|

BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS |

| << EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA |

| SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE >> |

CHAPTER

XI.

BYZANTINE

ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Essenwein,

H�bsch, Von Quast. Also,

Bayet, L'Art

Byzantin.

Choisy, L'Art

de b�tir chez les

Byzantins.

Lethaby and Swainson,

Sancta

Sophia.

Ongania, La

Basilica di San Marco.

Pulgher, Anciennes

�glises Byzantines de

Constantinople.

Salzenberg, Altchristliche

Baudenkm�le von

Constantinopel.

Texier and

Pullan,

Byzantine

Architecture.

ORIGIN

AND CHARACTER. The

decline and fall of Rome arrested the

development

of

the basilican style in the West, as did

the Arab conquest later in

Syria. It was

otherwise

in the new Eastern capital founded by

Constantine in the ancient

Byzantium,

which was rising in power and wealth

while Rome lay in ruins.

Situated

at

the strategic point of the natural highway of

commerce between East and

West,

salubrious

and enchantingly beautiful in its

surroundings, the new capital

grew

rapidly

from provincial insignificance to

metropolitan importance. Its founder

had

embellished

it with an extraordinary wealth of

buildings, in which, owing to the

scarcity

of trained architects, quantity and cost

doubtless outran quality. But at

least

the

tameness of blindly followed precedent

was avoided, and this departure

from

traditional

tenets contributed

undoubtedly to the originality

of Byzantine

architecture.

A large part of the artisans employed in

building were then, as now,

from

Asia Minor and the �gean Islands,

Greek in race if not in name. An

Oriental

taste

for brilliant and harmonious color and

for minute decoration spread over

broad

surfaces

must have been stimulated by

trade with the Far East and by

constant

contact

with Oriental peoples, costumes, and

arts. An Asiatic origin may

also be

assigned

to the methods of vaulting employed, far

more varied than the Roman,

not

only

in form but also in materials and

processes. From Roman

architecture, however,

the

Byzantines borrowed the fundamental

notion of their structural art; that,

namely,

of

distributing the weights and strains of

their vaulted structures upon isolated

and

massive

points of support, strengthened by

deep buttresses, internal or

external, as

the

case might be. Roman,

likewise, was the use of

polished monolithic columns,

and

the

incrustation of the piers and walls with

panels of variegated marble, as well

as

the

decoration of plastered surfaces by

fresco and mosaic, and the use of

opus

sectile

and

opus

Alexandrinum for the

production of sumptuous marble

pavements. In the

first

of these processes the color-figures of

the pattern are formed each

of a single

piece

of marble cut to the shape required; in

the second the pattern is

compounded

of

minute squares, triangles, and curved

pieces of uniform size. Under

these

combined

influences the artists of Constantinople

wrought out new problems in

construction

and decoration, giving to all that they

touched a new and striking

character.

There

is no absolute line of demarcation,

chronological, geographical, or

structural,

between

Early Christian and Byzantine

architecture. But the former was

especially

characterized

by the basilica with three or five

aisles, and the use of wooden

roofs

even

in its circular edifices; the vault and

dome, though not unknown, being

exceedingly

rare. Byzantine architecture, on the

other hand, rarely produced

the

simple

three-aisled or five-aisled basilica, and

nearly all its monuments

were vaulted.

The

dome was especially

frequent, and Byzantine architecture

achieved its highest

triumphs

in the use of the pendentive, as the

triangular spherical surfaces

are called,

by

the aid of which a dome can be

supported on the summits of four arches

spanning

the

four sides of a square, as explained

later. There is as little uniformity in the

plans

of

Byzantine buildings as in the forms of

the vaulting. A few types of

church-plan,

however,

predominated locally in one or

another centre; but the controlling

feature of

the

style was the dome and the

constructive system with which it was

associated.

The

dome, it is true, had long been

used by the Romans, but always on a

circular

plan,

as in the Pantheon. It is also a fact

that pendentives have been found in

Syria

and

Asia Minor older than the oldest

Byzantine examples. But the special

feature

characterizing

the Byzantine dome on pendentives

was its almost

exclusive

association

with plans having piers and

columns or aisles, with the dome as

the

Another

strictly Byzantine practice

was the piercing of the lower

portion of the dome

with

windows forming a circle or crown, and the final

development of this feature

into

a high drum.

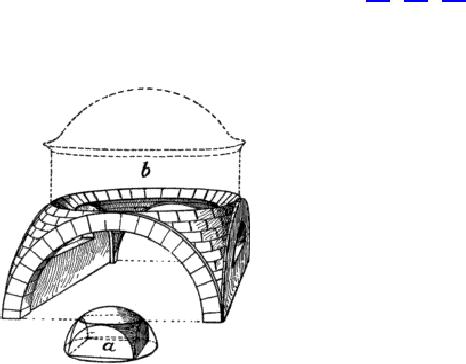

FIG.

71.--DIAGRAM OF PENDENTIVES.

CONSTRUCTION.

Still

another divergence from Roman

methods was in the

substitution

of brick and stone masonry for

concrete. Brick was used for

the mass as

well

as the facing of walls and piers, and for

the vaulting in many buildings

mainly

built

of stone. Stone was used

either alone or in combination with

brick, the latter

appearing

in bands of four or five courses at

intervals of three or four feet. In

later

work

a regular alternation of the two

materials, course for course,

was not

uncommon.

In piers intended to support unusually

heavy loads the stone was

very

carefully

cut and fitted, and sometimes tied and

clamped with iron.

Vaults

were built sometimes of brick,

sometimes of cut stone; in a few cases

even of

earthenware

jars fitting into each other, and

laid up in a continuous

contracting

spiral

from the base to the crown of a dome, as in

San Vitale at Ravenna.

Ingenious

processes

for building vaults without centrings

were made use

of--processes

inherited

from the drain-builders of ancient

Assyria, and still in vogue in

Armenia,

Persia,

and Asia Minor. The groined vault was

common, but always

approximated

the

form of a dome, by a longitudinal

convexity upward in the intersecting

vaults.

DOMES.

The

dome, as we have seen, early

became the most characteristic

feature of

Byzantine

architecture; and especially the dome on

pendentives. If a hemisphere be

cut

by five planes, four perpendicular to

its base and bounding a

square inscribed

therein,

and the fifth plane parallel to the base

and tangent to the semicircular

intersections

made by the first four, there will

remain of the original surface

only

four

triangular spaces bounded by

arcs of circles. These are

called pendentives

(Fig.

71

a). When

these are built up of masonry,

each course forms a species

of arch, by

virtue

of its convexity. At the crown of the four

arches on which they rest,

these

courses

meet and form a complete circle,

perfectly stable and capable of

sustaining

any

superstructure that does not by excessive

weight disrupt the whole fabric

by

overthrowing

the four arches which support it. Upon

these pendentives, then, a new

dome

may be started of any desired curvature,

or even a cylindrical drum to

support

a

still loftier dome, as in the

later churches (Fig. 71

b).

This method of covering

a

square

is simpler than the groined vault, having

no sharp edges or intersections; it

is

at

least as effective architecturally, by

reason of its greater height

in the centre; and

is

equally applicable to successive

bays of an oblong, cruciform, and

even columnar

building.

In the great cisterns at Constantinople

vast areas are covered by

rows of

small

domes supported on ranges of

columns.

The

earlier domes were commonly

pierced with windows at the base, this

apparent

weakening

of the vault being compensated for by

strongly buttressing the

piers

between

the windows, as in Hagia Sophia.

Here forty windows form a crown of light

at

the spring of the dome, producing an

effect almost as striking as that of the

simple

oculus

of the

Pantheon, and celebrated by ancient

writers in the most

extravagant

terms.

In later and smaller churches a high drum

was introduced beneath the

dome,

in

order to secure, by means of

longer windows, more light than

could be obtained

by

merely piercing the diminutive

domes.

Buttressing

was well understood by the Byzantines,

whose plans were

skilfully

devised

to provide internal abutments, which

were often continued above

the roofs

of

the side-aisles to prop the main vaults,

precisely as was done by the

Romans in

their

therm� and similar halls. But the

Byzantines, while adhering less

strictly than

the

Romans to traditional forms and

processes, and displaying much more

ready

contrivance

and special adaptation of means to

ends, never worked out this

pregnant

structural

principle to its logical

conclusion as did the Gothic architects

of Western

Europe

a few centuries later.

DECORATION. The

exteriors of Byzantine buildings

(except in some of the

small

churches

of late date) were generally

bare and lacking in beauty. The

interiors, on the

contrary,

were richly decorated, color

playing a much larger part than carving

in the

designs.

Painting was resorted to only in the

smaller buildings, the more

durable and

splendid

medium of mosaic being

usually preferred. This was,

as a rule, confined to

the

vaults and to those portions of the

wall-surfaces embraced by the vaults

above

their

springing. The colors were

brilliant, the background being

usually of gold,

though

sometimes of blue or a delicate

green. Biblical scenes,

symbolic and

allegorical

figures and groups of saints

adorned the larger areas,

particularly the half-

dome

of the apse, as in the basilicas. The

smaller vaults, the soffits of

arches,

borders

of pictures, and other minor surfaces,

received a more

conventional

decoration

of crosses, monograms, and set

patterns.

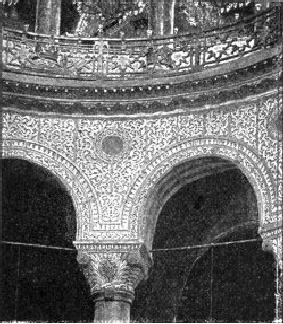

FIG.

72.--SPANDRIL. HAGIA SOPHIA.

The

walls throughout were

sheathed with slabs of rare

marble in panels so

disposed

that

the veining should produce

symmetrical figures. The panels

were framed in

billet-mouldings,

derived perhaps from classic

dentils; the billets or projections

on

one

side the moulding coming

opposite the spaces on the other. This

seems to have

been

a purely Byzantine feature.

CARVED

DETAILS. Internally the

different stories were

marked by horizontal

bands

and

cornices of white or inlaid marble richly

carved. The arch-soffits, the

archivolts

or

bands around the arches, and the

spandrils between them were

covered with

minute

and intricate incised carving. The

motives used, though based on

the

acanthus

and anthemion, were given a wholly new

aspect. The relief was low

and

flat,

the leaves sharp and crowded, and the

effect rich and lacelike, rather

than

vigorous.

It was, however, well adapted to the

covering of large areas

where general

effect

was more important than

detail. Even the capitals

were treated in the

same

spirit.

The impost-block was almost

universal, except where its

use was rendered

unnecessary

by giving to the capital itself the

massive pyramidal form required

to

receive

properly the spring of the arch or vault.

In such cases (more frequent

in

Constantinople

than elsewhere) the surface of the

capital was simply covered

with

incised

carving of foliage, basketwork,

monograms, etc.; rudimentary

volutes in a few

cases

recalling classic traditions

(Figs. 72, 73). The mouldings were

weak and poorly

executed,

and the vigorous profiles of classic

cornices were only remotely

suggested

by

the characterless aggregations of

mouldings which took their

place.

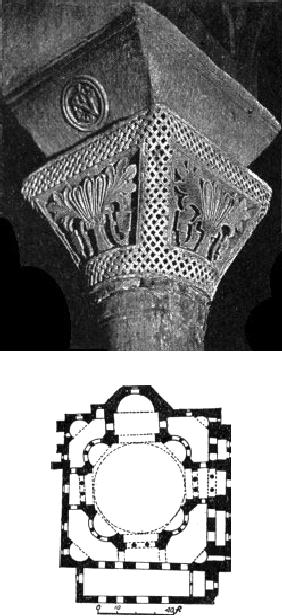

FIG.

73.--CAPITAL WITH IMPOST BLOCK, S.

VITALE.

FIG.

74.--ST. SERGIUS, CONSTANTINOPLE.

PLANS.

The

remains of Byzantine architecture

are almost exclusively of

churches and

baptisteries,

but the plans of these are

exceedingly varied. The first

radical departure

from

the basilica-type seems to have

been the adoption of circular or

polygonal plans,

such

as had usually served only for tombs and

baptisteries. The Baptistery of St.

John

at

Ravenna (early fifth century) is

classed by many authorities as a

Byzantine

monument.

In the early years of the sixth century

the adoption of this model had

become

quite general, and with it the

development of domical design

began to

advance.

The church of St.

Sergius at

Constantinople (Fig. 74), originally

joined to a

short

basilica dedicated to St.

Bacchus (afterward destroyed by the

Turks), as in the

double

church at Kelat Seman, was built

about 520; that of San

Vitale at

Ravenna

was

begun a few years later; both

are domical churches on an

octagonal plan, with

an

exterior aisle. Semicircular

niches--four in St. Sergius and

eight in San Vitale--

projecting

into the aisle, enlarge somewhat the

area of the central space and

give

variety

to the internal effect. The origin of

this characteristic feature may be traced

to

the

eight niches of the Pantheon, through

such intermediate examples as the

temple

of

Minerva Medica at Rome. The true

pendentive does not appear in

these two

churches.

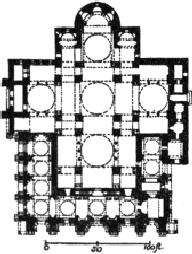

FIG.

75.--PLAN OF HAGIA SOPHIA.

Timidly

employed up to that time in small

structures, it received a

remarkable

development

in the magnificent church of Hagia

Sophia, built by

Anthemius of

Tralles

and Isodorus of Miletus, under Justinian, 532538

A.D. In the plan of this

marvellous

edifice (Fig. 75) the dome

rests upon four mighty arches bounding

a

square,

into two of which open the half-domes of

semicircular apses. These

apses are

penetrated

and extended each by two smaller

niches and a central arch, and

the

whole

vast nave, measuring over

200 � 100 feet, is flanked by enormously

wide

aisles

connecting at the front with a majestic

narthex. Huge transverse

buttresses, as

in

the Basilica of Constantine (with whose

structural design this building

shows

striking

affinities), divide the aisles

each into three sections. The plan

suggests that

of

St. Sergius cut in two, with a lofty dome

on pendentives over a square

plan

inserted

between the halves. Thus was

secured a noble and unobstructed hall

of

unrivalled

proportions and great beauty,

covered by a combination of

half-domes

increasing

in span and height as they lead up

successively to the stupendous

central

vault,

which rises 180 feet into the air and

fitly crowns the whole. The

imposing

effect

of this low-curved but loftily-poised

dome, resting as it does upon a crown

of

windows,

and so disposed that its summit is

visible from every point of the nave

(as

may

be easily seen from an examination of the

section, Fig. 76), is not surpassed

in

any

interior ever

erected.

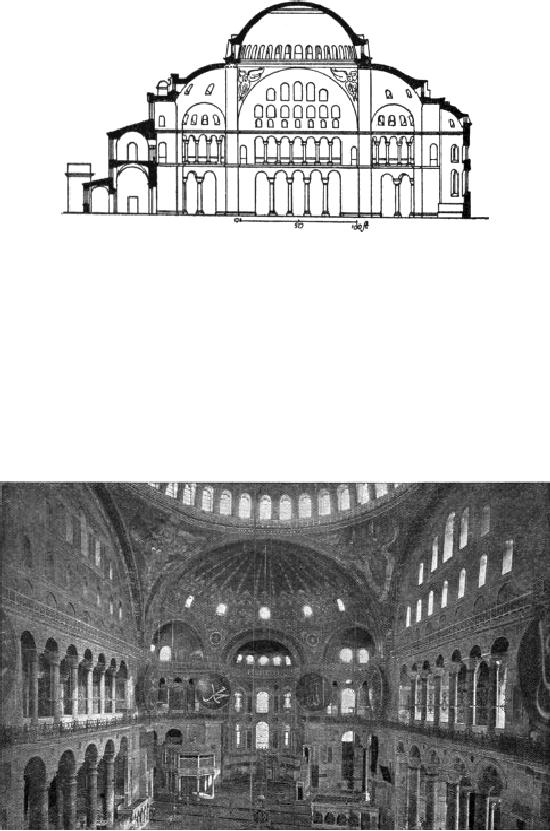

FIG.

76.--SECTION OF HAGIA SOPHIA.

The

two lateral arches under the dome

are filled by clearstory

walls pierced by

twelve

windows,

and resting on arcades in two stories

carried by magnificent columns

taken

from

ancient ruins. These

separate the nave from the side-aisles,

which are in two

stories

forming galleries, and are

vaulted with a remarkable variety of

groined vaults.

All

the masses are disposed with

studied reference to the resistance

required by the

many

and complex thrusts exerted by the

dome and other vaults. That

the

earthquakes

of one thousand three hundred and fifty

years have not destroyed

the

church

is the best evidence of the sufficiency

of these precautions.

FIG.

77.--INTERIOR OF HAGIA SOPHIA,

CONSTANTINOPLE.

Not

less remarkable than the noble

planning and construction of this church

was the

treatment

of scale and decoration in its

interior design. It was as

conspicuously the

masterpiece

of Byzantine architecture as the

Parthenon was of the classic

Greek.

With

little external beauty, it is internally

one of the most perfectly

composed and

beautifully

decorated halls of worship

ever erected. Instead of the

simplicity of the

Pantheon

it displays the complexity of an organism

of admirably related parts.

The

division

of the interior height into two stories

below the spring of the four

arches,

reduces

the component parts of the design to

moderate dimensions, so that the

scale

of

the whole is more easily grasped and

its vast size emphasized by

the contrast. The

walls

are incrusted with precious

marbles up to the spring of the vaulting;

the

capitals,

spandrils, and soffits are richly and

minutely carved with incised

ornament,

and

all the vaults covered with splendid

mosaics. Dimmed by the lapse of

centuries

and

disfigured by the vandalism of the

Moslems, this noble interior, by the

harmony

of

its coloring and its

impressive grandeur, is one of the

masterpieces of all time

(Fig.

77).

LATER

CHURCHES. After

the sixth century no monuments

were built at all rivalling

in

scale the creations of the former

period. The later churches

were, with few

exceptions,

relatively small and trivial.

Neither the plan nor the general aspect

of

Hagia

Sophia seems to have been

imitated in these later

works. The crown of dome-

windows

was replaced by a cylindrical drum under

the dome, which was usually

of

insignificant

size. The exterior was

treated more decoratively than

before, by means

of

bands and incrustations of colored

marble, or alternations of stone and

brick; and

internally

mosaic continued to be executed with

great skill and of great

beauty until

the

tenth century, when the art rapidly declined.

These later churches, of which

a

number

were spared by the Turks, are,

therefore, generally pleasing and

elegant

rather

than striking or imposing.

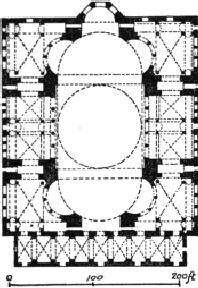

FIG.

78.--PLAN OF ST. MARK'S,

VENICE.

FOREIGN

MONUMENTS. The

influence of Byzantine art was

wide-spread, both in

Europe

and Asia. The leading city of

civilization through the Dark

Ages,

Constantinople

influenced Italy through her political and

commercial relations with

Ravenna,

Genoa, and Venice. The church of

St.

Mark in the

latter city was one

result

of

this influence (Figs. 78, 79). Begun in

1063 to replace an earlier church

destroyed

by

fire, it received through several

centuries additions not always

Byzantine in

character.

Yet it was mainly the work of Byzantine

builders, who copied

most

probably

the church of the Apostles at Constantinople, built by

Justinian. The

picturesque

but wholly unstructural use of columns in

the entrance porches, the

upper

parts of the fa�ade, the wooden

cupolas over the five domes,

and the pointed

arches

in the narthex, are deviations from

Byzantine traditions dating in part

from

the

later Middle Ages Nothing

could well be conceived more

irrational, from a

structural

point of view, than the accumulation of columns in the

entrance-arches;

but

the total effect is so picturesque and so

rich in color, that its architectural

defects

are

easily overlooked. The external

veneering of white and colored marble

occurs

rarely

in the East, but became a favorite

practice in Venice, where it

continued in use

for

five hundred years. The interior of

St. Mark's, in some respects

better preserved

than

that of Hagia Sophia, is especially

fine in color, though not equal in

scale and

grandeur

to the latter church. With its five

domes it has less unity of

effect than

Hagia

Sophia, but more of the charm of

picturesqueness, and its less

brilliant and

simpler

lighting enhances the impressiveness of

its more modest

dimensions.

FIG.

79.--INTERIOR OF ST.

MARK'S.

In

Russia and Greece the Byzantine

style has continued to be the

official style of the

Greek

Church. The Russian monuments

are for the most part of a somewhat

fantastic

aspect,

the Muscovite taste having

introduced many innovations in the form

of

bulbous

domes and other eccentric

details. In Greece there are

few large churches,

and

some of the most interesting,

like the Cathedral at Athens,

are almost toy-like

in

their

diminutiveness. On Mt.

Athos (Hagion

Oros) is an ancient monastery which

still

retains

its Byzantine character and

traditions. In Armenia (as at Ani,

Etchmiadzin,

etc.)

are also interesting

examples of late Armeno-Byzantine

architecture, showing

applications

to exterior carved detail of

elaborate interlaced ornament

looking like a

re-echo

of Celtic MSS. illumination,

itself, no doubt, originating in

Byzantine

traditions.

But the greatest and most prolific

offspring of Byzantine

architecture

appeared

after the fall of Constantinople (1453) in the new

mosque-architecture of

the

victorious Turks.

MONUMENTS.

CONSTANTINOPLE: St. Sergius, 520; Hagia

Sophia, 532538; Holy

Apostles

by Justinian (demolished); Holy Peace

(St. Irene) originally by

Constantine,

rebuilt

by Justinian, and again in 8th

century by Leo the Isaurian;

Hagia Theotokos, 12th

century

(?); Mon�tes Choras ("Kahir�

Djami"), 10th century; Pantokrator;

"Fetiyeh

Djami."

Cisterns, especially the "Bin

Bir Direk" (1,001 columns)

and "Yere Batan

Serai;"

palaces,

few vestiges except the

great hall of the Blachern�

palace. SALONICA: Churches--

of

Divine Wisdom ("Aya Sofia")

St. Bardias, St. Elias.

RAVENNA: San Vitale,

527540.

VENICE:

St. Mark's, 9771071; "Fondaco

dei Turchi," now Civic

Museum, 12th century.

Other

churches at Athens and Mt.

Athos; at Misitra, Myra,

Ancyra, Ephesus, etc.;

in

Armenia

at Ani, Dighour, Etchmiadzin,

Kouthais, Pitzounda, Usunlar,

etc.; tombs at Ani,

Varzhahan,

etc.; in Russia at Kieff

(St. Basil, Cathedral),

Kostroma, Moscow

(Assumption,

St.

Basil, Vasili Blaghennoi,

etc.), Novgorod, Tchernigoff; at

Kurtea Darghish in

Wallachia,

and

many other places.

17.

"St.

Sophia," the common name of

this church, is a misnomer. It

was not

dedicated

to a saint at all, but to the

Divine Wisdom (Hagia

Sophia), which name

the

Turks have retained in the

softened form "Aya

Sofia."

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.