tombs of India, among which those of

Bijapur

retain

a marked and distinct style of their

own.

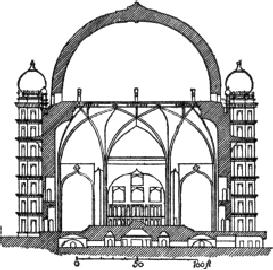

FIG.

85.--TOMB OF MAHMUD, BIJAPUR.

SECTION.

The

Mohammedan monuments of India are

characterized by a grandeur and

amplitude

of disposition, a symmetry and monumental

dignity of design which

distinguishes

them widely from the picturesque but sometimes

trivial buildings of the

Arabs

and Moors. Less dependent on

color than the Moorish or Persian

structures,

they

are usually built of marble, or of

marble and sandstone, giving them an

air of

permanence

and solidity wanting in other

Moslem styles except the Turkish.

The

dome,

the round minaret, the pointed arch, and

the colossal portal-arch,

are

universal,

as in Persia, and enamelled tiles

are also used, but chiefly

for interior

decoration.

Externally the more dignified if

less resplendent decoration of

surface

carving

is used, in patterns of minute and

graceful scrolls, leaf

forms, and Arabic

inscriptions

covering large surfaces. The

Arabic stalactite pendentive

star-panelling

and

geometrical interlace are

rarely if ever seen. The

dome on the square plan is

almost

universal, but neither the Byzantine nor

the Arabic pendentive is

used,

striking

and original combinations of vaulting

surfaces, of corner squinches,

of

corbelling

and ribs, being used in its

place. Many of the Pathan domes and

arches at

Delhi,

Ajmir, Ahmedabad, Shepree, etc.,

are built in horizontal or corbelled

courses

supported

on slender columns, and exert no thrust

at all, so that they are vaults

only

original

of all Indian domes are those of the

Jumma

Musjid and of the

Tomb

of

Mahmud, both at

Bijapur, the latter 137 feet in

span (Fig. 85). These

two

monuments,

indeed, with the Mogul Taj Mahal at Agra, not only

deserve the first

rank

among Indian monuments, but in

constructive science combined with

noble

proportions

and exquisite beauty are hardly, if at

all, surpassed by the greatest

triumphs

of western art. The Indo-Moslem

architects, moreover, especially

those of

the

Mogul period, excelled in providing

artistic settings for their

monuments.

Immense

platforms, superb courts,

imposing flights of steps,

noble gateways,

minarets

to mark the angles of enclosures, and

landscape gardening of a high

order,

enhance

greatly the effect of the great

mosques, tombs, and palaces of

Agra, Delhi,

Futtehpore

Sikhri, Allahabad, Secundra,

etc.

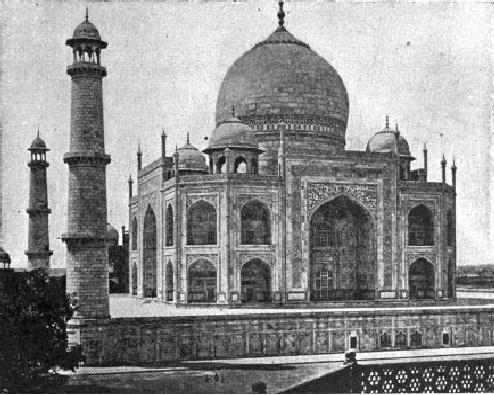

The

most notable monuments of the

Moguls are the Mosque

of Akbar (15561605)

at

Futtehpore Sikhri, the tomb of that

sultan at Secundra, and his

palace at

Allahabad;

the Pearl

Mosque at

Agra and the Jumma

Musjid at

Delhi, one of the

largest

and noblest of Indian mosques, both built by

Shah Jehan about 1650;

his

immense

but now ruined palace in the same city;

and finally the unrivalled

mausoleum,

the Taj

Mahal at

Agra, built during his

lifetime as a festal hall, to

serve

as

his tomb after death (Fig.

86). This last is the pearl of Indian

architecture, though

it

is said to have been

designed by a European architect,

French or Italian. It is a

white

marble structure 185 feet

square, centred in a court 313 feet

square, forming

a

platform 18 feet high. The

corners of this court are marked by

elegant minarets,

and

the whole is dominated by the exquisite

white marble dome, 58 feet in

diameter,

80

feet high, internally rising

over four domical corner

chapels, and covered

externally

by a lofty marble bulb-dome on a high drum. The rich

materials, beautiful

execution,

and exquisite inlaying of this mausoleum

are worthy of its majestic

design.

On

the whole, in the architecture of the

Moguls in Bijapur, Agra, and

Delhi,

Mohammedan

architecture reaches its

highest expression in the totality and

balance

of

its qualities of construction,

composition, detail, ornament, and

settings. The later

monuments

show the decline of the style, and though

often rich and imposing,

are

lacking

in refinement and originality.

FIG.

86.--TAJ MAHAL, AGRA.

TURKISH.

The Ottoman

Turks, who began their conquering career

under Osman I.

in

Bithynia in 1299, had for a century been

occupying the fairest portions of

the

Byzantine

empire when, in 1453, they became masters

of Constantinople. Hagia

Sophia

was at once occupied as

their chief mosque, and such

of the other churches as

were

spared, were divided between

the victors and the vanquished. The

conqueror,

Mehmet

II., at the same time set

about the building of a new mosque,

entrusting the

design

to a Byzantine, Christodoulos, whom he

directed to reproduce, with

some

modifications,

the design of the "Great Church"--Hagia

Sophia. The type thus

officially

adopted has ever since

remained the controlling model of Turkish

mosque

design,

so far, at least, as general plan and

constructive principles are

concerned.

Thus

the conquering Turks, educated by a

century of study and imitation of

Byzantine

models in Brusa, Nicomedia,

Smyrna, Adrianople, and other

cities earlier

subjugated,

did what the Byzantines had, during

nine centuries, failed to

do. The

noble

idea first expressed by

Anthemius and Isidorus in the Church of

Hagia Sophia

had

remained undeveloped, unimitated by

later architects. It was the Turk who

first

seized

upon its possibilities, and developed

therefrom a style of architecture

less

sumptuous

in color and decoration than the sister

styles of Persia, Cairo, or

India,

but

of great nobility and dignity,

notwithstanding. The low-curved dome with

its

crown

of buttressed windows, the plain

spherical pendentives, the great

apses at

each

end, covered by half-domes and

penetrated by smaller niches, the four

massive

piers

with their projecting buttress-masses

extending across the broad

lateral aisles,

the

narthex and the arcaded atrium in front--all

these appear in the great

Turkish

mosques

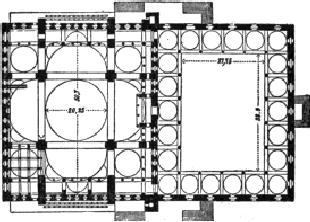

of Constantinople. In the Conqueror's

mosque, however, two apses

with

half-domes

replace the lateral galleries and

clearstory of Hagia Sophia,

making a

perfectly

quadripartite plan, destitute of the

emphasis and significance of a

plan

drawn

on one main axis (Fig. 87). The

same treatment occurs in the

mosque of

Ahmed

I., the Ahmediyeh

(1608;

Fig. 88), and the Yeni

Djami ("New

Mosque") at

the

port (1665). In the mosque of Osman

III. (1755) the

reverse change was

effected;

the mosque has no great

apses, four clearstories filling the four

arches

under

the dome, as also in several of the

later and smaller mosques. The

greatest and

noblest

of the Turkish mosques, the Suleimaniyeh, built in

1553 by Soliman the

Magnificent,

returned to the Byzantine combination of

two half-domes with two

clearstories

(Fig. 89).

FIG.

87.--MOSQUE OF MEHMET II., CONSTANTINOPLE.

PLAN.

(The

dimensions figured in

metres.)

In

none of these monuments is

there the internal magnificence of

marble and mosaic

of

the Byzantine churches. These

are only in a measure replaced by

Persian tile-

wainscoting

and stained-glass windows of the Arabic

type. The division into

stories

and

the treatment of scale are

less well managed than in the Hagia

Sophia; on the

other

hand, the proportion of height to width is

generally admirable. The

exterior

treatment

is unique and effective, far superior to

the Byzantine practice. The

massing

of

domes and half-domes and roofs is

more artistically arranged; and while

there is

little

of that minute carved detail found in

Egypt and India, the composition of

the

lateral

arcades, the simple but impressive

domical peristyles of the courts, and

the

graceful

forms of the pointed arches, with

alternating voussoirs of white and

black

marble,

are artistic in a high degree. The

minarets are, however,

inferior to those of

Indian,

Persian, and Arabic art, though graceful

in their proportions.

Nearly

all the great mosques are

accompanied by the domical tombs

(turbeh) of

their

imperial

founders. Some of these are

of noble size and great

beauty of proportion and

decoration.

The Tomb

of Roxelana (Khourrem),

the favorite wife of Soliman the

Magnificent

(1553), is the most beautiful of all, and

perhaps the most perfect gem

of

Turkish

architecture, with its elegant

arcade surrounding the octagonal

domical

mausoleum-chamber.

The monumental

fountains of

Constantinople also

deserve

mention.

Of these, the one erected by Ahmet III.

(1710), near Hagia Sophia, is

the

most

beautiful. They usually consist of a

rectangular marble reservoir with

pagoda-

like

roof and broad eaves, the four

faces of the fountain adorned each with a

niche

and

basin, and covered with relief

carving and gilded

inscriptions.

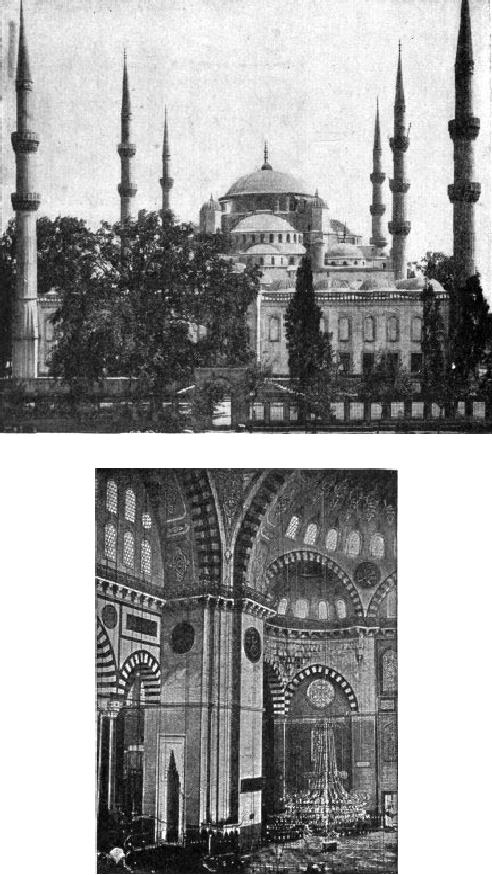

FIG.

88.--EXTERIOR AHMEDIYEH

MOSQUE.

FIG.

89.--INTERIOR OF SULEIMANIYEH,

CONSTANTINOPLE.

PALACES.

In this

department the Turks have done little of

importance. The

buildings

in the Seraglio gardens are low and

insignificant. The Tchinli

Kiosque,

now

the

Imperial Museum, is however, a simple but

graceful two-storied

edifice,

consisting

of four vaulted chambers in the angles of

a fine cruciform hall, with

domes

treated

like those of Bijapur on a

small scale; the tiling and the

veranda in front are

particularly

elegant; the design suggests

Persian handiwork. The later

palaces,

designed

by Armenians, are picturesque white

marble and stucco buildings on

the

water's

edge; they possess richly decorated

halls, but the details are of a

debased

European

rococo style, quite unworthy of an

Oriental monarch.

MONUMENTS.

ARABIAN:

"Mosque of Omar," or Dome of the

Rock, 638; El Aksah, by

'Abd-el-Melek,

691, both at Jerusalem; Mosque

'Amrou at Cairo, 642; mosques

at

Cyrene,

665; great mosque of El Wal�d,

Damascus, 705717. Bagdad built, 755.

Great

mosque

at Kairou�n, 737. At Cairo, Ibn Touloun,

876; Gama-El-Azhar, 971; Barkouk,

1149;

"Tombs of Khal�fs" (Karafah),

12501400; Moristan Kalaoun, 1284;

Medresseh

Sultan

Hassan, 1356; El Azhar enlarged; El

M�ayed, 1415; Ka�d Bey, 1463;

Sinan

Pacha,

1468; "Tombs of Mamelukes," 16th century.

Also palaces, baths,

fountains,

mosques,

and tombs. MORESQUE: Mosque at Saragossa, 713;

mosque and arsenal at

Tunis,

742; great mosque at Cordova, 786, 876,

975; sanctuary, 14th century.

Mosques,

baths, etc., at Cordova,

Tarragona, Segovia, Toledo, 960980;

mosque of

Sobeiha

at Cordova, 981. Palaces and

mosques at Fez; great mosque

at Seville, 1172.

Extensive

building in Morocco close of 12th

century. Giralda at Seville, 1160;

Alcazars in

Malaga

and Seville, 12251300; Alhambra

and Generalife at Granada, 1248,

1279,

1306;

also mosques, baths, etc.

Yussuf builds palace at

Malaga, 1348; palaces at

Granada.

PERSIAN: Tombs near Bagdad, 786

(?); mosque at Tabriz, 1300;

tomb of

Khodabendeh

at Sultaniyeh, 1313; Meidan Shah

(square) and Mesjid Shah

(mosque) at

Ispahan,

17th century; Medresseh (school) of

Sultan Hussein, 18th century;

palaces of

Chehil

Soutoun (forty columns) and

Aineh Khaneh (Palace of

Mirrors). Baths,

tombs,

bazaars,

etc., at Cashan, Koum,

Kasmin, etc. Aminabad

Caravanserai between Shiraz

and

Ispahan;

bazaar at Ispahan.

INDIAN:

Mosque and "Kutub Minar"

(tower) cir.

1200; Tomb of

Altumsh, 1236; mosque

at

Ajmir, 12111236; tomb at Old Delhi;

Adina Mosque, Maldah, 1358.

Mosques

Jumma

Musjid and Lal Durwaza at

Jaunpore, first half of 15th

century. Mosque and

bazaar,

Kalburgah, 1435 (?). Mosques at

Ahmedabad and Sirkedj,

middle 15th century.

Mosque

Jumma Musjid and Tomb of

Mahm�d, Bijapur, cir.

1550. Tomb of

Humay�n,

Delhi;

of Mohammed Ghaus, Gwalior;

mosque at Futtehpore Sikhri;

palace at Allahabad;

tomb

of Akbar at Secundra, all by

Akbar, 15561605. Palace and

Jumma Musjid at

Delhi;

Muti Musjid (Pearl mosque)

and Taj Mahal at Agra, by

Shah Jehan, 16281658.

TURKISH:

Tomb of Osman, Brusa, 1326; Green

Mosque (Yeshil Djami) Brusa,

cir.

1350.

Mosque

at Isnik (Nic�a), 1376. Mehmediyeh

(mosque Mehmet II.)

Constantinople,

1453;

mosque at Eyoub; Tchinli

Kiosque, by Mehmet II., 145060;

mosque Bayazid,

1500;

Selim I., 1520; Suleimaniyeh, by Sinan,

1553; Ahmediyeh by Ahmet I., 1608;

Yeni

Djami, 1665; Nouri Osman, by

Osman III., 1755; mosque Mohammed Ali in

Cairo,

1824.

Mosque at Adrianople. KHANS, cloistered courts for

public business and

commercial

lodgers, various dates, 16th

and 17th centuries (Valid�

Khan, Vizir Khan),

vaulted

bazaars, fountains, Seraskierat

Tower, all at

Constantinople.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.