|

EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA |

| << ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE |

| BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS >> |

CHAPTER

X.

EARLY

CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Bunsen, Die

Basiliken christlichen Roms.

Butler, Architecture

and

other Arts in Northern

Central Syria.

Corroyer, L'architecture

romane.

Cummings,

A

History of Architecture in

Italy.

Essenwein (Handbuch d. Architektur),

Ausg�nge

der

klassischen

Baukunst.

Gutensohn u. Knapp, Denkm�ler

der christlichen Religion.

H�bsch,

Monuments

de l'architecture chr�tienne.

Lanciani, Pagan

and Christian Rome.

Mothes,

Die

Basilikenform bei den

Christen,

etc. Okely, Development

of Christian

Architecture

in Italy. Von

Quast, Die

altchristlichen Bauwerke zu

Ravenna. De

Rossi,

Roma

Sotterranea. De

Vog��, Syrie

Centrale;

�glises

de la Terre Sainte.

INTRODUCTORY.

The

official recognition of Christianity in

the year 328 by

Constantine

simply legalized an institution which had

been for three

centuries

gathering

momentum for its final conquest of the

antique world. The new religion

rapidly

enlisted in its service for a

common purpose and under a common

impulse

races

as wide apart in blood and

culture as those which had built up the art

of

imperial

Rome. It was Christianity which

reduced to civilization in the West

the

Germanic

hordes that had overthrown Rome,

bringing their fresh and

hitherto

untamed

vigor to the task of recreating

architecture out of the decaying

fragments of

classic

art. So in the East its life-giving

influence awoke the slumbering

Greek art-

instinct

to new triumphs in the arts of building,

less refined and perfect

indeed, but

not

less sublime than those of the

Periclean age. Long before

the Constantinian edict,

the

Christians in the Eastern provinces had

enjoyed substantial freedom of

worship.

Meeting

often in the private basilicas of wealthy

converts, and finding these, and

still

more

the great public basilicas,

suited to the requirements of their

worship, they

early

began to build in imitation of these

edifices. There are many

remains of these

early

churches in northern Africa and central

Syria.

EARLY

CHRISTIAN ART IN ROME. This

was at first wholly sepulchral,

developing

in

the catacombs the symbols of the new faith.

Once liberated, however,

Christianity

appropriated

bodily for its public rites

the basilica-type and the general

substance of

Roman

architecture. Shafts and capitals,

architraves and rich linings of

veined

marble,

even the pagan Bacchic

symbolism of the vine, it adapted to new

uses in its

own

service. Constantine led the way in

architecture, endowing Bethlehem

and

Jerusalem

with splendid churches, and his new

capital on the Bosphorus with the

first

of the three historic basilicas

dedicated to the Holy Wisdom (Hagia

Sophia). One

of

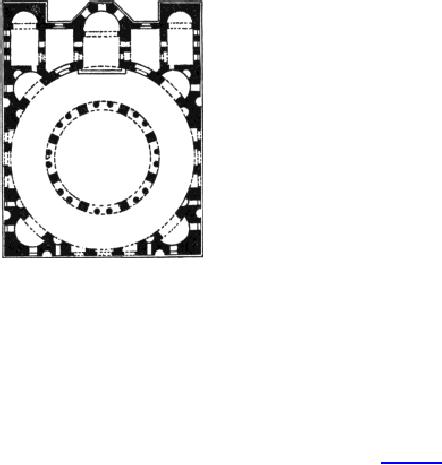

the greatest of innovators, he seems to

have had a special predilection for

circular

buildings,

and the tombs and baptisteries which he

erected in this form, especially

that

for his sister Constantia in

Rome (known as Santa Costanza,

Fig. 66), furnished

the

prototype for numberless Italian

baptisteries in later

ages.

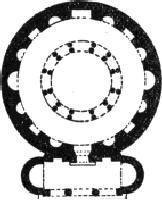

FIG.

66.--STA. COSTANZA, ROME.

The

Christian basilica (see

Figs. 67, 68) generally comprised a

broad and lofty nave,

separated

by rows of columns from the single or

double side-aisles. The aisles

had

usually

about half the width and height of the

nave, and like it were

covered with

wooden

roofs and ceilings. Above the

columns which flanked the nave

rose the lofty

clearstory

wall, pierced with windows above the

side-aisle roofs and supporting

the

immense

trusses of the roof of the nave. The

timbering of the latter was

sometimes

bare,

sometimes concealed by a richly panelled

ceiling, carved, gilded, and

painted.

At

the further end of the nave was the

sanctuary or apse, with the seats for

the

clergy

on a raised platform, the bema, in front of

which was the altar.

Transepts

sometimes

expanded to right and left before the

altar, under which was the confessio

or

shrine of the titular saint or

martyr.

An

atrium

or

forecourt surrounded by a covered

arcade preceded the basilica

proper,

the

arcade at the front of the church forming a

porch or narthex, which,

however, in

some

cases existed without the atrium. The

exterior was extremely

plain; the interior,

on

the contrary, was resplendent with

incrustations of veined marble and

with

sumptuous

decorations in glass mosaic

(called opus

Grecanicum) on a

blue or golden

ground.

Especially rich were the half-dome of the

apse and the wall-space

surrounding

its arch and called the

triumphal

arch; next in

decorative importance

came

the broad band of wall beneath the

clearstory windows. Upon these

surfaces

the

mosaic-workers wrought with minute cubes of

colored glass pictures and

symbols

almost

imperishable, in which the glow of color

and a certain decorative grandeur

of

effect

in the composition went far to atone for the uncouth

drawing. With growing

wealth

and an increasingly elaborate ritual, the furniture

and equipments of the

church

assumed greater architectural

importance. A large rectangular

space was

retained

for the choir in front of the bema, and

enclosed by a breast-high parapet

of

marble,

richly inlaid. On either side

were the pulpits or ambones

for the

Gospel and

Epistle.

A lofty canopy was built over the

altar, the baldaquin,

supported on four

marble

columns. A few basilicas were built with

side-aisles, in two stories, as in

S.

Lorenzo and Sta. Agnese.

Adjoining the basilica in the earlier

examples were the

baptistery

and the tomb of the saint, circular or

polygonal buildings usually; but

in

later

times these were replaced by

the font or baptismal chapel in the church and

the

confessio

under the

altar.

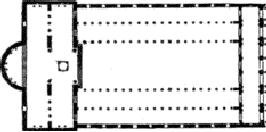

FIG.

67.--PLAN OF THE BASILICA OF

ST. PAUL.

Of

the two Constantinian basilicas in Rome,

the one dedicated to St.

Peter was

demolished

in the fifteenth century; that of

St.

John Lateran has

been so disfigured

by

modern alterations as to be

unrecognizable. The former of the two

adjoined the

site

of the martyrdom of St. Peter in the

circus of Caligula and Nero; it

was five-

aisled,

380 feet in length by 212 feet in width.

The nave was 80 feet wide

and 100

feet

high, and the disproportionately high

clearstory wall rested on

horizontal

architraves

carried by columns. The impressive

dimensions and simple plan of this

structure

gave it a majesty worthy of its rank as

the first church of Christendom.

St.

Paul

beyond the Walls (S.

Paolo fuori le mura), built in 386 by

Theodosius,

resembled

St. Peter's closely in plan

(Figs. 67, 68). Destroyed by fire in

1821, it has

been

rebuilt with almost its

pristine splendor, and is, next to the

modern St. Peter's

and

the Pantheon, the most impressive

place of worship in Rome.

Santa

Maria

its

original aspect, its

Renaissance ceiling happily

harmonizing with its

simple

antique

lines. Ionic columns support

architraves to carry the clearstory, as

in St.

Peter's.

In most other examples, St.

Paul's included, arches turned from

column to

column

perform this function. The first known

case of such use of classic

columns as

arch-bearers

was in the palace of Diocletian at

Spalato; it also appears in

Syrian

buildings

of the third and fourth centuries A.D.

The

basilica remained the model for

ecclesiastical architecture in Rome,

without

noticeable

change either of plan or detail, until

the time of the Renaissance. All

the

earlier

examples employed columns and

capitals taken from ancient

ruins, often

incongruous

and ill-matched in size and order.

San

Clemente (1084)

has retained

almost

intact its early aspect,

its choir-enclosure, baldaquin, and

ambones having

been

well preserved or carefully restored.

Other important basilicas are

mentioned in

the

list of monuments on pages 118,

119.

RAVENNA.

The fifth and

sixth centuries endowed

Ravenna with a number of notable

buildings

which, with the exception of the cathedral,

demolished in the last century,

have

been preserved to our day. Subdued by the

Byzantine emperor Justinian in

537,

Ravenna

became the meeting-ground for Early

Christian and Byzantine traditions

and

the

basilican and circular plans

are both represented. The two churches

dedicated to

St.

Apollinaris, S.

Apollinare Nuovo (520) in the

city, and S.

Apollinare in Classe

(538)

three miles distant from the city, in

what was formerly the port, are

especially

interesting

for their fine mosaics, and for the

impost-blocks interposed above

the

capitals

of their columns to receive the springing

of the pier-arches. These

blocks

appear

to be somewhat crude modifications of the

fragmentary architraves or

entablatures

employed in classic Roman

architecture to receive the springing

of

The

use of external arcading to

give some slight adornment

to the walls of the second

of

the above-named churches, and the round

bell-towers of brick which adjoined

both

of

them, were first steps

toward the development of the "wall-veil" or

arcaded

decoration,

and of the campaniles, which in later

centuries became so

characteristic

of

north Italian churches (see Chapter XIII.). In

Rome the campaniles which

accompany

many of the medi�val basilicas are

square and pierced with many

windows.

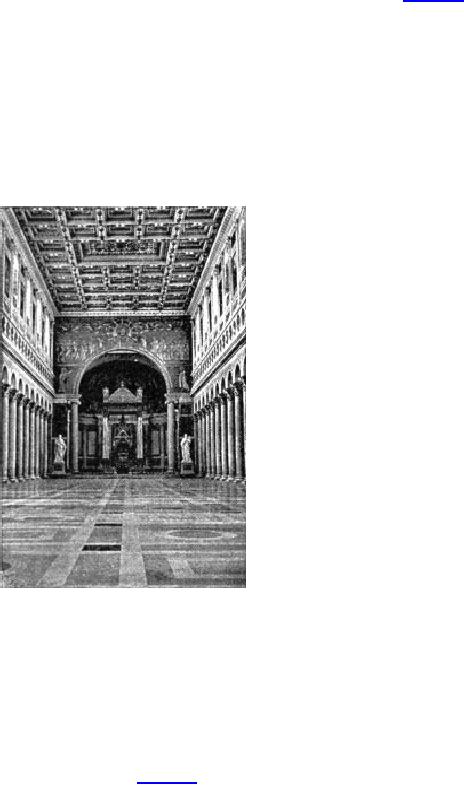

FIG.

68.--ST. PAUL BEYOND THE

WALLS. INTERIOR.

The

basilican form of church became general

in Italy, a large proportion of

whose

churches

continued to be built with wooden roofs

and with but slight deviations

from

the

original type, long after

the appearance of the Gothic style. The

chief departures

from

early precedent were in the

exterior, which was embellished with

marble

incrustations

as in S. Miniato (Florence); or with successive

stories of wall-arcades,

as

in many churches in Pisa and Lucca

(see Fig.

90);

until finally the introduction of

clustered

piers, pointed arches, and

vaulting, gradually transformed the

basilican into

the

Italian Romanesque and Gothic

styles.

SYRIA

AND THE EAST. In

Syria, particularly the central

portion, the Christian

architecture

of the 3d to 8th centuries produced a number of very

interesting

monuments.

The churches built by Constantine in

Syria--the Church of the Nativity

in

Bethlehem (nominally built by his

mother), of the Ascension at Jerusalem,

the

magnificent

octagonal church on the site of the

Temple, and finally the somewhat

similar

church at Antioch--were the most notable

Christian monuments in Syria.

The

first

three on the list, still

extant in part at least,

have been so altered by

later

additions

and restorations that their original

forms are only approximately

known

from

early descriptions. They were all of

large size, and the octagonal church on

the

marble

incrustations of the early design

are still visible in the

"Mosque of Omar,"

but

most of the old work is concealed by the

decoration of tiles applied by

the

Moslems,

and the whole interior aspect altered by

the wood-and-plaster dome with

which

they replaced the simpler roof of the

original.

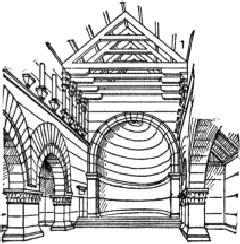

FIG.

69.--CHURCH AT KALB

LOUZEH.

Christian

architecture in Syria soon,

however, diverged from Roman

traditions. The

abundance

of hard stone, the total lack of

clay or brick, the remoteness from

Rome,

led

to a peculiar independence and

originality in the forms and details of

the

ecclesiastical

as well as of the domestic architecture of

central Syria. These

innovations

upon Roman models resulted in the

development of distinct types

which,

but

for the arrest of progress by the

Mohammedan conquest in the seventh

century,

would

doubtless have inaugurated a new and

independent style of architecture.

Piers

of

masonry came to replace the

classic column, as at Tafkha (third or fourth

century),

Rouheiha

and Kalb Louzeh (fifth century?

Fig. 69); the ceilings in the

smaller

churches

were often formed with stone

slabs; the apse was at first

confined within

the

main rectangle of the plan, and was

sometimes square. The exterior

assumed a

striking

and picturesque variety of forms by

means of turrets, porches, and

gables.

Singularly

enough, vaulting hardly appears at all,

though the arch is used with

fine

effect.

Conventional and monastic groups of

buildings appear early in

Syria, and that

of

St.

Simeon Stylites at

Kelat Seman is an impressive and

interesting monument.

Four

three-aisled wings form the arms of a

cross, meeting in a central

octagonal open

court,

in the midst of which stood the column of the

saint. The eastern arm of the

cross

forms a complete basilica of

itself, and the whole cross

measures 330 � 300

feet.

Chapels, cloisters, and cells

adjoin the main edifice.

FIG.

70.--CATHEDRAL AT BOZRAH.

Circular

and polygonal plans appear in a number of

Syrian examples of the

early

sixth

century. Their most striking

feature is the inscribing of the circle

or polygon in

a

square which forms the exterior

outline, and the use of four niches to

fill out the

corners.

This occurs at Kelat Seman in a

small double church, perhaps the tomb

and

chapel

of a martyr; in the cathedral at Bozrah

(Fig.

70), and in the small domical

church

of St.

George at

Ezra.

These were probably the

prototypes of many Byzantine

though

the exact dates of the Syrian

churches are not known. The one at

Ezra is the

only

one of the three which has a

dome, the others having been

roofed with wood.

The

interesting domestic architecture of

this period is preserved in whole towns

and

villages

in the Hauran, which, deserted at the Arab

conquest, have never

been

reoccupied

and remain almost intact but for the

decay of their wooden roofs.

They

are

marked by dignity and simplicity of

design, and by the same picturesque

massing

of

gables and roofs and porches which

has already been remarked of

the churches.

The

arches are broad, the

columns rather heavy, the

mouldings few and simple, and

the

scanty carving vigorous and

effective, often strongly

Byzantine in type.

Elsewhere

in the Eastern world are many early

churches of which even the

enumeration

would exceed the limits of this work.

Salonica counts a number of

basilicas

and several domical churches. The church

of St.

George, now a

mosque, is

of

early date and thoroughly

Roman in plan and section, of the same

class with the

Pantheon

and the tomb of Helena, in both of which a massive

circular wall is

lightened

by eight niches. At Angora

(Ancyra), Hierapolis, Pergamus, and

other

points

in Asia Minor; in Egypt, Nubia, and

Algiers, are many examples of

both

circular

and basilican edifices of the early

centuries of Christianity. In

Constantinople

there

remains but a single representative of

the basilican type, the church of

St.

John

Studius, now the

Emir Akhor mosque.

MONUMENTS:

ROME: 4th century: St. Peter's,

Sta. Costanza, 330?; Sta.

Pudentiana,

335

(rebuilt 1598); tomb of St.

Helena; Baptistery of Constantine;

St. Paul's beyond

the

Walls,

386; St. John Lateran

(wholly remodelled in modern

times). 5th century:

Baptistery

of St. John Lateran; Sta.

Sabina, 425; Sta. Maria

Maggiore, 432; S. Pietro in

Vincoli,

442 (greatly altered in modern

times). 6th century: S. Lorenzo, 580

(the older

portion

in two stories); SS. Cosmo e

Damiano. 7th century: Sta.

Agnese, 625; S. Giorgio

in

Velabro, 682. 8th century: Sta.

Maria in Cosmedin; S. Crisogono. 9th

century:

S.

Nereo ed Achilleo; Sta.

Prassede; Sta. Maria in

Dominica. 12th and 13th

centuries:

S.

Clemente, 1118; Sta. Maria in

Trastevere; S. Lorenzo (nave);

Sta. Maria in Ara

Coeli.

RAVENNA:

Baptistery of S. John, 400 (?); S.

Francesco; S. Giovanni Evangelista, 425;

Sta.

Agata,

430; S. Giovanni Battista, 439; tomb of

Galla Placidia, 450; S. Apollinare

Nuovo,

500520;

S. Apollinare in Classe, 538; St.

Victor; Sta. Maria in

Cosmedin (the Arian

Baptistery);

tomb of Theodoric (Sta.

Maria della Rotonda, a

decagonal two-storied

mausoleum,

with a low dome cut from a

single stone 36 feet in

diameter), 530540.

ITALY IN GENERAL:

basilica at Parenzo, 6th century;

cathedral and Sta. Fosca at

Torcello,

640700;

at Naples Sta. Restituta, 7th

century; others, mostly of

10th-13th centuries, at

Murano

near Venice, at Florence (S.

Miniato), Spoleto, Toscanella,

etc.; baptisteries at

Asti,

Florence, Nocera dei Pagani,

and other places. IN SYRIA AND THE

EAST:

basilicas of

the

Nativity at Bethlehem, of the

Sepulchre and of the

Ascension at Jerusalem;

also

polygonal

church on Temple platform;

these all of 4th century.

Basilicas at Bakouzah,

Hass,

Kelat Seman, Kalb Louzeh,

Rouheiha, Tourmanin, etc.;

circular churches,

tombs,

and

baptisteries at Bozrah, Ezra,

Hass, Kelat Seman, Rouheiha,

etc.; all these

4th-8th

centuries.

Churches at Constantinople (Holy

Wisdom, St. John Studius,

etc.), Hierapolis,

Pergamus,

and Thessalonica (St.

Demetrius, "Eski Djuma"); in

Egypt and Nubia

(Djemla,

Announa,

Ibreem, Siout, etc.); at

Orl�ansville in Algeria. (For

churches, etc., of

8th-10th

centuries

in the West, see Chapter

XIII.)

15.

Hereafter

the abbreviation S. M. will be generally

used instead of the

name

Santa

Maria.

16.

Fergusson

(History

of Architecture,

vol. ii., pp. 408, 432) contends that

this

was

the real Constantinian

church of the Holy Sepulchre,

and that the one

called

to-day

by that name was erected by

the Crusaders in the twelfth

century. The more

general

view is that the latter

was originally built by Constantine as

the Church of

the

Sepulchre, though subsequently

much altered, and that

the octagonal edifice

was

also his work, but erected

under some other name.

Whether this church

was

later

incorporated in the "Mosque of

Omar," or merely furnished

some of the

materials

for its construction, is not quite

clear.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.